South Hero, Vermont — Here, on this sliver of an island wedged like a wiener between the buns of Vermont and New York, we again attached Lady K’s three-pronged umbilical cord and settled in for a few nights.

Our campground was only a short distance to the shore of Lake Champlain, where we spent an afternoon snagging hand-sized bream for dinner. At its widest point, we were told, the lake covers 12 miles.

It was relaxing to sit on a flat rock and stare out across the expanse of heaving gray water. Kathy said it was the first time since the journey began that we had stopped asking questions long enough to just sit and do nothing. She was right. We had covered 4,50O miles and 17 states in only two months.

I also realized how physically tired we were growing. Brandon, ordinarily rambunctious as a kitten with a marble, sat watching his red and white floater through drooping eyelids. It was time to slow our pace, to adjust priorities and realign the schedule to accommodate 12 months on the road.

South Hero is a small community joined to the outside world by U.S. Highway 20, the only major road on the island. That thoroughfare is surrounded along its length by a mixture of farmlands and forests.

Burlington, Vermont, where we spent one day, was a half-hour drive from the island. It is a small and attractive college town that a sales clerk named Mary told me is the largest in that state of half a million people. Strolling downtown sidewalks, we talked with several passers-by.

Ralph Ordner, a red-haired construction worker told me how almost every resident of Vermont takes great pride in their most famous industry, maple sugar. I believed Ralph since everywhere we looked were signs advertising “real Vermont maple syrup and candy.”

Marilyn Garner said she enjoyed living in a state with a relatively small population. “The Governor and all the other local politicians know my husband and I by our first names. Where else can you find that?” She also said she believes Vermont officials are less prone to corruption because residents keep a close eye on governmental affairs. “The fewer there are to govern,” she reasoned, “the more honest you’d better be.”

The Lake Champlain area was peaceful and it was with some regret that we left South Hero after three days. At the northern tip of the island we encountered what must have been our one thousandth tollbooth of the trip and we knew, without saying, we were back in New York once again.

As usual, the toll attendant never smiled, grinned, chuckled or even snickered when I handed over the dollar bill. I did think for a moment that he had attempted a smirk, but Kathy assured me it was only the early stages of a scowl.

As with other poorly-founded conceptions of various regions, the landscape of northern New York surprised us with its farms, woodlands and largely unspoiled beauty. While their brothers and sisters in the easternmost urban sprawl were reporting that the garbage they had thrown into the ocean was coming back to engulf them, those New York residents were living at a much slower, cleaner pace. Somehow, we had always imagined New York as being a state of wall-to-wall humanity, bulging and bloated from border to border.

Niagara Falls, N.Y. — Strangers to the city, we were anxious to gulp down a quick dinner and hurry to the falls…as though they were slated to dry up the next morning. The young girl at the KOA campground said to be sure to go to the Canadian side for the best view…besides it was free.

Waterfalls rank second only to gas station rest rooms on Brandon’s list of favorite things. Once there, he stood for minutes at a time just staring at the brightly-lighted thundering wonder, then walked to a different vantage point and lapsed into another trance. He did look up to ask if fish lived in the swirling water below the falls and if boats ever went there. We said yes to both questions and he grinned.

Clouds of heavy mist rolled from the falls and rode the breezes high into the air. Tiny water particles pelted our faces and hands, but we didn’t mind. It made the fantasy of that colorful, crashing, frothy vision seem all the more real.

Inside one of the many tourist snares beside the falls, an area that reminded me of a wart growing on the face of a beautiful lady, we stopped to buy Brandon a piece of fudge. A silver-haired woman with a persimmon mouth and a sour expression stood behind the counter.

Chunks the size of my wallet were marked 65 cents, but I knew Brandon, whose body looks not unlike that of a fledgling sparrow, couldn’t hold half that much. Instead, I asked for one piece just large enough to numb a five-year-old’s sweet tooth.

Amputating a quarter-pound leg from the chocolate mass, she forced a smile and shoved it toward me. “Will this do?” she asked.

I said it looked great but seemed to be a bit much. My eyes had looked on a small sliver in one corner of the tray, “How about that piece?” I was almost embarrassed to ask. Her eyes became like slits and I detected a slight quiver in her pucker.

“Very well,” she said reaching for the slice about the size of my middle finger. I offered a palm full of coins, but she refused. “No, no…just take it…That’s a sample piece.” I tried two more times to pay for the candy, but she wouldn’t hear of it. Kathy added humiliation to my embarrassment by telling me I should change my name to Mike Cheapo.

Oh well, Brandon gobbled up the fudge and smiled his satisfied smile. I decided to mail that woman the coins just so I could retain my Christian name around the Lady K.

DETROIT, Michigan — Waiting our turn at the New York-Canadian border, Kathy and I pored over maps and atlases trying to determine the best route across Ontario to Detroit, a five-hour trip.

In desperation, I finally went to the CB radio for help. It was then, like a voice of salvation from the electronic wilderness, he responded by telling me to park the Lady K on the other side of Customs and wait for him…”Mickey Mouse” the free-wheeling, high-balling, semi-truck driver was coming to the rescue.

In a few minutes we were following instructions, waiting on the shoulder for the arrival of Mickey Mouse and his white diesel rig. Suddenly, Brandon squealed and we looked over our shoulders to see the massive truck approaching. He called for me again and I answered to discover that Mickey Mouse was actually a trucker named John Mordus.

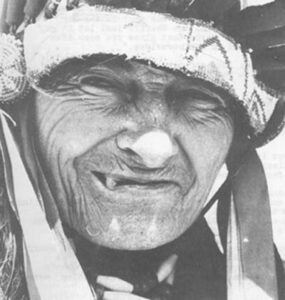

He said he was 25 years old and lived in East Detroit, but preferred to call it “murder city” because of the hundreds of people killed there every year. While more than 100 miles of concrete passed beneath, John and I came to know each other even better over channel 17 of our radios. He also said he’d been driving for more than six years and had divorced not long ago after a year of trying to make a marriage go. Most of the time he hauled loads of pork from Detroit to New York and back again along a route that meant driving as much as 3,000 miles a week.

His persistent touting of a favorite roadside cafe convinced us to eat there with him. Easing the coach to a stop behind the truck, we stepped out to shake hands with a dark-haired fellow of medium build. He recommended the corned beef sandwich for lunch, adding he always stopped at the place which was owned by a Czechoslovakian couple.

After crawling into a booth John who said his nickname was Rigor, explained how he had been born in Michigan, “but came to Detroit as a younger man to seek work.” His father owned a sand and gravel business in northern Michigan where John learned to drive a truck when he was 12.

He paused long enough to tease a young waitress about not serving his “regular” before he asked for it. She giggled and hurried off to draw a glass of ice water. “Gets mighty hot up there in that cab,” he said, running a fistful of fingers through his thick hair.

Brandon excused himself and went for the men’s room key to begin another adventure in the continuing saga of push-button hand driers and flushing commodes.

During our 30-minute lunch break, we came to know John “Rigor” Mordus quite well. He told how he had married and gone to work for his father, but the marriage failed in about a year. “By gosh,” he said, “I lost $6,000 in that deal. You can bet I’m not ready to do it all over again.”

He asked the waitress for a daily paper and hurriedly flipped through the pages until his dark eyes fastened on the stock market listings. The edges of his mouth curved upward, “Aha, up nearly a point. Not bad at all. This is how I get my kicks now…keeping up with what I’ve invested. I’m not always going to be driving a truck.”

We left the artificial cool of the cafe and stepped headlong into a broiling summer’s furnace. John kicked the tires of his truck while making a full circle around it. Not to be proven an amateur, I made a few half-hearted toe jabs at the wheals of the Lady K. Kathy laughed at me.

Brandon, who had become enamored with Mickey Mouse, asked shyly if he might sit in the cab for a minute. John grinned and heaved him into the driver’s seat. “Say, why not let him ride along with me for the next 200 miles, until we get to Windsor? Held probably enjoy the trip in an 18-wheeler.”

Kathy and I exchanged glances then looked at Brandon. He was shaking his head yes, mustering the most maligned expression possible on such short notice. We agreed to let him ride.

Falling in behind the truck, our miniature convoy rolled on past miles of green crops and ranchlands in Ontario. Again using the CB, we further cemented our newfound friendship.

He talked for a while about a bad wreck he had survived two years earlier. It seems a car containing two elderly women passed him on the highway then unexpectedly came to a screeching halt in front of his truck.

“I had a split second to decide whether to smash headlong into their car or take to the ditch. I ended up clipping the rear of their car, leaving the highway and rolling several hundred feet through a field before the truck flipped. I’ve still got the scars. Man, I grew up 15 years in those six seconds.”

John and the two women were hospitalized and he told us of an experience there that touched him deeply.” I was laying flat on my back, still hurting a lot when this young guy came in and said he was the son of the woman who was driving the car. Well, I thought here it comes…cursing, a million dollar law suit.”

“But you know what he did? He pulled out a Bible and handed it to me, saying it belonged to his mother and she wanted me to have it. That fella said she wanted me to know how sorry she was to have caused the accident and that she hoped I’d be okay. I still carry that Bible in the cab with me today.

The stories went on as the American border grew closer. John said he was excited at the prospect of getting a spanking new diesel truck which was due in the following week. He told us about the time he ran headlong into a horse that was running toward him down the highway and he told us about Carolyn.

Carolyn was a 30-year-old mother of two who was renting the bottom level of his two-story house. “She’s great,” he said, “She does the wash, cleaning and cooking and pays $150 a month rent. It’s everything I could want right now.”

A slender red needle told me the Lady K was growing desperately thirsty. Mickey Mouse said he would stop with us at the next station. As newcomers to Canada, we were aghast to find gasoline selling for 96.9 cents a gallon, even though the Canadian gallon is a quart larger than its American counterpart.

John offered to exchange some of my U.S. money for his Canadian bills since it was about four percent more valuable than our dollar in that country. I thanked him, but declined. A $5 bill bought me just over five gallons.

As we were climbing back aboard the coach, John made a suggestion, “Say, I’ve been thinking about this and why don’t you three come home with me and spend the night. We could have dinner and sit in the back yard later. It’s nice out there.” At first I was reluctant to further intrude on his good nature, but he persisted until I agreed.

He found a phone and called Carolyn to warn her of the impending horde. She said she was taking her son to a softball game and would leave the meat loaf, mashed potatoes and corn in the oven in case we wanted to eat before she got back.

An hour later John was taking us along a winding, side-street tour of Detroit’s slums. It was a sad and sobering look at the way thousands of Americans spend their lives. Blocks and blocks of homes were being leveled because the houses, which were built with federal HUD funds, were literally falling apart. Some couldn’t be sold for even $1, John said. It was an ugly view, but no more so than other blighted areas we had seen in many large cities.

Mickey Mouse lived in an attractive, white-frame house on Rein St. It was a surprisingly peaceful, suburban neighborhood that could have been anywhere in middle-class America.

Carolyn arrived soon after we did. She was small and pretty with auburn hair and eyes that sparkled when she talked. Her boy and girl kept Brandon occupied while we visited in the back yard. It was good to be in a home again. We had forgotten how much room a modest three-bedroom home contains.

John said he was deeply troubled by the taxes he was having to dole out each pay period. Vanishing into the houses he emerged momentarily with a handful of salary stubs. “Just look at these,” he said, jabbing them toward me. “It’s not fair to penalize people like this because they don’t happen to be married.”

The stubs showed John averaged earning between $400 and $500 weekly, but only took home about $260 after taxes. It did seem to be an extraordinary amount. “I knock my brains out on that road all week and end up giving half of it to the government. What kind of way is that to live?”

I asked if he was a Teamster. He nodded. “Yea, I belong but I don’t feel like I get a thing from it. I’m paying that $9 a month just to keep my job is what it amounts to.”

We were comfortable and relaxed in Mickey Mouse’s house. He and Carolyn made us feel more than welcome. We had become a part of their lives and they of ours. When bedtime rolled around John wouldn’t hear of us sleeping in the Lady K. Nothing would do but for us to take his bed. Brandon slept with the kids.

Rising early the next morning, we made preparations to strike out toward Middlebury, Indiana, four hours southward. Carolyn brewed coffee while John talked about the thousand-mile run he’d begin that afternoon, a trip that would last well into the next day. There was no dread in his voice. He had grown accustomed to the marathon jaunts. I secretly wondered what it would be like to spend a career behind the wheel of a smoking, roaring mechanical beast. Our 5,000 miles had caused my eyes to blur on more than one occasion.

Before final goodbyes, we promised to write John and Carolyn. They said they’d do likewise. They were standing side by side waving as we pulled away from the house and made our way down Rein St. in East Detroit.

MIDDLEBURY, Indiana — Four hours of driving across the lower third or Michigan brought us to this small village that hugs the northern border of the Hoosier state.

This was the birthplace of the Lady K and we had come full circle since pulling her, in 25-mile infancy, from the Coachmen Industries lot in mid-April. There were a few minor repairs and adjustments and while waiting, we took a closer look at Middlebury.

It was a rustic place where the sight of horse and buggies is commonplace. A sign standing in front of one gas station asked us to wave if we couldn’t stop in and the principal food store is Harding’s Friendly Market.

Amish men, women and children dressed in black were walking the sidewalks. Brandon was fascinated by their bonnets and long, silver beards. In the afternoon we picnicked on hamburgers beside the trout-laden Little Elkhart River that flows through the center of Middlebury.

Between bites, we counted 12 carriages pass by en route to and from the town. Several motorists roared up behind the clopping buggies and raced their car engines. When the chance came to pass they flew by, leaving the carriages in a gray haze of exhaust. The Amish would just smile and wave at the strangers.

The more we met and talked with the Amish, the more I became taken with their fundamental lifestyles and beliefs. They are a people who’ve accepted being passed by a mechanized, self-seeking society while living in the same way our ancestors did more than a century ago. Amish men and women were some of the friendliest people we had met on our trip.

They basically believe in hard work, staunch faith, helping each other and an unadorned life, even to the point of refusing to be photographed.

Curious about the performance of Amish children in public school, I sought out a third grade teacher named Cathy Morgan, who lived in Middlebury. She told me she’s never had a discipline problem with an Amish child.

“The parents are very cooperative with any learning problem that arises,” she said, “Many leave public school when they’re 16 to work on the farms. Some do go to the vocational-technical school near Middlebury.”

The 28-year-old instructor said she holds a great deal of respect for the Amish. “There’s a spirit of cooperation between them that’s hard to find anywhere else,” she said. “I remember during the Palm Sunday tornadoes several years ago there were many Amish who lost homes and barns. In a few days, there was a large group of Pennsylvania Dutch in this area to help their people rebuild.”

I asked if she believed the Amish simply choose to ignore the rest of us. “Oh, they are aware of the world outside, they’re certainly not ignorant, but neither are they going to campaign for any candidate. They just don’t take part.”

There are about 1300 people living in Middlebury. The town has a main street lined with tall shade tress. People acknowledge you as you walk the street, especially the Amish, who seemed always to be smiling. The streets that feed the main thoroughfare are quiet. Several residents are identified by wood-burned plaques attached to mail boxes.

We watched one man pilot his riding lawn mower down the center of town, past a tiny store with a sign that boasted “Best Ice Cream Anywhere.”

One of those wood-burned signs downtown read Middlebury Independent, a weekly newspaper located a block from the main street. There, I met another Mike who had recently come to Middlebury as the new editor of the Independent. He was native to Indiana and eager to talk about the town and the Amish.

“The Amish are people who know how to work,” he said. “They also know how to eat three good meals a day and how to get a good night’s sleep. In short, they know how to live. Oh, I realize they’re unusual and there’s been a lot written about ‘clippity-clop, look at the funny Amish,’ but the truth is they are self-sufficient and that’s how they want it to be.”

Mike also told us he inherited editorial control of a “folksy paper” and he plans on turning into a newspaper of “statement journalism…facts and objectivity rather than opinion and gossip…”

We spent half an hour talking and could have gone for an hour, but Brandon was growing impatient and I knew Kathy was probably tired of making circles inside the town’s gift shop/

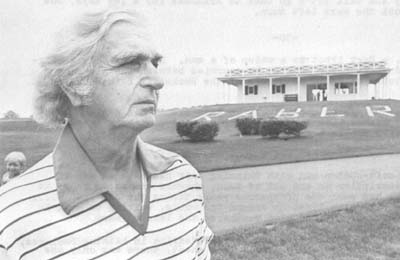

Bristol, Indiana — Word had it that in this town lived John Raber, a former Mennonite who claimed to be responsible for the presidency of Gerald Ford.

Several had mentioned the man as being an example of what is possible in America for a person with courage, drive and tenacity…he was self-made.

We drove the Lady K from Middlebury, Indiana, to a golf course owned by Raber and were invited to spend the night beside the maintenance shed. That afternoon, I met the white-haired man who was 70 years old. We sat together over a cup of steaming coffee to untangle the local legend from actual fact.

His story began as a farm boy in Michigan. “Farming was all I knew,” he said. “I always hoped to one day get my father’s small place, but he sold it when I was a teenager. That didn’t discourage me, though. I went to Elkhart and married the daughter of a wash woman and we rented a farm for quite some time.” John and Myrtle now live only a few miles from the course.

He said he lucked into buying his first farm during the Depression for $600 in cash, a $400 loan from the bank and a promise from the owner that John would have to only pay interest on the balance for several years.

“From that I built everything I’ve managed to accumulate during my lifetime,” he said. Those holdings are considerable and today include a 27-hole golf course and a new type of golf layout he’s patented called Four-Square. “You can play Four-Square with only 10 acres and two greens,” he continued. “I built this course and one other in Texas and, by golly, I believe it’s going to be the newest thing in golf. You can build a course for around $20,000 and have one for apartment houses or condominiums.”

I was most curious about the claim that John was responsible for the appointment of Gerald Ford as President. He sailed and stared at the ceiling for a moment, Well, you see, I once ran for congress against Charley Halleck of Indiana and came darned close to defeating him. That was in 1964 and Halleck was then House Minority leader.”

“Now up until that time, no one had ever come close to beating him and when farmer John Raber came within one and a half percent of doing it, well, it sorta shook his credibility in the House. When he went back to Congress Gerald Ford challenged him for that leadership position and won it. Ford’s position as Minority Leader was a big influence in Nixon’s naming him his successor.”

“So, you see,” he continued, “if I hadn’t done so well against Halleck, Ford would probably never have gotten that House position away from him and the future would have been changed.”

I understood his logic, but said I needed a night’s rest to digest it.

The next morning I learned more about John. He was expelled from the Mennonite Church because he bought life insurance which was taboo in that religion. “Maybe that was for the best,” he said, “I’m not a member of any formal church now. I believe God exists inside you and me and all of us. All that really matters is how we treat each other.”

As the crops on his farm grew through the years, so did his reputation as a reliable and capable person. The late John F. Kennedy came to know him well and, when Kennedy ran for President, John headed his campaign in Indiana. During the 1960’s he was one of 20 U.S. farmers who traveled to Russia and reported on agricultural conditions in that country.

“I was the only one who wrote a minority report,” he said. “I told the government that Russia’s climate would keep them from ever becoming a serious competitor in food production with the United States. By golly, you know my report turned out to be right.”

Teasing him about an ability for forecasting, I asked where he believes we, as a nation, are headed. A serious expression came over his face.

“Pretty soon there will cease to be nations,” he said. “There is no other alternative. We’re all on a space ship together. What happens in one place today will happen here tomorrow. You know what kind of weapons there are in the world now.

Running an aged palm though his wavy hair, he sighed and continued the train of thought. “You know, it takes people nowadays as long to get to the other side of the world as it did for their ancestors to get to the county seat a century ago. Just think about that.”

John is up at 5:30 every weekday morning and he flips on the television set to take a college course offered over the airwaves. Then it’s off to the course where he plays golf with several elderly friends who help him take care of the place in return for free golf and riding carts.

As if John doesn’t stay busy enough, he undertook to build a float of George Washington crossing the Delaware last Spring and has since taken it to parades throughout the state. He even had a George Washington costume made in Mexico and he rides in front of the boat. “I just wanted to do something for the Bicentennial,” he said. “I’ve gotten enjoyment out of it and I hope others have, too.”

That afternoon, we collected Brandon from a dirt mountain he’d been erecting since we arrived and told John goodbye. Wheeling the Lady K from the parking lot, I reviewed the many things I’d learned from him.

His parting words rang clearest in my mind. Since they seemed to summarize everything he had said during the hours we spent together. “It’s easy to whine about how tough things are today, but I’m here to tell you if you’ve got two strong hands and a good mind and you’re willing to make some sacrifices, you can still do anything you want to do in this country.”

John Raber was like most of us, a living, breathing story waiting to be told. It was interesting to realize that every person we’d met along the journey had a story worth telling. No matter how poor, ordinary, wealthy or outstanding. There is a common denominator of humanity and an interest generated from that condition.

The Lady K was purring like the kitten Brandon was coloring at the table. I looked at Kathy and said let’s go back to Arkansas for a few days. She grinned and we took the next left turn.

HOT SPRINGS, Ark. — Bert Abbot is a wisp of a man. Sporting only a hairline mustache and white boxer shorts, he scurried between the gleaming white porcelain tubs and polished marble of the Buckstaff Bath House on Central Avenue.

Trying to see Hot Springs as objectively as possible, I had decided to do something most residents have long taken for granted…take a thermal bath in one of the city’s public bathing houses.

Bert was appointed my attendant, and a good one he was.

For 30 years the soft-spoken man with thinning hair had ushered men of every physical description in and out of tubs, showers and steam rooms at the Buckstaff. He had seen the prosperous years during the mid-1940’s….years when people literally lined up around the walls, waiting to soak in the soothing hot waters. He had also weathered the leaner years.

Although the Buckstaff has survived an overall decline in bathing business, at the time I disrobed and wrapped myself in a sheet, there was only one other fellow in the bathing hall.

At first Bert told me to sit in a hot sitz bath, mumbling something about it being good for hemorrhoids. I didn’t have those but the funny little seat with gushing hot water felt good anyway.

Watching him move through the spotless room arranging and picking up sheets and towels, I pondered on the fact that this hot, humid area had been that man’s life for 40 hours a week during the past three decades.

After 10 minutes he motioned for me to enter a small cubicle where a tub of hot water waited. A metal thermometer rose from the and near my feet. The red needle sat squarely on 100 degrees, but it didn’t feel very hot to the touch, “It’s as hot as it should be,” he said.

A flick of his slender wrist sent the whirlpool to growling and spewing like popping the cap on a hot soda. I relaxed into the water and Bert sat beside me to talk about himself.

He came to the Buckstaff after spending four months working at the area Job Corps in 1946. “A friend told me they had an opening, so I same up here and applied. I didn’t know nothing about giving people baths, but they hired me and I learned fast.”

Bert, who is 61, said he grow up near Hot Springs, but never got past the seventh grade in school. “I enlisted in the Army during the war and fought in an artillery division in Europe. When I got back, I went to the Job Corps, then here…and I’ve been here ever since.”

He said he and his wife have raised three children in nearly 30 years of marriage. All are grown and gone.

“I’ve been thinking about retiring one of these days,” he said. “Thirty, years is a long time and I figure I’ll be able to draw my Social Security in another year. They don’t have a retirement program here, so we’ll need that income.”

I asked what he’ll do when he retires. His wants are simple. “Well, I’ve got a little garden beside the house and I enjoy working there. I’m so used to working, I don’t know what it’d be like to just quit doing it.

Twenty minutes passed quickly, but conversation has a way of dissolving time. Bert next escorted my towel-draped body to a five-foot by four-foot, glass-topped cell. “Sit in here for about two minutes,” he said.

Plopping down on the small bench, I watched him shut the door. It was a tiny, claustrophobic closet with hot water that trickled beneath your feet and a pipe that hissed steam into the humid air.

My mind began to wander, flashing to pictures I recalled of similar cells where American prisoners of war were kept for years in Vietnam. I wondered how anyone could survive in such a compartment.

I also wondered how many if any, other bathers had thought the same sort of thing when they watched the door being shut on them.

I’d taken all the heat I could bear when Bert opened the door again and led me to a vinyl couch where I lay down and he covered me with a sheet. Again, he sat beside me and talked.

He couldn’t say if the bathe helped to cure any affliction, but he knew they soothed aches and relaxed people better than anything he know of.

I was beginning to feel almost limp. It was a comfortable sensation similar to the feeling I have just before drifting off to sleep.

Bart said he bathed 7,321 men last year. But he wasn’t certain how many he had assisted in 30 years. “Must be a million,” he said with a laugh.

“You know,” he continued, “I’ve seen three bath house managers come and go since I’ve been here. The first one died not long after I started. That’s one way I can tell how long I’ve been here.”

Bert said he has a natural tolerance for the humidity and heat that generates in the bathing room each day. “It’s a little better in the winter when you can leave here and get some relief outside. In the summer, I just walk out of one steam room into another outside.”

We talked for another 20 minutes about his job and family and, before heading to the final shower, I asked what he thought about our country.

“Well, I don’t got out of this room or outside of my house all that much anymore, but it seems to me we’re in as bad a condition as we’ve ever been…not the same as the Depression, but in a different way. We don’t have the leadership or the concern we once had. I wish I was smart enough to see where it’s all leading.”

Stepping into a tepid spray that spat from every angle, I closed my eyes and tried to imagine working in that glistening marble steam room for 30 years. I couldn’t.

Her name was Tawny Godan. A native of Yonkers, New York, the attractive 19-year-old was passing through Hot Springs and stopped to talk for a few minutes.

I wondered if she had detected a mood of Americans during her travels. She said she sees a lot of people reflecting overall brighter outlooks following post-Watergate cynicism. “People are thinking maybe it’s time for a change, to re-adjust. But then who knows? Maybe after the election we’ll be right back in the cynicism again.”

She added that most of the people she talked with on her travels were middle-aged Chamber of Commerce officials and Jaycees.

I was curious if Tawny, along with the good, had seen any of what I call ugly America…the hungry children, castoff elderly, those thousands and thousands who, for one legitimate reason or another, can’t sufficiently help themselves.

She said she didn’t consider them an individual part of the country. “They are a part of America, those people…and they have given us a lot culturally. Their situations are unfortunate, but you find that in every country, it took a long time to get that way and I just don’t really believe that people have to be that way.”

“People who can do something about helping these people first have to see the need,” she said.

She spoke rapidly, almost too fast to follow. But I managed to hastily jot my notes in guesswhat scribblehand.

Before leaving, I couldn’t resist asking about her childhood. She smiled and said she was an only child. “I was raised with love and discipline. There were always adults around to ride herd on my extremely active imagination.”

“I went through all the phases of wanting to be a ballerina, a model and even a missile technician at Cape Kennedy.”

She was late for a luncheon, so we shook hands and said goodbye, but as she was walking away, Tawny told me to look her up in Los Angeles under the name of Mrs. Miles Little after December. If I was interested in finding out how an ex-Miss America feels.

HARRISON, Ark. — An odyssey across America in search of a human spirit that binds us all wouldn’t be a trip at all unless the Lady K rolled through the small mountain community where the seeker drew his first breath.

Scattered everywhere in evidence of a town sprinting headlong in a race to become a city. Colonel Sanders and that funny little Italian fellow, the one holding a pizza above his head…well, they both live here now and word has it Ronald McDonald might be settling in soon.

Winding along residential streets, the Lady K passed my birthplace, a three-story house now leveled, replaced by a parking lot and clothing store. It was only 144 fleeting months ago that my mother, father, sister and brother were beside me in a buff brick home along Vine Street. A radiator shop sits on that spot now. Several cars were waiting to be serviced.

Despite passage of 12 years and the addition of 3,500 people, there was still some left intact here. Businesses around the bustling downtown square still sport familiar faces, as does the antiquated redbrick courthouse where Rue and Elaine Masterson filed their first child’s birth certificate in 1946.

A barrage of memories fought to capture my attention. There was Roy Klepper’s Cafe next door to the Lyric Theatre where many summer hours evaporated in the back booth…and Kirby’s Drug Store with chocolate fountain cokes and those damn pin ball machines that callously gobbled up our parent’s quarters…the navy beans and corn bread at Cedric’s when we’d sneak away from school during the lunch hour. It’s called the Koffee Kup nowadays.

I doubt there are many who can return to the scene of their youth, of those teenage years, and not experience a twinge of longing for the freedom and enthusiasm of that time.

But even more meaningful than the remembrances of buildings and places, I saw Bill Hudson again.

You know…Bill…the one who defied his high school buddies by befriending the new kid in school…the only one who didn’t scoff at my white buck loafers and Wrangler jeans like the other guys were doing between class bells.

As the offspring of an Army officer, I had come and gone like a yo-yo from Harrison throughout my childhood, to return a final time during the ninth grade. It was then I came to know and respect Bill Hudson.

He’s Dr. Bill Hudson now, a practicing dentist with a modern office across from the radiator shop I mentioned earlier.

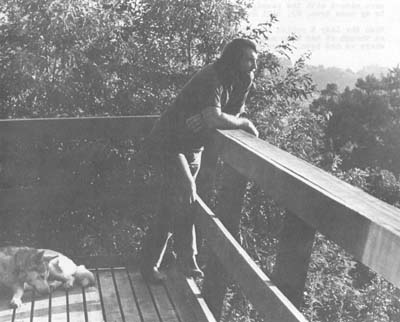

Bill insisted we spend a few days at his A-frame home on the side of nearby Gaither Mountain. A bachelor, he lives there with a personable Alaskan Malamute named Chinook. Brandon fell in love and wanted to take her with us, but she was almost as big as the Lady K. Besides Bill said he’d sort of grown attached to her.

After hamburgers on the hibachi, we sat on his redwood deck overlooking a valley and distant mountains to relive the past and discuss the present.

In 1964 we agreed the most important things in our lives were an afternoon wading Long Creek with fishing poles, cruising through Fisher’s HiBoy Drive-in restaurant (now a real estate office) or an impromptu party in someone’s carport where we could squeeze the girls tight while swaying to the rhythm of a Brian Highland or Bobby Vee in between the kissing games. There was nothing else, except maybe football practice and parking along Spear’s Lane.

Bill chuckled, recalling double dates in his black ’50 Ford and my habits of slicking hair with Brylcream, hiding pimples with gobs of Clearasil and powdering with enough white Old Spice Talc to give me a ghost-like face.

The biggest worry for Bill back then was when he threw an engine rod in that old car. We had been on an all-important crow-shooting trip and were headed back to town when it happened. Whirrrrrrrr, bang, bang, bang, bang. I could still recall that pounding beneath the hood.

Life was so simple then, but from where we stood on the mountain of living we couldn’t see it. We really didn’t know what we’d become…and were not the least bit worried about it.

An awful lot of minnows have swum beneath the Crooked Creek bridge since then. Harrison and Bill are 12 years older. He stands on a higher cliff up that mountain, surveying his existence and purpose from a different angle.

“I get fulfillment from my work,” he said, stroking his reddish beard. “That’s why I’m doing it I guess. But it bothers me to know there are some people who think professional people like dentists and doctors are interested only in making money.”

“Speaking strictly for myself, I get tremendous satisfaction if I can ease someone’s suffering, or reconstruct a mouth in hopeless shape.”

Bill went on to say how there have been several patients who skipped out owing hefty bills, but he hasn’t called in a collection agency. “Maybe I’ll have to start doing that,” he said. “Although I don’t really want to.” Neither has Bill been charging people who don’t show up for appointments. But then, that’s a part of Bill Hudson that hasn’t changed.

“I don’t know if it’s even possible to effectively communicate with patients about money,” he continued, “If I sit down and explain how $10 of a $15 charge goes for my office expenses, they think I’m on the defensive about my bills and having to make excuses for the charges.”

We talked about how difficult it seems for some people to keep from enclosing a double dose of resentment toward a doctor or dentist with payment for his or her services, and how those same people will dole out $100 or so a week for groceries without a gripe or hard feeling. “In a grocery store, who are you going to aim your anger at? The stock clerk? The checker? There really isn’t a central figure like with a dentist or doctor,” he said.

We lapsed into silence for a few moments, listening to the night sounds of insects and frogs. “I can understand how some must feel, seeing someone else like a professional person with a lot of nice things,” his voice broke the still. “I mean, I believe I can see how they have hard feelings and think it’s not fair. It’s a thing I’ve wrestled with inside for some time now…”

The conversation soon evolved into a philosophical discussion about Americans who find themselves on the point of society’s spear after setting themselves apart from the norm either socially, professionally or financially, and how they frequently become overnight targets for unfounded criticism and resentment.

“We live in a country where so much success is available to those who strive for it but, once earned, you’re often scorned by those who don’t put forth the effort,” he said.

The evening wore on until the hour grew late. In sharing newfound beliefs and ideals, I began to see that, beside me, in many ways was a different Bill Hudson.

Oh, there were the flashes of younger Bill, just as there remain those bits and pieces from the Harrison of a decade ago.

Also like the town of Harrison, he, too, had become much more complex, far more mature with the passage of the 12 years and like Harrison will always be my home town, Dr. Bill Hudson will always be my friend…I know that.

When the Lady K rolled away from Bill’s house on Gaither Mountain, I felt as though it had been meant that we spend the time there to see, together, where we had been, where we were and what, if any sense it all made.

Received in New York on August 4, 1976.

©1976 Mike Masterson

Mike Masterson is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Sentinel Record (Hot Springs, Arkansas). Mr. Masterson will travel throughout the U.S. with his family and write about the country and its people in 1976. This article may be published with credit to The Sentinel Record and to Mr. Masterson as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.