January 1971

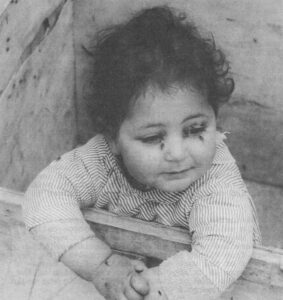

The Mukhtar’s baby sister has mother-in-law problems. In-law problems are not unknown in Ain Kfar Zabed, but the case of Tamam Sarkis has an unusual twist. The problem with Tamam is that she has been taught to think.

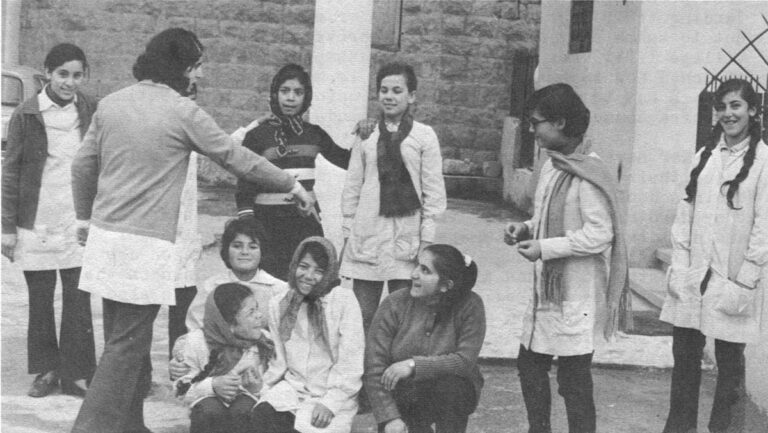

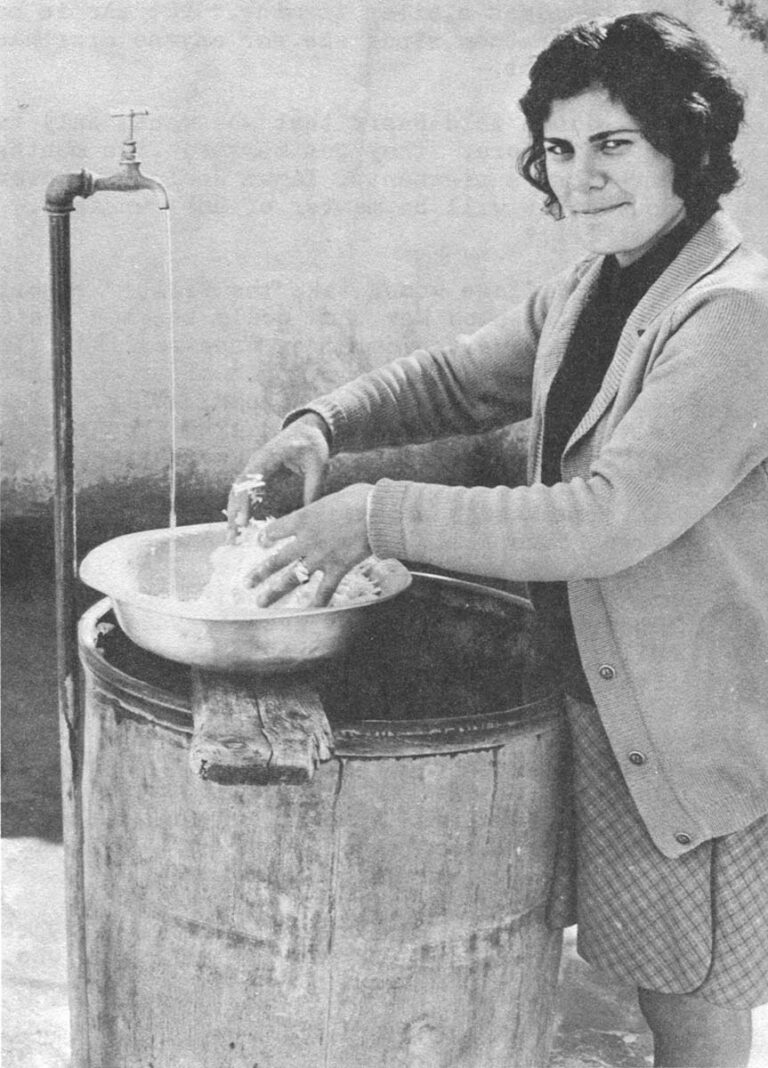

Tamam has spent six years under the tutelage of Mademoiselle Antoinette, the Directress of a vocational school for girls in the village. Tamam has learned needlework – embroidery, knitting, and crocheting and “to do needles,” which in colloquial Arabic means to administer a shot. Tamam is a nurse’s aid, the only salary-earning female in the village.

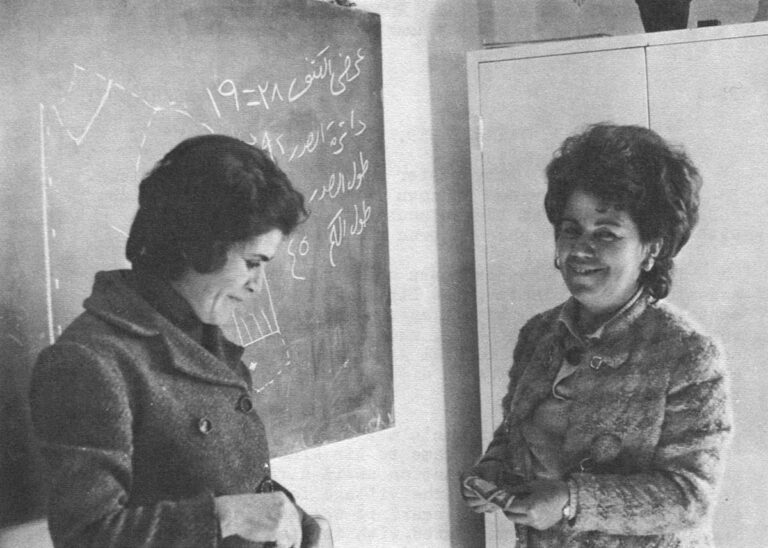

Twelve years ago, Tamam’s mentor, Antoinette Chidiac, “doing a Christian deed,” came to Ain Kfar Zabed by donkey, the only means of transportation until a road was built five years ago. She chose the village for her charitable enterprise because she had heard it was the poorest around. Six years ago, she established, with the assistance of the Lebanese Government’s Office of Social Development, a medical clinic and school serving the villages in the Eastern Beqa1a Valley neighboring Ain Kfar Zabed.

Mademoiselle Chidiac focused on the problem, which she felt most pressing: “getting the women out of the fields” and “ending their treatment as animals or slaves.” Her aim is not to teach city habits but to improve the quality of village life. Her rationale, for example, for teaching the students how to set a proper table is not to teach “good” manners but to eradicate the unhygienic practice of eating out of a communal dish with one’s hands.

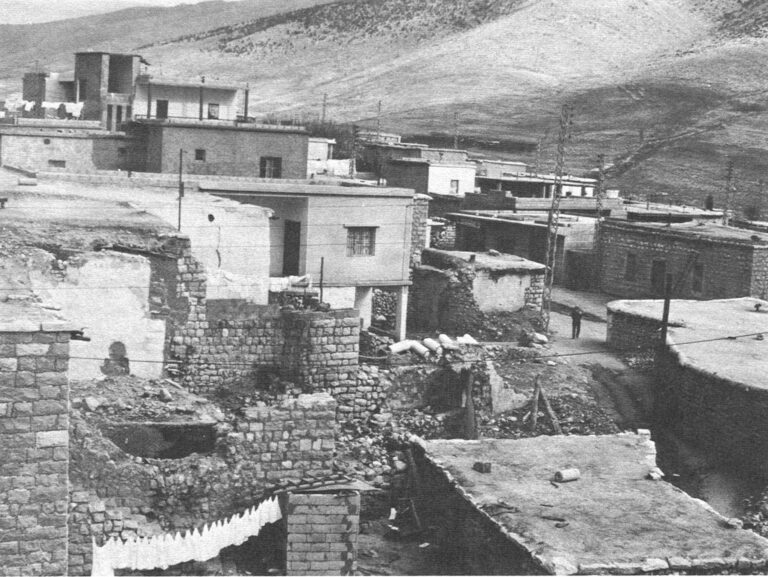

Her seventy students commuting from neighboring villages value their education and express the desire to continue their schooling. But realistically assessing their futures, they devote most of their thoughts to engagements, marriage, and children. The girls are also acquiring the values of modernization. Although they come from villages, which are barely better off than Ain Kfar Zabed, they look down on the community whose crooked, muddy, maze-like paths serve also as sewers for rubbish and drainage ditches for the frequent rain. The fact that Tamam was the first and still one of the few girls actually from Ain Kfar Zabed who has managed to overcome the village’s conservative distrust of the school and dares attend classes does not escape the students attention.

Even without her modest education, her fellow villagers would have considered Tamam special. The measure of her merit – like so much else in any Arab community – depends on her family esteem.

Tamam is a Sarkis, the most powerful clan in Ain Kfar Zabed. The nine hundred inhabitants of the village belong to one of four clans: Sarkis, Hakim, Hinde, who are Christian and are sixty percent of the population, or Sahle, who with some smaller families make up the Shi’a Muslim remaining forty percent. The Sarkis clan dates as far back as the village itself – which is only about one hundred years, as best one can judge from contradictory accounts of village history. The patriarchs of the four clans grandfather, great-grandfather, or great-great grandfather to just about every inhabitant of Ain Kfar Zabed today – gradually bought out the fields surrounding the village where they had once been fellahin, quasi-serfs to the Abou Khader family, large landowners from Zahle, the nearest city. (An Abou Khader today sits in the Lebanese Parliament.)

Moreover, Tamam’s family has the longest history of “embourgeoisement.” Her parents are relatively big landowners in the village. So big that they even employ workers from outside the family. Day laborers are always Muslim, either from Ain Kfar Zabed itself or from the neighboring village of Bedouins, who twenty years ago decided to stop being nomads and settle down in their own village. The men get ten Lebanese pounds a day ($3); the women, six pounds ($2).

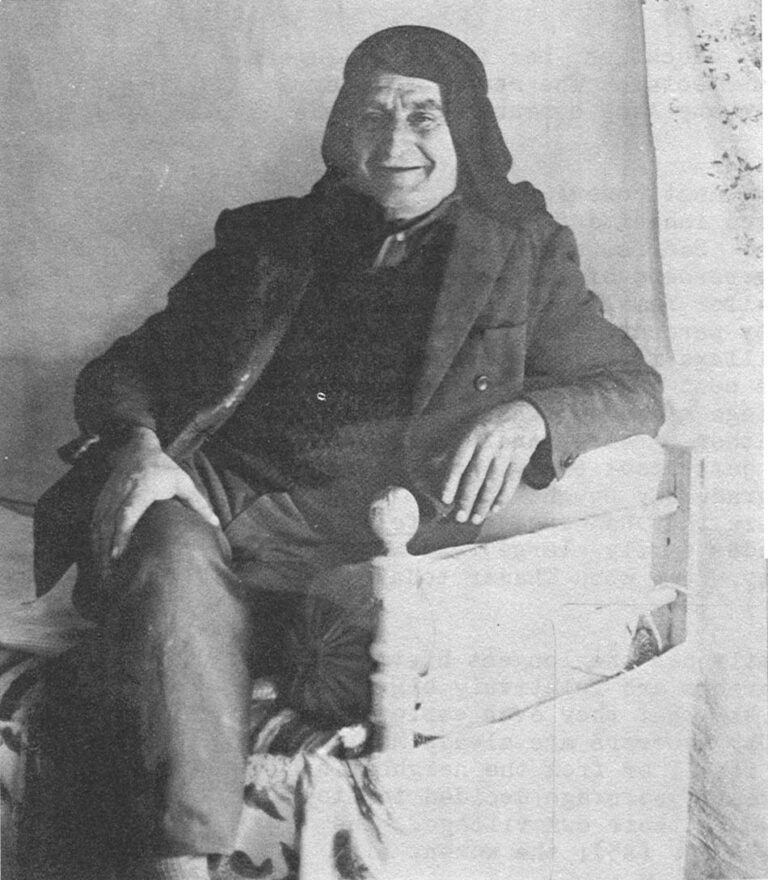

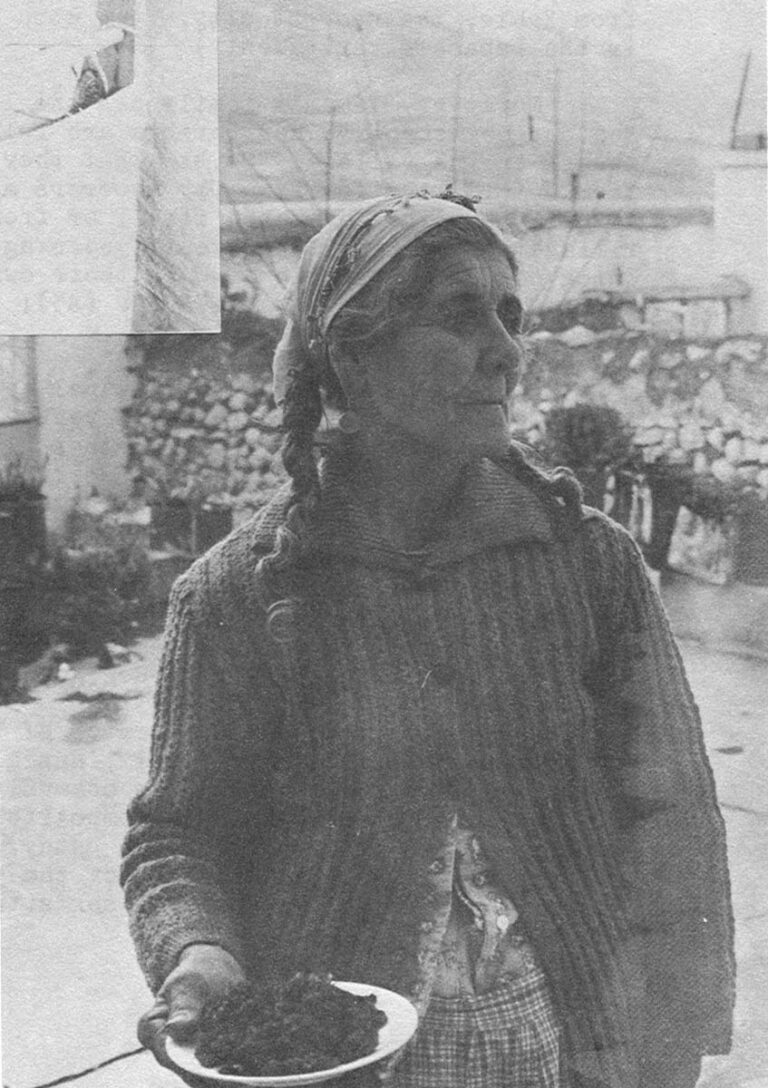

Employing laborers was a natural decision. Tamam’s father, Abou George Sarkis, age seventy, is too tired to work the fields. So is her mother, Im George Sarkis, age sixty-five, whose child-like spirit and peasant pigtails seem to mock her deep wrinkles and her even more profound fatigue. In addition, seven of Im George’s nine living children are girls, who inherit neither the duties nor privileges of the land. Elias, her second son, age thirty-three, escaped the drudgery of the fields twelve years ago and joined the Lebanese gendarmerie. This left only the eldest son, George, to work the fields.

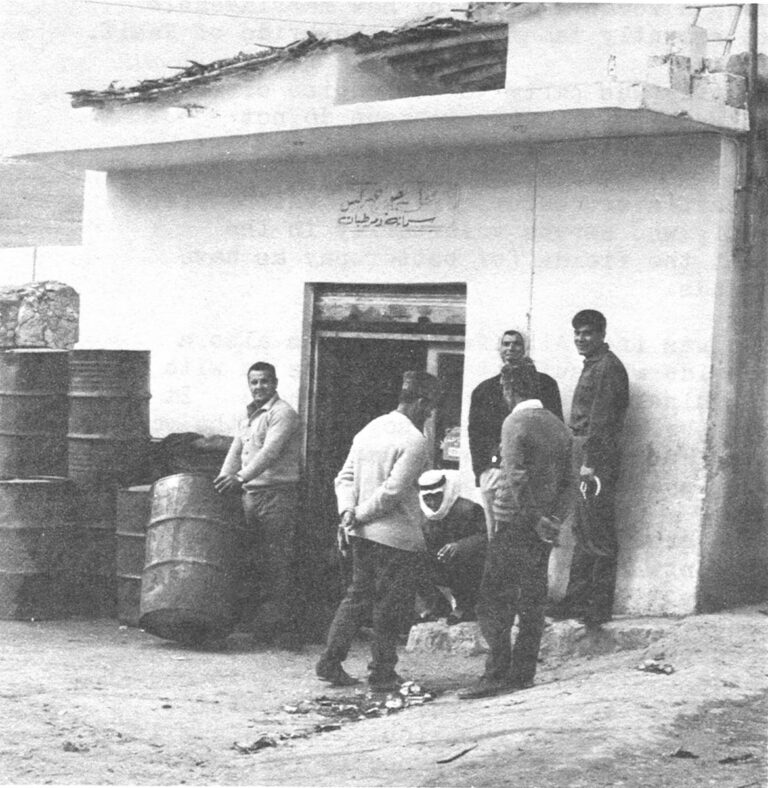

George, however, opted in favor of his own style of embourgeoisement and, as a result, has also boosted family income and power. He opened the community’s first store. (Twelve years later, he has two competitors.) His dukkan (general store) offers groceries, candy, beverages, as well as several billiard tables for the young men’s evening entertainment while the opposite sex sits at home.

George also stocks notebooks for the children who attend his private grammar school, taught by five young women commuting from Zahle. (There is another school – government sponsored – which is not as well attended because, says Mademoiselle Chidiac, who is a Maronite Christian, the villagers – both Muslim and Christian – prefer the discipline and prestige of education by Christian hands provided by George’s school.)

*More significant for family esteem is the fact that George holds the most important position in the village, Mukhtar – mayor cum chief. His dynamic, jovial personality and facile serviceability (as well as his family’s wealth) qualified him for the office, which he won eight years ago on the ticket of a regional boss

The fact that Tamam’s family has close relatives in the United States also contributes to her distinction in the village. (The relatives, who live in Rochester, New York, donated money which Mademoiselle Chidiac had solicited for the Center, further tying Tamam’s family to the Center.)

Tamam’s sisters have all married well, another source of family pride. Two who married village boys moved to larger towns nearby and moved up in status thereby, two others married men who remain in the village but who hold jobs one notch above working in the fields. One still does farm labor, but on a salary basis and in a quasi-governmental institution, the Ford Foundation’s experimental farm in the village of Turbol. The other brother-in-law works for the electricity company two weeks a month and receives the same income as if he worked full-time in the fields; plus he has the prestige of a job which is more sophisticated than farming.

Tamam – benefiting from her sisters’ match-making experience, her family’s reputation in the community, and her own unique qualities thanks to her contact with the Center – is an exceptional girl. “A good bride” villagers would call her using the complimentary expression in Arab society, which measures a woman’s merit by how marriageable she is. Indeed, just recently Tamam became the bride of Nasif.

Tamam’s entire family was party to her choice of a mate. They considered Nasif’s religion. (Christians do not intermarry with Muslims.) He passed that test.

They examined Nasif’s economic prospects, which were also acceptable. Nasif, who serves voluntarily in the Lebanese Army, has quit the fields for better pay as have Tamam’s sisters’ husbands.

Whether or not he was from Ain Kfar Zabed was also a vital question. The bride who automatically moves in with her groom’s family is vulnerable in her new household. It is thus preferable for the bride to marry someone in the village close to her own family, who can ally with her in case of in-law trouble. Nasif is a follow villager

“Gentility” of the groom’s family is also a consideration. When asked to define “gentility,” villagers stress compatibility between bride and in-laws. This is important since the bride takes up residence with her groom in her in-law’s house, which often has only one communal bedroom. She lives there with her husband and eventually children until there is enough money to establish an independent household. (One outside observer suggested that the average duration with in-laws is ten years.) This is one reason why young people remain engaged five or more years before marriage, accumulating money. Also in Ain Kfar Zabed, many young men like Nasif have a five year wait between the time they are eighteen and can join the army or gendarmerie and the time they can receive official permission to marry.

Nasif sees Tamam once a week – actually only one evening a week since he spends most of his one day, army furlough visiting friends and family. In effect, Tamam is married more to her mother-in-law than to her husband. And unfortunately,

the one quality that was overlooked in considering Nasif as a mate was his family’s compatibility with Tamam. Ever since she moved in, Tamam has had a running battle with her mother-in-law.

Im Shahin, a heavy, buxom woman, is Nasif’s mother and Ain Kfar Zabed’s answer to Mrs. Portnoy. She dominates her diminutive husband and sons. In her ultra-neat home, she affects bourgeois airs as she serves her guests gold-wrapped, chocolate bon bons from a triple deck, aluminum tray.

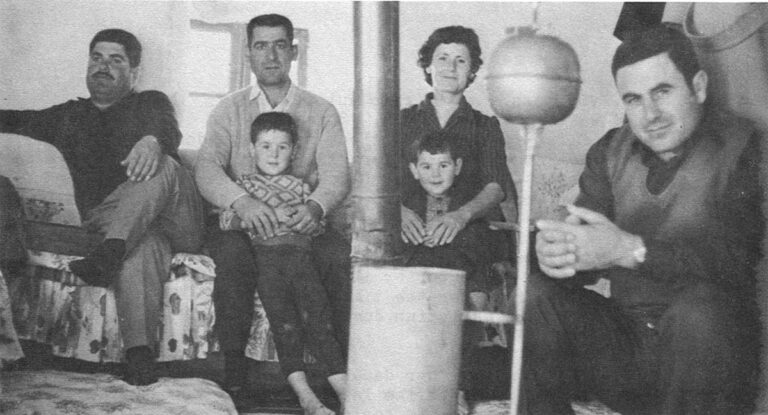

One of Im Shahin’s favorite topics of conversation is her son, Mansour. He lives in one of the village’s newer, concrete houses and has one of the village’s three television sets. He is truly master of his twenty-six year old wife and their six children; they have been trained to obediently file in and say “bon soir” to Mansour’s guests, who sit in traditional fashion – cross-legged and in stocking feet on the floor – watching the television and whose entire French vocabulary consists of “bon soir.”

Older women like Im Shahin openly admit that they want their sons to marry so they can have a daughter-in-law to keep them company and help with the housework. The daughter-in-law serves in some ways as a handmaid to her mother-in-law. The older woman remains boss of the household; the bride is a useful helper.

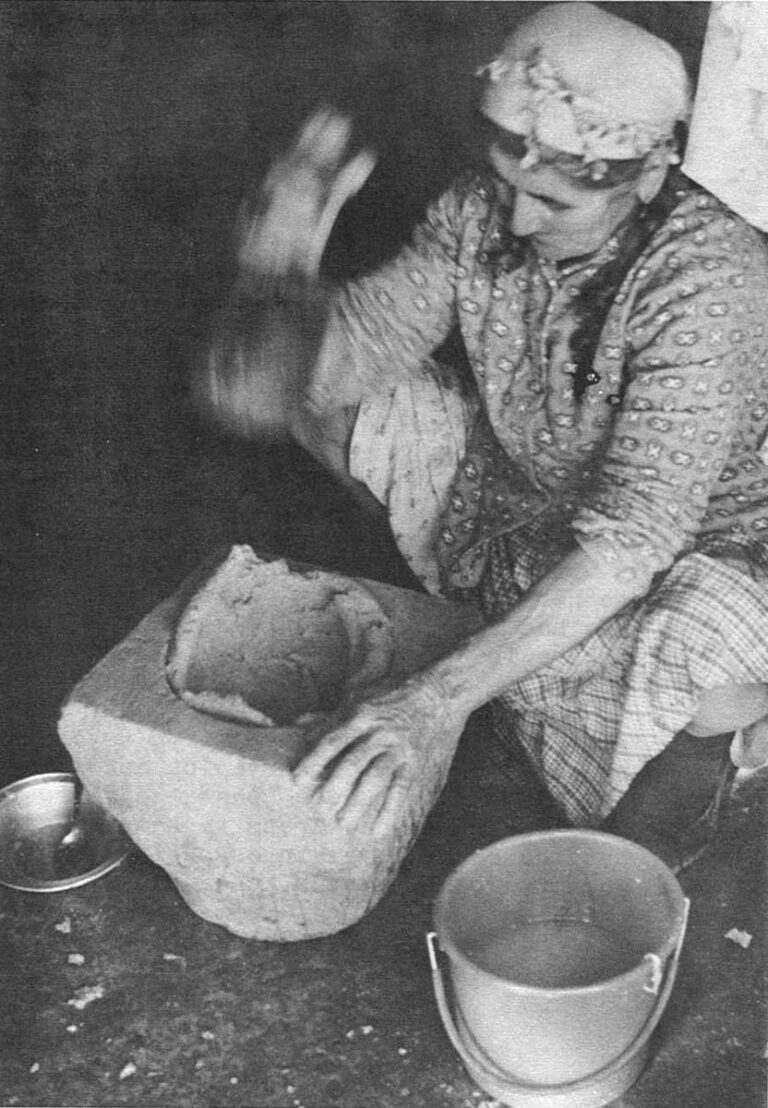

The division of labor is clear in bread making, the most vital domestic activity in the village. One day each week the head woman of each household bakes enough bread for her entire family for a week. She uses the family bakery – a small, smoky lean-to equipped with an earthen, hemispheric structure over which the dough is stretched to cook for three minutes until crisp.

The mother-in-law of Debe, Tamam’s twenty-three year old sister, bakes bread every Friday. She has the prerogative of throwing the bread dough in the air, stretching it across her arms until it is about two feet in diameter, placing in on a pillow, and flipping it onto the oven. Debe, having married last year and moved in with her mother-in-law, with whom she is quite compatible, is the next eldest female. So Debe’s task is to sit beside the older woman and pat the dough, preparing it for the virtuoso, bread-tossing performance. A younger girl feeds the fire with straw.

The mother-in-law of Debe, Tamam’s twenty-three year old sister, bakes bread every Friday. She has the prerogative of throwing the bread dough in the air, stretching it across her arms until it is about two feet in diameter, placing in on a pillow, and flipping it onto the oven. Debe, having married last year and moved in with her mother-in-law, with whom she is quite compatible, is the next eldest female. So Debe’s task is to sit beside the older woman and pat the dough, preparing it for the virtuoso, bread-tossing performance. A younger girl feeds the fire with straw.

Tamam understands that she must assume her proper place in Im Shahin’s household hierarchy. But Im Shahin is a difficult woman to live with. She is the type who pushes for perfection even at praying. (According to Soeur Helene, a nun who teaches the catechism to the villagers, Im Shahin was the most pious of all at Christmas Eve services, where for one solid hour she sat beating her breast and looking up to heaven.)

Im Shahin constantly criticizes Tamam. And Tamam does not passively submit to her mother-in-law’s dictates. The latest round in their battle started when Im Shahin demanded that Tamam quit her job at the clinic. Tamam refused. Then Im Shahin demanded that Tamam turn over her salary to her. Tamam refused again. (But she gives the money to her husband, who in turn dutifully submits it to his mother.)

Im Shahin can not tolerate Tamam’s obstinance and insubordination. The older woman is spreading rumors in the village about her daughter-in-law. She accuses Tamam of causing the expulsion of Nadia, Im Shahin’s granddaughter, from the Center school. But Mademoiselle Chidiac, the Directress, says that she expelled Nadia for repeatedly “saying words against” Madame Samira, the dressmaking teacher.

Mademoiselle Chidiac, who with the nuns at the Center sometimes serves as village arbiter, has become involved in the family crisis. She views the problem as the right and dignity of a woman, Tamam, to express herself independently. But she realizes it is wiser to remain quiet concerning her viewpoint. Rather she is intervening to get Mukhtar George to come to his sister’s assistance versus her in-laws. She is appealing to George’s traditional responsibility as eldest in his family to protect his sister.

Tamam – to put it in blunt “sociologics” – is a traditional, village female caught in the crosscurrents of modernization introduced by the Center. Her training is a mixed blessing. It has given her functional skills in health and home making and eventually a salary. But the self-confidence, which she has acquired, makes her seem headstrong compared to the customary, obedient behavior of girls her age. She has begun to doubt fundamental matters that her predecessors and even peers accept without questioning. She is re-examining the traditional, rural, Arab woman’s role in society, which is to carry on the family line and increase its size.

Increasing family size augments family power, and the family is everything in the village – structure and superstructure. The family effects every aspect of a villager’s life. It influences his thinking and how he views others around him. When one villager addresses another, for example, he does not say “Oh Aziz,” but rather, “Oh my son of my paternal uncle.”

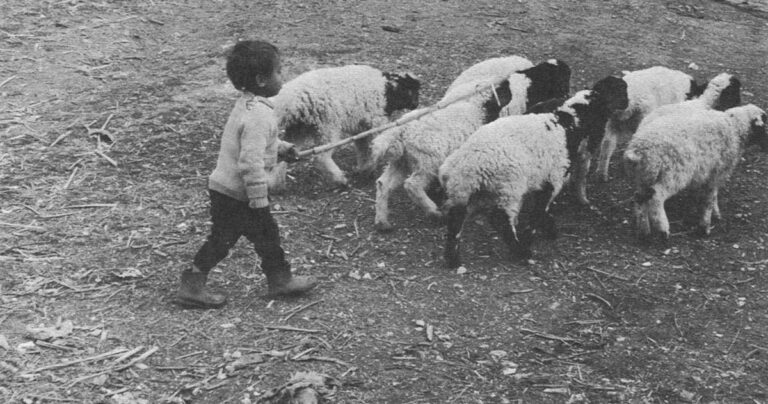

The family provides the manpower to keep the village economy running. Working the fields or building a house is a family affair. The more children, the more workers. The more children, the more secure one’s old age will be. (Actually, male not female, children are considered economic assets. A male can earn a living while social dictates make a girl an economic liability by confining her to the home where she works as hard as a man but does not add to family income.)

The family also sustains each member socially, warding off the first hint of alienation. Except for the men with free time who bunch together in a meeting place which changes to follow the sun as it runs its course through the village and except for the young men who play at the billiard tables, in early evening, social life is a family affair.

There is no regular mealtime when the entire family congregates. Everyone munches at different hours on bread, dairy products, meat (brought from Zahte) and especially candy, fruit, and other sweets (which may help explain all the missing teeth and flashing gold when villagers smile.) Rather the social hour is between eight and ten in the evening; and in the winter, it centers around the family’s oil-fed fire.

That is how it is at Im George’s house – several, separate, one room structures built of thick, earthen walls and of straw and wood beam ceilings and connected by an open courtyard. Guests enter the room, which serves as the salon and which is decorated with calendar pictures of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ and with a crucifix that glows in the dark. Visitors shed their coats and shoes and arrange themselves on floor cushions made of bright, patterned cotton. The men usually puff on nargilehs (water pipes) and play cards. The women – those who are not at-home with the children – fetch the men sweet, Turkish coffee and water from the bareed (communal water jug) which sits in a cool, cavelike perch dug into the thick wall nearest the door.

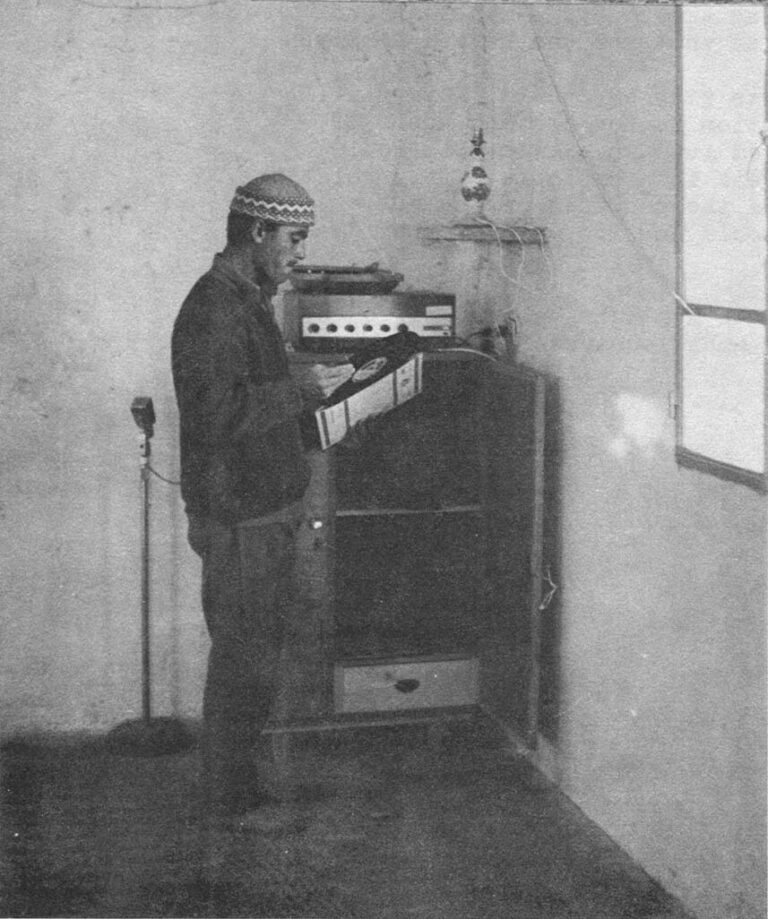

At 10:00 p.m., visitors seem to rise automatically to retire early and wake up with the sun. Sometimes, however, they listen first to the ten o’clock news, broadcast in Arabic by Kol Yisrael (The Voice of Israel), which the villagers say is more trustworthy than broadcasts of the Arab countries. (Christians in the village – sixty percent of the population – also repeatedly declare to Westerners their political preference for Israel over the “Arab” states. By “Arab,” they mean the predominantly Muslim Arab states like Syria. They dislike Syria, whose border is just a few miles from the village, for they remember the times that Syria has stirred up trouble in the Christian dominated State of Lebanon.)

During the day, Im George and her daughters replace the men around the fire and gossip about the latest romance in the village. This month’s favorite topic is Aida, a fifteen-year-old beauty, and her two competing suitors.

Producing a family like Im Georgels, which together with about one hundred and thirty other households constitutes the entire village of Ain Kfar Zabed, is obviously essential to the maintenance of the community. From this viewpoint, the female may derive some pride in her work as propagator. But after the first two or three or five or eight children, she loses inspiration.

It is quantity more than quality that counts in her job – unless you account for the fact that having a male child carries more value than having a baby girl. The mothers of Ain Kfar Zabed think they are better off than the bedouin women who, they say, bear their children at work in the fields, put their offspring in a cloth sack on their back, and return to the fields to continue working. But, in fact, the village women are not much better off.

One doctor recounted a conversation that he had with a village woman who was eight months pregnant. He commented to her that her record showed that is was just nine months before she had born a child. “What do you expect?” the woman replied. “There is nothing else to do in the village.”

Some of Tamam’s fellow students at the Center give the same reason for the high birth rate. And one may conclude based on personal observation as well as studies on the subject of women’s attitudes – that the younger generation may have more education and dress in shorter garb than their mothers, but their ideas remain essentially the same. They start accepting their traditional fate at an early age.

But not Tamam. She does not view the family through traditional eyes. Nor does she consider the sociological reasons for the family. She is looking at the subject from her own personal viewpoint.

The hard work in the village has already made Tamam, age twenty-one, look ten or more years older, especially around her eyes and in her swollen, leathery hands. She is not inclined to bear twelve children, as did her mother, Im George. One does not want to have babies non-stop, as do other women until they are physically incapable. And she does not want to suffer from the village women’s common ailment as reported by the doctor: fatigue, serious enough that women – young and old – periodically reach a point where they can not even stir from their resting places near the household fire.

Tamam wants to play the woman’s role her own way. She loves children, but she wants to have only a few that she can educate or even dress properly – unlike her nieces and nephews who run around barefoot, coughing, and noses running in the cold, wet, mid-winter weather in this village nestled between two mountains.

Tamam will openly tell Mademoiselle Chidiac, the nuns at the Center, or a foreigner that she wants no more than two or three children. She even dares to speak her mind concerning optimum family size in front of Im George and in front of her fifteen-year-old niece, who has followed in her footsteps at the school. But it is strictly taboo to say in public that she wants less children than she is physically capable of producing. Tamam believes that “in the hearts of many of the girls in the village, there may be ideas similar to mine” but she is careful not to speak for them since she nor anyone else has ever broached the subject.

Tamam told Nasif that she wants only two children. He wants more. They got married five months ago. She is five months pregnant. Tamam declares, however, that from now on she will be master of her own fate. She will take “the Pill.”

(“Village women take the Pill,” reports Mademoiselle Chidiac. Asked how that could be when the average family seems to have ten children, she replied, “If the women did not take the pill for a month after childbirth, the numbers would reach fourteen or so per family.” Tamam, however, is the only village woman making a connection in her mind between “‘the Pill” and family planning.)

Tamam says she will not tell Nasif when she starts taking “the Pill.” But Soeur Adele, the nurse whom Tamam assists at the clinic, knows village life and knows that new news is at such a premium in the quiet village that Tamam is cherishing her secret, waiting for the day to tell it. “One amorous night,” says Soeur Adele authoritatively; “Tamam will tell Nasif.”

And Nasif will hit the roof. But the real problem will not be Nasif; it will be his mother, Im Shahin. Tamam is in some way duty-bound to her in-laws to propagate their family line. Taking the pill is a radical deviation from the behavior expected of her. It will climax the battle between Tamam and her mother-in-law.

The crisis, according to Tamam’s projection, will have two alternate resolutions, depending on who will win.

If Im Shahin wins, Tamam will follow the traditional path, abandon the idea of family planning, and have babies non-stop. She will take on the village woman’s attitude and slouch: sitting with legs stretched out under a long but thin and revealing cotton skirt and with sagging stomach muscles permanently stretched out of shape. (It is a waste of time, apparently, to exercise for muscle tone after a pregnancy since another baby will be coming along soon.)

If her first child is a boy, she will follow the custom of changing her name to Im (Mother) So and So: Nasif will become Abou (Father) So and So. If the baby is a girl, they will not bother and wait until a boy comes along before changing their names. And if the baby is a boy, Tamam will pin a blue bead to his clothes to protect him from the evil eye; if it is a girl, she will not bother – unless the girl is an exceptionally beautiful, healthy, and strong baby.

In other ways, a girl will learn to expect lesser treatment than boys. She will learn to serve the men folk – older and younger than her – without uttering a word of dissent. She will learn to cook and clean. And when fifteen or so, she will begin looking around for a man in whose house she will marry and with whom she can have a family.

If Tamam wins her battle with Im Shahin, things will be different. Tamam’s solution is for her and Nasif to make their own home away from in-laws. Since this would constitute an unorthodox break in acceptable family relations, it could only happen outside the confines of the village. It means the young couple would have to immigrate to the big city, Beirut.

So comes social change to Ain Kfar Zabed. So go the village’s most talented and ambitious women.

Received in New York February 19, 1971.

©1971 Paula Stern

Paula Stern, a free-lance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Stern and the Alicia Patterson Fund.