Garlic and olive oil and plenty of hugs in the sunshine. They stick in my mind as keys to healing after three days of listening to workshops at the Second New England Healing Arts Fair in May in Greenville, N.H. The workshops covered everything from herbal healing and menstruation to body purification and diagnosis by iris examination (iridology).

One workshop leader vowed that a man who couldn’t swallow was “fed” by attendants painting olive oil over his body enabling him to live eight years on the nutrients absorbed through his skin. I found that hard to believe, but he said it was true.

Another workshop leader, known as Herbal Ed, used five cloves of garlic every morning in his breakfast tonic. He called garlic Russian penicillin and the most universal remedy in the world because it kills harmful bacteria and spares the friendly. Here is his recipe for those who want a combination of Dr. Stone’s liver flush and Vermont folk remedies for morning purification.

12 ounces Rejuvelac (water soaked 24 hours in fermented wheat berries).

4-5 garlic cloves

1 tsp. honey uncooked

1 tsp. apple cider vinegar

1 tsp. olive oil

1/4 tsp. Nigerian cayenne (Ed uses a full teaspoon but recommends less for beginners).

Whip in a blender two minutes and drink slowly.

He said the mixture tastes like salad dressing. I haven’t felt compelled to try it myself, but I want to pass it along in the interests of self-care.

Healing arts fairs abound in the West but are only just getting started in the East as a place for people practicing alternative lifestyles and methods of healing to gather.

The fair I attended was based at Another Place, an alternative conference center in a large 18th century house surrounded by fields, apple trees, a brook and a pine grove about one hour and a half from Boston. The center charges admission on a sliding scale according to salary figured on the honor system. I paid $12 daily for the workshops, three vegetarian meals and a tent site where I was told I’d have “more personal space” than in the crowded house.

I realized when I arrived how straight and square my lifestyle is. I work a straight job, I eat meat, I drink milk or “do dairy,” and wear my shoes in the house. I also have never heard of iridology, rebirthing or played with an earthball (until the fair). And I don’t eat with bowl and chopsticks three meals a day as did many of my fellow fairgoers who brought their own sticks and bowls. Chopsticks help you eat more slowly and avoid an American habit I haven’t shaken yet of eating too fast.

My first two days at Another Place I was in slight culture shock, now that I look back on it. I am 38, and I didn’t fit in with the lifestyles of the more than 70 – double that by the weekend – young people who came from all over New England for the fair. They hitchhiked or carpooled. Most seemed to be vegetarian. One young man mentioned to me that he knew it was wrong but if he saw a piece of steak in a pan he wanted it. He still hadn’t been able to lick the meat desire. As far as jobs go, I know one young woman was jobless and another just fired from her health food store clerk’s job over a management policy dispute, and a third was a masseuse in a YWCA.

I cheered up the last day. After a lunch featuring a glorious gazpacho soup, I took a sweat bath followed by a bracing hose down and a steady, stretching backlift with Herbal Ed. Then I underwent a “feather treatment” from a white medicine man which left me smiling. Good things come in threes – and more. Once I felt good, I got more – some surprise gifts: a book, some medicine tonic for anger made from vodka and herbs, and a card, and best of all some healing hugs from some fellow fairgoers and the medicine man.

I left feeling much more part of the fair than the observer I was on arrival.

Here are some impressions of the fair, notes from workshops and statements from workshop leaders, none of which I have verified but which exposed me to herb study for the first time. This ancient art is practiced in my newspaper’s home community of Lawrence and I have never been properly aware of it to give it a line of print, even though I was the health reporter. Herbalists flourish among the Spanish-speaking population of 13,000. A social worker in the community told me that some of the Spanish-speaking on medicaid have a hard time getting doctors because few doctors will take them as patients so naturally they rely on herbalists.

Pasteurized cow’s milk was not regarded as the perfect food at Another-Place despite the National Dairy Council. Herbal Ed noted that someone fed a nursing calf heated milk, and the calf died. Raw goat’s milk was considered OK, and yogurt, too.

So my first breakfast I saw no milk for my oatmeal. Delicious raisins, nuts, dark honey yes, and yogurt, but no milk to wash it down. I ate it without, but I was going against an old habit. Later I learned from Bill, the coordinator, that there was milk in the refrigerator for closet milk drinkers like me, but I had been reluctant to ask and eager to do as the group was doing.

The flyer advertising the fair emphasized that healing comes through work – cooking, dishwashing, making signs or caring for children. It turned out during morning meeting before the workshops that the hardest job to fill was child care to give parents, most of whom were single and without help, a chance to attend the morning and afternoon workshops.

Bill had to come down hard during these meetings to recruit child care volunteers. The meetings started in meditation, all close and quiet, holding hands and sitting cross-legged in a circle. Then came the other reality – the morning work slots weren’t filled. It appeared that the instant commune for healing had the same work coverage problems any other group has.

I volunteered once to cook supper. That meant I had to leave a workshop on menstruation while a midwife was talking about scented tampons as a big business plot to sell more by artificially increasing blood flow and lengthening periods. You could wonder what I was doing at such a workshop. I have two daughters and a wife and want to understand more of their lives and I didn’t know when I’d get a chance again to hear other women talk openly about menstruation.

Anyway, I was off to the kitchen where I got assigned the salad dressing. Two bowls would be enough for the 70 persons expected. I decided quickly to make the only salad dressing I know which is vinegar and oil with mustard powder and salt and ground pepper.

Bill told me olive oil was too expensive to use alone and that I should cut it with a lesser oil. I found plenty of apple cider vinegar with the cloudy “mother” in it that made it just right according to Herbal Ed.

Then I shook the mustard into one of the bowls. A skinny young woman was preparing the greens beside me. I knew she had three years experience studying herbs.

“Yuck!” she said. “Mustard puts holes in your stomach.”

I stopped shaking the mustard. I was afraid not to. “How about salt? How is that?” I asked, put off and feeling I had violated a rule of natural food wisdom I never knew existed.

“Salt we don’t need,” she said firmly. So I said the heck with it and left the second bowl straight oil and vinegar.

I was acquainted with the young woman. It is the ecological, policy of Another Place to have no car traveling to conferences empty of passengers, and she had been my rider. On the drive she told me horrors of worms in fish she had bought at the same fish market I trade at, her fears about radiation and information that organic banana skins turn black evenly instead of becoming spotted. She knew plenty that I didn’t know, though she seemed overly fearful of living in 1977. Her manner was abrupt with me, and I hadn’t realized that mustard was on her hit list.

When I returned to the menstruation class, Nancy Fry, the leader and a masseuse from Hartford, Conn., was talking about calcium deficiency during menstruation. She opposed drinking cow’s milk for calcium and as a substitute suggested sardines, seaweed, mustard greens, lamb’s quarters (a vegetable), asparagus, cauliflower, cabbage, beets, sprouts, lemons, onions and scallions. She said her period had become shorter in the eight years she has eaten vegetarian.

She demonstrated a massage to relieve menstrual discomfort. It included rubbing the cervical acupuncture point on the big toe, the Achilles tendon area and the abdomen, all of which can be self massaged. That morning I heard from Herbal Ed Smith, already mentioned several times, who did the most continuous talking about herbs and body purification and was a commanding lecturer. I don’t know the validity of his statements as I pass them on and can only say to the skeptical, “Listen.”

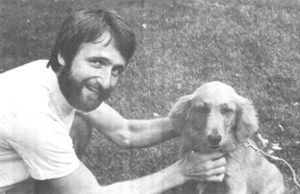

Smith is a slight man of 32 with a blonde beard and glasses and a passion for keeping himself cleaned out. Nasal douches, sweat baths, enemas, vomiting and plenty of garlic and oil are among his methods. He was fond of saying Americans overuse soap by removing skin oils in their fear of stinking and then totally neglect internal cleanliness and getting rid of the “gookies” (Smith’s word for the fecal unmentionables and other impurities within).

He opened his workshop with everyone sounding the Sanskrit “om”. Then he told us that whatever mystical benefits om provided, more importantly it had healthful effects by vibrating the pituitary.

He got interested in herbs six years ago while he was traveling in Colombia, South America. He met a shaman from whom he learned a lot about herbs and vomiting. He also learned by talking with herb women in the market and reading everything he could find on herbs. He now works at the Hippocrates Health Institute in Boston which uses a raw food vegetarian diet featuring wheat grass juice. Many cancer patients go there. Smith is a health counselor, lecturer (the Institute is run like a school not a hospita1) and gives massages.

He hit on one of his favorite themes in workshops: “The body is 35,000 miles of pipes. It’s a plumber’s nightmare. It can become clogged. We need some organic Drano to clean it out.”

He suggested the herb Goldenseal for mucus membranes because it is toxic. He said the colon and the large intestines are repositories for about 10 to 20 pounds of old fecal matter. He called the large intestine “a cesspool” and said the “barnacles of waste” clinging to it can be removed by bayberry bark and white oak bark enemas.

I am still at this point an enema virgin, and the prospect of internal purity was looking dimmer as Smith talked.

Smith fasts one day a week with a three-day fast every fourth week and every fourth month a 5-to-10day fast. He said he has taught the art of receiving enemas to middle aged women at the Institute and that it is a learning process, like anything else. The Institute is big on interior flushing.

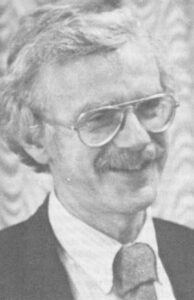

Ken Cadigan, 33, another workshop leader at the fair, was lecturing on iridology or iris diagnosis. A slide of his right eye was projected on a bedsheet hanging in the peak of the attic at Another Place while 20 persons watched. He said each iris was as unique as a fingerprint and that piles of information could be read from it. He passed out charts showing that the iris is divided into sections corresponding to various organs and body parts. The guru in the country on iridology is Bernard Jensen, a chiropractor and naturopath from Escondido, Ca., who says that there are basically only blue and brown eyes and that all other colors indicate a problem. Green, like my eyes, indicates too much sulfur, Cadigan said.

He pointed to a section on the slide with black spots and said the spots indicated he had worms in his large intestine.

“Everybody has worms,” Cadigan said reassuringly. But they (the worms) don’t like cayenne and garlic.” He said he had begun his health regime 25 pounds overweight. Recently after a 21-day beet and carrot juice fast he produced a 14-inch tape worm. When he went to tell “Dr. Ann” (Ann Wigmore, doctor of divinity and Hippocrates-founder and director) what had happened, she was unimpressed. “That was a short one,” she said. Cadigan figures that a 21-day fast is only a drop in the bucket toward his internal flushing which he expects to take up to seven years.

Herbal Ed lectured in the squatting position, Third-World style with buttocks against heels. He said that if Americans defecated that way they wouldn’t have hemorrhoids. He tossed off the healing agents – air, light, earth, energy (ether or vibrations), touch and love.

“In disease we have to supply a missing element in the body and free the obstruction,” he said. “We don’t heal ourselves. We let it happen.”

He said his Institute uses implants of wheat grass juice into the large intestine. Sometimes they will implant a fresh colony of friendly bacteria equipped with whey powder in which the bacteria flourish. “It’s like sending the bacteria in with a box lunch,” he said.

Smith had set up his jeep as the first aid station of the fair. From it he sold ounce containers of “Herbal Ed’s Healing Salve” for $3 each. He had made the salve from his own mixture of olive oil, comfrey root, mullein, St. Johns Wort, chickweed, marigold, marshmallow, plantain and bee’s wax. It was selling fast, and people were finding it gave them relief from multiple black fly bites. The May crop of black flies which hung in clouds around our heads had arrived punctually.

Bean sprouts are a top food for Smith who says they are far more digestible than beans. Sprouting is easy and can be done indoors on bakers’ trays. He said he had sprouted beans in a nylon sock in the dark of his pack while walking in South America, occasionally dunking the sock when he came to a stream.

He visited Vilcabamba, Ecuador, known for its long-living inhabitants. He was distressed to find in that town of perfect climate and temperature never rising above 85 that CARE package imports of white flour and white sugar were ruining their diet.

He is spending this summer at a water therapy clinic run by the Seventh Day Adventists in the Ozark Mountains. He is interested in olive oil applications, long sunbaths and clay therapy. The clinic is used mainly by old people. Smith concluded: “There are no incurable diseases, only incurable people…everything can be healed.”

My third day at the fair was best for me. It began with a Japanese tea ceremony which helps make the ordinary fresh and strange. Ken Cadigan’s workshop was packed with information that morning and he concluded with a sane but grim warning: “Nothing is organic or pure anymore.” He said since pollution has reached everywhere, the only thing is to accept that and aim towards the pure not demand it.

After a lunch of gazpacho soup and sprouts, I climbed down to the field below the house for a sweat bath. It looked like a mini-nudist colony. About a dozen bathers were massaging one another on open sleeping bags or cooling off with the hose. The sweat lodges were igloo-shaped tents with plastic tarps and canvases draped over bent saplings to hold the heat from the stones. I stripped, laid my clothes and notebook on a brush pile and crawled into the lodge with the liveliest chanting.

“Hurry up. Don’t let the heat out. Close the tarp behind you,” said one of the four women cross-legged on the grass floor. It was Jocelyn Stamp on my left, a masseuse with the Joy of Movement Center in Boston. The first day of the fair after an herbal workshop she had come to me to ask if there were anything bothering my right heel. She said she had a sense of something in pain. She had been sitting across the circle from me and I had my heel covered with shoe and sock.

I have a sore Achilles tendon on the right that has kept me from jogging which has been a ‘depressing loss to my freedom of movement, so when she brought up the subject I was listening carefully. Unfortunately she didn’t say much, only that she’d like to work with me but she seemed never to have the time. I was intrigued by her sensing my heel.

Now in the lodge we took turns passing a plastic jug and flicking cold water on our faces and onto the stones steaming in a hole cut in the center. Each bit of water on the stones brought a wave of heat to my head and shoulders. Eucalyptus oil mixed with the vapor and felt good and clearing in my sinuses.

Ms. Stamp, who is South African, led what sounded like a South African chant while at the same time squeezing and probing our arms, one after the other in a forceful but tension-easing massage.

When she came to me she rubbed my forehead, first slowly, then faster. It was a deft motion. I felt knots of tension pour into her hand. I really let go. The tight muscles around my eyes loosened, and my jaw dropped. The five of us held hands and chanted while the sweat beaded and dripped off us. I wasn’t thinking about anything or worrying – maybe this was an indirect way to help my Achilles tendon. If not, it was certainly relaxing.

After a while we had had enough and crawled single file back into the sun. We sprayed each other with the hose. Ms. Stamp insisting on dousing the bottoms of feet. We breathed out and whooped to take the exhilarating shock. It was similar to saunas I have been in except the setting of pines and grassy fields was more lovely.

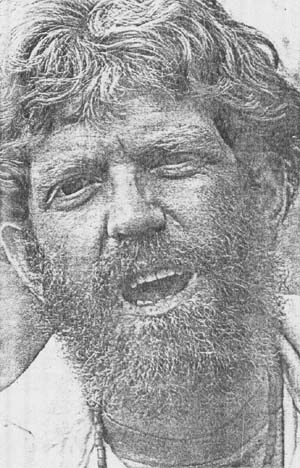

My last workshop was led by Wayne Tashea, a self-described “cowboy” and “medicine man” from Connecticut who talked about sight diagnosis. Example – “Examine the ridges on your fingernails. Short lines show a critical person. An indentation means something happened to you recently,” he said.

He talked fast relating some unconnected information such as a recipe for a bath to protect one from X-rays. It required one pound of sea salt and one pound of baking soda in the bath, and he said it would neutralize radiation if you soaked in it for 15 minutes, breathing through a tube to get your head wet.

A bulbous nose shows an enlarged heart, a cleft in the chin a sentimental person, he said. Peaked eyebrows indicate a person worries about money. Hair between the eyes shows the person eats much meat and sugar. He said the tongue can be a diagnosis point for the whole body, with tongue areas corresponding to organs. We had already heard about food and iris diagnosis. Tashea, who is studying acupuncture, said that an experienced acupuncturist can feel more than 20 pulses on the wrist and diagnose a person’s condition without examining further.

After the workshop he told me that before he had traveled the healing fair circuit, he had been a body guard, a nightclub manager, a yacht captain and maitre d’ and that he had been kicked out of college and the military. He was 28.

The feather in his straw cowboy hat was a gift and that made it “strong medicine,” he said. He invited me to try an experiment, lying face up on his red blanket while he waved his feather back and forth so fast that it whirred all around me but didn’t touch me. He asked me first to remove my belt and wrist watch which he said could weaken me. He outlined my body with the feather,.not missing a spot. When he was done I told him I felt fine.

He didn’t believe me and said to rest a while before sitting. As I rose to a sitting position, I felt slightly dizzy. I began talking with Tashea and felt giggly and high, reminiscent of marijuana. He told me not to get up and did some more feather waving while an onlooker cried, “Give him another hit.”

Whatever the feather did, something was having a definite effect on me, and it was pleasant. Tashea asked what I noticed.

“The clouds,” I replied. “They’re beautiful. And the faces of these nice people. (A crowd encircled us). They’re beautiful, too.” I finally got up, feeling mellow. Tashea said he wanted to show how my leather belt weakened me. I extended my right arm, and he pushed down at my wrist. My arm stayed straight. My left arm hung down naturally with my hand empty. Then he placed the belt in my left hand and pushed on my extended right arm. It went down. Proof that the belt weakens? I don’t know. Tashea said if it had beads on it or tooling or something Indian it would have been okay.

At home my brother-in-law who is an internist was skeptical. He said the test would be more scientific using a graduated spring scale to measure the force on the right arm.

In leaving the fair I had a swirl of impressions. I tried to relate breakfas t garlic-tonic, sweat baths and feathers to the process of self-care in health. To me the important point of the fair was that these people took responsibility for their own health and practiced self-care. They broadened my horizons with new exposure to herbs and different lifestyles.

As I left it was clear to me that Tashea’s feather medicine had done its work. I felt a glow on my cheeks left over from the feather. I felt good and happy about the fair, and the people in it.

Tashea and I hugged each other.

“You won’t realize the meaning of this for three days,” he said.

I don’t know if I ever did. There have been no revelations. All I recall is that three days later it was May 9 when a freak snowstorm hit the Boston area, and I felt relaxed about it. That was good enough for me.

Received in New York on June 9, 1977

©1977 Phil Weld, Jr.

Phil Weld, Jr. is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. His fellowship subject is the role of self-care in health: a look at prevention, patient education and patient power in the U.S. and Canada. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Weld as a Fellow of the Alicia Patterson Foundation and to the Lawrence Eagle-Tribune. The views expressed by the author in this newsletter are not necessarily the views of the Foundation.