TUNICA, MS. June, 1996 – A teacher stands before a blackboard in an otherwise barren room. Eleven faces stare back passively. Most are in their twenties, a few in their forties. They are newly hired cashiers at the Sheraton Casino. On Monday, they start work. They are gathered to bone up on decimals, since they will be dealing with dollars and cents. Sounded like a good idea, but after 30 minutes, the teacher has increasing doubts. She wants them to work problems containing decimals, but they are having trouble doing simple math. She bites into the silence that has enveloped the room. “Okay. What’s five times five?” No one says a word. The teacher turns to a woman who has come with her 21-year-old son. “Charlotte?” she asks. Charlotte hesitates. “Ten?”

The Tunica County Literacy Center is housed in a small, green corrugated metal building, the last structure on the black-topped road before the outer reaches of this small town in the Mississippi Delta give way to cotton fields and catfish ponds.

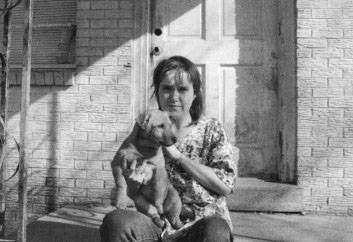

It is run by an energetic, 59-year-old woman who is relentlessly cheerful, optimistic, and persistent. She arrives every day just after dawn and stays until dusk. Inside, the work goes slowly. Hers is an occupation that does not bode for instant results. Victories are achieved in increments, sometimes imperceptible. She’s never sure where each lesson will lead.

“With a new group, I try to figure out where they’re coming from,” said Betty Jo Dulaney, who founded the center in 1985. She knows that some students may not be following the correct images in their brains, that their thought patterns are sometimes jumbled. Take math.

“If it’s not clicking, it’s because they’re adding instead of multiplying. That shows me they don’t listen to directions. Sometimes I have to teach a lesson in how to follow directions first,” she said.

Illiteracy in Tunica County was never, until recently, a cause for much concern. It was shunted off to the fringes, like the literacy center itself, even as the numbers loomed large – 50 percent of adults, Dulaney estimates, fed by poor schools, teen pregnancy, poverty, racial division, complacency.

“Tunica has always been unique in the attitudes toward education,” Dulaney said. “They didn’t see the need.”

There are only eight regulars enrolled, all women. They range in age from 17 to 62, but Dulaney never knows exactly who is going to show up. The group expands or contracts with no particular rhythm, depending on the condition of Lillie’s gout or the health of Bertha’s twins. Dulaney also serves innumerable drop-ins who come for varying lengths of time: people who’ve quit the catfish processing plant, workers from the bedding factory who want promotions, grandmothers who want to read their Bible, tractor drivers, welfare moms, and now, dozens of people who aspire to jobs at the glittering new casinos, which, improbably, have been built in the county along the edge of the Mississippi River and, just as improbably, have created 14,000 jobs in a county of 8,400 souls.

“Okay, we’re looking at ‘People’ today,” Dulaney says to the regulars. Today, they are five. They are gathered on folding metal chairs around a long metal table with Dulaney seated in the center. Each has a copy of People magazine, open to the table of contents. “There’s a story in here about an actress I want you to look at. She quit acting to compete in judo at the Olympics. Jodie, I want you to read the first three paragraphs. Then Lillie, you pick it up, then Bertha. Right here, Page 97. See? The actress had to set a goal. I want us to imagine getting our GEDs as our goal.”

Adult literacy was such a foreign concept to this town that when the Rotary Club decided to offer classes, a few years before Dulaney plunged in, it didn’t know how to find the people it aimed to teach. The Rotarians posted notices in the public library. Nobody came. The reason was simple in its logic; people who don’t read tend not to go to the library. But the Rotarians considered the lack of response not a failure on their part to communicate, but as proof that everybody who wanted to know how to read already knew.

Tunica County is like that, oddly disconnected. Until the legislature legalized gambling in 1990 and the casinos rushed in, Tunica it was isolated in its own self-spun cocoon. It was just 30 miles south of Memphis, yet there were people who lived there who had never seen a city bus or made a long distant telephone call. Three-quarters of the population was black, yet the county was dominated politically and economically by a few dozen white planters. The planters owned most of the land – they deal in cotton, soybeans and rice – and managed to hang onto an almost antebellum way of life that had long since disappeared from the rest of the South. The attitudes about race came right out of the 1930s.

When Dulaney began tutoring in 1985, she had better luck than the Rotarians. She drove out into the country and went into the black churches and onto the plantations. She signed up dozens of people for literacy class. She also ran up against what she so politicly describes as those “unique attitudes.”

She was called a “n…..” lover. She received harassing telephone calls at midnight from heavy breathers. There were snubs at church. When she ignored these “hints,” her students’ work schedules were changed so they would be unable to attend class.

“I was told they knew all they needed to know,” she said. “Empowerment has always been kind of frightening to everyone around here.”

The literacy center’s address was established during this phase. Dulaney wanted to open the center in town, near the county courthouse, but Tunica rebelled.

“This place wasn’t our first choice,” she said of her green metal building, as a crop duster buzzes overhead. “But people went to the town board and complained about me. I was told I would attract – quote, unquote – the wrong kind of people.”

If there was irony in this, it was that Dulaney came right out of the white power structure. A native of Philadelphia and daughter of a Naval officer, Dulaney married into a prominent Tunica family of lawyers which has served as attorneys to the local governing boards for three generations and has helped maintain the status quo. Her husband, William, is lawyer to the town of Tunica. William’s older brother, John, was lawyer to the school district and the county Board of Supervisors. John has since retired and William and Betty Jo’s son, Andy, has taken up the family business of tending to the county’s affairs.

She does not invite examination into the complexities of her family. She met her husband while she was in high school and he in the Navy. By 1958, a year after she graduated from the Philadelphia High School for Girls, she was married and living with her new in-laws while her new husband was away at sea. There were few women her age in Tunica. Her “salvation,” as she puts it, was college. She commuted to Memphis State, now the University of Memphis, and majored in history and psychology, with a minor in math, German and biology.

“My husband planned my courses,” she said. “I graduated with exactly the number of courses necessary. I didn’t want to do all that math, but William said it was good for my brain.”

The university sent her grades to her husband, the custom at the time. “You had to be 21, or everything came to your husband,” she said.

She adjusted to the ways of her new hometown, raised six children, found her niche. After 38 years, she is expert in avoidance. When confronted by prickly issues, she simply changes the subject. So how is it that she came to do literacy, working virtually alone?

“I’m just known as the person with causes,” she explains cheerfully. “Somebody had to do this.”

Judy Williams, who runs the Mississippi Governor’s Office of Literacy, noted that in all Dulaney’s years of struggle to build a literacy program, Dulaney has never mentioned the issue of race as one of the obstacles to her success.

A bolder person would have made a larger impact. But such a person would not have lasted in Tunica as a literacy tutor for 10 years.

Dulaney herself is full of contradictions. Despite her artful dodges, she is drawn to hot spots. Last fall, she ran for the school board, the first white to run in years, and by doing so, brought to the surface all the silent, repressed emotions about race that continually course through Tunica’s veins. Among the leaders in black Tunica, she was the candidate not to be trusted; she was a Dulaney, and everyone knows what the lawyers Dulaney represented. In white Tunica, she was the do-gooder friend taking up another useless cause. Nobody in white Tunica expected Dulaney’s literacy program to churn out students who would rise to high enough to become a threat. Likewise, nobody expected her to pull Tunica’s schools, which are on academic probation, back from the brink.

Dulaney herself glided along above the roil, leaving the particulars of the campaign to her husband and her son.

She won. She took all the white votes. Ten years of tutoring gave her the edge in black votes.

Isolated and poor in the Delta, Dulaney’s regulars at the literacy center seem an anomaly. They’re not. Her students are part of a huge pool of Americans, estimated by the U.S. Education Department at 90 million adults, whose literacy skills are so low, they are considered “at risk” in today’s society. A surprising number in these millions, as many as a fifth, have advanced as far as high school. They can manage basic tasks, but cannot synthesize more complicated endeavors, such as writing a short letter of complaint about a billing error or interpreting written jury instructions. They also told the researchers who conducted the federal study that they consider themselves literate.

Dulaney’s group reflects the findings. Bertha Walls, now 31 and the mother of twin girls, advanced to the 11th grade before she dropped out. She considers herself neither illiterate nor unique. All of her friends quit school. Some people she knows who graduated read worse than she does. At the other end of the spectrum is Anne Herring, who at 62, is the oldest of Dulaney’s students. She had little formal education, but has the most ambitious goals – to become a licensed practical nurse.

In reading People magazine, Dulaney’s students stumble over the words “initially,” “audition,” “independent.” Lillie Jones, 38, confuses “earnings” for “earrings.” She has the fine, elegant handwriting of a well-educated person, even though she quit school at 12 to chop cotton. Lillie also confuses several other words, raising other questions for Dulaney. Does Lillie have dyslexia? How long has it been since her last eye exam?

Bertha reads quickly, without punctuation. When she trips up on “priorities,” Dulaney intervenes. “Okay. Let’s look at a couple of words here. ‘Priorities.’ How would you define it?”

Bertha thinks for a moment. “It means he has his own thing, she has her own thing.”

Dulaney has used People magazine for reading class for some years. The stories are short, uncomplicated and more relevant to adults than some of the workbook lessons that come with literacy tutorial materials she gets by mail from New York. In this particular issue, the regulars are caught up by the cover story about a Hollywood baby boom. Madonna’s, Rosie O’Donnell’s. Bertha, who was recently married for the first time, is heartened. Her new husband wants a baby, but Bertha’s classmates think such a step premature so early in the marriage. Better to stay “unpregnant,” Lillie says. “Stay out of the bed,” Jodie suggests.

Dulaney’s involvement in literacy began in 1985 when Tunica was in the throes of another dose of national bad publicity about its poverty – in this instance, the issue concerned people living along an open sewer known as Sugar Ditch in a row of small shanties that lacked even the most basic plumbing. The Ditch, was it is known locally, was two blocks from downtown Tunica, right behind the Baptist Church, and the town aldermen had just spent a $500,000 federal grant refurbishing storefronts and constructing a new town plaza. The shacks on Sugar Ditch were not touched. The juxtaposition between the beautification project and a string of roach-infested shacks was irresistible to CBS’ “Sixty Minutes.” The broadcast featured a resident of the Ditch peeling back the wallpaper to reveal a wall black with roaches. Soon after the Rev. Jesse Jackson showed up and added his own memorable line to the lexicon of the Delta. “Tunica,” he declared, “is America’s Ethiopia.”

“I had been doing a lot of public speaking around the state at the time, pushing for reform of the public school system,” Dulaney said. “And then Sugar Ditch popped up. I saw I didn’t need to go elsewhere. When I first started tutoring, my headquarters was my car.”

In the black churches, Dulaney found elderly women who wanted to read their Bibles. She mothers to read to their children. She ran across two preachers who had memorized Bible verses so skillfully that not one member of either congregation knew of their limitations. She also taught the county sheriff’s mother to read, then – discreetly, at night after work – she tutored one of his deputies so he could get his GED.

Uneducated whites were fewer in number and more reluctant, especially men. “It’s very hard to teach those people,” Dulaney said. “Most of them have a chip on their shoulder.”

Nevertheless, she found them at her classes, too, including one man who could not identify his Social Security card as she fished it out of his wallet.

She was struck by his trust, although they had not met before. “I remember thinking to myself: how vulnerable these people are,” she said.

To watch Dulaney try to save Tunica one person at a time is to gain a fuller appreciation for the futility of the task. It is like trying to watch her dip the Mississippi dry with a teaspoon. After 10 years, fewer than 100 students have gone on to earn their GED. There are two schools of thought about this. The first involves the standard conspiracy theories about race; that the black community does not fully support her and the white community would not want a larger program to thrive if it truly empowered blacks.

The second scenario deals with more tangible issues, and through them, one can glimpse her devotion to her cause. Dulaney teaches mostly the poor, whose skills are so low when they begin she aims for more realistic goals: How to read a menu. How to find expiration dates on food at the Piggly Wiggly. How to make a long-distance telephone call.

“You don’t equate fire prevention with literacy,” she said. “But it’s important to be able to read EXIT and ALARM and what to do in case of a fire. We had four students whose homes burned, and in one fire, the mother and two of her children burned up.”

A range of factors work against her – in literacy, everything tends to work against you – time, funding, transportation, health care, childcare. Her program is linked to the community college system, which in Mississippi provides the foundation for most adult education programs. But the nearest campus is 25 miles away, and since many of her students don’t have cars, it might as well be a continent away.

She has trouble recruiting volunteers. Her students are beset not only by the usual pitfalls, but also by disastrous events, which occur with such regularity that they seem freakishly routine. They don’t suffer simple ailments; they get heart worm and pneumonia. Somebody is always missing class to midwife a baby. One woman student who showed promise, had to give up completely to tend for a young son who eventually died from a brain tumor. Another student had to drop out to search for a new house – in a county that has no houses to spare – after a tornado ripped away her roof. One of Dulaney’s regulars, Jodie Manues, who is white, dropped out of the private academy as a child after an especially wrenching trauma: her mother was shot dead in a downtown store and her father was charged with, then acquitted of, having hired a hit man to kill her.

Almost all of Dulaney’s regulars are going for their GEDs, an ordeal that to Dulaney sometimes seems more like watching Sisyphus roll his rock up the hill. By the end of last year, only Jodie had succeeded. Annie needed to complete the math and writing portions of the exam. Lillie had not passed science. After the first of the year, the state of Mississippi changed the minimum requirements for passing the exam, which means that the women will have to start all over again. And, so it goes.

Dulaney has always known it would take something extraordinary, something she could not imagine to convince Tunica that education was key to a shrinking farm town’s survival. She wondered over the years, as she worked alone in her green metal building, what could be extraordinary enough. The casinos, it seems have provided the answer, or at least a partial one. They have validated Dulaney’s point as she alone could not – that education makes a difference. The casinos provided 14,000 jobs, so many that anyone in Tunica County who wants one can have one. Trouble is, not everyone is qualified.

The teacher stands before her students and plods on. She points to the little, tiny dot on the blackboard, the all-important decimal. Do they get it? Do these new cashiers realize its significance? “Okay. What are you gonna do if you’re adding?” Silence. “You gotta line ’em up. What do I do to subtract?” No one wants to speculate. “You gotta line ’em up.” She points to a set of numbers, purposely askew. “Could I do this?” More silence. A man in a black baseball cap volunteers, “No, you can’t do that.” Ah! Finally, someone gets it. She rushes on, pointing to decimal. “Is it bad to forget that?” The man says, “Yes, very bad.” She turns to the others. Are they with her? “Do you want to do that, especially with other people’s money?”

©1997 Laura Parker

Laura Parker, a writer for USA TODAY on leave during her Patterson year, was a reporter on the national desk of The Washington Post and later an editor and writer for National Geographic, covering climate change and water issues.