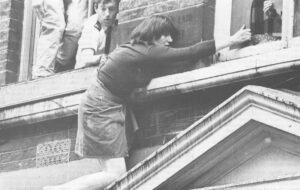

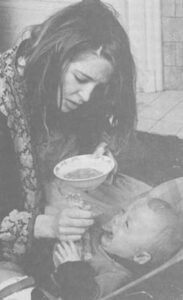

Laurie Michaelson had heard, vaguely, about a condition called postpartum depression: she wondered, a few times, if this could relate to this strange, numb, unhappy sense of herself that she was presently experiencing. But postpartum depression was, she believed, something that occurred just after the birth of a baby-and Laurie’s daughter, Katherine, was now over eight months old. It was true, nevertheless, that she’d just ceased breast-feeding the baby, and that she was feeling internal sensations that indicated that her period was coming on. There must be, certainly, massive hormonal changes involved when a woman discontinues nursing. It was the only explanation she could really give herself, for she never felt so wretched as this in her entire life.

As the Christmas and New Year’s holidays grew closer, she found herself unhappy to a degree that was truly frightening. There was no rational explanation that might make comprehensible to her this sense of inner devastation. And yet it went on, and grew worse: she had begun accusing herself of every kind of weakness and failing.

As the Christmas and New Year’s holidays grew closer, she found herself unhappy to a degree that was truly frightening. There was no rational explanation that might make comprehensible to her this sense of inner devastation. And yet it went on, and grew worse: she had begun accusing herself of every kind of weakness and failing.

At the same time, there were a dizzying array of realistic demands to be met. They impinged upon her from her every side; and she had to go on performing as mother, as wife, as teacher (for she taught social work, on a part-time basis, twice each week). She was struggling to keep up with everything being asked of her, to manage these roles well despite the mood of sadness and the certainty of her own worthlessness and inevitable failure. But she was beginning to worry, with the passing of the days and weeks, not only about performing adequately; she was doubting her ability to carry on at all, much longer-to continue this impersonation of an individual who was going about her life, and was functioning.

As far as doing anything about the ways she was feeling, Laurie assumed that — being realistic — this was a matter beyond repair. Her feelings had to do with the massive imponderables of human existence.

I interviewed Laurie in a borrowed office at the Mood Clinic, a treatment facility associated with the University of Pennsylvania, where she had eventually come for treatment when the symptoms of her depression had been beyond bearing. She’d felt too inadequate and too stupid to go on caring for her children: “I was confused all of the time, and afraid I was going to make some mistake to do something disastrous.” She had also become phobic about going outside, for she was experiencing powerful impulses to end this mounting anxiety, panic and suffering. Laurie had even confided, to a horrified friend, that she was feeling strong urges to throw herself in the path of an oncoming subway car or a bus.

By the time of our interviews, Mrs. Laurie Michaelson was well recovered from what she now considers to have been a “postpartum depression”. Her own belief, she said, was that the explanation for the terrible state that she went into eight months after her baby was born had to do with changes that were physiological, and happening within her body. The “causes” of her depression were, in short, related to childbirth and to breastfeeding: They were hormonal.

As far as the term “postpartum” is concerned, there is a statute of limitations in current medical use and Laurie Was definitely beyond it. By definition, the term postpartum refers to one of three possible general time frames: the first 10 days after delivery or the 3-month period after delivery or the wider drawn 6-month boundary. In Laurie’s instance, as we know, a full eight months had elapsed since she’d given birth. She was, therefore, a couple of months beyond the 6-month outermost limit. Her depression was not “postpartum”: at least, not by definition. Or was it?

Although current scientific knowledge of what occurs during each phase of delivery is incomplete (it isn’t known, for example, what hormonal factors come into play to trigger the onset of labor contractions) what is clear is that there are literally massive shifts in hormones, and in fluid balance, that take place within the first ten days postpartum. And it is during this same brief time-span that some two-thirds (64%) of psychiatric reactions, such as depression, emerge.

But an enhanced vulnerability to some kind of mental illness extends well beyond the ten days post delivery. For, as many statistical studies have shown, the new mother is at a greatly increased risk to develop some form of psychological disturbance for the first three months post childbirth. She is four or five times more likely to generate “symptoms” than is the woman who hasn’t had a baby within the past three months. Furthermore, for the entire first half year postpartum, the new mother is far more liable to become psychiatrically ill than are’ women in general. Taking a cold, objective, actuarial view of two populations — i.e., “new mothers” and “women, as a whole” — it is clear the former group are mysteriously more fragile.

It may be that it is the fatigue and the stress of the early-mothering process that, in itself, brings about these inflated rates of mental distress in parturient women. Or it may be that the predominant factors at play relate to the remarkable amplitude of those hormonal changes. Medical and psychiatric opinions on this subject vary. But the ancient Greek physicians, who certainly recognized postpartum phenomena, viewed the new mother’s occasionally paradoxical reactions (paradoxical in the sense that she becomes overwhelmed by misery, grief and remorse in the wake of a “happy event”) as an essentially biological occurrence.

The physician Hippocrates, theorizing about these matters in the Fourth Century B.C., suggested that the bloody vaginal discharge which continues for some four weeks after a woman has given birth, was somehow being improperly drained, and was being transported to the woman’s brain. Her emerging distress — which could take the form of confusion, delirium, delusions of guilt — was linked not only to this internal plumbing-problem, but to the hormonal changes presumed to accompany the onset of lactation.

Upon this latter subject, Hippocrates wrote that: “When blood collects at the breasts of a woman, it indicates madness.” The modern reader isn’t quite certain what was meant by this curious observation! Yet, quaint as it sounds, it does contain a never-discarded notion: that drastic physiological changes occurring within the new mother’s body-and connected both to the recent delivery and to the commencement of the nursing process-create a climate particularly ripe for the emergence of depression, madness, despair.

Over the centuries, there has been a persistent notion that the psychological problems that can flare up postpartum are mysteriously linked to the onset of lactation. In the mid-19th century, for example, “milk fever” was the name given to the mild postnatal depressions, which had begun to receive medical notice. And the present-day “postpartum blues” are often called “third day” or “fourth day blues”. The third or the fourth day after delivery is when the milk flows into the new mother’s breasts.

Both medical observation and ordinary folk wisdom appear to be in agreement on one general conclusion: the week to ten days just after childbirth is a time of unusual fragility and heightened emotionality for many, or most women. A number of research studies, carried out in the United States and in Britain, have in fact indicated that the new mother is not, so to speak, “herself’.

That is, she is in an emotional state that is unusual for her; her moods tend to swing up and down more easily, and she is uncommonly (for her) prone to weeping. In one such study, carried out at Stanford Medical School, a group of normal women — in this instance, defined as women who never did develop any acute postpartum symptoms — were studied intensively during three different ten-day spans in their lives. One was a ten-day period late in the pregnancy; one was ten days after the woman gave birth; and one was eight months after her child was born.

What emerged very clearly was that the second period (the ten days just after delivery) studied found the women in a state of heightened sensitivity and moodiness. The same person, during this ten-day span, was over three times more likely to burst into tears, than she was during the other ten-day time frames. And frequently, the woman herself was hard put to supply the reasons.

Some women reported crying because they’d read about somebody’s terrible misfortunes in the newspapers! They seemed, indeed, extraordinarily prone to identify with others, and unusually empathetic. (Were hormonal shifts of some mysterious kind supporting the emergence of this kind of psychological predisposition? To feel for another is more crucial to the establishment of a good mothering relationship than almost any other quality.)

Others among the new mothers, asked to supply “explanations” for their moodiness, emotiveness, unusual proneness to weeping, reported fears and worries about their competency to care for their new babies. Still others blamed their high emotionality on their husbands’ (or lovers’) behavior. In truth, the mate’s behavior — more than any other single factor in the woman’s environment — seemed capable of causing the mother’s unstable mood to plummet and crash.

In brief, when compared to her ordinary self (i.e., the person she was during the other two ten-day segments) the woman was clearly in a highly susceptible state. She was far more easily and deeply disturbed by any perceived slight, or hint of rejection. And threats of this sort, most especially from the father of the child, could bring forth the most intense and exaggerated response.

Scientists are still far from a full understanding of the hormonal changes associated with pregnancy, childbirth and the onset of lactation. But what is known is that, as a woman’s pregnancy advances over time, her brain is being exposed to ever-increasing levels of powerful hormones. Close to term, and just as labor is to begin, some of the important estrogens (i.e., estrone and estradiol) are found in the mother-to-be’s blood plasma at levels some 100 times higher than those seen during the latter phase of an ordinary monthly cycle. And another of the major estrogens, estriol, appears in the pregnant woman’s urine at levels that are about 1000 times higher than those seen in the course of a typical menstrual fluctuation!

During the last three months of the pregnancy, moreover, levels of the hormone progesterone (the word means “in support of gestation”) have risen some ten-fold above what they are during the latter, or luteal, phase of the menstrual cycle. The mother-to-be is synthesizing progesterone at the rate of some 200 to 300 milligrams per day: this must be compared with the high of about 30 milligrams per day being secreted during the latter (high progesterone) time of the month. The hormone progesterone has recently been singled out for a good deal of scientific interest. A vast array of research, carried out on infrahuman mammals, now suggests that progesterone exerts some “protective” effect upon the pregnant female. It appears to buffer the mother-to-be against the experiencing of stress.

According to Dr. Seymour Levine of Stanford Medical School, this particular hormone seems to have the properties of a natural analgesia. Levine, one of this nation’s leading experts on hormones and behavior, observed that there is good reason to believe that progesterone acts as an internally-produced sedative. When levels of progesterone are high, in relation to levels of estrogens circulating in the blood, there appears to be some calming influence upon the individual’s behavior.

A pregnant rat, for instance, when exposed to a noxious stimulus in the environment-such as being moved suddenly, or being given a whiff of ether-will respond with less output of stress hormones than will a non-pregnant female. It would be highly unlikely, suggests Dr. Levine, that progesterone would be having one kind of influence upon female rats and an entirely different effect in the human. “We are talking about the operation of biological systems, in general, and among members of the same species,” he remarked. “That species is Mammalia; and it’s characterized by the important feature, common to all of them, that the mother breast-feeds the young. It would be anti-biological thinking to suppose that the hormone would be operating in completely different ways when it came to differing sub-groups.”

Progesterone brings about some measure of behavioral quietude in the pregnant rat female. During pregnancy in humans, progesterone levels are about double the levels of estrogens circulating in blood plasma. One might speculate, said Levine that “high progesterone” correlates with “lowered emotional reactiveness”, not only in pregnant rats but in gestating women.

Curiously enough, too, as human female reproductive hormones are produced in ever increasing quantities — which does happen, steadily, throughout the latter months of pregnancy — so are reported feelings of enhanced well-being. This sense of generally “feeling good” is almost the mirror image of the vulnerable, highly sensitive weepiness that are seen so commonly, postpartum. In terms of statistics, there is a decreased risk of developing a mental illness, which appears to prevail among women who are pregnant. It is intriguing to remark upon the fact that immediately following delivery; there is an abrupt and precipitous decline in the levels of many potent steroid substances (not only progesterone and the estrogens, but thyroid and adrenocortical hormones, etc.) that have been circulating in the new mother’s plasma. What may be being experienced by the woman, at that point, is a biologically induced state akin to drug withdrawal.

But in any event, what is clear is that while women are more likely to develop psychological symptoms after childbirth, they are less likely to do so during the course of a pregnancy. To what degree, one wonders, is that shifting risk-rate due to internal factors — how does it connect to the woman’s profoundly altering physiology’?

Laurie had, it will be recalled, just stopped nursing her eight-month old daughter when she felt her mood-state commencing its downward slide. She had also begun to experience inner sensations, which she’d recognized, and which indicated to her that her first post-nursing period (she hadn’t menstruated during the eight months of breast-feeding) was about to arrive. The two events had been, very clearly, correlated in her own mind: she had attributed her depressive mood to mysterious and unfathomable hormonal changes. And Laurie believed, a couple of years after the fact, that what she’d been suffering from was a “postpartum depression.”

According to current medical definition, obviously, she had not done so. She was well beyond the 10 days, or 3 months, or 6-months post childbirth that could have allowed her to be included within such a category. But the fact that she had just ceased breast-feeding her baby does raise the questions of whether a radically shifting endocrine status had been, indeed, a contributing factor. Or had weaning her child, and becoming depressed, merely been coincident in time?

This is a question that cannot be answered, by any expert in the area, with a positive Yes or a No. According to recent research carried out with lactating rat mothers, it appears that one of the major hormones associated with nursing — which is called prolactin, meaning “in support of lactation” — has the same sedating, analgesic effects as does the “pregnancy hormone,” progesterone. Both of these biologically active chemical compounds seem to support a state of behavioral quietude in the mother: Progesterone and prolactin supply the female with some internally — produced “protection” against the experiencing of stress.

The nursing female is thus (like the pregnant female) a notch or two down on the scale of emotional reactivity and less easily disturbed by stressful happenings in the environment. A noxious event will, it had been shown, elicit less response — in terms of measured stress hormone output — from a pregnant or lactating female rat mother than it will from a female rat of the same age, who is neither carrying pups or nursing them.

There is one important exception to this general rule: The stressor, or noxious event, will elicit less response from the mother only so long as the noxious stimulus has nothing to do with her offspring. Some experts, marveling at the selective effects of both progesterone and prolactin, believe that these powerful hormones may be acting as “filters” that screen out what is irrelevant to the pregnant or breast-feeding female. In other words, these steroids may be influencing the mother-to-be or the new mother towards a most quiescent state of being — as long as protection of the young is not involved. And if one toyed with such a suggestion in human terms, then, as Dr. Levine remarked, “one might imagine the hormone affecting not only the pregnant or lactating woman’s behavior, but her ‘thinking’ as well.”

It must be remembered, of course, that the research being described had been carried out on infrahuman mammals. It’s not, however, unreasonable to analogize from species to species; this is surely the way we test out our drugs! In the particular instance of Laurie Michaelson, moreover, I don’t think it inappropriate to suggest the possibility that a vital factor could well have been that she’d just ceased breast-feeding her baby: a buffering and “protective” process, supported by the hormone prolactin, was at that point in time actually being withdrawn. If prolactin does serve to screen the new mother from “other stresses” (i.e., the stresses in the environment that don’t relate to the care of the infant) then the loss of prolactin meant a newfound vulnerability to those other disturbances.

Another point to be mentioned is that while prolactin and another hormone associated with nursing (oxytocin) were rapidly declining, Laurie experienced sensations that told her that she was about to menstruate. She was moving, then, into the high-estrogen, “egg-ripening” phase of her returning monthly cycle. And there is now a very well-supported scientific literature indicating that the estrogens support states of heightened emotional reactivity. The estrogens are part of nature’s design for enhancing sexual receptivity, fertilization and eventually a new birth. In the early (follicular) phase of the menstrual cycle, before their effects are somewhat diminished by rising levels of progesterone, they are dominant on the physiological scene. And they render the female more susceptible to stress.

Because she was weaning her baby, Laurie was, too, moving away from that special state of being that the British analyst D. W. Winnicott called “primary maternal preoccupation.” The connections to her child, both psychological and biological (breast-feeding), were in the process of loosening. The focus of her attention had altered. Now Laurie had to experience, as real and as painful, certain difficulties in other parts of her life that had really been there all along — but, which had been kept outside the circle of her concern. But she was experiencing them and responding to them with a difference — and she was overwhelmed.

©1978 Maggie Scarf

Maggie Scarf is spending her APF Fellowship writing about ” Depression Among Women”