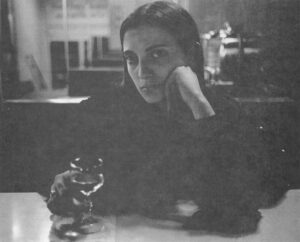

Turning the bend in the corridor, the one just opposite the nurses’ station, I saw Diana seated alone on the small imitation-leather sofa close by the elevators. The light of a winter sun, coming from the windows behind her, spilled over her dark brown hair and gave it a slightly orange tinge. She was waiting for her husband and children, as I knew-the Dahlgrens were coming in this morning for a Family Meeting. Diana’s thoughts, whatever they might have been at this moment, clearly held her preoccupied, engrossed. She, who was usually so hyperaware of others, so elaborately courteous and outgoing- sometimes almost to the point of caricature- didn’t seem aware of my presence until I was standing directly in front of her.

For some reason those few instants, the brief span of time during which I walked toward her, have remained fixed in my memory ever since; I’ve wondered why I should have retained this short reel of experience, this irrevelevant happening, so tenaciously. Maybe it had to do with finding Diana so different-so distant, so still. This was not the frantically polite and pleasing person that I knew, but someone unfamiliar, private: to comprehend her required a movement of my own understanding, a shift in my perceptions. And the scene itself-the sunlight, the sofa, the window-seemed to juggle another, older memory as well. I had the slightly eerie sense of having turned the same comer somewhere before, of having come upon this woman sitting alone, enwrapped in her own thoughts.

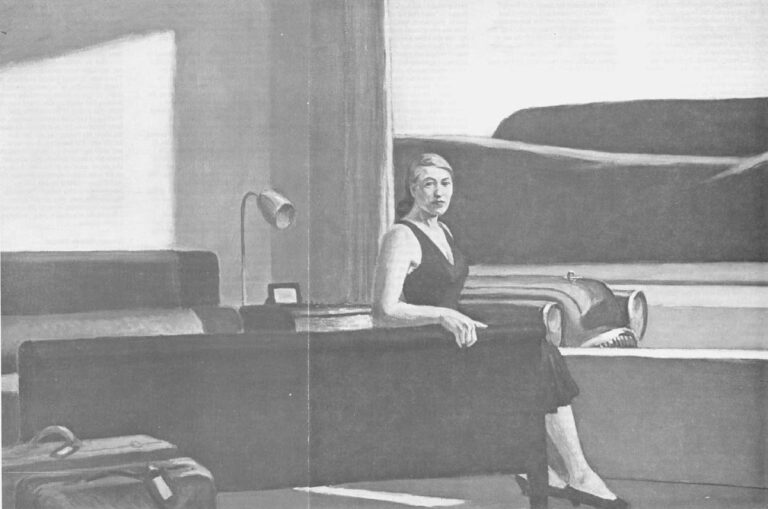

A Hopper Painting

A couple of days later- without having given much more thought to it- I suddenly realized what it was that the sight of Diana, in that pose and place, had brought to mind. And it wasn’t, as I’d thought, a memory from my own past or experience; it was of a scene captured in a Hopper painting-a picture called “Western Motel.” It is a view of a woman seated alone on a sofa near a window which looks out on a Western American landscape. The painting, which I’d seen on several occasions, had always left me feeling disquieted, uncomfortable.

For one thing, the lone figure in the scene seems to be an overnight guest at a motel; a small suitcase, and a bulging valise, are displayed at one side of the canvas. They appear to be closed and packed: but it isn’t clear whether the woman has just arrived or is on the verge of leaving. Is she staying in this blandly- furnished but comfortable room by herself-or is there someone here with her? Has that other person, if there is one, stepped out momentarily, perhaps to settle some trivial detail with the clerk at the front desk? Or has “someone” just left, departed irrevocably; is she adrift in this anonymous place with no human anchor?

Impossible to tell what the woman in the painting might be feeling. Her lips curve slightly upwards, in what might be a smile, but the eyes are bereft, flat, queerly blank. Beyond the large square of the plate-glass window are the purple and blue hazily outlined western hills: the quality of the light is ambiguous, though; it could be twilight or dawn. The more one stares at the scene the more the props of what might have been an initial understanding dissipate; the cues become more and more uncertain. Is something momentous-or nothing at all- happening? There seems no basis for hypothesizing, for making up a story about what might be taking place, about what this person is experiencing. She might be embroiled in the critical event of a lifetime, or no event at all; she could be in the middle of a routine journey, a vacation, or she could be moving from nowhere to nowhere, alone in a human universe, without human attachments…The effect is one of vague fear, even vertigo.

Even the basic identification of “age group” can’t readily be made. The woman in the Hopper work might be in her early thirties, in the first bloom of her full mature adulthood. But then she could easily be ten or fifteen years beyond that- in middle or even older middle age. She could, not impossibly, be someone in her late forties-as was Diana Pharr Dahlgren, at the time of her hospitalization at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Mental Health Center.

Forty-Eighth Birthday

Diana had been forty-eight-or, more precisely, two weeks to the day past her forty-eighth birthday-when she’d entered the hospital; her decision to kill herself had been linked, importantly so, to the passage of that birthday. She’d been feeling, for some months before that, unhinged from any meaning, any real connections, and “sense or purpose in my life’s continuation.” She’d been depressed, and severely so, but not actively suicidal until the advent of her birthday. Then, the state of misery, which she described as a kind of boring torture had intensified. Her mood, which seemed to have stabilized, albeit at a very low and painful level, had plummeted precipitously. It was beyond enduring. And what frightened her more than anything was the thought of an infinity of future such birthdays, stretching before her.

She had to stop that future. She would, ultimately, be released- through dying. If this happened sooner, it might be better. Better for her, released from this un-sharable suffering, and better for everyone else, having to contend with her pain. It had seemed, as she later put it, “to be my only sensible option.”

Patient’s Name: Diana Pharr Dahlgren. Birth Date: December 15, 1929. Marital Status: Married. Occupation: Housewife. Religion: Protestant. Race: White. Persons living with patient (Name, age, relationship)…The case was being presented, routinely, at the early-morning (8 a.m.) ward rounds, when the outgoing night staff meets with the incoming shift of nurses and doctors, psychologists, social workers, recreational and occupational therapists, etc., for an exchange of vital information. This meeting is always crowded, and there’s often a double tier of chairs around the large oak conference table: those who arrive after all of these seats are gone sit on the floor, or stand slouched against the wall. But everyone connected with the ward who can attend, does attend.

There is usually much to be communicated and shared during this woefully short space of time. There are, first of all, reports from the night medical staff on what has been happening to the patients-in terms of social interactions (with one another, with nurses and doctors, with visiting family members and friends), in terms of mood and behavior, capacity for sleep or restlessness and wakefulness-as matters have unfolded throughout the long evening hours and across the passage of the night. Then, there are discussions of those patients who are either approaching discharge, or being discharged on this particular day. Since the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Inpatient Ward is an “evaluation unit,” no patient remains longer than, roughly speaking, a three-month outside limit. And so being discharged may involve, in some instances, transfer to a longer-term psychiatric facility. More hopefully, it means the patient’s return to home, family, community, the outside world.

A Ward Briefing

Eight a.m. rounds is the time for the presentation of the new cases, the incoming patients, as well: Diana Pharr Dahlgren was, as it happened, one of four severely depressed women about whom the ward staff were being briefed during one meeting. I was making only desultory notes. Mrs. Dahlgren’s husband, Robert, age fifty, is a chemical engineer, currently teaching at– (a small, but distinguished college in Massachusetts). Patient’s husband says he knows of no recent losses, and is unable to offer any explanation for his wife’s depression. He does speak of Diana’s depressive episodes as having increased in frequency- and more recently, in intensity- over the course of the past few years. This was a first marriage, both for Diana and for Robert Dahlgren. They had been married in 1950, just after Mrs. Dahlgren’s twenty-third birthday, and their union, which both described as successful, had remained intact throughout the intervening years.

The Dahlgrens have four children, three of them still residing in the household. The oldest, a son, Mark, is a graduate of the University of California and is now a doctoral candidate at…. Mark was, in fact, a graduate student at the University of Washington in Seattle; he was far away, told little or nothing about what was happening, and never played any role in the developing family crisis.

Susanna, a senior in high school, is making college applications to school out in California, too, the Dahlgrens formerly lived in California. Susannah is 17, and is 19 months older than Wendy, now a junior in high school. The youngest sibling, Frank, is 13, and attends… ” Mrs. Dahlgren reported no serious difficulties with any of the children, although she’d mentioned that a school counselor had suggested that Frankie appeared worried and that he was having a bit of trouble making friends. Diana doesn’t, herself, perceive this as a critical problem area. She considers her children to be in generally good shape, and speaks quite proudly of them.

As the case presentation continued, my note taking became more and more, sporadic. I was allowing large chunks, great ice floes of information to slide past me, unrecorded. For, formidable as had been her attempt to destroy herself-Mrs. Dahlgren had taken an overdose of elavil, an antidepressant medicine, as well as some aspirin, found in the bathroom cabinet, and she’d been drinking at the time-this was by no means an exotic case-history. Diana Dahlgren was still, as far as I was concerned, faceless-and this sounded like the most usual, the most garden-variety type of depressive disturbance. I had already, by this time, been closely involved with a fair number of women patients whose circumstances and stories might have been interchangeable with the one now being painstakingly delineated and described.

Diana Pharr Dahlgren had, according to the Resident-in-Psychiatry who’d handled her admission to the ward, suffered increasingly depressed episodes during the course of the past few years. Patient is unable to offer any reasons, any cause, for this all-pervasive tone of sadness and dysphoria, which she describes as “feeling as if I’m in mourning for something without having any notion what that something is“… She says that only recently has this feeling become unmanageable. I put down my Bic ballpoint on the table next to my notebook, picked up a plastic cupful of lukewarm coffee sitting next to it, took a sip, continued half-listening. The doctor presenting the patient was a resident-in-psychiatry, Dr. Frederick (Skip) Burkle, Jr. It was Dr. Burkle who had admitted Mrs. Dahlgren, and it was his responsibility to share his information about her, his impressions of her and her circumstances, his initial evaluation of the entire situation with the rest of the assembled staff. He would explain the treatment regime he meant to undertake with her as well.

I looked up and down the long table at the faces of the senior ward psychiatrists, the nurses, the residents-in-training, the social workers, the two women “alcohol workers”-who dealt with alcoholic patients and their families, and who were, themselves, successful “graduates” of Alcoholics Anonymous programs-the “activities” therapists, all listening in silence. Mrs. Dahlgren experienced a severe downward shift in her mood-state, which she places as having begun just prior to her forty-eighth birthday, one week ago on December 4. She thinks her state worsened very suddenly in relation to that birthday, and then continued a downhill spiral afterwards. I was jotting along again. I paused, looked up, when Dr. Burkle looked up from his case notes: “Of course this birthday overlaps with the onset of the Christmas holidays and the beginnings of the school vacations,” he said parenthetically. “And Diana felt, she said, unable to cope with all of the things that would need to be done; she felt too spent, too drained, too anergic and miserable to carry out any of the tasks that lay before her.”

He began reading from his case notes again: Patient felt that her state of mind was insidious, was infecting the rest of the family. She decided, apparently, that they would all be better off if she were dead.

Mrs. Dahlgren had been during the exploratory “intake” interviews, unable to focus upon or articulate any issues connected to the passage of her birthday-or issues or difficulties of any kind that might have been bubbling at the source of (and provided the sudden upsurge of energy for) her impulsive move towards self-murder. There were no overt marital problems, no recent disruptions of important relationships, no special losses, no striking events, nothing that could explain in any way this state, this feeling of inconsolable grief. Nothing of any kind seemed, in short, to have happened. She had simply, on thinking about her future, decided that she hadn’t any. She was alone in the house, and drinking heavily on the night that she made her suicidal attempt. She says that she simply acted on an idea which came into her head at that moment, and that she hadn’t been working on any plan or blueprint for killing herself. The family, thought disagrees, they say she’d been making threatening remarks for a period of a few weeks or a month, prior to that particular evening…

Despite Suicide Threats…

“But where was her husband that evening-the evening when she was drinking alone?” interrupted Dr. Gary Tucker, a rangy man in his mid-forties. I paused, looked up, there was a rustle of movement throughout the room, a few murmured side-remarks. Then everyone stared at Dr. Burkle, who blushed slightly under the impact of that attention. Professor Dahlgren was, he explained, active in a wide range of college-administrative, civic and church affairs. He’d been at a board meeting of his church that evening.

“Despite the suicide threats?” asked someone wonderingly.

Pre-dating her suicidal gesture, and for a period of some months, there had been the common psychological and neuro-vegetative symptoms of depression. Mrs. Dahlgren had been feeling de-energized and joyless; she had had crying spells, felt that her existence was pointless and burdensome, that even the very food she ate had lost its taste. She’d been unable to sleep at all unless she’d slithered past the gates of slumber in a state of drunkenness. But, given that liquor could put her to sleep, the sleep she obtained was poor and unsatisfying: she erupted into alert, pained wakefulness in the small hours of the morning.

Early morning was the worst time of all. For it was at the outset of a new day (and this is common among depressed persons) that Diana felt at her most helpless and hopeless; that she felt most inferior and inadequate to the simple demands of a routine day; that she experienced herself as utterly without worth. It was almost as if the worst, the most despicable enemy she could imagine, had crawled inside her head and was directing a stream of hateful comments about her from within her. The elavil, an antidepressant drug prescribed to her by her family doctor, had swept her out of the last wave of depression. But it hadn’t helped at all in this most recent protracted attack.

The family is feeling very frightened at the moment. Dr. Burkle looked up, straightened his rimless glasses on the narrow bridge of his nose: “They do report that she’d been talking fairly morbidly, and that she had been making threats, “he commented, “but none of them had taken the talk that seriously.” Because Diana’s state of misery had seemed motiveless, unreal, her husband and children had dismissed her talk of killing herself as a ploy, a way of squeezing pity from them, of manipulatively demanding attention. They were tired of focusing on her, frustrated by her unhappiness. They’d simply not been listening-and then she really had tried to kill herself.

Contacting Diana

After ward rounds were finished, and when the staff-members were dispersing, Dr. Burkle stopped to talk with me. He had, he mentioned, told Diana Dahlgren that I was visiting this unit, and that I was interested in researching and studying depression among women. “She said she really would like to talk with you,” he told me. “She’s not just ‘willing’, but she actively wants to do so…” We agreed that I would go ahead and contact Diana Dahlgren, either by ‘phone’ or by a message at the nurses’ station; and that then I’d arrange an interview with her sometime within the next few days.

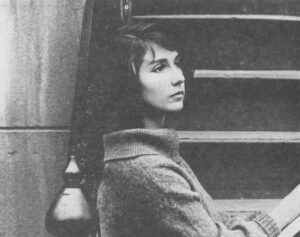

I called. But, by the time I came to see her, she was asymptomatic. There was no longer any depression to discuss. The psychological symptomatology-the crying spells, feelings of self-hatred and disgust, the loss of pleasure, anergia, helplessness, hopelessness-all seemed to have dissipated magically. She was positive and even downright cheerful in her outlook- although she kept hastening to reassure me, almost apologetically, that she “knew she had to get to work on understanding these things, these awful depressions…” The organic symptoms had vanished as well. She was sleeping and eating normally; her food “had a taste”; an annoying and perennial constipation was gone.

I had been away from the clinic the day before, a Thursday, and knew nothing of this when I knocked on her partially open door at the time of our Friday-morning appointment. I was greeted by a cordial, composed: “Come in!” She was seated at a Formica desk upon which were stacked several vases, two pretty pots of flowers, a couple of books and an unopened candy box: they were get-well gifts from friends, from neighbors, and she’d ranged them in a row in front of her to inspire her writing of Thank-you notes. On a bedside table, and not part of this grouping, stood a lone flower in a green pot-a beautiful and brilliant poinsettia.

Mrs. Dahlgren was, herself, a pleasantly groomed, ever so slightly plump woman in a black turtleneck jersey and a beige pants suit. She was attractive and trying hard to be helpful and accommodating. But she might, seated at that Formica desk, chatting so comfortably, have been a guest at a Hilton Hotel room somewhere. There was something incongruous about the woman before me and the suicidally depressed patient I’d heard described-who’d been brought to this unit in crisis. It was, somehow, preposterous, Diana Dahlgren’s being where she was. And later on in this, our first conversation, she’d voiced exactly this thought: “It’s a little hard getting used to this idea, I mean, you know, being a mental patient,” she’d observed wryly. “There’s something about it that’s somehow crazy.” Catching herself on the word “crazy,” she laughed, and I did too.

Bewildering Recovery

She considered herself, and certainly appeared, completely well. Such astonishing, almost bewildering, spontaneous recoveries are no rarity among newly admitted psychiatric inpatients. This is the so-called “flight into health,” often considered to be motivated by an up rush of desperate fear on the patient’s part- fear of confrontation with the source, or the severity and depth, of the psychological wound. To become well at once is to avoid getting to the heart of a particular matter, to seal over whatever it is that (as the person at some level apperceives and knows) is the hurtful and unknowable psychic truth.

This is the “spontaneous recovery as a means of avoiding the deeper problem” view. But of course becoming hospitalized at once accomplishes a number of things, a major one being that a person is moved from one place (usually, his or her home environment) to another (the hospital). And in many instances, Diana Dahlgren’s included, it has seemed to me as if the patient’s presenting symptoms were like a fantastically staged and elaborate psychological drama, being enacted in the service of procuring aid, help, care. Certainly, if Diana’s suicidal move had communicated anything it was that she would be helped or she would die. And so the almost absurd speed of her recovery could be seen as related to her having come to the hospital and gotten what she so deeply desired and needed…tenderness and attention.

This is the “spontaneous recovery as a means of avoiding the deeper problem” view. But of course becoming hospitalized at once accomplishes a number of things, a major one being that a person is moved from one place (usually, his or her home environment) to another (the hospital). And in many instances, Diana Dahlgren’s included, it has seemed to me as if the patient’s presenting symptoms were like a fantastically staged and elaborate psychological drama, being enacted in the service of procuring aid, help, care. Certainly, if Diana’s suicidal move had communicated anything it was that she would be helped or she would die. And so the almost absurd speed of her recovery could be seen as related to her having come to the hospital and gotten what she so deeply desired and needed…tenderness and attention.

In any event, not only those cruelly self-murderous thoughts and ideas were gone: the long fugue-like depression which had culminated in them had lifted, remitted completely. Diana, within the course of the next several days, did a steady turn-about, becoming positive and then even super-positive about herself, her marriage, her family, her future…The question was, would this new view persist?

It required no cynicism to be highly doubtful. For Diana had done nothing about integrating the sequence of events leading to her hospitalization into her current concept of herself, it was almost as if that other Diana Dahlgren had had no palpable reality, as if those intensely depressive feelings had not only been plowed over, but hadn’t quite really existed. It was difficult for the staff-because it was painful for her-to try to get her to return to that time, to focus upon the whole episode. She was splendidly better, and didn’t want to follow any fine of thinking in a direction that might upset this newfound equilibrium. She basked, for the moment, in the respite of what resembled an emotional amnesia.

Happiest Patient Contest

Diana Pharr Dahlgren could easily have, had such a contest been organized, won the title of “Happiest Patient on the Ward,” hands down. She’d begun to speak of herself as someone who’d been extremely lucky and terribly fortunate in “having gotten everything I ever really wanted out of fife.” The question of her discharge would, obviously, have to be raised momentarily; and yet most of the ward personnel remained dubious, concerned. The acute pain, anxiety, despair she’d felt- like a hole we knew was down there in her psychological upholstery- had been so quickly covered over with this bright and distracting coverlet. But how severe was the damage underneath? And how well would she hold together once she returned to her husband, her home, her family?

Diana’s contented and gratified and satisfied assessments of her life-situation sounded (to say the least) paradoxical. She had, after all, tried to commit the act of murder upon herself. Feelings of intense hate and anger- directed against her Self-had to have been there, had to have energized this act! (Think, after all, about the overwhelming, out-of-control fury most of us would have to be feeling in order to commit homicide. Suicide is homicide: the victim is the Self.) Do contented and gratified people act upon sudden impulses to kill themselves?

I don’t mean to suggest that most people don’t, at some point in their lives-some time of crisis, stress, grief, loss-think about wanting to die, or perhaps wanting to kill someone else whom they see as the cause of their pain; suicidal and murderous thoughts are not limited to mental patients. There is, nevertheless, an enormous gulf between the person who merely has such thoughts or fantasies, during a period of rage and suffering, and the person who proceeds to act upon them. This crucial divide was the one that Diana has crossed; she had done a deed, and it seemed imperative that she take responsibility for it-and for all of those thoughts and feelings and ideas that had brought her so close to dying.

But the only explanation she had for having tried to kill herself was the desire to escape- ” once and for all” – from those brutal, protracted, tortuous depressions. And she was without explanation for them. All that she knew was that the first bad attack of desolation and despair had occurred several years earlier: after that, the depressive episodes had kept coming, like waves which rose up on the placid surface of her life, rolled her over and over during a period of intense turmoil, then subsided, dissipated. She was alright, or almost alright, in between: “Just scared about when it might happen again.” The last one had been the worst; it had been the longest and most intense; it had become unendurable.

Why Me?

These depressions, were, though, nothing that Diana ever owned, nothing that were hers or proceeded from within her. I think that she experienced them as a kind of flu, an attack of disease which came upon her from outside- as if by means of a germ, a virus. The fact that she should be getting them sometimes even made her indignant: “I could understand this kind of thing happening to a whole lot of people,” she once told me, “who might be, you know, in pretty terrible kinds of circumstances. Without money to feed their families-women who are alone, without husbands to care for them-or people whose kids have gone wild or wrong. But someone like me… it makes no sense!” She shook her head, looked at me in helpless wonderment: “Why should I get into something like that-those awful, unspeakable things, those depressions?”

She waited, then, her eyes silently questioning: Had I some clues, some notions about what might be causing her pain? She herself had just spoken about women who were alone “without husbands to care for them”; and the thought in my own head was that a person can be frighteningly alone without necessarily living alone in a house. Where had her family, particularly her husband, been on the night when she’d been threatening her death- and why had he decided to go ahead to his meeting?

There were “clues” in the answers to such question; a trail, perhaps, leading to the heart of the mystery. But there were certain paths along which Diana’s thoughts were not permitted to wander. The solution, if unmasked, might be that she was truly isolated in the human world, and that nobody really cared. This answer to the riddle, as her own actions clearly had demonstrated, was one she would rather die than comprehend.

©1979 Maggie Scarf

MAGGIE SCARF is spending her Fellowship year studying depression among women.