November 1970

Damascus during Ramadan and while the latest Syrian coup was cooking was subdued. Yet it evoked an air of tense expectation. The outward calm concealed an intense struggle taking place between the civilian Baathist ideologists and the army officers who put and keep the Baath in power.

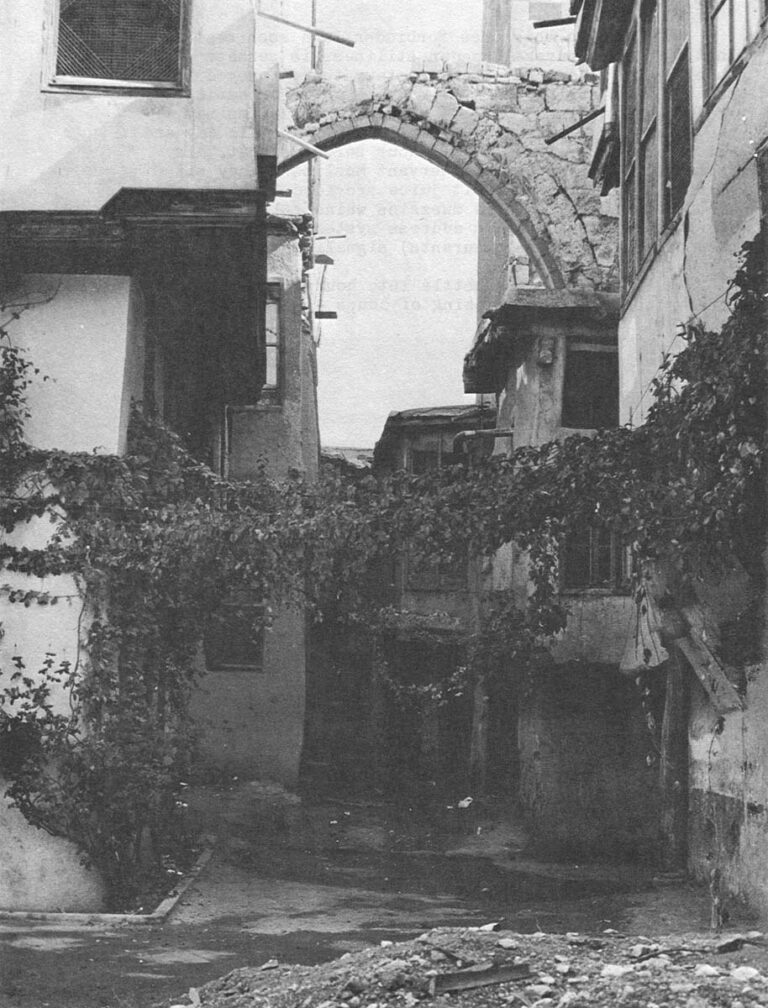

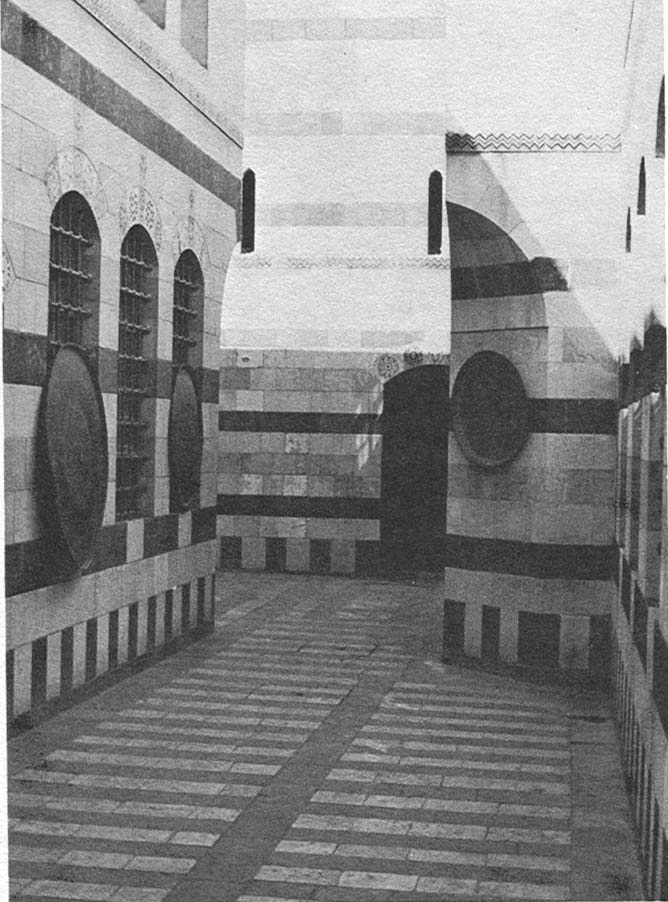

Daily affairs proceed at a pacific pace. At the Omayyad Mosque, the pious – young and old – gather for prayer. Some sit cross-legged reading Korans. A score surround a wise elder reciting. Several doze in the shadows of the arcade of arches, which form a grand chiaroscuro in the Mosque courtyard.

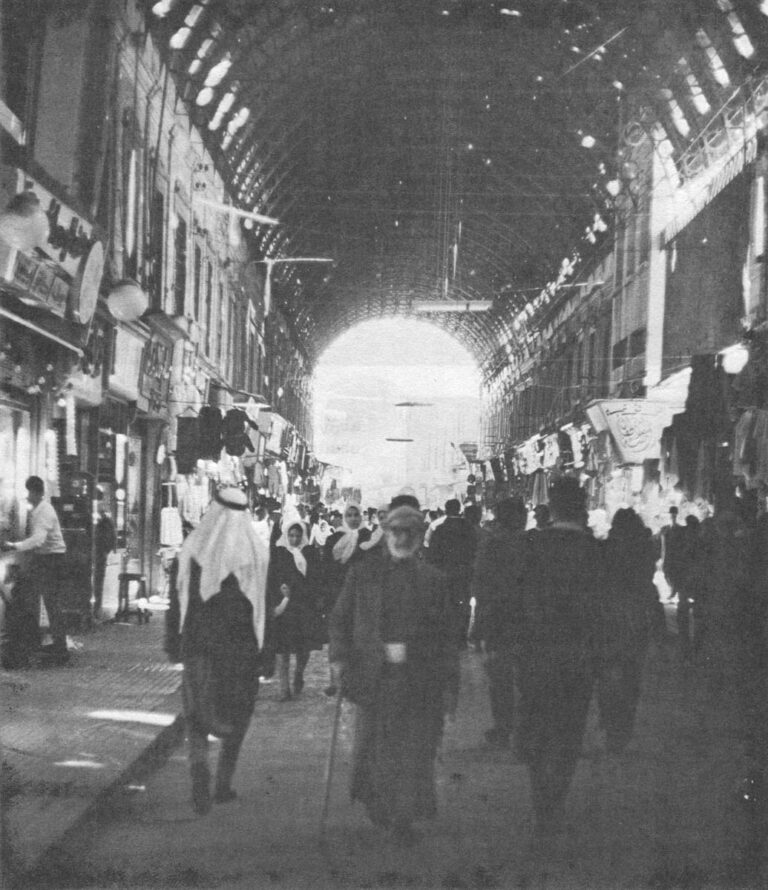

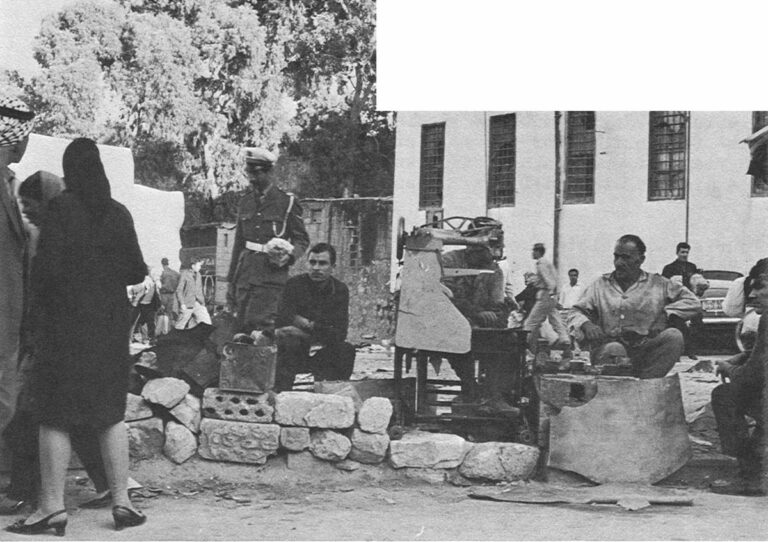

In the lanes of the souq (market) stretching out from the Mosque like long, crooked fingers, the women even those in western dress – shop veiled in solemn black and wearing dark skirts below the knee. Military uniforms are the vogue for at least half the adult male population of the city. The crisp, camouflage colors of asSaiqa, the Syrian controlled commando organization, are striking even in the semi-light of the covered lanes.

The city’s edgy tranquility may tell something about the Syrian economy as well as the burdens of fasting or coping with frequent coups. According to The Economist Intelligence Unit’s latest Quarterly Economic Review, “The steady increase in imports of capital goods for Syria’s five-year plan (1966-70) is preventing the improvement in the country’s visible trading position….” In addition, Syria spends a great deal on costly but unproductive military items. Moreover, an economic officer in the United States Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, points out that last year’s severe drought has forced Syria to import staff-of-life grains, wheat, and barley, which she had exported in the past.

This year’s rains, however, have come on schedule. And cotton, Syria’s main cash crop, is irrigated and thus not dependent on the vagaries of weather. Nevertheless, balance of payment considerations still may have figured in the significant alteration of Syria’s policy toward American visitors bearing hard currency. Americans had been generally unwelcome since the June 1967, Arab-Israeli War when Syria broke diplomatic relations with the United States. However, since the September 1969, inauguration of the Damascus International Airport, tourists and businessmen have found entry increasingly easy. A French firm is constructing a hotel near the airport. And two months ago, Pan American Airways became the twenty-first international airline landing at Damascus; Pan Am’s flying to Damascus is the price paid for the right to overfly Syria.

Many foreign visitors, however, motor to Damascus from Beirut. A weekend is sufficient time to see the city’s high spots. The drive takes approximately three hours depending on the queues at the border. Tourists in private cars or taxis rented for the day are usually not searched. But “suspicious” looking people like one elderly Arab lady who brought a suitcase full of plastic children’s slippers from Lebanon to sell at a profit in Syria, are delayed indefinitely.

En route through Lebanon, one passes the mountain villages – the favorite summer spots for Beirutis and the rich, agricultural Beqaa Valley. The bustling towns and busy countryside of Lebanon seems to give way to contrasting Syria scenery. It’s a hilly, beige, landscape with only a little green mercifully left by grazing goats. The quiet view is occasionally interrupted by billboards advertising Eastern bloc airlines or Japanese electrical goods. Work crews are spotted improving the highways.

A “camouflaged” factory with a dinosauric-proportioned floral design marks the outskirts of Damascus. So does the military base protected by anti-tank constructs, which look like clusters of crisscrossed railroad ties. But the age-old sign that you have reached Damascus is when the landscape, watered by several rivers flowing into Damascus, becomes green.

The city’s broad, tree-shaded boulevards carry little traffic. Lebanese taxis are required to take passengers directly to a spot in front of the Semiramis Hotel, which holds the dubious distinction of being Damascus’ fanciest. From there, visitors looking for a Syrian taxi – often mid-nineteen fifty American models – discover that military jeeps are easier to find.

Tourists circulate from the Omayyad Mosque to Al Azm Palace, which has been converted to a museum to the well-organized National Museum. They all light on the souq’s treasures of leather, copper, brass, gold, brocade silk, glass, and wood. The Lebanese, for example, who are world-renowned for their shrewd trading sense often give shopping lists to travelers heading for Damascus.

Visitors to this once forbidden land soon realize that Syria’s apparent Ramadan stillness is perhaps deceiving. As one Damascene restaurateur, annoyed by bad business during the Muslim holiday ban on eating or drinking during daylight, said: “The Muslims say they fast for a month. But really they fast all day and eat all night.” About a half-hour before sunset, his restaurant fills up with observant Muslims. They sit staring at glasses of fruit juice provided by the management. The sun sets. The muezzins whine “Allahu Akhbar” over the minarets’ public address systems (which is then piped into the restaurants) signaling the breakfast.

And the Damascenes settle into hours of feasting. Life – including the hatching of coups – goes on.

Received in New York on December 1, 1970.

©1970 Paula Stern

Paula Stern, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Stern and the Alicia Patterson Fund.