Washington, D.C.

November, 1971

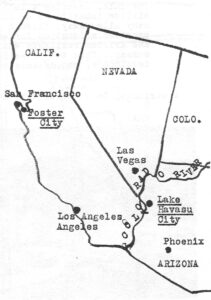

They are the most unlikely of locations: a remote hot, dry Arizona moonscape of dusty, rocky hills and dark, foreboding treeless mountains around a long forgotten reservoir lake on the Colorado River at the California border; and 500 miles away, a once lifeless below-sea-level marsh and salt pond jutting from the San Francisco peninsula into the bay south of San Francisco in teeming San Mateo County, California. On these sites, two of the most audacious, ambitious, highly publicized and personalized versions of the “new town” concept in the United States are being built.

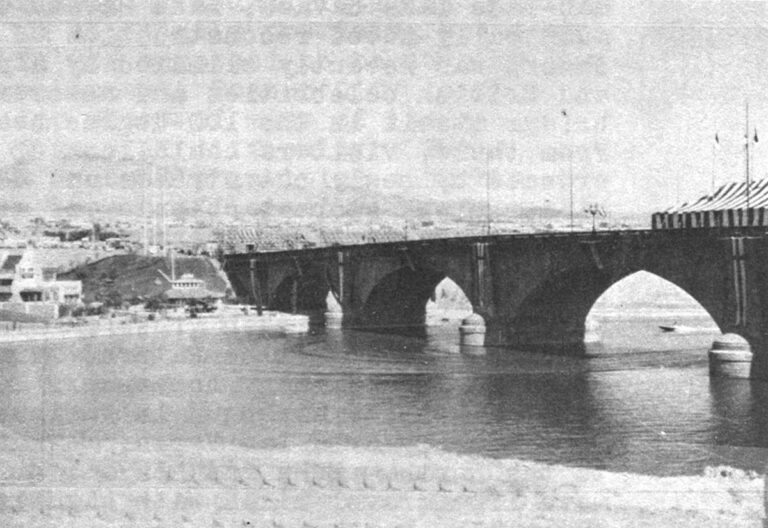

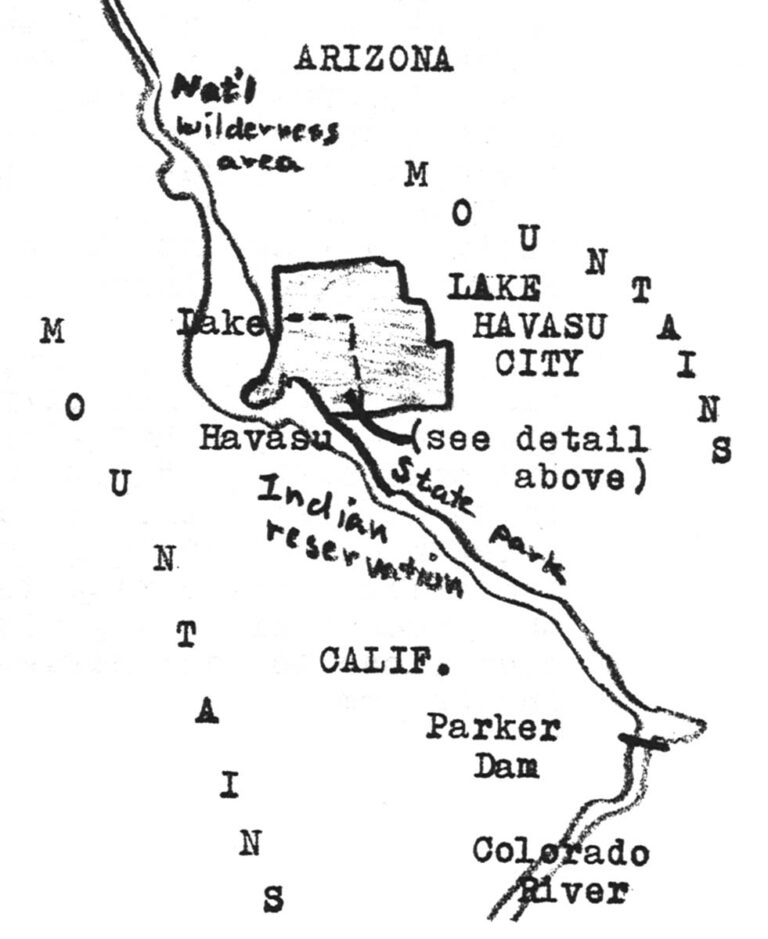

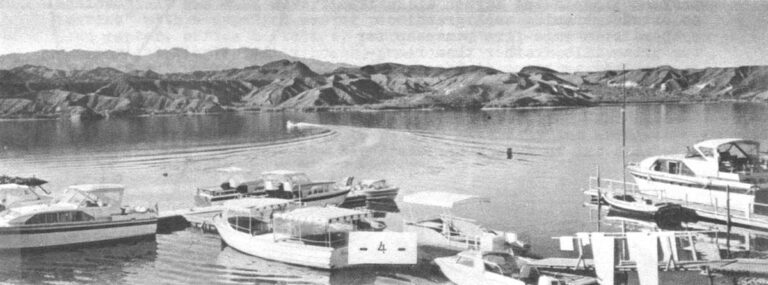

Begun in 1963 on the desolate eastern shore of meandering man-made Lake Havasu, Lake Havasu City, Arizona, is where the much bally-hooed reconstruction of old London Bridge in the desert was recently climaxed by a dedication dinner for American and British celebrities and newsmen in a huge tent atop the bridge itself in the 100-degree heat of an early October Saturday. From there, visitors could look up at desert hillsides criss-crossed by newly cut streets and dotted here and there by houses, cinder block stores, colonies of mobile trailer homes and a clump of factories. There are also golf courses, a small grassy town center circle and some lakeside parkland, all of which has been landscaped with trucked-in palm trees, plants and grass. Nothing but underbrush grows naturally in the area, and the imported flora must be watered twice every day to keep it alive. Because of this, many homeowners fill their “lawns” with brightly painted pebbles arranged in various designs, a fashion imported from equally arid Las Vegas, Nevada, the nearest city, 150 miles to the north. Even the coarse, gray-yellow local sand, which is more like gravel mixed with sizable stones, is unsightly and unuseable, so the newly developed beaches on Lake Havasu are covered with a finer, whiter variety shipped into the desert from the Pacific coast. Eight thousand people live in the new community now, and an increasing number of visitors are being drawn to London Bridge and recreation activities on the lake, attractions greatly magnified by an extensive nationwide publicity campaign. Except for the lake itself, however, Lake Havasu City resembles nothing so much as a spread out, hastily built old West mining town, an accident of history flourishing for a time in the middle of a hot, inhospitable place until the natural course of events turns it into a ghost town and gives it back to the desert.

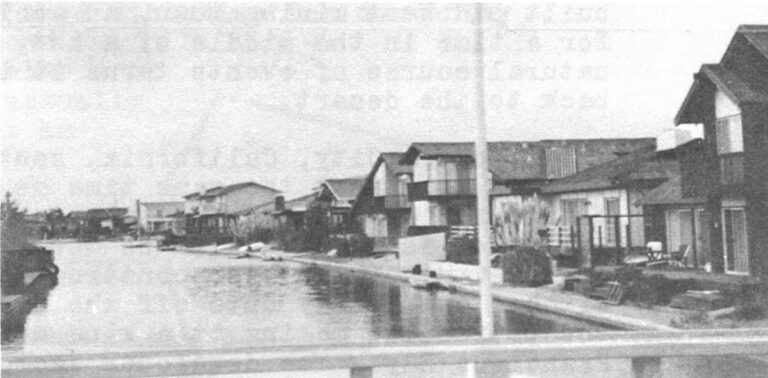

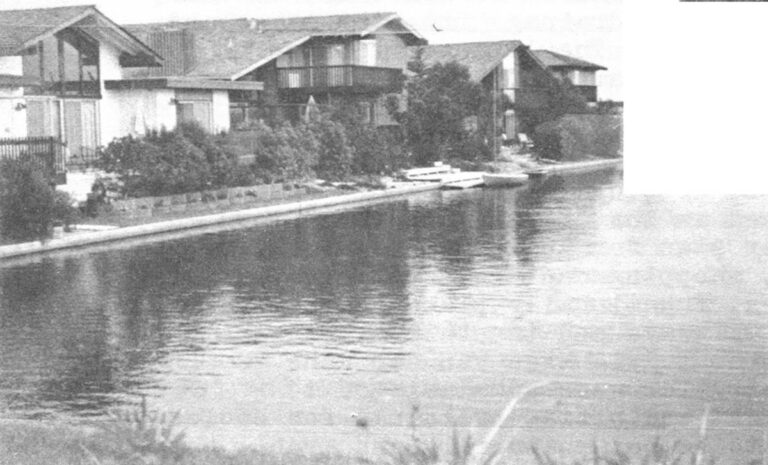

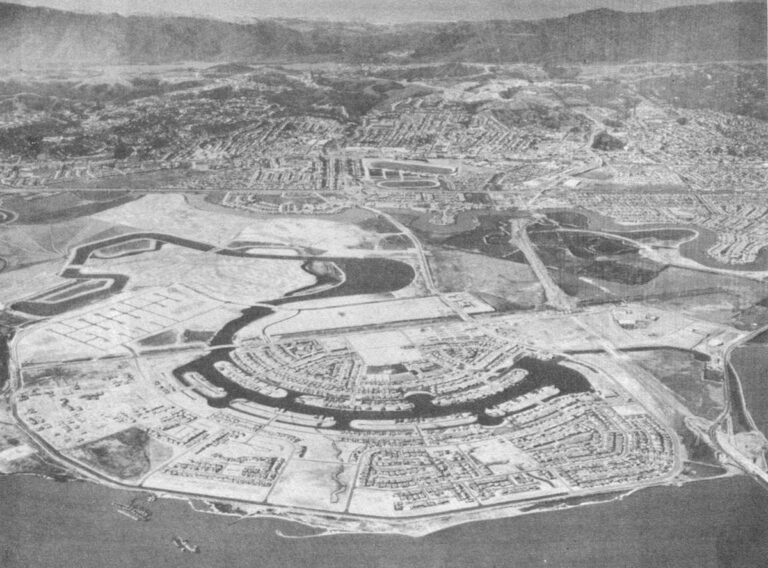

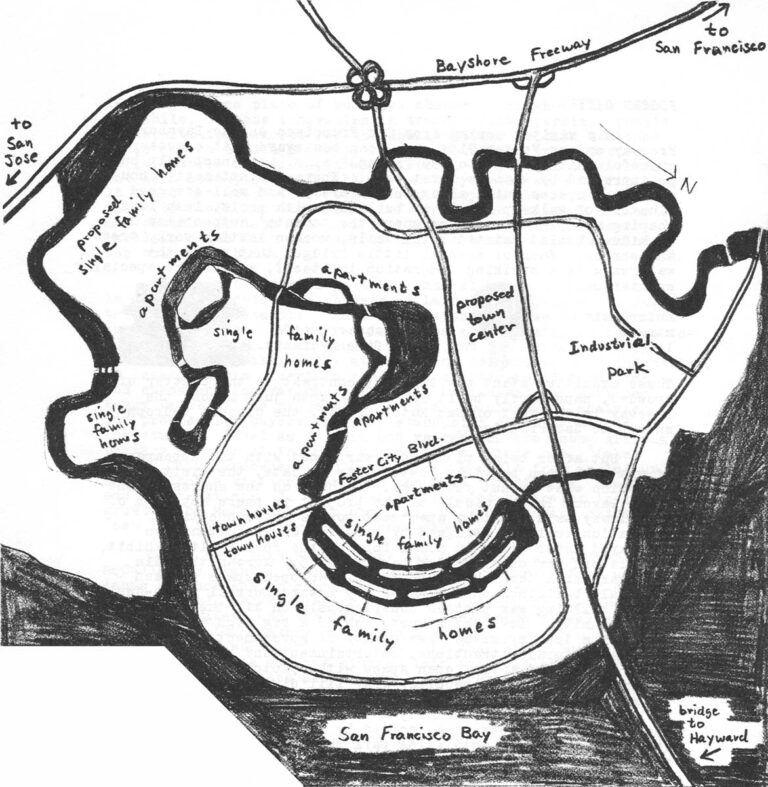

Foster City, California, south of San Francisco, was started at almost the same time as Lake Havasu City, and is also built around and capitalizes on water. In its case, however, the water is in huge ditches used for drainage from the  marshland that is then filled for construction. The largest of these ditches completely cuts off the circular Foster City site from the peninsula, making it a kind of man-made island in the San Francisco Bay. The developer decided to call the ditches “lagoons,” built custom houses and boat docks alongside them, and promoted the whole project as “the island of blue lagoons” and a “new world Venice.” It was also advertised as the “first actual new town in America” with a detailed master plan for an industrial park, a town center, office buildings, shopping centers, apartment buildings, substantial single-family homes, functionally planned streets, recreational parks, greenbelt walkways and innovative schools. Such world-renowned architects as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Edward Durrell Stone and Le Corbusier were commissioned to design heroic high-rise apartment and office buildings for choice sites in a community that was to be both naturally and architecturally picturesque. The San Francisco Museum of Art displayed plans and scale models of the project in a month-long exhibition called “Design of a City: Foster City.” Journalists and planners across the country hailed it as an especially promising new town endeavor. Today, however, when it was supposed to be nearing the end of its planned eight-year development, Foster City is only partially completed, has fallen far short of many of its goals, and is mired in controversy and financial difficulty. The finished places in it comprise an unusually inviting suburban community, with well-built modern houses efficiently arranged on pleasant streets, particularly attractive apartment buildings with hidden auto parking, scenic waterways and parks, and uniquely designed road bridges, lampposts and even fire hydrants. However, Foster City has little industry, no town center, few of the striking designer buildings shown on the museum models, no cultural activity or entertainment, nobody but middle-middle class residents, and none of the city-like characteristics promised in the grand plans. Its schools are overcrowded. The lagoon water is polluted. The community is burdened with a gigantic public debt. Despite its problems, it is still a place where many of its 13,000 suburban-minded, commuting residents are quite happy to live, and where property values continue to appreciate, partly because it is so close to San Francisco. But Foster City today can hardly be considered a viable new town.

marshland that is then filled for construction. The largest of these ditches completely cuts off the circular Foster City site from the peninsula, making it a kind of man-made island in the San Francisco Bay. The developer decided to call the ditches “lagoons,” built custom houses and boat docks alongside them, and promoted the whole project as “the island of blue lagoons” and a “new world Venice.” It was also advertised as the “first actual new town in America” with a detailed master plan for an industrial park, a town center, office buildings, shopping centers, apartment buildings, substantial single-family homes, functionally planned streets, recreational parks, greenbelt walkways and innovative schools. Such world-renowned architects as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Edward Durrell Stone and Le Corbusier were commissioned to design heroic high-rise apartment and office buildings for choice sites in a community that was to be both naturally and architecturally picturesque. The San Francisco Museum of Art displayed plans and scale models of the project in a month-long exhibition called “Design of a City: Foster City.” Journalists and planners across the country hailed it as an especially promising new town endeavor. Today, however, when it was supposed to be nearing the end of its planned eight-year development, Foster City is only partially completed, has fallen far short of many of its goals, and is mired in controversy and financial difficulty. The finished places in it comprise an unusually inviting suburban community, with well-built modern houses efficiently arranged on pleasant streets, particularly attractive apartment buildings with hidden auto parking, scenic waterways and parks, and uniquely designed road bridges, lampposts and even fire hydrants. However, Foster City has little industry, no town center, few of the striking designer buildings shown on the museum models, no cultural activity or entertainment, nobody but middle-middle class residents, and none of the city-like characteristics promised in the grand plans. Its schools are overcrowded. The lagoon water is polluted. The community is burdened with a gigantic public debt. Despite its problems, it is still a place where many of its 13,000 suburban-minded, commuting residents are quite happy to live, and where property values continue to appreciate, partly because it is so close to San Francisco. But Foster City today can hardly be considered a viable new town.

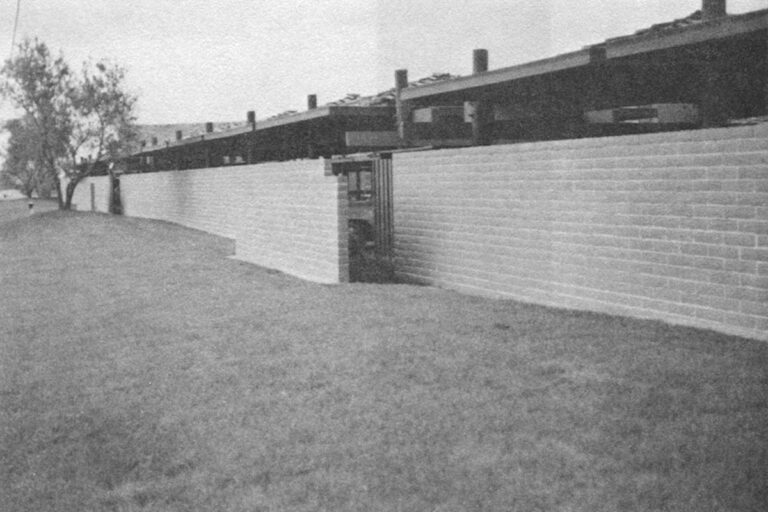

Attractive waterside homes at Foster City, California, “the island of blue lagoons.” The houses are yet to be joined by planned industry, shopping and town center that were to be built long ago in this attractive but incomplete and financially ailing new town project.

It and Lake Havasu City have much in common. Each is the highly individualized embodiment of an ambitious millionaire’s vision. Each began by testing a different new town theory on land that might never have been used otherwise for community construction, or any other purpose. Although each has achieved certain qualified successes, both were actually doomed from the start to failure as realistic, innovative new town projects by built-in fatal flaws, some of which are endemic to nearly all speculative real estate ventures. A cursory examination of the two projects’ strengths and weaknesses should tell us much about the prospects for success of other new town experiments in the United States, as well as, one hopes, help prevent experts and laymen alike from so often embracing such grandiose proposals as sure-fire panaceas for our urban ills, rather than recognizing them as being at base crafty schemes for quick personal aggrandisement and monumental image building.

Lake Havasu City

“The shade is moving,” remarked a visitor to Lake Havasu City during the heat wave that accompanied “Dedication Weekend” in October for the reconstructed London Bridge. A nearby palm tree had just been yanked out of the ground and was being carried away by a machine that combined the abilities of shovel, crane and front-end loader. Several trees, in fact, were being moved from a cluster of buildings that housed construction firm officials several hundred yards away to each end of the bridge, where landscaping was being hastily completed for the next day’s ceremonies. The palms were being grouped in small tropical gardens, a bizarre juxtaposition with the facimile London city street complete with pub that was under construction at the base of the bridge. The waterway under London Bridge is also man-made (it is a channel cut across a small peninsula) as is, of course, Lake Havasu itself. The lake, whose name means “blue water” in an Indian language, was created in 1938 when the Parker Dam on the Colorado River was finished. Without it, the site would still be desert – unattractive desert of little interest to anyone.

The promotional literature for Lake Havasu City begins by stressing the presence of so much water in a place where rain seldom falls. “Water is the story of Lake Havasu City,” the brochure tells us, “water in such abundance it is hard to imagine.” The lake, covering a total area of 39 square miles, serves 10 million inhabitants of central and coastal southern California, many miles away, through the Colorado River Aquaduct. It also provides a location for water recreation for the many California and Arizona residents who eagerly seek out such oases each hot summer. This too is well exploited by Lake Havasu City’s developers, who dreamed up such events as the “Lake Havasu City Outboard World Championships,” “Lake Havasu City National Ski Championships,” “Lake Havasu City Desert Regatta,” and now, the annual “London Bridge Channel Swim.”

It all adds up to one of the greatest promotional buildups since the exhibition tour of the Cardiff Giant. What’s more, this escapist, promotional atmosphere is the driving force of Lake Havasu City. Attracting more and more people, and more and more money, to an artificial oasis in the middle of the desert – 350 miles from Los Angeles to the west and 250 miles from Phoenix to the southeast – is the central purpose of the project and the plans made for it by its founder, Robert McCulloch, millionaire manufacturer of chain saws, power boat motors, snowmobiles and small airplanes (not to mention his oil wells and other real estate ventures, primarily vacation communities.)

Besides the steady profits he has realized from his many business enterprises, McCulloch made a brilliant land investment when he bought ground inexpensively in western Los Angeles many years ago for his first factories. The land is now worth many times what he paid, and McCulloch saw a chance to cash in by moving his base of operations. He chose the Lake Havasu site after discovering it from the air during a flight to Los Angeles from Las Vegas. He tried out the lake as a testing place for his outboard motors, and then bought the only city-sized parcel of land available – 16,500 acres – at a public auction from the state of Arizona. Much of the land around the lake had already been set aside for state parks and a federal wildlife preserve.

McCulloch moved some of his factories to the new site and began building a town there, a town that would be guaranteed rapid initial growth by the influx of McCulloch employees and the advantages of Lake Havasu. He jumped at the chance to increase its attractiveness to tourists when old London Bridge was put up for sale by the British, who are replacing it with a new span across the Thames. McCulloch bought the 1,000-foot long, 13,000-ton bridge for $2.5 million, and paid another $8 million to have it shipped by boat and truck in 10,246 numbered pieces to Lake Havasu City for reassembly. One of the designers of Disneyland is now supervising construction of a $1.2 million English village at the base of the bridge, which is to be later expanded into a large “British Crown Colonies” resort park.

That same designer, Robert Wood, also drew up the master plan for Lake Havasu City, a plan which McCulloch said would produce a city “that will be self-sufficient and beautiful.” And self-sufficient it must be, because it stands all alone in the desert. Only a few small firms, including a printing concern and a trucking warehouse, have joined McCulloch’s own factories there during the past eight years. He is now in the process of moving almost all the rest of his Los Angeles operations to Lake Havasu to give its economy another shot in the arm.

Yet Lake Havasu City remains too small to be completely self-sufficient. If a resident becomes seriously ill, he must travel to the larger town of Kingman, Arizona, sixty miles away, to receive hospital treatment. Department stores are much farther away, in Phoenix. Lake Havasu City still has no cemetary, and several recently deceased residents have been temporarily buried in Kingman. Residents complain about the shortage of such skilled workmen as auto mechanics, and the town’s first veterinarian and obstetrician moved in not long ago, welcomed by jubilant large-type headlines in the weekly newspaper.

It is precisely lake Havasu City’s isolation, however, and its attempt at a kind of resettlement of industry and population away from California’s big cities into the desert that provides the best argument for its being a bona fide new town. Creation of many such new communities far from the edge of existing creeping urban sprawl has been urged by many planners and government groups. But they also expected that any such projects would pioneer better ways of urban living in their fresh starts. Lake Havasu City is not doing that. Instead, it is already well on its way to becoming another Los Angeles in miniature.

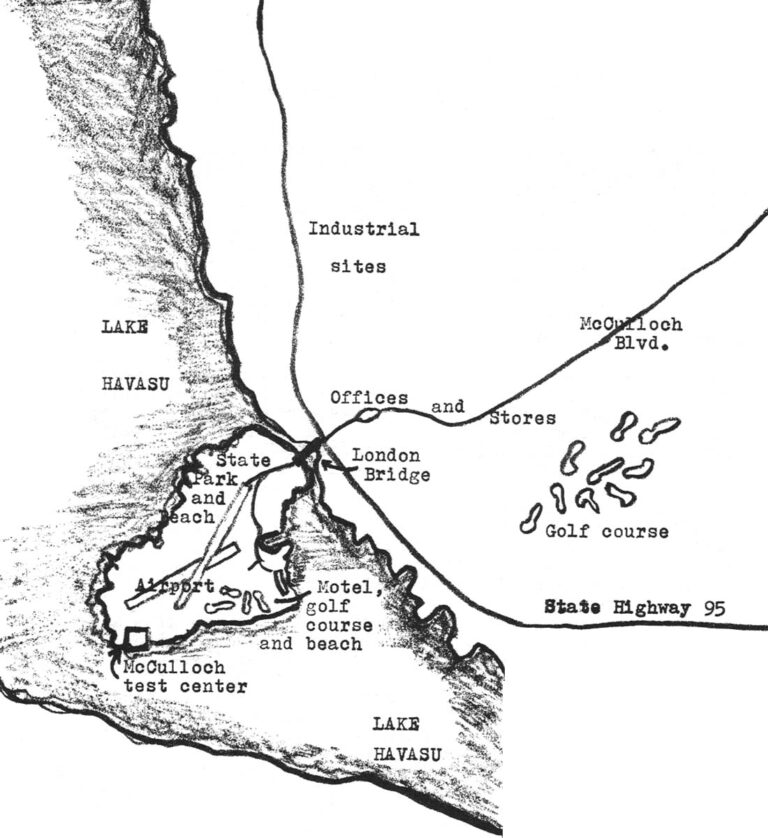

Its master plan, far from projecting a model community that would be “the prototype for future developments,” as McCulloch’s publicists proclaimed (and many writers have echoed without seeing the town), is a plan only for maximizing returns on the real estate investment dollar there. The town’s industry is grouped with the mobile home colonies that still house the majority of its employees behind a hill, out of sight of the residential areas. Building heights are limited to protect a view of the lake from almost any home, apartment or motel room. The big motels and golf course, and the expensive golf course homesites, were given the choicest spots of all. Beaches, campgrounds, another motel complex, boat docks, and an airport for McCulloch’s airline were placed on the flat peninsula that became an island in the lake when the London Bridge channel was dug. And McCulloch’s name was put on the gas-lit boulevard that runs through the middle of town and over London Bridge to the island. That, for all practical purposes, was the extent of the planning.

Lake Havasu City map: Except for concentrations of activities noted here, housing, stores and schools are scattered widely throughout the town site, which, as shown on map at right is all alone in Colorado River valley, surrounded by areas designated as state parks and national wilderness areas, Indian reservations, and mountains, all quite arid and barren.

The rest seems to have just happened. Stores in Lake Havasu City have sprung up all over the place, especially in traffic-jamming strips along the main arteries. The architecture ranges from uninspiring to ugly. Housing is so widely spread out that it is bound to make the cost of city services steep in the future. In many places, to make it possible for anyone with the money and interest to buy a lot wherever he liked, the developers, using tax money, simply paved an otherwise empty street out to the most distant house on its path. Such gimmickry as a two-story cardboard replica of the London Tower in front of one place of business abounds throughout the town. Meanwhile, not one innovation in traffic flow, parking, public transportation (except for the double-decker British bus that rolls across London Bridge), housing construction, shopping malls, public buildings, trash disposal or pollution prevention has been attempted. If Lake Havasu City ever were to fill up, it could be expected to suffer from every single urban problem that its residents supposedly left behind in existing cities and towns. Perhaps the families that built their new desert paradise homes with bars across all the windows are planning for this possibility.

It is not surprising, then, that although the publicity is all about prototypes, buyers at Lake Havasu City are being told about investments. Their attention is drawn to how scarce such fresh water lake recreation sites are becoming in the southwest, how many tourists London Bridge and its surrounding old English resort likely will attract, and how McCulloch’s industries, at least, ensure a certain reservoir of year-round inhabitants and customers for various new retail businesses and services. Every facet of the project, present and planned, is analyzed for prospective buyers from the standpoint of being a good investment. “Just as tourism and recreation are among Arizona’s primary sources of income,” one brochure points out, Lake Havasu City landowners and businessmen benefit from an influx of profitable visitors” who use the lake for fishing, boating and water-skiing. “…Those with foresight to invest in this growth” (of McCulloch’s industries), another passage extols, “can look toward being richly rewarded.”

Thus far, Lake Havasu City has attracted workers at McCulloch’s plants, families and retirees escaping from winter (some of whom end up complaining about the constant 100-degree summer heat), others fleeing congested cities for the open space and water, and the investors. They operate real estate offices on almost every corner on one stretch of McCulloch Boulevard, or work for one of the more than sixty building contractors. One man has plunged into the real estate, grocery and souvenir business all at once, talks optimistically about the money to be made, and enjoys a posh home next to the hilltop golf course.

A retired woman who lived for a time with her son in Lake Havasu City before moving further west to San Diego, said most of the people she met there were “losers looking for a last chance to get ahead.” For all these people, Lake Havasu City serves a purpose, and does not appear to be a waste of the barren land on which it is being built. But for that same reason, it is clearly a one-of-a-kind place – be it recreation community, tourist trap, real estate investment or ultimate escape – and it certainly is not a new town model to be copied elsewhere or studied for solutions to urban problems.

Foster City

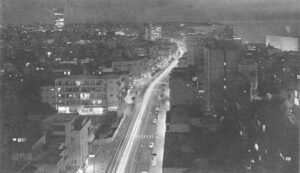

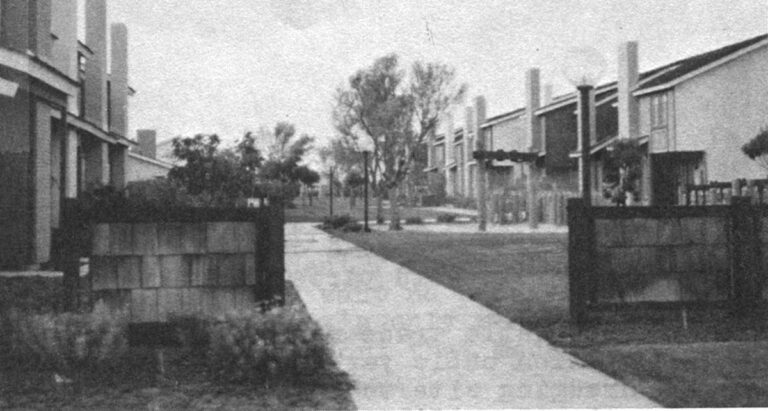

As a visitor coming from San Francisco on the Bayshore Freeway enters Foster City on it a long boulevard that crosses a graceful white bridge to the “island” site, he cannot help but be impressed by what he first sees. There are attractive houses and green spaces built along the waterways and well-designed clusters of walk-up apartment buildings with pools, lush landscaping and places outdoors where the tenants’ automobiles can be hidden behind painted brick walls, wooden lattice work, trees and shrubs. Each of several little bridges that cross the waterways is a striking decoration in itself, as are the specially commissioned futuristic street lamps and small squared-off fire hydrants.

These amenities stand out in sharp contrast to the clutter of crowded, haphazardly built suburban tracts just across the freeway in the rest of San Mateo County, the closest bedroom suburb to San Francisco.

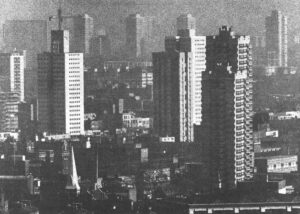

But after being pleasantly surprised with the appearance of what has been built in Foster City to date, the visitor begins to notice what is not yet there. Nowhere on the shores of the large lagoon in the middle of the project is there any sign of the glassy twin 22-story apartment towers and connecting recreation building designed by Mies van der Rohe that was displayed under glass in model form at the Foster City exhibit, and planned for construction back in 1965. Across the main boulevard from the lake there is only an open space between two small buildings where a 14-story Edward Durrell Stone-designed office building was plotted conspicuously on all the models of the community. Down the street, behind a big sign marking the spot for a long promised town center of government buildings, stores, cultural attractions, entertainment and pedestrian malls, there is instead a vast open space with splotches of browned, untended grass in the peculiar gray fill dirt dredged from the bottom of the bay. Out Foster Boulevard, where similar signs mark the site of the community’s industrial park, there is another largely empty area, dotted by a few small firms. Missing from here is a huge auto sales park that was to have been built years ago. A drive around the entire 2600-acre city site turns up only one small shopping center with a grocery store, a few small shops, and a restaurant that is open only at night. In all of Foster City, in fact, no place could be found for a visitor to buy lunch.

There are also hidden deficiencies in the Foster City project. Its residents still must pay off, through local taxes, more than $64 million in bonds sold by the developer to finance the giant landfill operation needed to raise the overall level of the site by four feet, which even then did not comply with existing state regulations. They and other San Mateo county residents also must bear an unusually heavy tax burden to support Foster City’s schools, because there is too little industry and retail commerce in the project to help foot the bill. Because of this imbalance, San Mateo taxpayers have been slow to vote for new school projects in Foster City, which has produced serious overcrowding of otherwise excellent schools. Finally, Foster City residents have been warned by some experts that the next massive earthquake in the area, expected by most geologists before the end of the century, could rupture the 84-foot dikes that now keep the bay waters from inundating the entire site.

The first dikes were built there seventy years ago when rancher Thomas Brewer used the tidal salt marsh to graze cattle. In the 1920’s “Brewer’s Island” was bought by the Leslie Salt Company and other investors, primarily for its value as a salt reserve. They apparently could not conceive of a way to build housing on the property, even though all of San Mateo County around it was being rapidly transformed into a convenient bedroom for San Francisco workers. By 1960, however, millionaire developer T. Jack Foster, with help from a local real estate entrepreneur and an accountant, was able to devise a clever scheme for exploiting Brewer Island’s enviable location. They planned to dredge sand and mud from the bottom of the San Francisco Bay to raise the level of the site, build bigger dikes, and channel the drainage from the land into scenic lagoons spotted with man-made residential islands. They planned to pay for this unprecedented American land reclamation – as well as the construction of roads, sewers and other improvements – with bonds they would be empowered to issue by forming a special improvement district.

Under California law, special improvement districts, like cities, could sell tax-exempt bonds which would eventually be repaid by taxes from the district’s residents and landowners. But in the past, such districts had usually been set up for the reclamation or irrigation of lands to be used for agriculture or recreation. Never before had this power been used to finance so expensive a project as Foster City, and Governor Pat Brown at first balked at the idea. However, because it had the unanimous backing of the legislature and the San Mateo County supervisors, he set up the Estero Municipal Improvement District for Foster City.

Foster City: the small man-made island in the San Francisco Bay (middle and top map), and, turned around to match view in large photo on facing page, a view of its plan (below).

The legislature and the county commissioners had acted before fully realizing just what this new entity really would be. All they had seen were the grand plans presented by Foster, a highly successful builder of homes and hotels in Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and Hawaii. Once the project became wide public knowledge, however, some San Mateo citizens and officials began to ask questions. Who would pay for schools for the 35,000 people due to move in so quickly, if Foster City did not attract all the industry it promised? Was not the site in danger of flooding in the event of an earthquake? Was it not in the flight path of the nearby San Francisco International Airport? Just how realistic was this landfill and bond floating scheme?

But by then the special district had been formed and Foster City’s special zoning granted. As the largest landowner in the district, Foster controlled a majority of the Estero district’s board of appointed members, and they voted to float bonds to pay for the dredging and filling operation, roads, sewers, water mains, burying of utility lines, planning and advertising the community’s development, and even for payment of the interest on bonds already sold. This relieved Foster of nearly all the usual costs that must be borne by a developer, at the expense of future taxpayers. He merely sold parcels of land at big profits to home builders.

While trade magazines extolled the mass movement of 18 million cubic yards of fill more than two miles from the bay dredging site to Foster City, the Estero district’s debt climbed swiftly until it was the largest for the assessed value of the land in the area. Foster City homebuyers weren’t being told about it, but they would have to pay that debt off with their taxes in the future.

Finally, after a few years had gone by and the dredging operation was about three-fourths finished, one homeowner discovered the details of the mounting public debt, as well as the fact that he could never take title to the lagoon island land on which his home stood (a leasehold gimmick designed to keep for Foster title to enough land to control the Estero district for as long as necessary). The homeowner went to court, and the dredging and filling operation was temporarily halted. Foster’s company finally prevailed in the appellate courts after a long fight. But by that time the dredging had been stopped for too long; industry and some big builders were afraid to get involved in the taxing and legal tangles. Foster himself was dying of cancer, and public pressure had been brought to bear on the state legislature to amend the special district law. The legislature finally acted to make the Estero district a resident-controlled body, which promptly shifted some of the district’s tax burden from homeowners to Foster’s firm.

The resulting financial and public relations problems prevented construction of the model high-rise office and apartment buildings, the town center, and the various planned shopping centers, or the filling of the industrial park. The fears of the early naysayers were realized: an unfinished community, overcrowded schools, high taxes, an airplane noise problem that forced citizens to band together to demand higher takeoff and land trajectories for the airport, and a still unsettled debate over what calamity may befall the community when the inevitable earthquake occurs. After Foster died, his sons systematically sold off most of the undeveloped areas of Foster City. Housing demand so near to San Francisco remained so great that homebuilders picked up many lots. Boise-Cascade bought the industrial park and is hard at work promoting it. And Centex, a giant Dallas-based builder, took the rest, including large chunks of land that still must be filled.

There is no doubt that remaining sections of Foster City will be developed somehow. Population pressures, inflation, and the undeniable attractiveness of the completed parts of the project assure the community of some economic viability, despite all its problems. But how it will be completed is now anybody’s guess. The grand architecture and vibrant, self-contained city-like atmosphere promised in the early days of the project may never be realized. Its residents who recently incorporated themselves as a city, have made it clear they want no housing there for low income families. And the project’s only real innovation is the controversial reclamation effort that made construction there possible.

Foster City probably will survive as a Sunday real estate section picture suburb for middle class residents willing to pay higher taxes for the location, with some “clean” industry and commercial facilities. But it will never buy any kind of urban development laboratory or new town, no matter what anyone may have been told to the contrary by the promoters.

In fact, both Foster City and Lake Havasu City should remain of interest only as particularly good examples of how ambitious real estate promoters can go after the same old fast buck in a new way by claiming to be building new towns.

Received in New York on November 23, 1971

©1971 Leonard Downie, Jr.

Leonard Downie, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Fund fellow on leave from The Washington Post. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Downie, The Washington Post and The Alicia Patterson Fund.