Tel Aviv, Israel

December, 1971

Under a warm winter sun, Bedouin tribesmen in layered dark flowing robes, with long curved knives dangling from their belts, hurry about their business in the busy streets of the old town of Beersheva, the gateway to the Negev desert, much as generations of their forebearers have done before them. In this modern day, the Bedouins, who still come to town leading caravans of camels to the early morning market, cross paths with bankers, shopkeepers, college students, desert scientists, ever-increasing numbers of tourists, and ubiquitous uniformed Israeli soldiers, the young women in distractingly short olive green skirts and the young men carrying their automatic rifles as casually as the Bedouins wear their knives, setting the guns down on snack bar counters as one might an umbrella. Despite the souvenir shops, travel agencies, banks, offices and department stores crowded into its small buildings, the old town center of Beersheva still resembles a frontier town.

Under a warm winter sun, Bedouin tribesmen in layered dark flowing robes, with long curved knives dangling from their belts, hurry about their business in the busy streets of the old town of Beersheva, the gateway to the Negev desert, much as generations of their forebearers have done before them. In this modern day, the Bedouins, who still come to town leading caravans of camels to the early morning market, cross paths with bankers, shopkeepers, college students, desert scientists, ever-increasing numbers of tourists, and ubiquitous uniformed Israeli soldiers, the young women in distractingly short olive green skirts and the young men carrying their automatic rifles as casually as the Bedouins wear their knives, setting the guns down on snack bar counters as one might an umbrella. Despite the souvenir shops, travel agencies, banks, offices and department stores crowded into its small buildings, the old town center of Beersheva still resembles a frontier town.

For perhaps 4000 years, at least, the town’s site, with its plentiful underground water and a large wadi (a dry bed that becomes a rushing river during the rainy season), has been the principal crossroads for routes into and out of the Negev. Abraham, according to the Bible, gave Beersheva its name when he dug a well there as a sign of accord with his new neighbors. Despite its long history, however, Beersheva never housed more than 5,000 people at any one time before World War II. The old town of squat, nondescript shops, houses and oasis parks dates back only to the beginning of this century, when it was laid out by a German officer in the Turkish army during the waning days of the Turks’ 400-year occupation of Palestine. It filled up with Arab Palestinians during the 1940s, but they left with the coming of Israeli soldiers during the 1948 “war of independence.” The troops found the town’s buildings abandoned and streets empty.

Today, Beersheva is lively again, and growing as never before. With a population of 100,000, including some returned Arabs and many new Jewish immigrants to Israel, Beersheva has become one of the country’s larger cities. It is the governmental, economic, educational, social and cultural capital of Israel’s relatively vast southland – the desert plateau that stretches from the Judean mountains south to the Gulf of Eilat on the Red Sea, and from Israeli-occupied Sinai east to the Dead Sea and the Jordan border.

In the Beersheva now being built are some of Israel’s most modern and imaginative neighborhoods, where apartments, houses, offices, stores and community services are mixed together in unusual architectural shapes and experimental arrangements on the landscape. Begun during the last decade and still being added to, these harbingers of Israel’s urban future are located just a mile or two from Beersheva’s still bustling old desert outpost town center.

Between these two in space and time lie neighborhood after neighborhood of deteriorating wooden duplex houses, two-story cinder block four-family flats, and three and four story pre-cast concrete apartment buildings – all surrounded by dusty, trash-strewn open spaces. The worst of these blocks of housing, put up during the 1950s, resemble the remaining colonies of World War II “tempos” and government housing projects for the poor in the United States. The best are almost exactly like the uninviting sprawls of cheaply built walkup apartments in American cities and suburbs.

Each of these Beersheva neighborhoods represents a successive stage in the sometimes frantic effort to design and build tens of thousands of new homes fast enough for Israel’s dramatically increasing population. A tour of their streets and walkways reveals the brief quarter century history of community building in the modern nation in much the same way that the layered rains of the countryside’s many archaeological digs lay bare the progression of settlements of many peoples there through the centuries. During that long history, the population and degree of civilization of this small, difficult land rose and fell sharply as one conqueror after another swept through it; the first Hebrews themselves pushed aside ancient Canaanites and Philistines. Yet no other force, not even the great occupations of the land by the Romans, Persians and Turks, has so changed its face, for better or worse, as has the resettlement and building boom since the creation of the present state in 1948.

There were less than one million permanent citizens, Jews and Arabs, living in Israel when statehood was achieved. Today, there are well over three million, not including residents of the occupied territories Israel took from neighboring Arab states during the 1967 war. Nearly 1,500,000 of the increase have been immigrants, mostly Jews exercising their right under Israeli law to return to what they consider their ancestral homeland. Continued immigration is vital to Israel’s national security and economic growth, its officials have said again and again, so it was important that newcomers find decent housing in livable neighborhoods and communities where they could be successfully integrated into Israeli life.

This task was far too big for private developers, who lacked the size, capital and expertise to build on a large scale until the 1960s. They were just beginning to participate when, during the middle of the decade, tension and war in the Middle East temporarily discouraged immigration and combined with a sharp economic downturn the Israelis call “the depression” to ruin some developers, while many of their buildings were left unfinished and empty. Today, private builders have taken over a large share of the market, but with a new influx of immigrants, the demand is outracing the developers again, and there is a growing housing shortage. As a result, the national government, which has already built almost two-thirds of the 750,000 permanent new housing units constructed in Israel since 1949, still must share a heavy part of the construction load.

This role is taken as a matter of course by the government in Israel’s socialist welfare state. It is especially expedient for the government to build housing for new immigrants who cannot afford to buy or rent their own at first. The government’s size as a builder also makes it easier to control and direct experiments in housing design, construction methods and community planning.

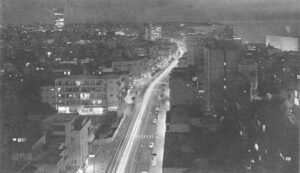

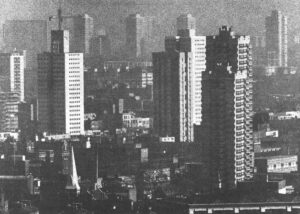

In addition to providing for large numbers of immigrants, Israel’s national housing policy is also designed to shift as much new development as possible away from its big coastal cities. Tel Aviv and Haifa have been expanding rapidly because of their varied, well-established urban characters and their locations on the Mediterranean Sea, which also makes them the principal places of entry for immigrants. Israel wants to distribute the population more evenly throughout the rest of the country, especially in those areas nearer the borders of neighboring Arab nations, both to improve security and to better balance the nation economically. Israeli planners are also concerned, as are their counterparts in most developed countries, with trying to prevent the uncontrolled growth of large cities, which has inevitably led to the deterioration of urban life and the environment. Sprawling Tel Aviv is crowded with traffic, even though the high cost and taxation of automobiles keeps many families from owning them. Haifa, a San Francisco-like bay city that is climbing up the side of picturesque Mount Carmel, is blighted by blinding, foul-smelling gases emitted from its port area petro-chemical industries. Both cities also have begun to unravel in loose strings of dull, single-dimensional bedroom suburbs.

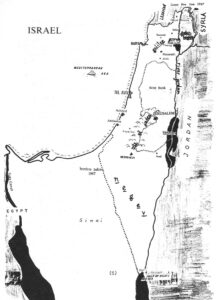

To provide an alternative, Israel’s Ministry of Housing, with help from other government agencies and donations from outside the country (including “reparation” money from West Germany), has fostered thirty “development town” projects scattered throughout the country. These new communities are of three kinds: massive modern additions to such large, well-established old towns as Nazareth, Safed and Tiberias in Galilee; the almost complete rebuilding from scratch of largely abandoned communities like Beersheva in the Negev and Ashkelon on the Mediterranean coastline near Gaza; and a startling number of brand new towns and cities rising where nothing had been before (at least since ancient times). Among these new towns are Kiryat Shmona, tucked in a geographic cul-de-sac near the Lebanese border; Ashdod, a brawny new seaport south of Tel Aviv with already more than 50,000 residents; Eilat, on the Red Sea; Kiryat Gat, a fast-growing industrial new town in the middle of a productive agricultural area reclaimed from the desert north of Beersheva; and the newest of the new towns, Karmiel in the Galilee and Arad in the desert wilderness overlooking the Dead Sea, each being planned and built in exacting detail, from the mix of socio-economic attainment and national origin of the families to be placed in each building and neighborhood right down to the view from each apartment window and the direction from which the sun will shine and the wind will blow.

Most of the land for new towns is already controlled by the Israeli government, which owns only some of it outright. Other land is held in trust by the government for its absent Arab owners, from whom the land would be purchased when negotiations are possible and for whom remunerations are accruing in the meantime. Still other land, the largest share, is owned by the Jewish National Fund, which pre-dates the Israeli government and has for many years solicited money from Jews all over the world to buy land in Palestine from absentee Arab landowners. By legal agreement, the Jewish National Fund holds this land in trust for the national government, which in turn has authority over what is done with it. It is estimated that 90 percent of Israel’s land is thus controlled or owned by the government. The remainder, mostly in and around built-up Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem, is owned by individuals who waited for values to go up, as they have spectacularly, to the point where the government can no longer afford to purchase it. The government maintains control over its land in new towns by leasing it, rather than selling it, to the buyers of housing and businesses, and to the local town governments. This gives government planners more say over what happens to the land, from the beginning of the building of a new town well into the years that follow.

Most of the land for new towns is already controlled by the Israeli government, which owns only some of it outright. Other land is held in trust by the government for its absent Arab owners, from whom the land would be purchased when negotiations are possible and for whom remunerations are accruing in the meantime. Still other land, the largest share, is owned by the Jewish National Fund, which pre-dates the Israeli government and has for many years solicited money from Jews all over the world to buy land in Palestine from absentee Arab landowners. By legal agreement, the Jewish National Fund holds this land in trust for the national government, which in turn has authority over what is done with it. It is estimated that 90 percent of Israel’s land is thus controlled or owned by the government. The remainder, mostly in and around built-up Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem, is owned by individuals who waited for values to go up, as they have spectacularly, to the point where the government can no longer afford to purchase it. The government maintains control over its land in new towns by leasing it, rather than selling it, to the buyers of housing and businesses, and to the local town governments. This gives government planners more say over what happens to the land, from the beginning of the building of a new town well into the years that follow.

Besides building most of the housing, places of business, and various local government facilities and schools, the Israeli government plays an active role in moving people and commerce into the new communities. Its immigration agencies encourage newcomers to move to them with offers of jobs and large rent subsidies. The rents and prices of apartments and homes in new towns are kept generally lower than those in the big coastal cities to attract “veteran” Israelis to them. Merchants and industries are offered a wide variety of inducements to move to development towns, and both citizens and businesses who relocate are also rewarded with tax reductions.

The problem then becomes one of keeping them in the new communities. This task involves much more than merely a large financial investment by the government. It means finding through trial and error the answers to several key questions. How should planners lay out new towns to infuse them with the vitality of urban life that makes Tel Aviv and Haifa so inviting? How can housing, stores and government buildings be made more attractive, yet also more efficient and inexpensive to build? How can sometimes antagonistic climate be coped with? How can immigrants and veteran Israelis of widely varying ethnic, economic and cultural backgrounds be integrated into a single stable community?

The decision of the Israeli government, on the very morrow of achieving statehood, to embark on an ambitious program of new urban community building was clearly extraordinary. Not only because of how it would add immeasurably to the great cost of setting up a new nation while maintaining an expensive preoccupation with military defense, but also because it was in some ways at odds with the anti-urban outlook of many Jewish pioneers who came from crowded conditions in Europe and elsewhere to settle in Palestine during the time it was controlled by the Turks and (after World War I, under a League of Nations mandate) Britain. These early immigrants believed strongly in abandoning their former lifestyles to “return to the land” as rural residents and farmers. Their largest communities were kibbutzim and other forms of agricultural and rural residential cooperatives; they were opposed to building urban settlements in the interior of the country. Their influence remains strong today through governmental officials who, by law, must approve at a national level the use of agricultural land for any other purpose. Because such requests are seldom granted, the Ministry of Housing has never been able to consider for new communities many areas with geographical and climatic advantages that might make them ideal for urban settlements. “Agricultural land,” a Housing Ministry planner told me, “is one of our holy cows.”

In addition to these limitations, Israeli town planners were even more tightly shackled by time and money. The new nation was flooded with Jews fleeing war-ravaged Europe and neighboring Arab countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Little more could be done in the beginning than to build the most inexpensive housing as quickly as possible. Thousands of one- and two-story row buildings, many of them duplexes and others groups of flats, were constructed of wood and hollow concrete blocks. As time went on, some pre-cast concrete walls were used, but the housing remained flimsy overall.

For patterns into which to place these buildings, along with necessary shopping, employment and community services, the planners turned to the “garden city” concept most of them had learned in Europe. This utopian scheme, born of late nineteenth century disillusionment with the growing congestion and filth of western European industrial cities, envisioned the building of idyllic suburban communities of small cottages amid spacious green areas along curving streets in neighborhoods separated from the bustle of the community shopping area and places of employment. Many of our latter-day suburbs, regional shopping centers and industrial parks are products of this concept, as are many of the “new town” projects of Europe and the United States. Most of these developments, however, have evolved into dependent satellites of ever enlarging central cities and have grown to share many of their problems. Those that have remained pleasantly bucolic have relied on housing densities so low that only middle class or wealthier residents can afford to buy homes there.

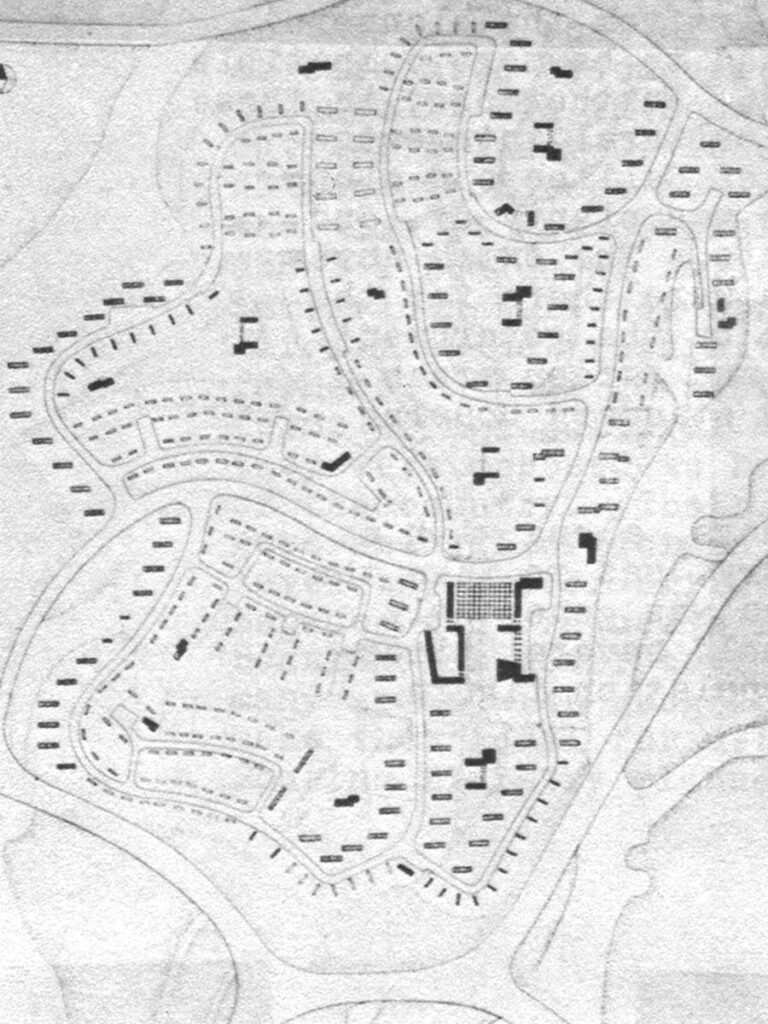

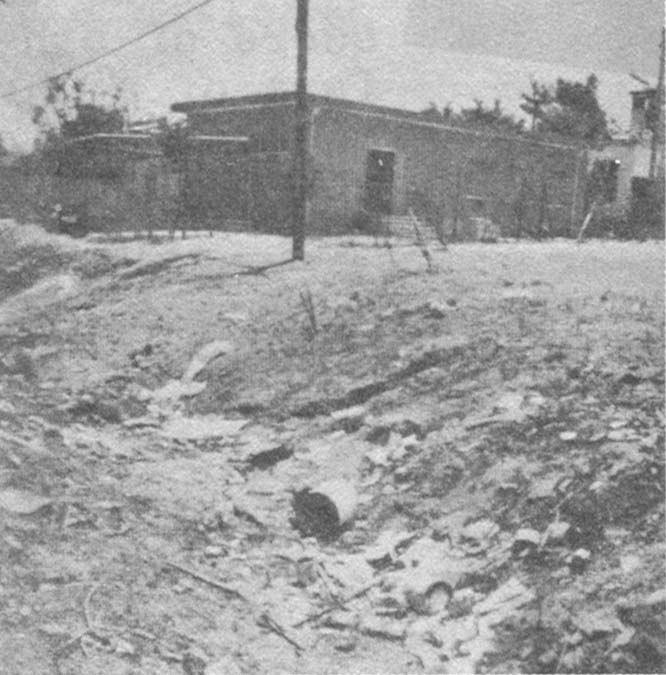

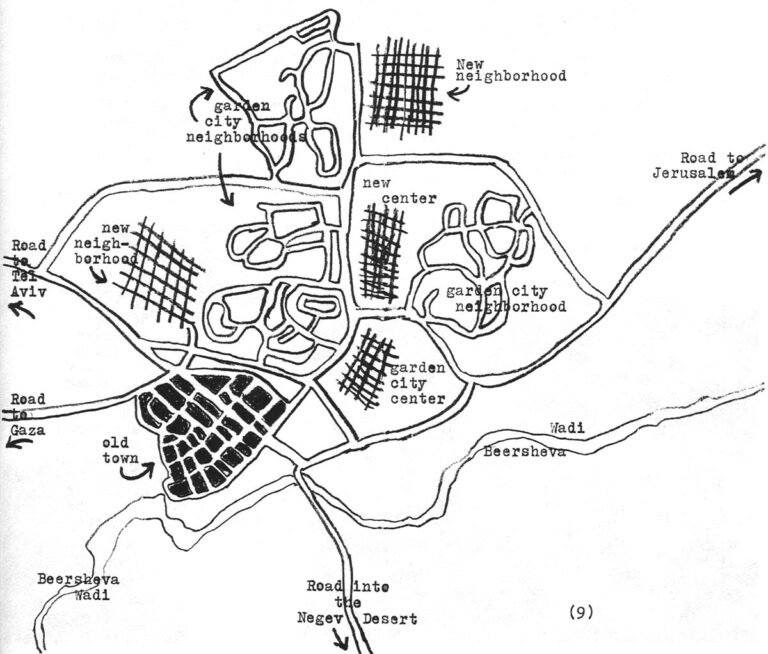

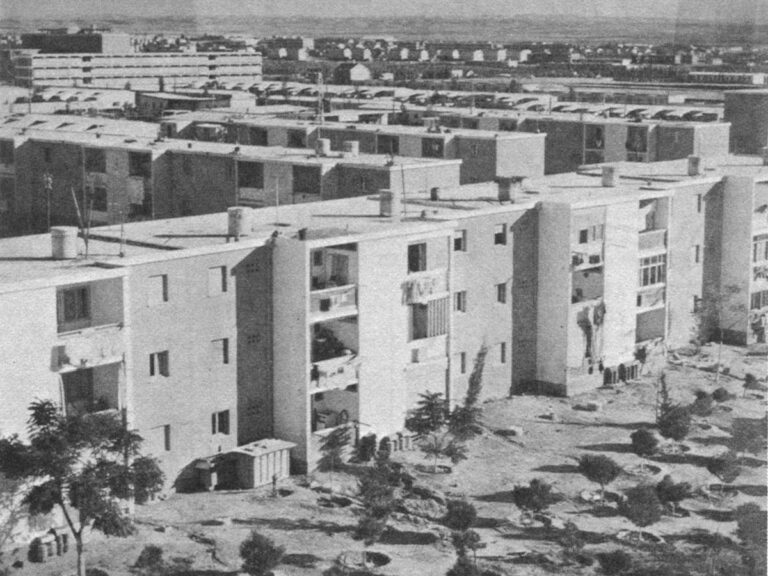

The plan for one of Beersheva’s garden city neighborhoods (top left) looks much like that of U.S. Levittowns. What happened to some of the area’s “green spaces” can be seen at right and below.

(Government photo)

In Israel, for the first time, the garden city format was to be utilized to build completely independent communities relatively far from existing cities, rather than for satellite suburbs. In addition to flowing logically from the planners’ backgrounds, the garden city format seemed to be more compatible with the notion of remaining on the land. Furthermore, in those areas where there were no competing agricultural interests –particularly in some of the rocky hills of Galilee and along the vast edge of the Negev desert – there was plenty of land to spare for such low density developments. The extra acres needed for the ring roads and greenbelts were there for the taking, and most were already controlled by the government. It was also hoped that the public space and garden areas might help compensate for the plain, low standard housing that had to be built at first.

Thus the rebirth of ancient Beersheva, along with a score of other projects across the country, was to take the form of a garden city. The new Beersheva was generously mapped out for an area that could have held several times the 60,000 first projected as a final population figure.

It was to be divided into several sprawling neighborhoods separated by wide greenbelts that would point inward to a central park and new shopping and government center. The old town, which was left at the southern edge of this plan, was expected to dry up and eventually vanish. On paper, the master plan looked very much like that for “planned” suburban neighborhoods still being built in the United States.

As time passed, Israel’s garden cities failed to bloom, however. Rain is absent from Beersheva, for instance, half the year; when it does come, it is often in the form of flooding torrents. Consequently, the planned greenbelts and flowering yards remained parched or washed out sandlots. The lack of shade left the sun beating down unmercifully on poorly insulated and ventilated little houses that were too far apart to be of any protection to each other. Meanwhile, the old town, more suited to the climate with its crowded, overlapping buildings and protective trees, provided an oasis that grew steadily rather than dying out, even though it was some distance down the main road from most of the housing. The long distances and overall low density of the project caused the city engineer to complain about the prohibitively high costs of providing water, sewers and utilities to homes, stores and businesses. Only Beersheva’s location as the entrance to the Negev, with its newly found mineral wealth and important passage to the southern port of Eilat, kept it growing during those years.

BEERSHEVA: The old town (top) with its mosque, built by the Turks; a “habitat”-like apartment tower in a new neighborhood (bottom left), and simplified town map, showing the tight knit old town to the south, the meandering streets of the various spread out “garden city” neighborhoods surrounded by gaping open spaces that were to be greenbelts, and the new neighborhoods and new town center (cross-hatched areas) now being built.

Even in locations elsewhere in Israel where the climate was not quite so brutal, gardening proved to be less than popular among immigrants who had really never done any before and now had far too little time or money to invest in it. Maintenance of the sprawling exposed public areas and the cheaply built housing grew more and more expensive until it finally ceased altogether in many places. Playgrounds became mudholes and open spaces garbage dumps. One development after another took on the dog-eared appearance of the dreary “projects” that public housing programs have so often produced in the United States. As soon as they could, immigrants in these developments moved out and went to the coastal cities, while veteran Israelis stayed well away from the new “immigrant towns.”

At this point, the Housing Ministry began building more substantial three-and four-story apartment buildings with larger rooms, balconies, porches and patios. Most of the buildings were long, rectangular, buff colored and of pre-cast concrete, arranged more tightly in rows and squares than the old squat boxes, with better playgrounds and smaller enclosed planted areas. For the first time, already settled Israeli citizens were strongly encouraged by government financial inducements to move into these new neighborhoods along with immigrants to speed up the acculturation process for the newcomers.

But problems persisted. Although the housing was of a much higher quality inside, the sameness in size, shape and color of every building in every large neighborhood became, as one Ministry of Housing report put it, “monotonous in the extreme.” The lack of city conveniences and almost any trace of the everyday color and vitality of urban life also was very painful to both immigrants and veteran Israelis who moved to the new communities, as most did, from established cities or towns elsewhere. The planned town centers had not yet grown up in most of the projects. The nearest stores often were a long walk or a bus ride away. Very few development town residents had cars. Unlike American suburbanites, who have chosen to escape from cities and can always drive back into them whenever they choose, Israeli development town residents felt trapped in barracks in the wilderness.

As a result, Israelis and European immigrants with marketable skills, who had been lured to the new towns by lower apartment prices and tax advantages, turned around and left them as soon as they were able to save enough of their extra money to move to and live in sufficient comfort in a coastal city. They usually had little contact during their brief stays in the new communities with less skilled and schooled African and Middle Eastern immigrants whom they called “Oriental” Jews. By and large, the privileged Israelis and Europeans had been eased into the newest and best housing in the new towns, while the others had to be satisfied with the leftovers. Seldom did the same building contain both Israelis and immigrants of any kind, or even both European and Oriental immigrants. Thus, integration of newcomers and older citizens did not really take place, while the unremitting exodus from the new communities robbed them of their most skilled workers and experienced leaders. Increasingly, it appeared that the government was building glorified refugee camps for African and Middle Eastern Jews rather than complete new towns.

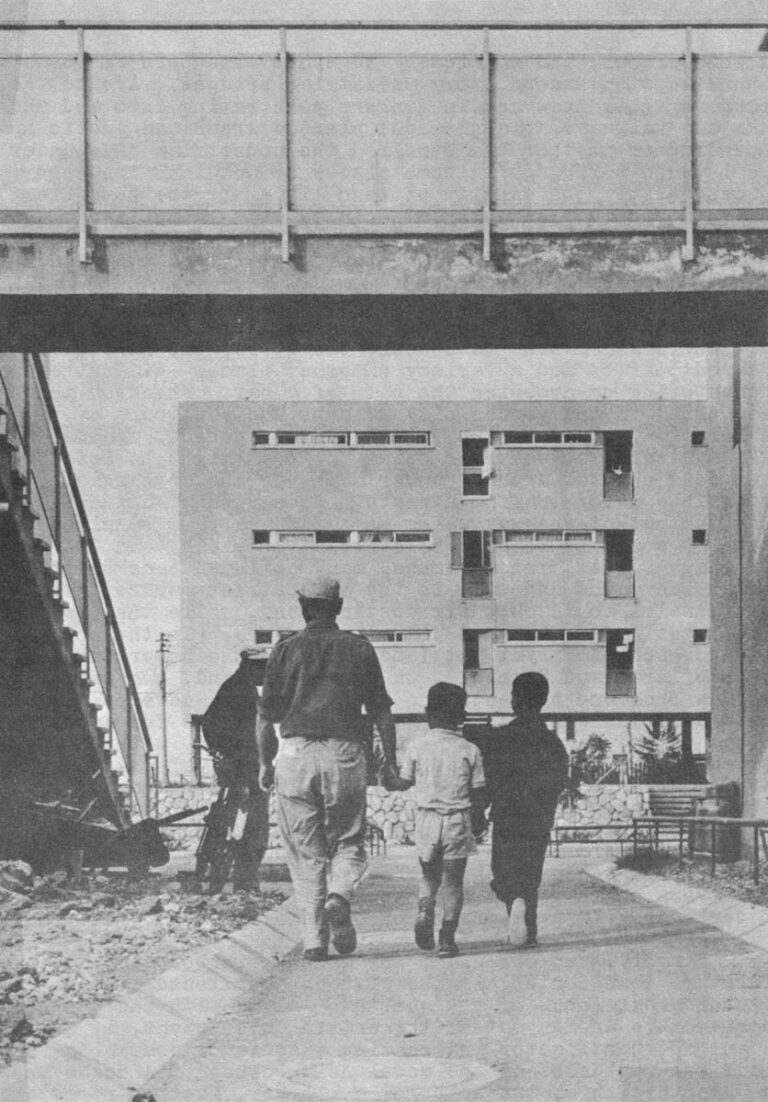

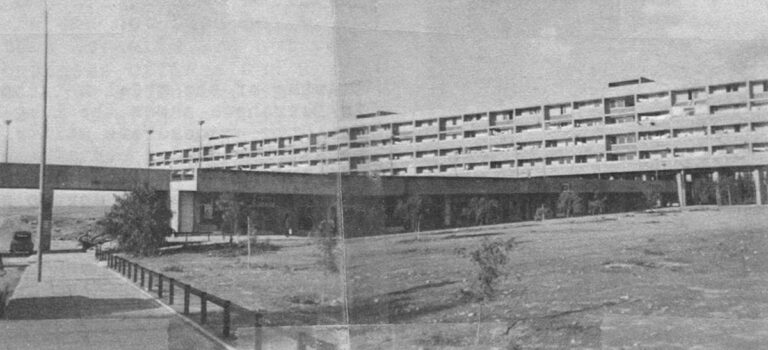

It was time for a thorough re-evaluation of the development town program; one self-critical Housing Ministry report after another documented the problems. Finally, it was decided to move away from the garden city concept with experiments in constructing bigger and more varied buildings and bringing more urban activities, particularly shopping, closer to the housing. In Afula and “Upper Nazareth” (the twin to the predominantly Arab old town of Nazareth), both built on fairly steep but scenic and pleasantly cool hillsides in Galilee, massive eight-story apartment buildings were planted on the slopes, with concrete bridges reaching out from the entrance on the fourth or fifth floor of each to connect with the sidewalks. The mid-building entrances eliminated the need for expensive elevators, thus turning the difficult terrain into an asset. On the ground floors of lower, more massive buildings, shops were built in. The bustle of commerce added new life to these neighborhoods. This idea was carried further in Beersheva, where groups of apartment buildings were placed in squares around small neighborhood mall shopping centers, with some of the stores and passageways for pedestrians located in the bottom of the apartment houses themselves. With well-tended trees and flowers blooming in protected planters, they are now pleasant areas where shoppers and apartment dwellers congregate.

Innovations: a shopping plaza surrounded by apartments and dotted with flora (top) in Beersheva…spacious but deserted town center pedestrian mall (bottom left) at Kiryat Gat…and concrete bridge connecting middle of apartment building to street (bottom right) in Nazareth.

These more lively neighborhoods were only isolated oases in otherwise dormitory-like development towns, however. Unfortunately, the first attempt to cope with the problem on a town-wide basis, to construct a cohesive, entirely new community with a character of its own, was still rooted too deeply in the garden city patterns of the past. This attempt, the new town of Kiryat Gat, southeast of Tel Aviv and northwest of Beersheva, has been an encouraging success in the effort to generate more economic activity in the country’s interior. But its widely studied master plan, drawn to produce a community that would grow up naturally around a lively center, failed in important ways, teaching Israeli planners hard new lessons.

Kiryat Gat was to be the urban focal point of an agricultural land belt. Numerous kibbutzim and other agricultural cooperatives had pushed back the edge of the Negev desert with irrigation and planting to produce profitable farms and new forests. The last urban settlements in the region dated back to the time when Samson was born in Gat, an ancient town whose stone remains are on a small hill uncovered by archaeologists. Not far from this site is where planners chose to put Kiryat Gat, where the pre-1967-border road from Jerusalem to Beersheva joined the road from Tel Aviv before turning south. It was to be the marketplace for the thousands living in the surrounding agricultural cooperatives, as well as the location for regional secondary and vocational schools and the seat of the area’s government.

Kiryat Gat was also supposed to attract industry to the region to supplement the agricultural economy. With national government help, it has succeeded so well at this that its initial industrial plant acreage is full, its population has increased steadily, and its residents are fully employed. This success has created problems, however, because the town never has fully filled its other role as “capital” of the surrounding area. Thus, a place that had been planned as a rural center became a factory town, a reality with which its garden city plan was unable to cope.

Like Beersheva as it was first planned, Kiryat Gat was to have several neighborhoods of spread out, small scale housing surrounded by greenbelts. Unlike Beersheva, its town center, begun with the first housing, was carefully designed as an urban unit around a large pedestrian square. Pedestrian pathways were to lead from each neighborhood to the center, where the town hall, a cultural center, synagogue and shops were clustered around a large flagstone mall. It is today a friendly, human spot unlike anything that came before it in the development towns, even though its stone and planted areas are not holding up well under the few years’ wear and tear. The center however is underused and many of the stores, offices and other buildings that were to be located here never arrived, primarily because the “garden city” neighborhoods within walking distance of it have been dying. Deterioration of the spread out duplexes and row buildings and the empty ground around them has been even worse than in Beersheva. Entire streets of Kiryat Gat neighborhoods, collectively called “the swamp” because of the mudholes that their “green spaces” have become, already have been abandoned by their residents.

New, much more dense housing of the late 1950s style, in rectangular block buildings, has been constructed beyond “the swamp.” These areas, however, have the usual depressing dormitory atmosphere about them today, and are also too remote from the town center to give it sustaining life or, in turn, to draw on it for satisfying urban activity. To better connect the two, pedestrian pathways soon were abandoned in favor of wider roadways for cars and buses. Kiryat Gat began to resemble the post-war Levittowns of the United States, except that massive look-alike Israeli apartment boxes had been substituted for the small look-alike Levitt box houses. The time clearly had come to abandon not only garden city housing types and neighborhood land use, but also the overall garden city community form as well. Fittingly, Kiryat Gat, the ruined garden city, became the first laboratory for testing its antithesis in an experimental model neighborhood to be built apart from the rest of the town, studied and modified as deemed necessary.

Two views of the monotonous dormitory-like pre-fab concrete apartments built for immigrants to Israel in the 1950s and early 1960s, at Kiryat Gat (top) and Upper Nazareth (bottom).

Israeli planners called their new concept the “integral habitational unit.” It meant simply the re-weaving together of those elements that had been separated to form garden cities. A start had been made in Nazareth, with shops located on the ground levels of apartment buildings, and in Beersheva, where apartment buildings were grouped around small shopping malls. Now, a single, integrated group of buildings would contain not only housing and stores, but also school rooms (which in garden cities were on separate campuses), the health center, library, cultural center and other community facilities. All of it would be accessible to everyone living there via pedestrian “streets” and walks that would widen in some places into public open spaces with playgrounds and green areas shaped and cultivated for their value as natural beauty rather than as barriers between one community activity and another. Essentially, this meant returning to the organization into which cities and towns have always evolved naturally, except that new configurations would be tried to re-admit light, return the greenery, and recreate the pedestrian spaces that had been squeezed out of most old towns and cities.

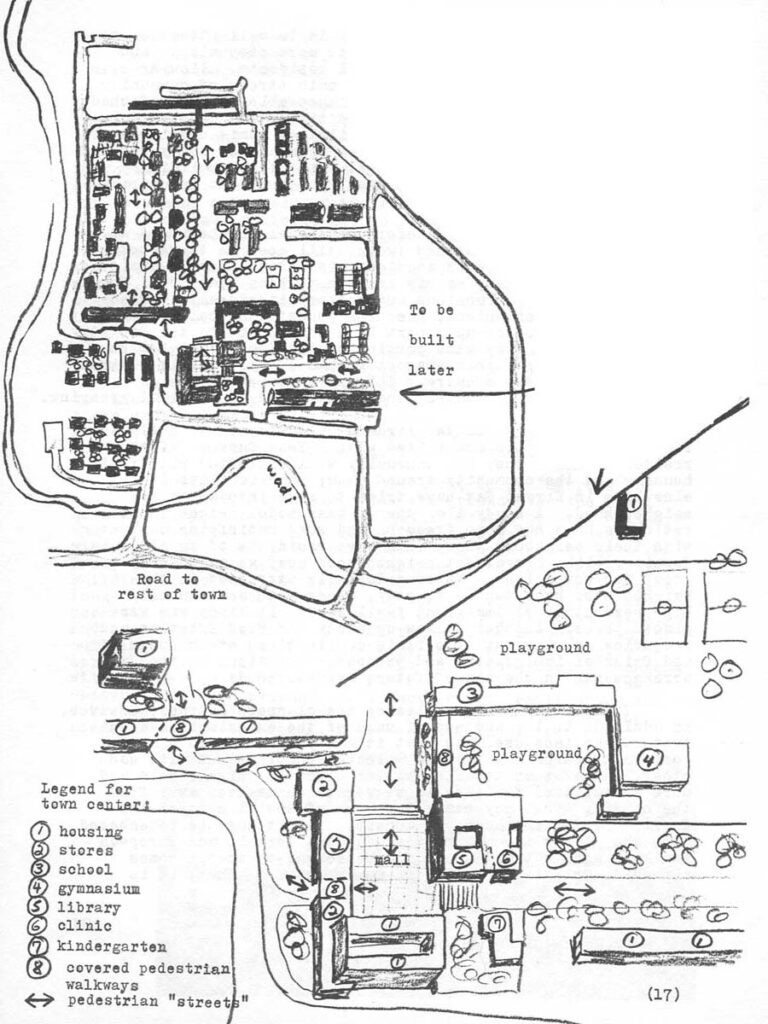

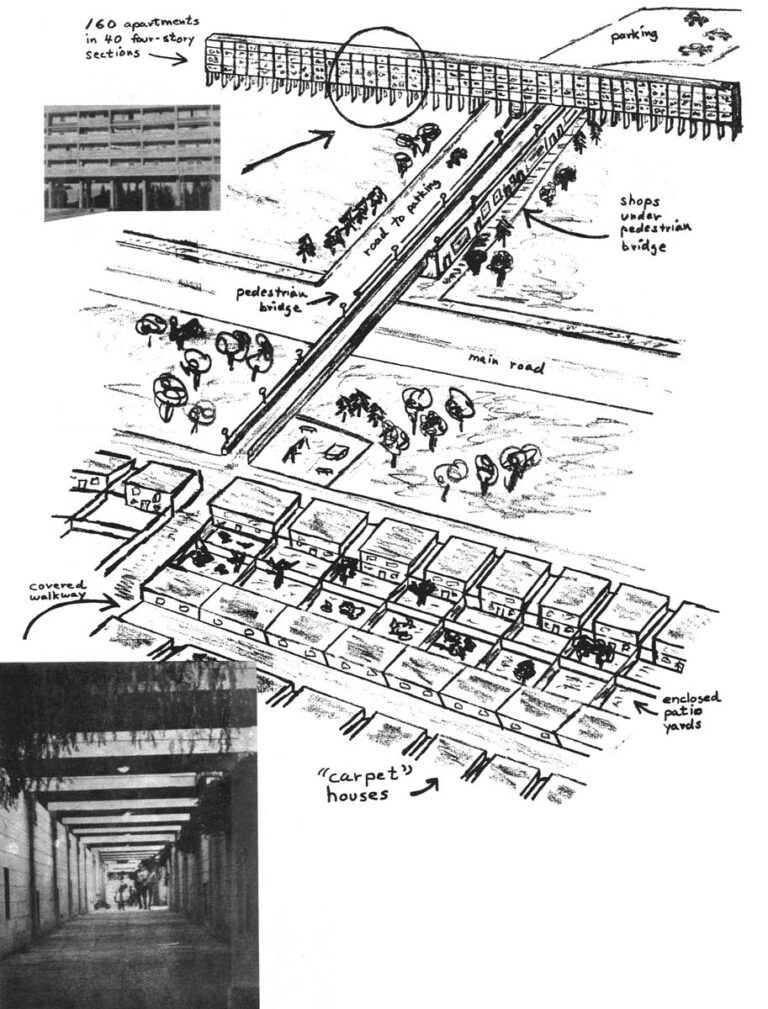

Model neighborhood (Integral Habitational Unit) at Kiryat Gat

At the top of the page is a simplified layout of the model neighborhood, which shows how the buildings are arranged in a variety of configurations along pedestrian “streets” and walled off planted areas. Cars are kept out on outer ring road and small fingers reaching in to parking areas. Arrows (<–> ) show main pedestrian axes. Town center, with shops, school, community services and housing all located together around malls and pedestrian walks is in center of plan, and separated out in large detail on lower part of page.

“One must first comprehend what a town, as a place of living and working, truly is,” wrote the late Israeli planner Arthur Glickson in describing how he began designing the pioneering model neighborhood in Kiryat Gat. “The town thrives on diversification, competition, and the integration of competing or opposite elements. In the course of the attempts to balance or relate the diverse elements to each other, life gains a new dimension and becomes urban life.”

Glickson’s work in Israel was among the first attempts to put the urban Humpty Dumpty back together again in some new way that would regain the close proximity of functions that is the advantage of city living, while maintaining a manageable scale. This idea, the reformation rather than rejection of city life, is now the basic philosophy underlying the planning of many post-garden city era new towns in Western Europe, and, for the first time in the United States, in the Cedar-Riverside project in Minneapolis.

In Kiryat Gat the model neighborhood was planned only after it was determined who would be likely to live there and, as a result, what would be best to build for them. Veteran Israelis and immigrants from Europe, the Middle East and Africa were to be mixed, even within the same building, in pre-determined combinations to be tested by the residents’ later interactions with each other. Their various family sizes and preferences for single or multi-family housing, attached yards or none, were all considered by planners who then designed a variety of building types – large rectangular apartment buildings, and attached houses with enclosed patios, some built one on top of the other with one family’s roof serving as another’s porch – grouped tightly around a central core. The buildings were placed around open malls and parks in some places, and so closely together elsewhere as to be connected with second story pedestrian bridges. Around the groups of buildings and in fingers penetrating into and under them are walkways, playgrounds, planted areas and public spaces. Depending on whether one strolled the pedestrian ways under and between buildings in some places or out into the open spaces, either the density of town living or the more free, airy atmosphere pleasantly associated with suburbia could be experienced. The stroller’s surroundings would be ever changing as he went along, turning corners, going in and out of enclosed and open spaces.

More important, it would be possible to walk almost everywhere – from home to school, the store, the health center, the post office and a variety of other places – without ever encountering or crossing the path of a car. Whenever this had been tried in the garden city suburbs and new towns of the past in Israel, Europe and the United States, narrow, meandering walkways were put wherever space for them might be left over. They were shunted around, under and over the more readily accessible motor traffic streets. As a result, unrealistically long and out-of-the-way walks were necessary to go places that actually could be reached more directly by car. In Columbia, Maryland, U.S.A., for instance, many children pass by the pedestrian paths and walk in the main streets, where there are no sidewalks to reach their destinations, while their parents simply get in the car and drive everywhere. In the model neighborhood of Kiryat Gat (and later in the newer development towns of Arad and Karmiel), on the other hand, the principal avenues from one place to another inside the development are the pedestrian walkways, while the main street for autos is out of the way, winding around the outside, with carefully placed traffic fingers leading from it into cul-de-sac parking areas. In this respect, the Israeli planners were taking advantage, for the moment, of the still low proportion of auto ownership in the country; the streets and parking lots did not yet have to be constructed to hold a large volume of cars, and the convenience of the minority of drivers could be put on a lower priority than the needs of the overwhelming majority of pedestrians.

Finally, the center of the model neighborhood, a miniature town center, is the obvious architectural and psychological focus of the quarter. Along with the unusual architecture and layout of the entire development, it was to be an important factor in creating a sense of community place for residents of the model neighborhood. A dozen shops, the health clinic, two schools, a library, meeting rooms and a cultural center grouped around a large interior plaza reached by many avenues of the pedestrian network – this core is built up in a larger, more easily identifiable mass than any other buildings of the neighborhood. This is to call attention to it, make building its component parts more economical, and increase social contacts among local residents, allowing even school children to pass through the main stream of community life each day. This mass creates innumerable pockets of shade for hot summer days, and both it and the entire quarter were planned so that openings between buildings admit cooling east-west breezes and allowed a good view from almost everywhere of the green Judean hills to the east, while large buildings mostly block out the much less scenic highway and industrial area to the north.

Arthur Glickson died before the model neighborhood at Kiryat Gat could be finished (work still goes on there today). But its several completed sections, including much of the core center, show that many of his goals have been realized. The neighborhood is a harmonious and yet architecturally varied community on a convenient, pleasing pedestrian scale. As described in a follow-up report by a consultant to the Ministry of Housing, “The completed portion of the (model neighborhood) has assumed a more urban character than any previously planned neighborhood in the country. This is apparent in the diversified building masses, the skyline and the spatial grouping.”

Its carefully located gardens have bloomed with flowers. Its pedestrian malls are filled with life. Surveys of the residents showed they are unusually well satisfied with their housing and the community around them; many families living elsewhere in Kiryat Gat have tried to move into the new neighborhood. A study also showed that model neighborhood residents have had more frequent and more satisfying contact with their neighbors there than have residents of an old dormitory-like Kiryat Gat neighborhood used as a control group for comparison. Veteran Israelis attracted to the neighborhood have tended to stay, along with an unusually high percentage of immigrant families of all kinds who were placed there. Another follow-up study did find friction and prejudice growing out of certain combinations of European and Oriental immigrants, and proposed variations on those arrangements in the mix of future neighborhoods.

The primary positive lesson the planners learned, however, in addition to the success of much of the experimental architecture and land use, was that it was preferable to place certain kinds of families in selected combinations with each other, rather than to allow better educated, higher paid and more assimilated families to segregate themselves away from the others. This may smack too much of social control for Americans, for instance, to accept. Yet it must be remembered that the higher income, better educated Israeli and European families were not and could not be forced to accept homes alongside Oriental and African immigrants. Rather, it is necessary for the government to make the quality of the homes and the overall community, as well as price and other benefits, attractive enough to bring and keep them there.

The model neighborhood has not put all of Kiryat Gat back together again, however. It is only one relatively small part of Kiryat Gat and is somewhat cut off from the rest of the town by its unusual design and, ironically, the planners’ success in focusing the neighborhood inward toward its own center. That center is just not large or varied enough, however, to satisfy anywhere near all needs of its residents, who must still go to the town center of Kiryat Gat to find a large supermarket, other more diverse shops, the cinema, many government services and the like. But the town center is just not closely tied to the new neighborhood, or anywhere else in Kiryat Gat, for that matter, by the kind of convenient inviting pedestrian network that makes the model neighborhood’s center work well on its limited scale.

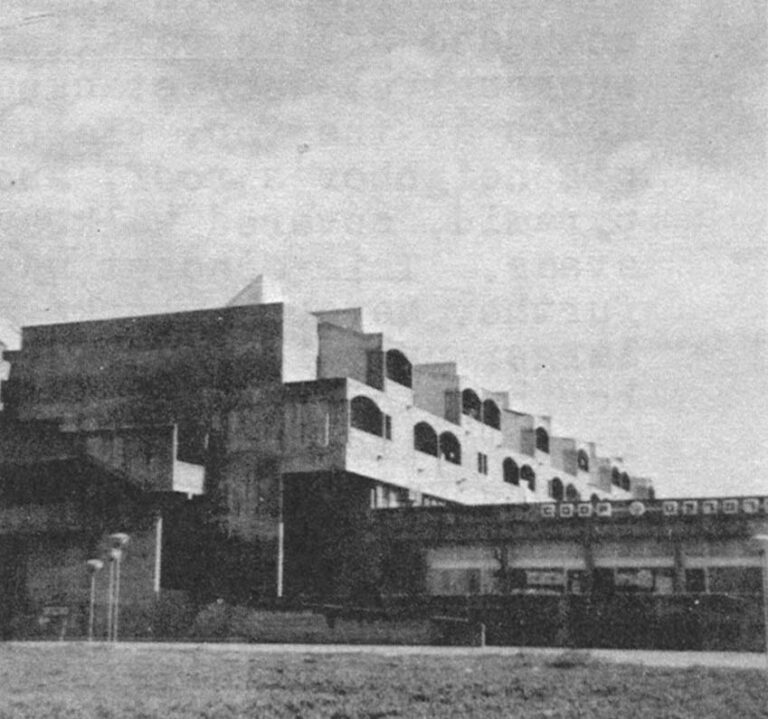

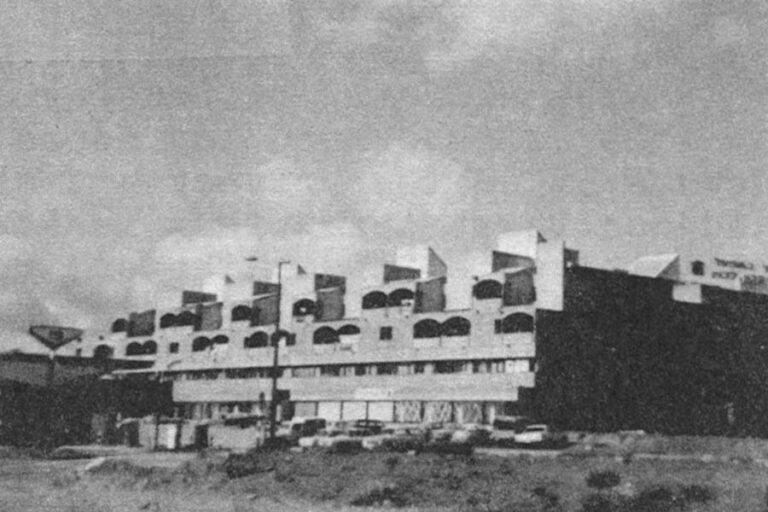

The same kind of problem is evident in Beersheva, where another model neighborhood, begun a few years after that of Kiryat Gat, and several scattered buildings have further tested the idea of closely mixing urban functions again. Although these experiments have yet to be successfully integrated into Beersheva’s still confused community structure, they remain among Israel’s most daring in design and execution.

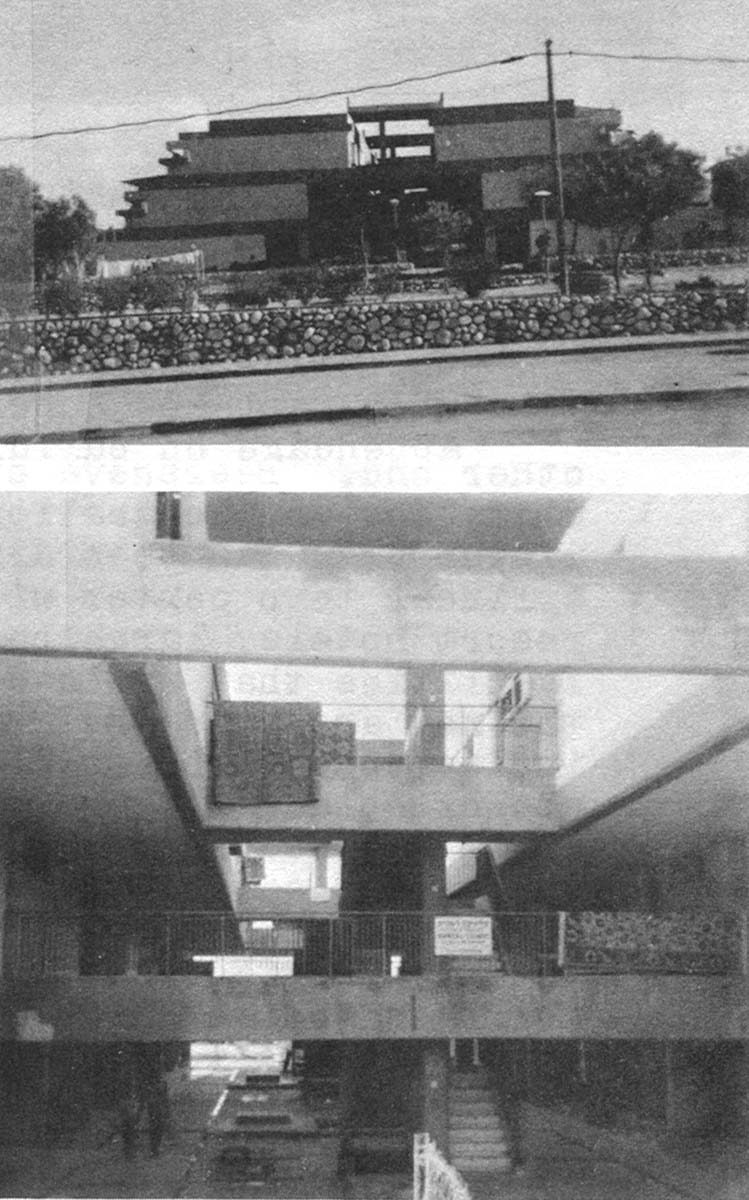

In Beersheva’s model neighborhood, large “carpets” of low, flat-roofed, attached houses are spread over the level ground. They have been woven together around covered walkways and walled-in patios and gardens protected from the desert wind and sun. Across the neighborhood’s main street from one group of “carpet” houses is a spectacular narrow, rectangular building – four stories high and three or four football fields long – that has been pushed up off the ground on forty pairs of concrete piers. Rows of trees and bushes, pedestrian walkways, and even a road leading to a parking lot, pass underneath the building. A long pedestrian bridge extends from its side across a large swatch of ground and the main street to connect with the carpet houses on the other side. It is a severely modern, concrete, inverted Ponte Vecchio with small shops and cubicles that reach down from it to the ground to form the neighborhood’s commercial, civic and health center.

Drawing of the model neighborhood in Beershava shows the long apartment building on concrete stilts, with a pedestrian bridge containing shops and community services connecting it to carpet houses across street. At left is interior view of covered walkways, protected from desert sun and wind, in between rows of carpet houses (arrow in drawing left).

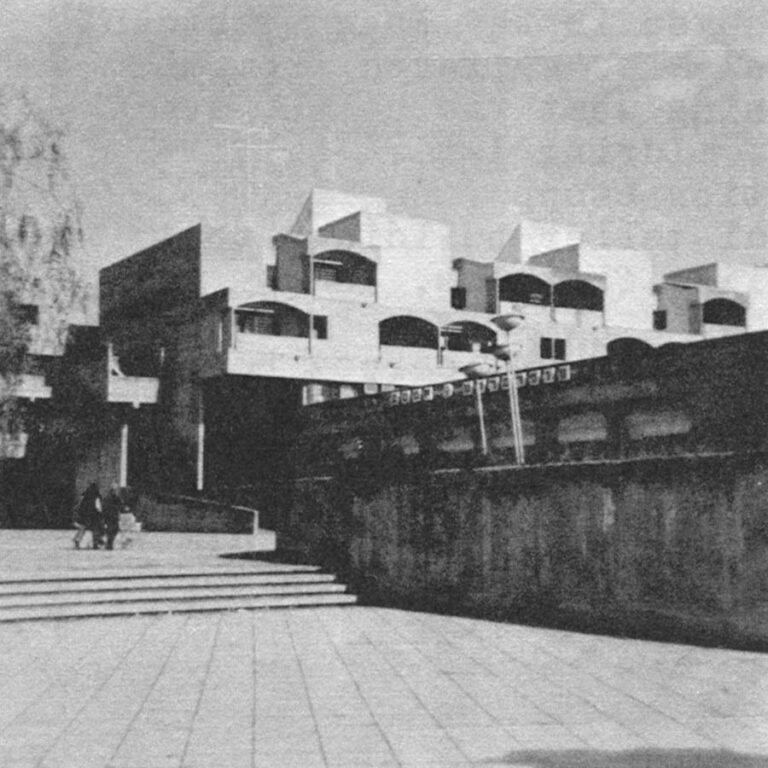

Greater density, the covered spaces of the carpet houses and the open views of the raised building were combined elsewhere in Beersheva in a single pyramid-like apartment building, composed of two parallel rows of three stories of flats, each successive story stacked closer to the center until they almost touch at the top. Each apartment has a private patio on top his neighbor’s roof, and inside the pyramid, covered walkways and play areas. This concept was carried even further several blocks away in a much larger pyramid that also has space for business offices and stores on lower floors, including an arcade of sorts on the yawning cavity inside the building and a supermarket appended onto the outside of it. Walks and stairs lead every which way in and out of the building, which is virtually a small community in itself. An imaginative arrangement of modernistic covered porches on the upper floor apartments gives it a “habitat” look.

“pyramid” apartment house in Beersheva from the outside and inside.

“Pyramid” structure of housing, offices and stores in Beersheva. Note in upper right view, on right side of building, opening to inside arcade. Other views show mall and supermarket appendage on building’s other end.

Although it is this very kind of multi-purpose, architecturally varied structure that has become the primary building block in some of the larger, more urban satellite new towns in Europe, this striking building is not yet a financial success in Israel. Many of its shops and offices are not rented and another planned half to the structure has not been built. It may be that Israelis are nat yet ready for business offices and apartments in the same building; or it may be that its design is just too daring. More likely, though, the building suffers most from its isolation in an area still being developed on one end of town while most business gravitates around the old town at the other end. Beersheva even today suffers from the great distances and separations of its garden city origins. A new master plan has been drawn to try to correct this by building a linear town center with government offices, college campus, resort hotels, large business offices, major stores and other facilities that would connect the old town on the south with the new areas to the north. Theoretically, new housing influenced by the model neighborhood and other experiments would replace the near slums in the old garden city nearest the new linear center’s site. All these elements would then be tied to each other by a new network of pedestrian ways. The new town center is progressing quickly, which illustrates the vitality Beersheva draws from its location, its growing colleges and research facilities and its lucrative businesses. But it may be too late to prevent its becoming a “drive-in” center reached primarily by car along the new, big roads that have been built to link Beersheva’s presently far-flung neighborhoods.

During less than two decades of experimentation, then, Israeli planners reached a point in the 1960s where they knew what was not working, and had an idea of what might work if it could be tried on the scale of an entire new community. They were ready to abandon completely the garden city, but were still restricted to patching up garden cities when it came to experimenting with new ideas. They had built individual neighborhoods that seemed to work, but had yet to create a complete town as cohesive as only naturally-evolved towns seem to be. They had successfully integrated apartment buildings here and there, but most development towns were still “immigrant towns,” stigmatized by their unfortunate beginnings. It was time once again to begin anew, even though the government was ill-equipped financially to do so, and start totally new towns based entirely on new concepts of community building rather than those of the past. Only in this way could they find out if really workable cities could be created in one stroke by government planners, rather than only molded by years, decades and even centuries of happenstance growth – the kind of growth for which Israel still does not have time.

[This is the first of two newsletters on the new towns of Israel. The second will describe the second generation of new towns now being built there.]

Received in New York on February 4, 1972.

©1971 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article my be published credit to Mr. Downie, the Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.