Photos by former APF Fellow William Prochna

TUNICA, Mississippi – Nobody in Miss Mitchell’s Algebra I class learned much in 1993 because Miss Mitchell quit in October. No replacement could be found. The principal at Rosa Fort High School neglected to mention these facts to Miss Liimatta when she was hired the following year to teach Algebra II.

Miss Liimatta soon learned that the all-black public schools in the impoverished Upper Delta of Mississippi had great difficulty recruiting teachers. Rosa Fort rarely found substitute teachers, even for a day. After Miss Mitchell’s abrupt departure, her students had sat, more or less, unattended in the room at the end of the hall for the rest of the school year.

Janet Liimatta was at the time 21 years old. She was fresh out of college and had signed on with Teach For America to teach in the rural South. She had grown up in suburban Baltimore, the daughter of a community college instructor, and believed education to be, she said, “the great equalizer.”

Teach For America, the national organization that sends newly-minted college graduates into the poorest schools in the country, would give her a chance to prove the theory.

Miss Mitchell’s old class room was just beyond the stench of urine that wafted down the hall from the lavatories. There was no knob on the door. Inside the room, Liimatta found liquor bottles on the floor amid piles of trash, and food stains on the wall.

“I thought I would go there Day One and start Algebra II and they would be right there, ready to continue,” she says now with a laugh at her own naivete. “The only thing they had learned was that whenever they saw the letter X, that equaled one. When the answer was X equals seven, they would cross out the seven and write X equals one. No matter what the answer was, X equaled one. I stopped using the letter X.”

Liimatta’s three years in Tunica were a mixture of frustration and triumph. She met bright and gifted students who had overcome great odds. But she also met students from families so poor they didn’t know the difference between an area code and a Zip Code because no one at home had ever made a long distance call. She found herself teaching 10th grade math to students who could not multiply. More than a few of her students could not read. Once, a student came to her in a panic with an AIDS pamphlet he wanted deciphered because he couldn’t understand the word “nausea.”

While she taught at Rosa Fort, the class of 1996 became the first class in which every member passed the Mississippi Functional Literacy Exam, a state requirement for graduation, on the first attempt. The test is given in the spring of the junior year, so those who fail can have another chance at it in their senior year.

“You’re celebrating eleventh graders who are able to pass an eighth grade exam,” she said. “I wonder what it really means to have a diploma from Rosa Fort.”

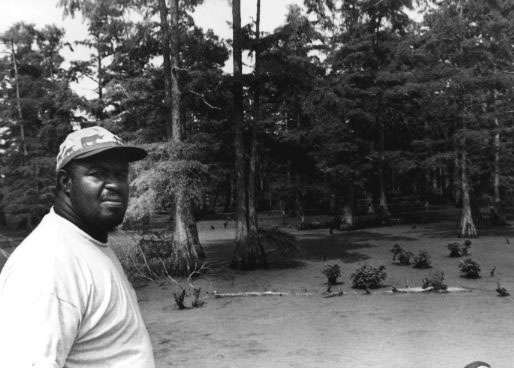

Tunica, the county seat of Tunica County, lies just 30 miles south of Memphis in the long, flat expanse of fertile alluvium soil along the Mississippi River where cotton still dominates and defines everyday life. Until recently, Tunica County was the poorest county in the country. Of the 8,400 people who live there, three-quarters of them are black and many still live in ragged shanties with tin roofs and warped cypress floors. The abysmal condition of its public schools seemed hardly typical of the problems in schools elsewhere. But it is more typical than appears at first glance. The problems Tunica faces can be found in any big school district: teenage pregnancy, a troublesome dropout rate, overworked and under-prepared teachers, disinterested and uninformed parents, and students who come to class without even a pencil.

“Tunica is its own little inner city,” Liimatta said. “Right in the middle of nowhere.”

Tunica also provides a stunning example of how integration hasn’t worked and how it has perpetuated one of the most troublesome problems in the country today: illiteracy. Indeed, Tunica County’s high illiteracy rate is a direct result of the failure of its public schools to both keep students enrolled and educate them by the time they graduate.

Today, Tunica County is undergoing great upheaval. Ten new Las Vegas-style casinos, built in the midst of the cotton fields in the last four years as a result of Mississippi’s new local option gaming laws, attract more than one million visitors a month and keep Tunica rich with new tax revenues. Some of the money has gone to the schools: Rosa Fort High School dedicated a new $1 million library and science lab complex in October and there are plans to fully renovate the district’s rundown class room buildings and build a new elementary school. This fall, the high school began teaching foreign languages – a basic college entrance requirement – and there are plans to publish a yearbook for the first time in a dozen years. But the problems of Tunica’s schools are so entrenched, it will take more than new tax dollars and more than a few years to correct them, and neither blacks nor whites here are sure how to proceed. Rosa Fort’s new principal, Dorsey Patterson, emphasizes “structure and discipline,” but his teachers are skeptical.

The Legacy of Plantation Schools

“Will the schools become better? Surely it will happen,” said Dr. Sara Schrader, until recently Tunica’s lone physician. “I don’t have any idea how. I can’t envision the force that will make it happen.”

The decline of the public schools in Tunica is a long, sad story, rooted in Tunica’s plantation lifestyle and its racial separatism. Tunica is a tiny white island in a majority black county. Its population is just over 1,200 and its boundaries exclude most black residents. Although the county is three-quarters black, the town is three-quarters white. The county and the town operate as two distinct worlds, even though one is part of the other.

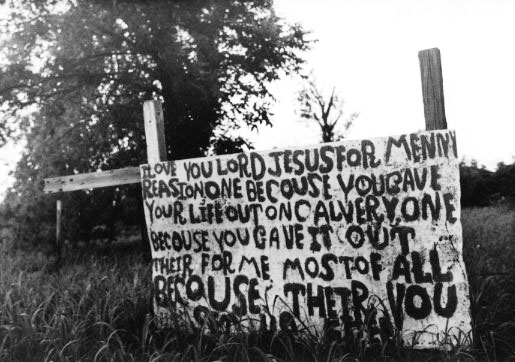

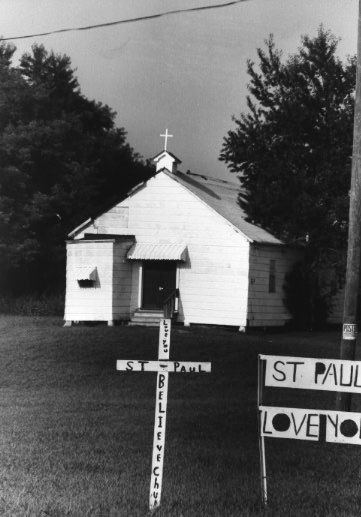

White planters in the Delta believed that educating black field laborers would lead to trouble: the workers would become dissatisfied with their lot in life, quit or rebel. Statistics tell the story. In 1954, the year the Supreme Court handed down its historic Brown v. the Board of Education decision that rejected the doctrines of separate but equal schools, one in four white children in Mississippi graduated from high school, according to a report filed with the legislature. The figure for black children was one in 40. In Tunica County, there were 2,792 black children enrolled in school that year – although unusual schools they were – and only 10 of them were in the twelfth grade. In Tunica, like elsewhere in the Delta, black children attended plantation schools until the early 1960s. The schools were run by the school district, but located on plantations, often in small, one-room churches. They operated six months a year.

When Edna Carpenter began teaching in 1953, Tunica County had 44 plantation schools. Black teachers were not required to be college graduates, although Carpenter had a bachelor’s degree. They got paid every 20 days. Sometimes the August paycheck was held up until November because the schools closed in mid-month while the students and teachers went out to the field to pick cotton. They reopened again when the crop was in. On payday, when the black teachers gathered at the courthouse to collect their checks, the white officials asked them to sing Negro spirituals before the checks were handed out. To the whites, these little impromptu concerts were evidence of the good will between the races because they showed how much the whites were interested in “their” blacks and their music. The blacks didn’t see it that way.

“We saw it as having to sing for our paychecks,” Carpenter said. “‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’ was their favorite and we hated it.”

Many of Tunica’s teachers today began their education in the plantation schools. Earl Dishmon, now Rosa Fort’s vice principal, was among them. “You’d get out of school in time to be in the fields by one o’clock,” he said.

Integration was the turning point. When the whites opted out of the school system rather than integrate, they set the public school system on an inevitable course toward the kind of ruin that Janet Liimatta would encounter in 1994.

Integration was so adamantly opposed in Mississippi that two years after the Brown decision, voters approved a constitutional amendment granting the legislature authority to abolish Mississippi’s public schools. The legislature declined to take such a drastic step and instead devised ways to avoid integration until the federal courts finally prevailed in the late 1960s.

In Tunica, the showdown came at Christmas in 1969. By that time, the plantation schools had been consolidated into the Tunica County Colored High School – later renamed Rosa Fort – just outside the town boundary, and one elementary school in the south end of the county. About 3,000 black students were enrolled in both schools. The 430 white children in the district attended the neat, red-brick schools on School Street in Tunica. Faced with merging “two distinct, historic cultures,” as Bobby Papasan, the white superintendent later put it, the whites withdrew en masse. Nineteen of the 25 teachers who taught in the white public schools went with them. The new, all-white private academy was too small to absorb so many new students at once, so the teachers taught the white children in Tunica’s churches, using the school district’s text books.

Miriam Tyler was a senior at the white Tunica County High School during that memorable Christmas break. “They called us into a big meeting and told us the school was going to be closed down,” she said. “I graduated from the Baptist Church.” Her diploma has never been signed. The white schools stood empty for a long time after that winter, so long that the roof of the elementary school fell in and the library books rotted. Across Highway 61, at Rosa Fort, the black students returned to class after the Christmas break and uneasily watched the developments unfold. “We didn’t figure they were going to go to church,” said Joe Eddie Hawkins, who graduated in 1971. “But we didn’t figure they were going to come with us either. We were still going in the back door of the café and upstairs in the movie theater.”

The school board continued to pay the 19 white teachers who fled to the churches, although in the summer of 1970 yet another federal court decree ordered the teachers to reimburse the school district and return the district’s books. The school board also initially refused to reassign the six white teachers who stayed on the job to their new black students until Patty Sue Tucker, who taught elementary school music, threatened to go to the newspaper in Memphis. Tunica was never the same.

“We had an all-white school board and a white superintendent,” Tucker said. “Their enthusiasm for the schools declined immediately.” Papasan, who was appointed superintendent in 1970 and remained until 1988, worked to reduce the high dropout rate and expand the curriculum. But he sent his own children to the all-white private academy, Tunica Institute of Learning, and was deeply distrusted by the black community he served. (Poor white children who couldn’t afford the institute’s tuition simply dropped out of school in the winter of 1970. Some moved away, some disappeared.)

Still Separate and Unequal

By the time blacks gained control of the school board and the superintendent’s post in the late 1980s, the decline was complete, and the schools in Tunica were as separate as they had been in the 1950s. There is no exchange between the two systems. Every fall, Tunica is host to two separate homecoming celebrations, one black, one white.

Black school leadership has also fared little better than white. The district is still ranked eighth from the bottom among Mississippi’s 153 school districts and, because of its low test scores, remains on academic probation.

“We need to start electing people who can turn our school system around,” Hawkins said. “When we had Europeans on the school board, our kids couldn’t read. We have African Americans on the board and an African American superintendent and our kids still can barely read or write.”

Ironically, casino gambling seems likely to have a greater impact on Tunica than all the desegregation plans combined. Gambling has created a boom in a dying town and brought all the festering indignities and suspicions to a head. The casino owners have not forced the issues out of any noble intent. They merely want a literate work force and good public schools for their employees’ kids.

Now the white planters in Tunica have a choice. Are they going to opt out, as they did the first time, to preserve separate societies? To do so might doom their town to wither, while the casino boom builds shopping malls and housing developments elsewhere.

“It doesn’t take a genius to figure out why people aren’t moving here,” said Greg Hurley, the assistant county administrator. “They don’t have anywhere to send their kids to school. People who didn’t grow up here have a problem sending their kids to a private school based on race.” Earl Yanase, general manager of the Grand Casino, which opened in June, says he is eager to provide scholarships or sponsor individual teachers or new programs. But he is loathe to delve too deeply into Tunica’s murky racial politics. That, he says, he will leave to the locals. It’s a practical decision, but not one that lends itself to optimism. Tunica’s history resonates with hard positions held.

Lynn Sturgill, a member of Tunica’s board of aldermen, has taught in both the public and private schools. A few years ago, several of her eighth grade students in the public junior high school asked if they could go to the private academy to watch the baseball practice. “I said I wish you could. They really have some good talent,” Sturgill said. “And they said, ‘You know, Miss Sturgill, we really don’t understand why we couldn’t play a game against them. It’d be fun. We read about them in the paper all the time and they read about us.’ And I said that would probably be one of the greatest things for Tunica County that could ever happen.” Sturgill said she mentioned the conversation to the coaches at both schools. Nothing happened.

©1997 Laura Parker

Laura Parker, a national correspondent for the Detroit News, is researching America’s illiteracy problem as it exists in Tunica, Mississippi.