In July 1948, a young unemployed Palestinian heard that teachers were being recruited in Jordan for Kuwait. Hani Kaddumi had left Jaffa during the fighting and was desperate for work. He rushed to Amman only to find that the recruiter had left the previous day. Unwilling to give up, the former employee in the British mandate passport office in Jaffa sent a cable: “To the ruler of Kuwait: I am offering my services to work in the area of passports and immigration. I can also teach English, Arabic or mathematics.” One month later a friend rushed breathlessly into his home with the reply: “You are offered the position of Director of Passports and Immigration in Kuwait.”

Thus Hani Kaddumi arrived in the dusty backwater of Kuwait in August 1948, among the first of several waves of Palestinians who would help shape its development from a desert oasis into an ultramodern boom state. Today he is a millionaire. And there are 200,000 Palestinians in Kuwait, a fifth of the country’s population. Their situation provides an unusual insight into the Palestinian problem, which remains at the heart of the Middle East conflict.

For the Palestinians of Kuwait do not live in tents. Many of them are well-to-do professionals, company managers, and government employees. As one western diplomat in Kuwait told me, “The Kuwaitis may control the country but the Palestinians are the grease which makes it run.” Despite this apparent security, however, the Palestinians of Kuwait remain unassimilated politically and socially. Many, especially those who arrived after the 1967 war, live in relative poverty.

Why have the Palestinians, an industrious, well-educated minority, been unable to assimilate happily into the Arab country with the highest per capital income in the world? And would they return if a peace settlement led to a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Jordan, the proposal often mentioned as a possible answer to the Palestine problem?

Any Palestinian here will tell you he would never forget his homeland. But most will readily admit that the nature of Kuwait itself would make it difficult to forget, even had they wished to do so.

The Refugees Arrive

The first wave of Palestinians started immediately after the 1948 war, coming mainly from the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan where the largest number of refugees had settled and there was little work. They were trip-pioneers; Kuwait at that time was mostly desert. Hani Kaddumi built his ministry from scratch, bringing hundreds of talented Palestinians from the West Bank to staff it, getting offices built and furniture moved, and living all the time in Spartan un-air-conditioned quarters on a diet of rice and fish and filtered water. Other early Palestinian arrivals helped develop the ministries of water, electricity and public works.

By the early sixties, Palestinian professionals were pouring in — engineers and architects, doctors and teachers, and staffers for the middle levels of the growing Kuwait bureaucracy. Many were fleeing the political upheavals in Jordan of the late 1950’s. In the sixties, Kuwait also became a haven for Palestinian laborers and skilled workers, many of them born in refugee camps. Young men would come alone to Kuwait, cluster together in groups of ten to a two-room apartment, and send the bulk of their earnings back to their families in Jordan.

“This part of the world represented an oasis of freedom.” I was told by a high Palestinian executive in one of Kuwait’s biggest industrial firms. Reclining behind a desk in a suite in one of Kuwait’s new office towers, he continued: “In spite of the hardship of life itself in Kuwait when we came, there was no visible coercion here, unlike Jordan where people felt like second class citizens in their own homes. And of course, our availability happened at a time when this country was making a great leap forward. We were the first to come in great numbers, and probably the best educated percentage-wise of any of the Arab countries. So the Palestinians became the backbone of the government and Kuwaiti private companies. As rootless persons we have had to rely basically on efficiency and hard work. We couldn’t look elsewhere.”

Life became comfortable for the Palestinians. Initially the climate was hard to take, reaching daily highs of 120 degrees during the four summer months. But gradually cars, offices and apartments became air-conditioned. Palestinians clustered heavily in three new suburbs of Kuwait City. One of them, Salmiyeh, a copy of the fashionable Palestinian area of Hamra in Beirut, became a smart apartment district, with clothing shops named Tulip and Chic Baby and Pretty Girl, record stores, and even a Wimpy Hamburger House.

West Bank state ‘yes’; recognition ‘no’ say some businessmen. | |

| Daoud Kottub, Dep. General Manager, Kuwait Shipping Co.: “I support the West Bank state idea wholeheartedly. We need a passport, an identity card, a home. But Arafat has no right to recognize Israel. We can only recognize a secular state for Moslems, Christians and Jews. The West Bank is a step in order to liberate half of Palestine.” |

| Tallal Abu Ghazallah, President of the leading firm of public accountants in the Arab world: “The Jews have to become Palestinians, to be part of that state. My ambition is to get all of Palestine, not just the West Bank…. The Jews could not get a better deal than they would get now if they settle. The US won’t be the strongest power in the world forever. When Israel faces us on her own she will lose.” |

Yet despite the opportunities here and the open Kuwaiti door many Palestinians have mixed feelings about Kuwait. This is largely due to the nature of Kuwaiti society. Rushing headlong from a desert town into an ultra modern state on a tide of oil revenues, the Kuwaitis are still extremely sensitive about their wealth, and about the role of all non-Kuwaitis in their country. Kuwaitis make up less than half of the state’s population of one million. As a result, non-Kuwaitis are not granted citizenship and cannot vote or hold office (although changes in these rules are just now coming under debate in the Kuwaiti parliament). A non-Kuwaiti cannot own a business out a Kuwaiti partner holding a 51 per cent share (there are far more Palestinian managers than company owners).

Kuwaitis get higher pay and more benefits than non-Kuwaitis holding similar jobs, a source of much resentment. “They put a newly trained Kuwaiti over me with higher pay,” complained a young Palestinian electrician with six years experience in a Kuwaiti ministry. “When I complained, my boss said ‘you’re still earning more than many Kuwaiti workers.'” A Palestinian teacher told me with mixed pride and annoyance, “The Kuwaiti students have no incentive to work; they know they’ll get a job regardless, so they lag behind. But ours have no choice so they always work hard in class.”

As more Kuwaitis finish higher education at home and, abroad, foreigners are often bumped to make way for them in a deliberate policy of “Kuwaitization”. Large numbers of Palestinian professionals are beginning to move on to the Gulf States and Iraq where the pay is higher, and in the case of Iraq, the conditions for foreigners more equitable.

All of these factors add to the Palestinian sense of insecurity, the frustration of having no permanent home to fall back on should they got tired of, or unwelcome in, Kuwait or other of the Gulf states. Few Palestinians will say they plan to stay in Kuwait forever. One told me, “All my friends say ‘I’m only staying in Kuwait for a while to save some money.’ Of course, most of them have been saying it for fifteen years.”

While the Palestinians who arrived earliest in Kuwait have longstanding close relationships with Kuwaitis, most Palestinians have little social contact with their hosts. Kuwaitis tend to live in exclusive residential districts — rows of huge two and three story stone villas, or lines of neat government apartments for the poor or middle-income earners. A Palestinian housewife in Ahmadi, the garden suburb for employees of the Kuwait Oil Co., which is somewhat integrated, told me, “We have had Kuwaiti neighbors for two years but we never visit each other. I would feel uncomfortable with them and besides they never invite us.” The neighbors are there because they replaced a Palestinian employee and this woman and her husband expect they too may soon be replaced by Kuwaitis.

For large numbers of Palestinian poor in Kuwait, the roots of alienation are economic as well as geographical. After the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, thousands of Palestinians poured into the tiny state, mainly the families of poor workers who had been sending their wages back to Jordan where they could buy far more than in Kuwait. To their credit, the Kuwaitis accepted the flood of newcomers. By 1970 the number of Palestinians in Kuwait had jumped to 147,700, more than double the 1965 level.

With the housing shortage in Kuwait, the new influx meant that two and three families were crowded into tiny flats. I visited one family of nine in the suburb of Hawalli in slum conditions little better than the refugee camps of Lebanon. Peeling four-story concrete apartment houses were crowded together, often on unpaved streets, with swarms of young children hanging from tiny-balconies or-playing in the dirt outside. Inside one building, entered through a narrow windowless corridor lit by a naked bulb. I visited the two room flat of a laborer from the West Bank. The sitting room was lined with ragged stuffed chairs, its only wall decorations a map of Palestine and a framed photo of Yasir Arafat. There was no air-conditioning, and a circular fan hung broken from the ceiling. The children slept on mats rolled down on the floor at night. The father, who left his village in Nablus in 1966 because there was no work, earns 50 Kuwaiti diners ($180 approx.) per month as an assistant in a grocery store and pays 26 KD’s for rent. He must also pay for his children’s’ schooling.

| Commando’s widow and family in slum housing |

Because of the arrival of thousands of new children of school age after 1967, the Kuwaiti government could not absorb them into its school system. So the PLO set up its own system, using Kuwaiti government schools in the heat of the afternoon and hiring its own teachers at less than one-third the salary of Kuwaiti teachers. Forty percent of Palestinian students, about 17,000 children, now attend these schools. The Kuwaiti government pays one third of the cost, about 200,000 KD’s, and the children are supposed to pay the remaining two-thirds. In reality there is a regular deficit of about 200,000 KD’s, which the PLO raises through collections from wealthy Palestinian businessmen. There is some hope in the Palestinian community that the Kuwaiti government will soon absorb more of the cost.

While Palestinian identity has been heightened by lack of integration, it has also been fortified by the existence of Palestinian resistance organizations in Kuwait since 1965. In that year, a group of Palestinian professionals in Kuwait, including an engineer named Yasir Arafat, founded a political organization known as Al Fateh, now the dominating force in the Palestine Liberation Organization. The Kuwaitis were tolerant — so long as Palestinian politics presented no challenge to the Kuwaiti government. The PLO today in Kuwait occupies an embassy-like building, flying the Palestinian flag (the more radical Marxist Palestinian splinter groups have no official presence in Kuwait).

The PLO here serves largely as a fund-raising and service organization for local Palestinians, raising money, helping young men find work, and providing for the widows and orphans of dead commandos. PLO officials are quick to assert, however, that “many” young men leave Kuwait each month for commando training in Lebanon or Syria, and that young Palestinians from Kuwait participated in several of the commando suicide raids into Israel. I met one commando’s widow, originally from a small village in the West Bank, who told me that her husband would disappear periodically for a month at a time, until one time he never returned. She, her mother, and her seven children now scrape along on contributions from the PLO and Palestinian women’s organizations. Her neighbor, an elderly man with twelve children, told me that three of his sons were with the commandoes. Both families lived in hot, overcrowded, slum-like apartments.

Talking about a West Bank State

Given their lack of roots in Kuwait and national feelings which grow stronger every year, it is not surprising that there is great interest among the Palestinians of Kuwait in the idea of a state on the West Bank and Gaza. Opinions vary, although most people accept the PLO position of a state as a first step to an ultimate — if very far off — union of Jews and Palestinians. But there is a widespread reluctance to accept the explicit recognition of Israel as a quid pro quo for a state. And there is also a growing skepticism — which eats away at any talk of compromise — that Israel will ever consider giving back the West Bank to anybody.

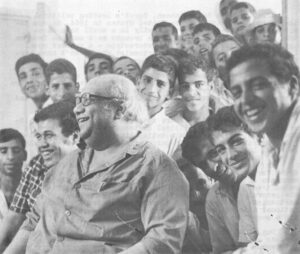

“We would accept the West Bank state because we think it is only a stage towards a unified democratic state. This wouldn’t have to happen by force. Things will change by themselves.” AbdelMohsein Cattan speaks from a deep sofa in the living room of his tasteful new villa in Kuwait, surrounded by glass and chrome and thick rugs and a huge zebra skin on one wall. Cattan, a large, vigorous Palestinian in his mid-forties who arrived in Kuwait as a teacher in 1951, is now a millionaire contractor and member of the Palestine National Council (the Palestinian parliament). In between, he was at 27, the undersecretary of the Ministry of Electricity and Water, where he built up Kuwait’s electric power system. He does not believe the Palestinians should have normal relations with an Israeli state, however, unless there are major internal changes in Israel — “the end of the Zionist idea”. “If they abandon the idea that they need 15 million Jews in Israel and say that they have nothing to do with the Jews of the world except religion: if they choose to belong to this area and stop using their influence on the United States to act against the Arab world, then I think the whole area would be open to them. Why allow an American to come here and not a Jew? Can you imagine the stupidity of such an intelligent people living in an armed ghetto when the whole area needs know-how?

| Abdell-Mohsein Cattan |

But Abdel-Mohsein Cattan, with a pessimism heard more and mare frequently among Palestinians, believes there will not be a settlement without another war, and then only if the Israelis do not win. “I predicted right after the 1973 war that they would never give up anything,” he says. “The PLO leadership argued with me, but I was right.”

Hani Kaddumi, now a wealthy businessman and member of the Palestine National Council, with two sons studying business administration and engineering abroad, twists a pencil in the silence of his modest paneled office and says quietly, “The Palestinians are thirsty for a state. They want an identity, a passport. But I don’t think there would be a public declaration of recognition-or non-belligerency if the state were established. It would be a de facto situation.”

But Kaddumi doubts whether the Arabs would be satisfied if an Israeli withdrawal were forced by the great powers. “It has to be a courageous move by Israel,” he says. “Without that there will be war. Israel should ask the Palestinians what they want, should say they are willing to discuss everything, even a democratic state. Then let them argue it is impractical. But they can’t start by saying “we will not give up this and this’.”

Many Palestinians here insist that the PLO cannot spell out what it will give up for a state until the Israelis make a concrete offer. “The Israelis know they could get a state,” a Palestinian professor told me impatiently. “Arafat is saying it, people are saying it. But the Israelis have to declare they will go back (from the occupied territories) yet every day they say they want to stay in Sharm el Sheikh and here and there. Their basic policy is always to give the Arabs an offer, which is not acceptable. If the Israelis would declare they would go back to the 1967 borders there would be peace in two weeks.”

“Maybe Arafat would agree to non-belligerency,” he went on, as we looked out over the Persian Gulf towards Saudi Arabia, “But we have only a very few cards, and if we lay our cards on the table before they offer anything what do we have?”

Many middle class Palestinians here echo civil engineer Ibrahim Salah, who told me as we sat in his comfortable four room flat in Salmiyeh, “We should take anything we can get. We need a place so we can establish ourselves.” Mr. Salah arrived in Kuwait ten years ago from Jerusalem. His wife, Fathyia, is a teacher, who is frustrated at how much less she earns than her Kuwaiti colleagues. “Would we accept non-belligerency?” Salah asks rhetorically. “Maybe there will be no war for ten years, but they cannot tell us whether or not to fight. If there is a state Israel will change. They will have to recognize the Palestinian people.”

Fathyia, a round, vivacious woman who is laying out chicken and stuffed grape leaves on the table, joins in. “If the West Bank is a first step we will take it, but without recognition of Israel. Maybe it will take time, we are willing to wait, but a new generation of Israelis will accept the democratic state.

“I took my children to Palestine, I showed them Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock. It isn’t like it was before- they are changing it. I cried, it was so beautiful going back to visit. But how could I explain why we weren’t allowed to stay? Here the heat is killing us and in the winter the desert is terribly cold. Life here is purely practical; you are here to earn money and nothing more. Nobody plans to stay here forever.”

But while they may not plan to stay, would they go back if a West Bank state were created? If there were any prospects of work at all, probably the first to return would be the thousands of poor Palestinians in Kuwait, who do not receive enough economic benefits to make them hesitate. Or, many of them might return to their pre-1967 arrangements, sending their families back to the West Bank and remitting their paychecks.

For the middle class there are many question marks. Many people admitted to me, some openly, some after hedging, that they were too well established in Kuwait to leave. But they would be eager to take Palestinian citizenship, giving them a new status here, and most would be frequent visitors, perhaps building homes there. The key factor would be freedom to go and come as they pleased. For others, the decision would turn on whether they came originally from the West Bank. (Rather than inside the pre-1967 boundaries of Israel), and on the political climate and economic prospects of the new state.

“What kind of a state — a puppet or a real independent country,” asks one middle level Palestinian bureaucrat in the Information Ministry. “And what kind of jobs? I would go back, but I would make arrangements so that if I could not do something of value there I would come back here. It is not a question of pay; half pay there is enough. But I would accept citizenship immediately.”

| Prof. Rabieh and family |

Despite their political reservations about a West Bank state, many Palestinians here become enthusiastic when talking about its economic prospects. Kuwait contains a rich reservoir of potential administrators and developers for a new state — if they went back. For men like AbdelMohsein Cattan the challenge is heady: to use their wealth of experience to build for their own state structures such as they set up in Kuwait. Already there is talk here of holding a conference of Palestinian businessmen to discuss development prospects for a future Palestinian state.

“I would go back,” says Cattan, “But Palestine couldn’t absorb all its people back. We need to make it easier for them to go outside. With a state it would help the Palestinian outside to feel secure, it would give him protection.”

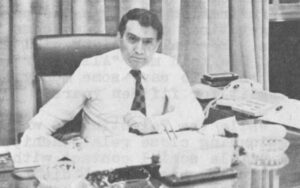

The new state might become an exporter of trained personnel to Kuwait and the Arab Gulf according to one highly respected Palestinian economist at Kuwait University. Prof. Mohammed Rabieh, who grew up in a refugee camp in Jericho after his family lost their home in Jaffa in 1948, and received a Ph.D. from the University of Houston, feels the Palestinian state would help solve the acute shortage of skilled manpower opening up all over the Arab Gulf. “The West Bank couldn’t absorb all the Palestinians. Those who own land would go back, but the state would have to establish the most advanced educational and medical and consulting centers and export its manpower. It could also develop service industries and tourism and electronics industries.” The crucial difference between this scenario and the present? — if a Palestinian abroad felt fed up, he could always go home. But Prof. Rabieh also feels it will take another war to create the possibilities for a settlement.

And if there is no settlement, will the Palestinians of Kuwait forget their dreams? The answer, I was told over and over again, was that “our children are more nationalistic than we are. They have grown up knowing that they are something different called Palestinians and they can’t forget it.” What they will do about it remains to be seen.

Kuwait, June 1975.

Received in New York on August 8, 1975

©1975 Trudy Rubin

Trudy Rubin is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Rubin, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.