San Jose, California

October, 1971

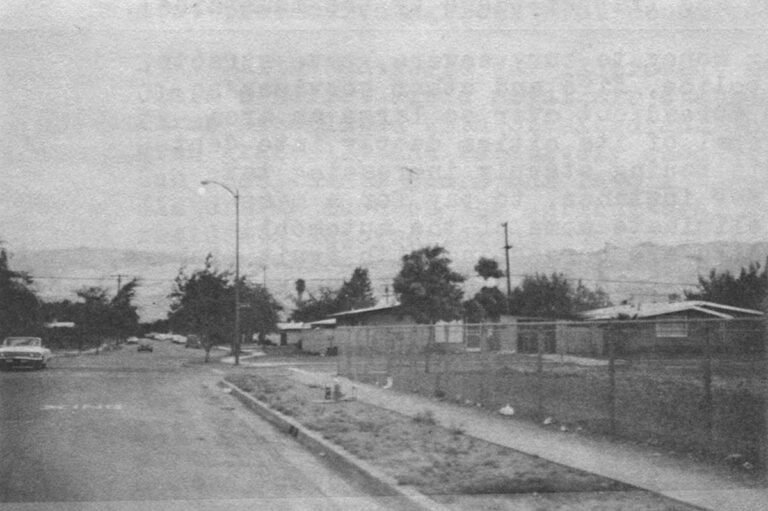

Eye-smarting, mustard-colored haze hides all but the shadowy outlines of the mountains on each side of the long, flat valley. Automobiles push and shove through crowded concrete and neon strips of stores, service stations, car lots and taco stands. Here and there, small isolated groves of the last surviving fruit trees fight strangulation by the surrounding subdivisions, factories and freeways. Acres of roofed box houses huddle tightly together, back to back and side to side, without open spaces, parks or even sidewalks. Many tattered homes just ten years old slouch in ready-built slums, their gravel roofs leaking, concrete slab foundations cracked, flimsy veneer doors and walls warped, stick fences rotting and sparse dirt yards alternately flooding and heaving.

A visitor’s first impressions of Santa Clara County, California, are quite consistent with the reputation that it and its largest city, San Jose, have gained as notorious examples of suburban sprawl. The rapid urbanization of the Santa Clara Valley just south of San Francisco Bay during the past twenty years has recently been the subject of highly critical detailed studies by a group of “Nader’s Raiders” and an independent team of Stanford University law students, and was grist for the news magazine mills before that. “Urbanists cite it as the archetypal slurb, a sprawling confusion,” Business Week observed. “Growth came so fast… and with such disastrous results,” Newsweek concluded, “that the experience serves as a dire warning of what can happen if residents fail to watch what is happening to their community.”

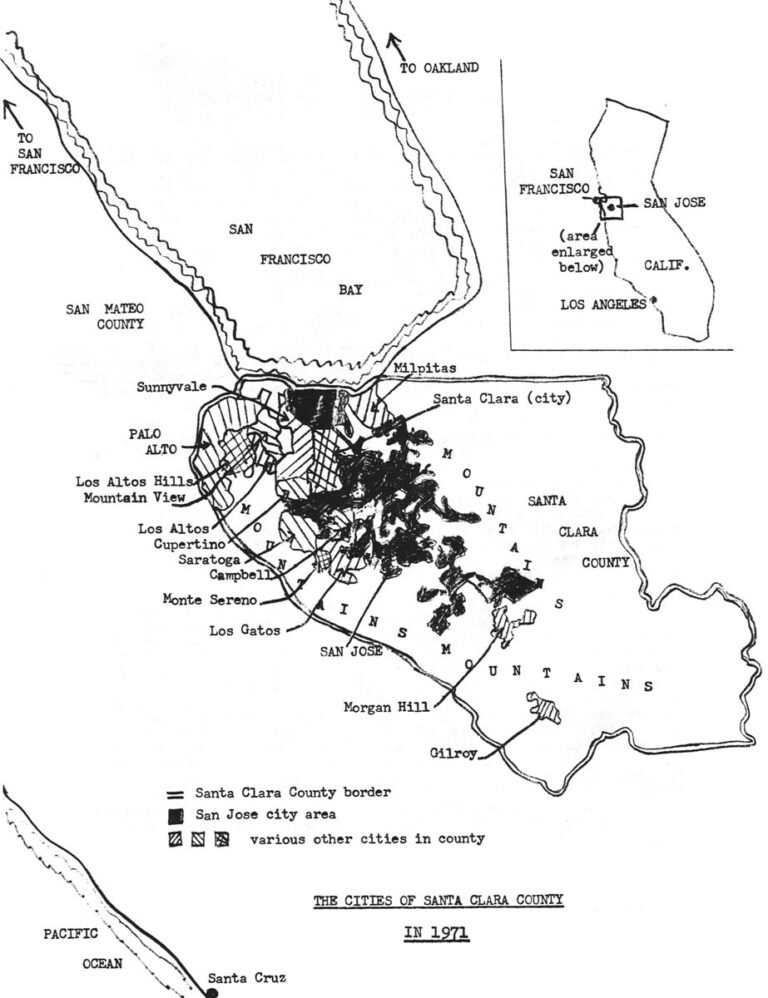

What happened here cannot be neatly explained by the old cliches of suburban sprawl. Santa Clara County is not a single-dimensional bedroom community for San Francisco to the northwest, for instance; it has industry and other economic resources of its own, including the huge plants of Ford, Lockheed, General Electric and IBM (which Khrushchev toured during his 1958 visit to the United States). The valley floor was not empty, low-priced land before the developers arrived; it was one of the most productive agricultural regions in the nation, filled with highly profitable orchards and small businesses where the trees’ fruit was processed. The rapid residential and industrial development of the valley has not taken place in a governmental or civic vacuum without planning; Santa Clara County and several of its cities have had strong charter governments, model planning and zoning laws, and large staffs of professional planners, while the citizenry includes academic leaders at Stanford University (located at Palo Alto in the county), corporation executives and a well-educated, well-paid labor force. Not just tract houses and cheap walk-up apartments have filled the county; there are also whole communities of substantial homes that each cost $50,000 to $100,000 and up and are built on lots of one-half to several acres in size. Santa Clara’s population is not a homogeneous slice of society; rather it is a mixture of wealthy, middle class and poor, city and rural people, white and black and Mexican-Americans.

For these reasons in themselves, the self-destruction of Santa Clara County warrants close study of how and why it happened, and what lessons are there to be learned by other communities. Surely, of all fast-growing suburban areas in the country, there existed here the potential for bringing about something better.

In addition, those who remember the Santa Clara Valley of just twenty-five years ago lament especially the loss of great natural beauty and a balanced productive agricultural economy. It has always been an unusually fertile valley, stretching south from the bay about sixty miles between low ranges of attractive wooded mountains, with a balmy Mediterranean climate that produced sufficient rainfall in a few weeks each year and left the sun shining warmly the rest of the time.

“The land in the valley was of the very highest quality,” as Karl Belser, a discouraged former county planner, has described it in a retrospective analysis written after he resigned his post. “Two alluvial fans had been laid down over the millennia by systems of streams which had coursed from the mountains to the sea during the rainy season, flooding the lowlands almost every year. Topsoil of fine loam thirty to forty feet deep in places overlaid water-bearing substrata of gravels and clays. A. tremendous underground water storage basin with a capacity of roughly one million acre-feet spread itself out beneath this wonderful soil. In many places the water gushed forth from artesian wells. Here was nature’s handsome gift: soils second to none in the state and perhaps the world, indigenous water enough, if properly used, to serve that soil adequately, and a mild climate with a year-round growing season.”

For centuries, this gift of nature was used appreciatively and conservingly by man, first by the Indians who fed off the land, then by Spanish settlers who grazed cattle there, and finally by European immigrant farmers who introduced into the valley grapes and prunes from France, and pear, apricot and other fruit trees. For a time, the valley produced a third of the world’s prunes. Its population of about 150,000 people in the 1920’s and 1930’s divided between those who tended the 100,000 acres of orchards and those who manned the more than 200 food processing plants.

“At this time,” Belser pointed out, “Santa Clara County called itself the ‘Valley of Heart’s Delight.’ It was beautiful, it was a wholesome place to live, and it was one of the fifteen most productive agricultural counties in the United States.”

Although World War II brought many newcomers to Santa Clara’s Moffet Field naval air station and the new electronics firms associated with Stanford and the military, the county grew gradually and relatively smoothly. Its largest towns – San Jose, Santa Clara and Palo Alto – expanded slowly without disturbing much of the agricultural area around them. Their residents enjoyed taking Sunday drives through the orchards when the blossoms were in bloom.

Early in the 1950’s, a book called America’s 50 Best Cities,described the “verdant” valley as “one of the most beautiful in America” and growing San Jose as “a tidy, bustling metropolis of 22 square miles, but still a garden city famed for its liveability, hospitality and healthful climate.” Songwriter Burt Bachrach, later remembering the San Jose of those idyllic days, described in the popular tune, Do You Know the Way to San Jose?, a desire to return to the good life there from the “great big freeway” that is Los Angeles with the now ironic words: “You can really breathe in San Jose; they’ve got a lot of space.”

At that time, there were about 300,000 people living in Santa Clara County. But the valley’s oasis reputation, the pressure of the masses moving south from water-locked San Francisco (quickly filling most of the usable land in San Mateo County between San Francisco and Santa Clara), and the realization that big profits could be made buying and selling the easily developed, unusually flat land on the valley floor combined to set the stage for a rapid change. Soon, 4,000 residents were moving into the valley each month. From 1950 to 1960, Santa Clara County’s population more than doubled to 640,000. By 1970, it exceeded one million people.

“Wild urban growth attacked the valley much as cancer attacks the human body,” remembered Belser, who, as county planning director, was unable to slow or channel that growth. “What so recently had been a beautiful, productive garden was suddenly transformed into an urban anthill.”

Today, the majority of the orchards are gone. The paving and building over of so much absorbent soil has brought about serious flooding of many populated areas during the rainy season, while the heavy demand for water the rest of the year threatens to exhaust the underground supply. The water table has already become so depleted in many places that the land over it is sinking. Meanwhile, the once clear air has been discolored and poisoned by the glut of automobiles and some of the county’s not-so-clean industry (a problem made worse by smog from San Francisco and Oakland blown down the bay into the Santa Clara Valley and trapped there by the mountains).

The cost of borrowing money to bury sewers, pave streets, build schools and provide police, fire and other services so rapidly for so many people spread out over so large an area has put the county and several of its cities deeply into debt and left their new residents facing steeply increasing tax bills. No money is left, for instance, to pay for a mass transit system that could eliminate some of the automobile congestion. The welfare rolls are burgeoning with fruit pickers, packers, canners, and other low paid and otherwise unskilled workers who cannot find work in the county’s new high-powered technical economy. Crime has increased so much in this despoiled Garden of Eden that all of the county’s jails are overcrowded and its officials have asked to borrow space in an under-used facility in neighboring San Mateo County.

Not only have the view of the mountains, the deep green of the orchards and the bright colors of the blossoms almost all disappeared, but little has been done to replace them with usable landscaped parkland amidst all the houses, stores and factories. The most scenic public land left in the valley may be the carefully tended and regularly watered tropical flowering greenery along the shoulders of the several criss-crossing freeways. A private park advertises the availability of its trees and flowers in the local newspaper. It is left to the enclosed, air-conditioned climate, gaudy metal sculpture, coucrete and tile terraces, man-made fountains and brightly colored imitation leather benches of a giant covered mall shopping center to entertain families who once spent their weekends exploring the now lost outdoor excitement of Santa Clara Valley.

Although Santa Clara County undoubtedly was destined sooner or later to be urbanized, the process need not have destroyed the valley as it did. One study has shown that all the county’s growth since 1947 could easily have been fitted into thirty square miles with residential densities no greater than they are now. Instead, because development jumped from here to there and land was used inefficiently, there is a subdivision, factory or shopping center on nearly every one of the valley floor’s approximately 200 square miles of once premium soil. Throughout the county, in some places right in the middle of its cities, are large swatches of vacant, barren, eroding land that were passed over by the developers for one reason or another and are now orphaned from nature by the helter-skelter construction all around them.

On the surface, this wasteful exploitation of the Santa Clara Valley appears illogical and almost inexplicable. But there are important reasons for what happened; Santa Clara’s problems are the logical consequences of a variety of factors. Among them are the economics and methods of get-rich-quick land speculation and development, which are inherently inefficient, wasteful and corrupting. Another important ingredient was the role that government on all levels – city, county, state and federal – played in the process. It was not the role of helpless bystander, but rather that of aide-de-camp, financier and guardian to the speculators who plundered the valley, giving approval and other encouragement to everything that was done. As the Stanford study concluded about San Jose’s growth, Santa Clara is not an “unplanned” suburb, but rather “a misplanned one.”

The governments of Santa Clara County and San Jose (the county’s largest and most influential city with a present population of 450,000) both had the power and expertise to strictly control the speed and quality of development within their borders. Each had a large staff of professional planners charged by local zoning laws with reviewing the developers’ plans for every proposed subdivision, factory and shopping center. Their recommendation on the acceptability of a development proposal had to be approved by the appointed members of the county or city planning commission. And that action was subject to review by the county board of supervisors or the city council.

It was also necessary to win the approval of independent water and sewer district agencies before public money could be spent to extend these necessary utilities to a previously undeveloped area. The state and federal governments decided where new roads and freeways would be built, another essential condition for profitable development. Most new housing projects needed the financial backing of state and federally supervised banks and savings and loan associations, the Federal Housing Administration (and its successor agencies) or the Veterans Administration (in the case of housing sold to qualifying war veterans). Finally, the California legislature went even further and passed other laws designed to protect prime agricultural land and open space like that in the Santa Clara Valley from hasty and wasteful destruction by urban development.

On paper, then, it appeared that the beautiful and useful valley would have been protected during the past two decades by vigilant city, county, state and federal officials armed with broad legal powers. Many of these sentries proved to be less than trustworthy, however, and by 1950 the valley’s protective paper wall was being assaulted and undermined by a variety of pressures.

Developers who looked at the flat valley of spindly fruit trees saw a goldmine. Little investment was needed to clear or level the land for construction. Because the mild climate eliminated the need for basements, concrete slabs could serve as cheap foundations. There also was no necessity for the heavy insulation, strong, expensive roofs and eaves or weather-resistant exterior finishes required in cold winter, snow belt areas. One builder increased profits by substituting cheap flat tar and gravel roofs for the much more expensive conventional peaked and shingled variety, thus acquiring the nickname “Flattop Smith.”

As fast as the builders could put up low-cost, moderately priced tract houses (as well as neighborhoods of quite expensive, custom-built homes), incoming residents snapped them up. Many buyers were primarily sold by the idea of escaping from the crowded city to the open space, mild weather, and greenery they had seen on pleasure drives through the “Valley of Heart’s Delight.” One builder was able to sell 2,000 houses solely on the basis of the valley’s reputation and a model home he put on the roof of Macy’s department store in San Francisco. Few buyers went to inspect the tiny, 5,000-square-foot lots before moving in or envisioned the finished neighborhood of streets packed tightly with the same modern-design but inexpensively built single-level house.

It also happened that just when eager developers were offering farmers $2,000, $3,000 and up per acre for ground that had seemed valuable for farming at $400 to $500 per acre, many farmers were facing serious financial problems. The groves in some parts of the valley were a century old and were due to be torn up and replanted. This expensive process frequently forced farmers to live off their savings or go into debt until the new trees produced profitable harvests. Other orchards were being threatened by an unusual killing fungus that attacked the valley’s pear trees. Many farmers also were pinched by the higher taxable values put on their land after parcels near them sold at comparatively high prices to developers. Their property taxes climbed sharply, and older men feared that death taxes on the higher paper value of their land would make it impossible for heirs to hold onto the land. “Everything,” Karl Belser told me, “worked against saving the land.”

As more and more land changed hands and development spread, driving prices higher and higher, speculation became increasingly popular. Speculators bought land from farmers in still undeveloped areas of the valley and later turned it over to incoming developers at much higher prices. The speculators did not have to do anything with the land themselves or invest much more than a down payment or option fee; they borrowed the rest from a bank or savings and loan. Often they merely signed an option to buy the land at a certain price, allowed the farmer to keep it for a time, and then exercised the option only when a developer came along ready to pay the speculator what amounted to two or three times the option price. The developer, in turn, when building houses on the land, further inflated its price in selling the new homes. This final doubling or tripling of the land value often constituted most of the developer’s real profit.

Thus, land once worth $500 an acre as farmland soon was selling at $3,000 to $5,000 or more to speculators, who sold it for up to $10,000 and more per acre to developers who, in turn, parcelled it out in lots to homebuyers at the rate of at least $15,000 to $20,000 per acre. “It was not unusual,” Belser remembered, “for land to double in price while changing hands in a single day. Everybody wound up speculating in land.”

“Speculating in land” also meant speculating in official zoning and planning decisions. If the zoning of a particular tract could not be changed from agricultural to the desired residential, commercial (for shopping centers) or industrial use, it would still be worth no more than the price it would bring as farmland. The thousands of such decisions to change the zoning of individual parcels of land, with high financial stakes, cumulatively became the turning point for the Santa Clara Valley.

Determined officials could have used their powers to carefully stage the valley’s development, shape it along the lines of some rational master plan and conserve much of the area’s natural assets. A fierce struggle should have occurred between these officials on one side and greedy land speculators and developers on the other.

That battle never took place, however, because there never really were opposing interests. With few exceptions, the local officials were also speculators and developers, or had other vested interests in rapid uncontrolled development of the valley, or simply did not want to take the trouble to make a stand against powerful development interests.

Karl Belser remembered how the pressures were first applied in each case when a developer’s request for a zoning change was brought to the county planning office for review and approval. “Everyday,” Belser told me, “someone would come in and say, ‘Karl, you have to approve this because it’s good for the county.”‘

“Good for the county” meant more money for the county’s developers, realtors and building contractors and subcontractors, as well as more customers for the county’s merchants. Together they contributed heavily year after year to the political campaigns of local officials and financed strong chambers of commerce to promote county growth. This evangelism included hard campaigning to convince confused voters to repeatedly approve bond issues that authorized borrowing money for the water lines, sewers and streets needed for new development. At the same time, the voters were unknowingly mortgaging their homes with the certainty of large future tax bills to pay off those bonds.

One important merchant-booster of headlong county growth was its largest newspaper, the Copley-owned San Jose Mercury. In a quote from a 1965 magazine article that has been widely repeated since, the Mercury’s publisher, asked why he supported uncontrolled county growth despite its destruction of the orchards, replied: “Trees don’t read newspapers.” (Ironically, information from the Mercury’s own clipping files was cited often in both the Nader and Stanford studies of Santa Clara to back up strong criticism of local officials and the Mercury itself. It was shortly after these two studies were released, that I happened to ask the Mercury’s editors for access to those same clipping files. They told me that a new policy closing the newspaper’s library to all outsiders, including reporters from other newspapers, had gone into effect that very day.)

“Good for the county” also meant windfall profits for many of the same local officials charged with making the final decisions on growth for the county. Stanford researchers found from city records and the Mercury library that four of the five members of the important San Jose planning commission were deeply involved financially in the untrammelled county growth during the boom years from 1950 to the early 1960’s. One was a realtor, another a general building contractor, another an electrical contractor, and the fourth a two-time president of the San Jose Merchants Association.

Countless other officials were buying and selling land for speculation. Among those admitting it were an influential Santa Clara County supervisor who was outspoken in his opposition to any government control of county growth, and the controversial city manager of San Jose for two decades, A. P. Hamman.

“They say San Jose is going to become another Los Angeles,” Hamman once testified before a state board. “Believe me, I’m going to do everything in my power to make that come true. ” Again and again in the official annual reports he wrote for the city, beginning in 1950, Hamman emphasized his belief that more and more growth was needed “if San Jose is to fulfill its appointment with destiny.”

Thus, the land developers and those who should have been the land’s protectors merged into a single group exploiting the Santa Clara Valley together. In a widely reported incident several years ago, San Jose officials and various developers were caught meeting regularly in a local hotel for what they called literary meetings. It turned out that they were swapping information about where the next public improvements, zoning and development were to be located. These “book of the month club” meetings, as they came to be called, caused some scandal for a time, but Belser, the Stanford researchers, the Nader group and others interviewed place relatively little emphasis on outright illegal activity as a cause of the county’s problems.

“We believe that less blameworthy motivations have been the cause,” the Stanford researchers wrote. “Human beings tend to sympathize with those with whom they deal… planners, engineers, planning commissioners and councilmen deal daily with people who represent development interests. Advocates of the public interest are rarely seen.”

Santa Clara County’s professional planners were given little in the way of clear cut public policy guidelines for preservation of the valley’s resources in the face of the developers’ insistent demands. A master plan, drawn only after state law required it, consisted primarily of vaguely worded platitudes and loosely mapped suggestions of land uses for various areas in the county. Nevertheless, Belser’s staff, using the plan as best they could to create some order out of the chaos, recommended against many requested zoning changes.

But the planners seldom had the last word. They were often overruled by the planning commission, many members of which were also businessmen with direct financial interests in unimpeded county growth. Nader’s researchers found that the county planning commission’s actions contradicted the general guidelines of the master plan more than 50 percent of the time. Developers who still were not satisfied could and did appeal to the county board of supervisors, who frequently ruled favorably for the developers. Meanwhile, San Jose officials followed almost the same script in making zoning decisions within the city’s limits.

Exasperated with this official complicity, the county’s remaining farmers finally decided to act on their own to stop the developers’ plundering of the orchards. They lobbied successfully for a change in the county’s zoning laws that authorized planners to designate large sections of the county “exclusive agriculture” – putting them off-limits to everyone else. The developers reacted by going to sympathetic Santa Clara cities, whose officials simply annexed and took over all zoning control of areas where developers wanted to build but had not been allowed to by the new county ordinance.

In this way, during Hamman’s twenty years as city manager, San Jose alone annexed hundreds of parcels of land to multiply its land area by more than eight times to 137 square miles. Of course, the developers sought to develop first the cheapest land they could find, which usually was located some distance from the nearest built-up or incorporated area. That fact posed no problem for San Jose, however. It simply annexed whichever street led from its existing outer boundary to the non-contiguous piece of land, along with the parcel itself. As a result, San Jose’s map became an irregular spider web reaching out in all directions with large gaps of unwanted, unincorporated territory left inside it. At one point, San Jose’s boundaries zig-zagged 200 miles to enclose just 20 square miles of incorporated city area. Its old downtown, dating back to Spanish mission days, was lost completely as new spheres of influence created by various far-flung annexations of office building and shopping center sites competed for attention.

In 1955, the county’s farmers tried once more and won in the state legislature approval of a bill to ban further annexation of street corridors and to prevent the takeover of land zoned for agriculture without the approval of its owner. The law did not take effect until 90 days after the close of the legislature, however, which gave San Jose and other Santa Clara cities time to quickly annex everything they could before the other fellow did. This sent residents of areas that did not want to be swallowed up scurrying to incorporate themselves as new cities instead. Seven were soon formed this way, giving the county a total of sixteen cities that wrapped around each other in a confused jig-saw puzzle with no discernible boundaries and little sense of community. To this day, county residents responding to various polls have admitted confusion over just which city or unincorporated county area they live, work, shop or vote in.

As more and more people moved into each city, they created a need for more services and larger government budgets. This need led each city to try to attract still more tax-paying development (even though more development would once again mean more demands on the taxpayers). Builders took advantage of this confusion to shop from city to city comparing differing building codes, lot size restrictions and utility requirements. Usually they picked locations where the requirements were minimal and they were able to invest the least to make the greatest profit. Among the sorry consequences of this system were slipshod construction, wasted land and a general lack of community amenities.

What each city wanted most were industrial plants and retail stores, which pay higher property taxes. In the end, however, they rezoned so much of the valley for industrial use that 3,000 acres of it still stand empty, much of it neglected patches of ground right in the middle of built-up areas. On the other hand, so many stores, small businesses and shopping centers have been built in strips along main traffic arteries in the county that the equivalent of a new strip seventy miles long is added each year.

“This offends more than aesthetic taste,” the Nader report pointed out. “First, it is wasteful in terms of transportation. Businesses are not clustered in available centers for easy pedestrian access after parking. Second, it is wasteful of land. For example, everyone must have more parking facilities to satisfy possible store capacity. More total land must be concretized for parking…than if stores were clustered with one lot serving them all. Third, it is extremely dangerous. Every twenty feet there is a possible entrance or exit from the main thoroughfare.”

“El Camino Real,” the old Spanish road that connected the missions along the California coast and now runs through most of Santa Clara’s major cities, has been transformed into a linear parking lot flanked by strip development. It and so many other old thoroughfares in the county became so congested in this way that it has been necessary to pave over 40 percent of the valley with more streets and parking lots.

Highways and residential streets, along with water lines and sewers, were essential to the development of new areas in the valley; in fact, their location predetermined where and how fast development could spread. And the decision to spend public money for each new road, sewer or water main gave other official bodies – independent water and sewer agencies and state highway officials – still another opportunity to control growth. But they usually used this power merely to service areas where the developers wanted to go next, wherever that might have been, rather than according to some rational plan for the valley’s growth. There was no communication or coordination among county, city, state or these special agency officials and planners before streets were built or pipes laid. Thus, the planners were almost forced to allow development to go where the roads, water and sewers were going anyway. And if, as happened in some places, the sewers were slow to reach some distant location where a developer wanted to build, he was often allowed to proceed anyway, and to construct septic tanks for sewage. For years, human waste from $100,000 homes in the county was disposed of in such septic tanks of doubtful sanitary safety.

But the worst built-in horrors of Santa Clara County were reserved for working-class families of moderate means, even though a surprising amount of new housing was built for them. This could have been an opportunity to extend the American Dream of a decent home to people normally trapped in deteriorating inner city areas vacated by the departing middle class. But to avaricious developers, it was instead an opportunity for easy profits by building especially cheap and flimsy houses on denuded ground for an endless supply of willing moderate-income customers lured to the valley by a false promise of escape. They found themselves duped into buying houses predestined by the hidden poor quality of their construction to become slum dwellings long before their low down payment, “easy terms,” 30-year mortgages were paid off.

Worst of all, it was an agency of the federal government, the Federal Housing Administration, that made the developers’ game work by underwriting those 30-year mortgage loans. FHA was joined in this conspiracy of negligence by local government officials who failed to write and enforce reasonable building codes and other protections against exploitive home building and sales. Each of the several large, sprawling low-cost housing subdivisions put up quickly in the Santa Clara Valley since the mid-1950’s was built and sold entirely with FHA backing. The federal agency guaranteed the low down payment mortgage loans that homebuyers needed to purchase the houses, loans that the nation’s taxpayers would take a loss on every time a disgusted buyer walked away from a house that soon began to fall apart. Federal officials also had the responsibility of reviewing and approving builders’ plans for the subdivisions built and sold with FHA-guaranteed mortgages, and they apparently chose to ignore obvious shortcomings in design and workmanship.

Perhaps the most noticeable consequence of this official negligence is the Tropicana Village development built alongside the freeway to San Francisco in the eastern part of the valley. Its one-story, rectangular box-like houses on concrete slab foundations line streets with such exotic sounding names as Bermuda Way, Sea View, Cathay, Harbor View, Biscayne and Jamaica, though no body of water, palm tree or inviting scenery is anywhere in sight. Like several similar developments constructed then and since in the valley, Tropicana Village was designed as “planned development” and approved under what had been considered a progressive zoning ordinance section giving the developer considerable freedom to depart from normal lot size minimums and other standards. The planners hoped that builders would use the freedom to try new street plans, place stores within walking distance of homes, and provide more parkland and community open space by grouping houses more economically on the land. The developer’s plans also were approved by the Federal Housing Administration, which guaranteed the mortgage loans made to families buying Tropicana Village homes on unusually attractive terms: little or no money down and, in many cases, no payments due on the loan until the home had been occupied for several months. It was promoted as paradise on a budget.

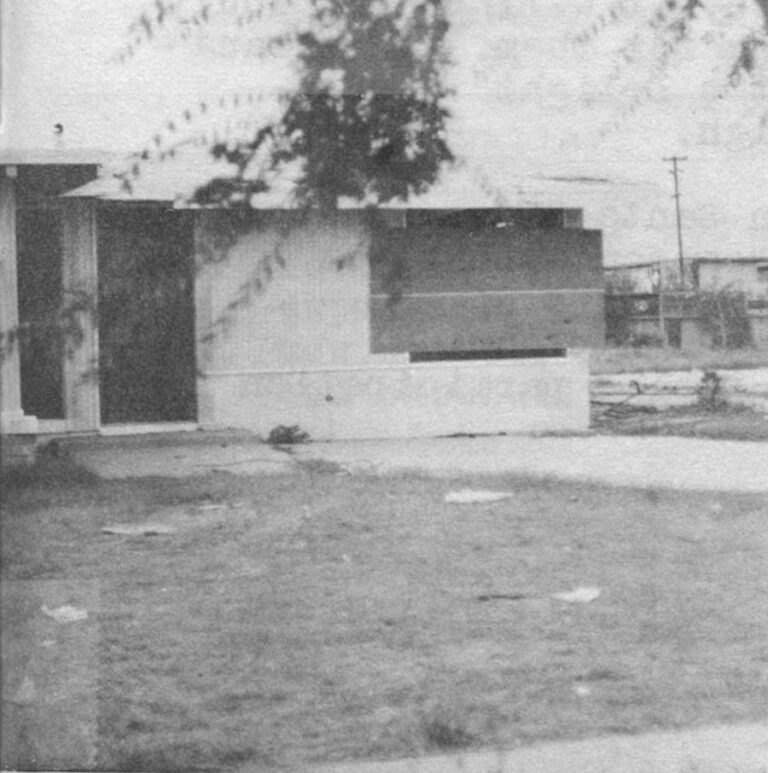

Abandoned houses in Tropicana Village, quickly and cheaply built only ten years ago.

(Note here the empty concrete slabs from which some delapidated houses were removed.)

Today, Tropicana Village is fast becoming a squalid slum in suburbia. The developer took advantage of his release from restrictions to crowd the houses together on small lots, but provided no compensating open space or parks. The shopping center is the usual L-shaped strip of stores around an asphalt parking lot, accessible only by car. The houses themselves are deteriorating so quickly that most occupants cannot afford to maintain them. The cheap, unsightly, low-pitched roofs of tar and gravel have failed to hold up even in Santa Clara’s mild climate. The low quality wood is rotting and the overhanging garage doors are so warped they can no longer be closed. The thin aluminum siding has failed in many places to keep out water that then wears away the cardboard-thin walls inside.

In addition, these insubstantial structures have been repeatedly subjected to flooding each rainy season. Longtime residents of the Santa Clara Valley knew this area flooded annually, and the fact should have been known to federal officials who approved the project, assuming they had been at all diligent in investigating the feasibility of the site. To add to the injury, when the rainy season ends, the “cracking adobe” ground quickly dries, heaves and separates in wide cracks (which didn’t bother the fruit trees) which, in turn, has caused some houses’ shallow concrete slab foundations to crack. When the next rainy season comes, water seeps up through these cracks into the homes.

At the beginning, the flooding so badly damaged some homes that their residents simply abandoned them, turning their backs on their small investment. Since no one else would buy them, the houses were left boarded up or finally demolished, and the federal government, which guaranteed the 30-year mortgage loans on them, had to absorb the loss. The builder had long ago collected all his money when the mortgage loan was made.

There are presently entire blocks of boarded-up houses and empty concrete slabs in Tropicana Village. Across the street, determined working-class families, many of them black or Mexican-American, still struggle to keep their homes in good repair. To a visitor, this task seems all but impossible. For those families who finally decide to move, it will be difficult to sell their houses for what they are paying for them. Tropicana Village is one place in the “Valley of Heart’s Delight” where property values are no longer zooming sky-high.

Both the Nader and Stanford reports on Santa Clara County and the city of San Jose make a number of recommendations for changes in land use planning to salvage what is left of the valley. Among them are suggestions to remove the planning commissions from politics and to facilitate public participation in their deliberations; to permanently zone remaining scenic and prime agricultural areas in the county to prevent future development there; to develop the many by-passed urban tracts before extending development further into the countryside; to buy land with public money where necessary to avoid destructive development; and to rezone the many surplus acres of commercial and industrial land to residential or public uses. There are many other more technical recommendations, all of which appear quite logical. But they simply do not add up to a dynamic program for change. Rather they seem to be more of the kind of bureaucratic tinkering that has been consistently outrun by determined developers and their cronies in government in the past.

Leading Santa Clara citizens acknowledge the problems the valley faces. But too many of them owe too much allegiance to their own municipality or are too preoccupied with their professional and private lives to do more, for instance, than form an ineffectual citizens’ advisory council. They are not facing the valley’s environmental and other development problems as an area-wide emergency that demands an all-out counterattack.

Instead, citizens of such wealthy Santa Clara communities as Los Altos Hills, Campbell and Palo Alto are primarily concerned with trying to build a wall around their communities, to keep the nearby problems of housing for working-class families and the poor or rising crime or commercial congestion from their own doorsteps (even though some, like the polluted air, cannot be stopped at the city limits). They are enforcing strict large-lot “snob” zoning laws to limit their towns to hill estates, gentleman farmer’s ranches and modernistic suburban retreats. Their answer to the problems of poorly planned and controlled development in the valley is no further development at all – at least not where they live.

Meanwhile, the competing large cities of the county, with lower-income residents and huge government debts, are still fighting for more taxable development of any kind, even as new officials at certain levels are talking generally about making improvements. Too many officials and citizens of the county still point to new office buildings, new government complexes, new freeways and the like as signs of progress, although all the old problems remain and intensify. The Nader and Stanford reports caused surprisingly little notice, comment or controversy in the valley.

The time for radical solutions to Santa Clara’s dilemma, however, may be long past. Strong government control of suburban expansion, such as that being tried in England, Scandinavia and now France, or private enterprise attempts at rationally staged and carefully planned suburban satellite “new towns” like Columbia, Maryland, or Reston, Virginia, would have to have been begun ten or twenty years ago. Tinkering just may be all that is left to be tried in the Santa Clara Valley, which is already so very far along in fulfilling “its appointment with destiny.”

Received in New York on November 4, 1971.

©1971 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund Fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, The Washington Post and the Alicia Patterson Fund.