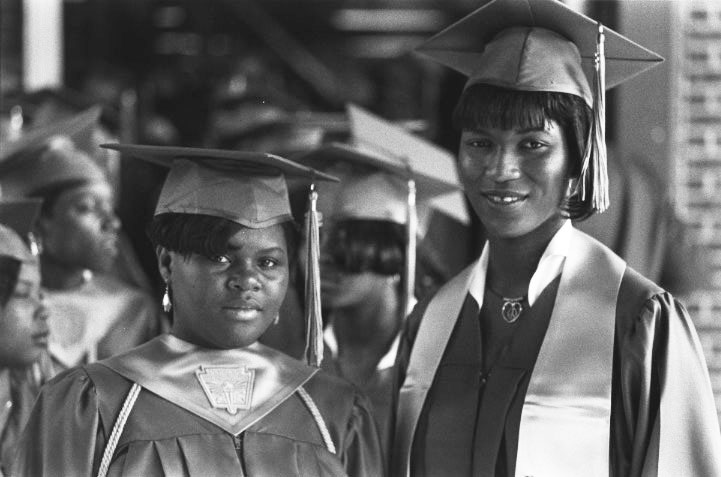

TUNICA, Miss. – Graduation at Rosa Fort High School here is one of the biggest social occasions of the year. It is usually held on the last Sunday in May, and this year, the Class of ’96 went forth at precisely 5 p.m., marching two-by-two into the gym and across the stage.

In years past, the graduates marched back out of the gym, took off their caps and gowns in the parking lot, turned onto Highway 61, the main route out of the impoverished Upper Mississippi Delta, and headed out of town.

“On graduation day, your brother or your sister or your uncle would come down from Chicago or Detroit, and as soon as graduation was over, you’d be loaded up to head north,” said Joe Eddie Hawkins, who graduated in 1971. “A lot of them left right from the campus.

They held the ceremony early enough in the day so you could get started before dark.”

Hawkins, now 43, moved slower than his classmates. He waited four days and joined the Marines – at the height of the Vietnam War.

“Even Vietnam looked better than Tunica,” he said.

Hawkins hopes those days will soon be behind Tunica for good. Long known as the poorest place in America, Tunica County bet its future in 1992 on casino gambling, and so far, has beat the odds. Ten casinos, clustered along the banks of the Mississippi River, now operate in the county, and they have spawned hotels, restaurants, and stores, with the promise of more to come.

The county coffers are awash with new tax dollars, enough to have constructed a new City Hall in Tunica, paved most of the county’s 500 miles of roads, built playfields and a baseball park in the black neighborhoods, and given all the teachers a $2,000 a year raise.

But in crucial ways, the opportunities remain just as elusive now as they were before, when all anyone in Hawkins’ graduating class could hope for was a job at the catfish processing plant for minimum wage, or an opening at the pillow factory, where the pay was not much more.

Chief among the reasons is Tunica’s extraordinarily high illiteracy rate. More than half the adults in Tunica County are functionally illiterate, meaning that, at best, they can read and write minimally, but not well enough to interpret a bus schedule, comprehend written jury instructions or write a short letter. That single factor has kept Tunica County from reaping a fuller benefit from its newfound wealth.

Most glaring is its unemployment rate: although Tunica County has more jobs than residents, its unemployment rate hovers around 13 percent – almost as high as it was before the casinos arrived. When the Grand Casino, the third largest in the country, opened in June, it created 3,600 new jobs. But most of the staff was hired from Memphis.

“Most of our folks read below the fourth grade level,” said Betty Jo Dulaney, who runs the Tunica County Literacy Council. “It is very difficult to bring those skills up. It’s not impossible, but it’s difficult.”

Illiteracy is so entrenched, so much a part of daily life that most people ignore it. It is rarely acknowledged as the reason for the oddly circuitous ways that groceries are bought, cars sold, prescriptions filled, and business deals made. Both the methods and the attitude are left over from the old plantation era, explained Sister Gus Griffin, a nun at the Catholic Social Services, who teaches reading to welfare moms. “If you kept them uneducated, you kept a cheap work force,” she said.

Rather than educate its population, Tunica adapted. Even today, the tellers at Planter’s Bank keep a special rubber stamp for customers who sign with an X. The bosses at Pride of the Pond catfish processing plant fill out all the necessary application and tax forms for their employees.

“If you live in Tunica County,” said Dr. Sara Schrader, who for a time was Tunica’s only physician, “the person selling you a car will take care of the paperwork. The pharmacist understands. The checker at the Piggly Wiggly knows.”

At the Tunica County Courthouse, Circuit Clerk Sharon Grandberry long ago gave up mailing out written summons for jury duty. Now, about three weeks before a new grand jury is convened, a deputy sheriff makes the rounds, personally contacting each of the 200 potential jurors in the pool.

The entire county operates on several different levels. The uneducated rely heavily on oral communication – as much as half the driving population takes an oral drivers license exam instead of a written one.

“For most of my students, their listening comprehension is very high,” said Maggie Guntren, who taught reading at Rosa Fort. “They are auditory learners.”

Illiteracy is not exclusively a black problem in Tunica, but it is most visible in the black neighborhoods, and it has helped maintain the racial divide. The gulf between the races is almost total. There are two sets of schools in Tunica County, the all-black public schools, which includes Rosa Fort, and the all-white private academy, the Tunica Institute of Learning, set up as a rebellion against federal orders to integrate the schools. There are two Little

Leagues and two swimming pools. Blacks swim in the public pool and whites swim in the private pool. No blacks belong to the Rotary Club, and, with very few exceptions, the only time a white person goes to a black church is when running for office.

Tunica is a small county – it counted 8,164 residents in the 1990 census, and most of them are black. The white population, however, lives in the town of Tunica, the county seat. The town boundaries were drawn in such a way to make Tunica an island, separated from the blacks, who live just outside the borders.

Until the 1980s, whites held all the elective offices. Now all five members of the school board are black, as is the county sheriff and the school superintendent, which in this county is also an elective post.

But whites have retained control over the most powerful body – the five-member Board of Supervisors, and Grandberry, who also oversees county elections, blames illiteracy, at least in part, for the black population’s inability to gain full control despite their overwhelming numbers.

In nearly every election, Grandberry said, she must discard dozens of ballots improperly filled out by voters who cannot read the ballot instructions. Some of the elections have been decided by as few as 16 votes.

“We’ve even talked about giving training sessions for voting,” Grandberry said. “But people with just a small amount of education don’t understand. I’ve had some ballots turned in where every box in the race has been checked.”

Illiteracy is rampant in the public schools; the school district has been on academic probation for seven of the last eight years. The casino money has helped some. Rosa Fort built a new computer lab two years ago, and is building a new library and chemistry labs scheduled to open this fall. But a few millions infused into the system don’t begin to address the most fundamental problems of a district that has been chronically under-funded and inadequately staffed. The administration has difficulty hiring and keeping good staff – Rosa Fort has had six principals in four years – and teachers struggle to teach students whose parents can’t read or write.

“There are not many books or magazines at home,” Guntren said. “No one is reading. Kids don’t see people reading.”

Sherrie Johnson, the senior class president and one of Rosa Fort’s top students, worries about how far behind she’ll be this fall in college. “That first year is going to be hard,” she said. “But we don’t have no other choice.”

John Learned, a casino executive brought in from Reno in 1992, had to redesign training programs for workers at Tunica’s first casino, Splash. Some of the employees had reached their 30th birthday without ever holding a job.

“It’s a tough labor force,” Learned said. “The managers here didn’t understand it. They would tell me, ‘I can’t get these people to work.’ Only later did he discover that the problem was employees had been given written instructions.

“You can’t put a memo on the board and expect your employees to read it if your employees don’t know how to read,” he said.

The Tunica Literacy Council, founded a decade ago, methodically tries to recover Rosa Fort’s dropouts. Dulaney, who comes from one of Tunica’s most prominent white families, had to overcome resistance in the white community before convincing the county supervisors to fund her program. The job is painfully tedious, the progress slow. The students have many more distractions now – children to raise, households to run. Some of the students in Dulaney’s current class have been working toward their high school equivalency exams for longer than they would have attended Rosa Fort the first time through.

Dulaney is fortified by her success stories. This spring, Annie Herring, mother of 15 and well into her 60s before she took up where she left off in school, was named Mississippi’s literacy student of the year. But in many ways, Dulaney has an impossible job. Tunica’s problem is too big for her.

The obvious next step is to improve the schools. The casinos are pushing for it, as are the students.

“Our standards aren’t high enough,” said Johnson, who wants to go to college and then into real estate development.

Annette Conley, the valedictorian for the Class of 96, just shakes her head. “Just look at this school,” she said the day after graduation, decrying the lack of academic experiences. “They (teachers) throw them (students) anything. Here they need art class. They need (academic) clubs.”

On graduation day, Conley was awarded a four-year scholarship from Harrah’s casino. She intends to use it to study pre-med at Howard University in Washington, D.C. She’d like to come back to Tunica after college. But she has her doubts about the wisdom of such a return.

“I’m not gonna try to come back and be Superwoman,” she said. “Tunica needs too much to be perfected. If I came back and built a hospital and a daycare center, that’s just one little piece of the puzzle. Now who’s gonna add the other pieces?”

©1996 Laura Parker

Laura Parker, a reporter in the Washington bureau of the Detroit News, is examining illiteracy in America through the experience of Tunica, Mississippi.