As I walked down the corridor, I checked my watch. It was past ten a.m., which left me no more than half an hour to spend with twenty-two year old Bette Glassman. During this time Bette and I would share, for the most part, the sad bath of her silence-though sometimes she did sigh, did offer an occasional comment, which in itself seemed to bubble up from far below the surface, like a communication from a submerged submarine. We had, it’s true, exchanged almost two whole paragraphs on the subject of the research on “women and depression” that I was doing. But this had been over a week ago. The flame of her interest had sputtered rapidly, been doused by a wave of feeling arising from somewhere within. She’d lapsed into her customary apathy, her quiet. Now, the main thing that she managed to communicate to me-and this, unfailingly-was that she expected to see me the following day; and that I must let her know if I wasn’t planning to come.

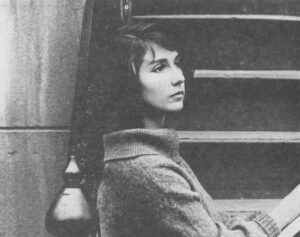

Bette had been on the ward for about two weeks. She’d been brought in mute, white-faced, withdrawn-by her frantic, almost hysterical parents. The daughter of a fairly well to do businessman, the graduate of an Ivy League college, Bette had a good job as an assistant buyer in the sportswear department of one of the major Boston women’s stores. She was twenty-two years old and her credentials, on paper, were those of an independent, autonomous young woman. But in some deep and awful sense, she’d never really managed to leave home.

Bette had been on the ward for about two weeks. She’d been brought in mute, white-faced, withdrawn-by her frantic, almost hysterical parents. The daughter of a fairly well to do businessman, the graduate of an Ivy League college, Bette had a good job as an assistant buyer in the sportswear department of one of the major Boston women’s stores. She was twenty-two years old and her credentials, on paper, were those of an independent, autonomous young woman. But in some deep and awful sense, she’d never really managed to leave home.

The story, as the staff had managed to piece it together, was that Bette, an only child, had been with her parents for a weekend visit when events had taken the deadly turn that was to end in her hospitalization. It had started, almost ludicrously, as a quarrel about whether or not she should he permitted to keep-to balance and maintain, that is-her own checking account! Mrs. Glassman had asserted that Bette, when she wasn’t forwarding her statement and checks home to be balanced, continually overdrew her fund: the daughter had countered, reasonably enough, that it was her money and her right to make mistakes with it if she would. Her father had observed, then, that on the two previous occasions when she’d been permitted to keep the checking account herself, she had overdrawn the account…and this discussion had escalated into a violent quarrel.

What, I wondered, did Bette’s keeping her own checks mean-in fantasy-to each one of them? Was it the end of mutual dependence, a real separation, the end of everything they had in her childhood-the end of love, control, or what? The wild words had, in any case, culminated in a mixture of tears and fury, in Bette’s leaping up from the dining room table, in her fleeing to her bedroom and slamming her door so hard that, in her mother’s words, “the entire house shook.” In her crying and sobbing and moaning, endlessly, refusing to let them come in…and so most of the night passed. The next day the storm was over. Her bedroom door was unlocked, and Bette silent. She’d remained that way, in her bed, curled up in a fetal position. The weekend had slid by but still she’d refused to get up, to go back to work, to leave. She’d simply remained there, silent and blank-eyed, staring at the narrow vertical design of the pale rose wallpaper. She was uncanny, frightening, the very parody of the dependent child…a fetus.

She had been like that, as much as she could be, during her first days on the ward. As soon as any possibility for doing so presented itself, Bette had retreated to her room, curled up, dressed or in her nightgown, lay there under the covers looking, as her father said, “like a dead baby.” To be around her, to sit with her, was to breathe in the stagnant, hopeless, dead-end quality of her despair. But just recently, as had been noted with satisfaction at the early-morning Ward Rounds, she’d been becoming progressively more communicative. She was, though still relatively silent, growing more approachable, according to all reports. She was answering questions with a full phrase, or even a sentence, rather than a grudging monosyllable. Either the medication, or her relations with the other patients and with the staff members, were helping. She wasn’t better yet; on this everyone agreed. But she was, in some subtle way, improving.

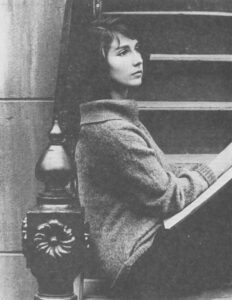

This morning, to my surprise, I found Bette sitting on the edge of her bed. She was dressed in jeans and a ski sweater; she’d just lit a cigarette, and, blowing out the match, she laid it in a bed table ashtray. Her legs were idly swinging. When I asked how she was feeling, she shrugged, began-to my surprise-complaining volubly about her parents: “Here I am, a college graduate with a responsible job-a damned hard and demanding job-and I’m not even allowed to keep my own checking account!” There were two pink spots on her cheeks, signs of life that I’d never seen there previously; she was angry. I told her how much better she looked, and this was true. The change, even from the day before, was Lazarus-like; she seemed returned from the emotional dead.

She had more words at her command, today, than I’d ever imagined she would have. We spent the next half-hour in what was, amazingly, a conversation. We talked about the absurdity of the situation, of the money being her money, earned by her own labor, and therefore her own to take charge of. Why shouldn’t she be able to make mistakes with it, to overdraw her account if she were careless-to control what was, after all, her own? And how was it, I was speculating, that a petty conflict such as this one had required resolution on a psychiatric ward?

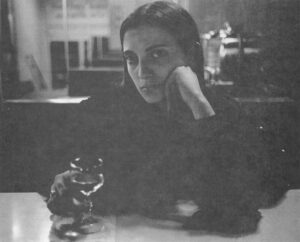

Bette, secure in my agreement with her view of the situation, was busily erupting in hot gusts of feeling; I was, I think, merely nodding my head, encouraging her to continue. But then, having presented her side, her arguments, her own position about the bank account, she suddenly ran down, ran out of steam, looked at me uncertainly. She looked like a frightened kid. “Of course my mom is much better at adding figures than I am,” she admitted. “I mean, I honestly did make the holiest mess of my bank account when I was keeping it…” I blinked, stared at her. I wasn’t sure whether or not Bette comprehended the leap, the huge emotional turnabout she’d just accomplished.

I was so surprised that I said nothing. I felt, however, the cloud of humid sadness settling over us. The high color had vanished from Bette’s cheeks; she seemed, on the instant, drained of life and energy…the person I’d known her to be, before today. But she answered as if I had, in fact, asked her the questions starting to develop in my own mind: “My parents and I,” she said quietly, almost as if she were whispering the information to herself, “are…somehow…locked in a death embrace. My mother, mostly: she needs to control me, and I-for some reason-need to come back to them, to her, and be controlled. Sometimes I feel as if I’m being pulled back home almost physically…As if I’m at the end of a long, invisible string, of a yo-yo.”

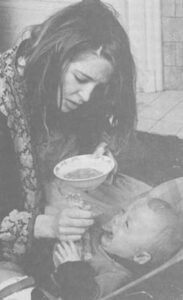

Bette described her experience of herself as “pulled back, as if by an invisible string” into the web of her earliest relations and into that most primitive of human bonds, the child’s tie to his or her caretakers. This is, truly, the first love of any individual’s existence. And what we call the first love or first awakening of adolescence isn’t so much an awakening as it is a reawakening-of intense passions, first experienced beyond the reach of conscious memory and buried now, for the most part, in the distant, distorted, dreamlike world of infancy.

It was of course Freud who first drew attention to the potency and force of this early infantile love-attachment-and to its grave significance for later psychological and sexual development. In a way this first love is an apprenticeship and a model for later love relations, the love-bonds formed in adulthood: And “The Way It Was” in this crucial first experience of emotional bonding can provide so deeply ingrained a pattern- for-loving that the person, almost mesmerically, constructs and reconstructs the family romance over and over, throughout a lifetime. Among the women that I’ve interviewed I’ve seen many who-almost trance-like in their behavior-have replaced a remote and unreachable parent with a remote and unreachable spouse. Parent and spouse may seem, on the surface, to be totally different kinds of people. But for the woman in that love relationship the emotional climate is the same.

That we should repeat this first experience of loving in many forms and guises later on in life isn’t, however, something really very surprising… not when one thinks about it. Our basic training for the important business of loving does occur in this particular context-in this earliest love-bond, this earliest emotional connection of human living. We learn about loving from our first caretakers, and what wonderful students we are! For, in many instances, it seems to take half, or more, or all of a person’s lifetime to discover (if that person ever does make the discovery) that loving can be anything otherwise from what he or she learned it to be, long ago, far in the past, way back then.

In Bette’s case, the primary love-connection had never really been relinquished. She hadn’t been capable of separating from her mother and father psychologically; she couldn’t truly leave home. For, as events had so starkly and cruelly demonstrated, her move away from home had achieved only the semblance, or outer shell of independence and autonomy. She had not, psychically speaking, managed to leave home base: This left her unready, unable, unequipped for forming those new, emotionally-toned intimate ties that would serve to create a new existence, a place of her own in the world outside the family. The search for meaningful relational bonds is, of course, a crucial preoccupation of the adolescent period and early adulthood. For, however tentative, however provisional these attachments may be, they’re vitally necessary as we struggle to free ourselves from the always-somewhat-magical and primitive and deep relationship with our first caretakers.

Bette hadn’t, though, been able to first loosen, and then replace, the emotional bonds that were keeping her soldered to her parents. Unable to go about the business of making ties of her own in the world of “out there,” she had found no validity, no substance and existence in an adult world of her own that was distinct from the world of her mother and father. The underlying theme of her depression had to do with a sense of being immobilized, of being stuck. And she was stuck-in the role of being their child.

©1979 Maggie Scarf

MAGGIE SCARF is spending her Fellowship year studying depression among women.