The Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon present a special obstacle to a peace settlement in Geneva; Most of the 95,000 refugees in 15 camps in Lebanon come originally from the northern Galilee or from the areas around Jaffa or Acre on the Mediterranean coast. They do not consider the West Bank of Jordan their home — many had never even visited it before they fled in 1948 — and thus feel they have little to gain from a West Bank-Gaza Palestinian state.

I visited three Lebanese camps (I plan to revisit and write more extensively about them in the future). In Shatila camp on the outskirts of Beirut, I was accompanied by a representative of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the families with whom I spoke were supporters of that group. In Ein el-Helweh and Mieh-Mieh camps outside Sidon in the south, I visited on my own in the company of camp residents.

Over and over I was given the same message: to these people, going to the West Bank meant only going into a new exile. What would they do there they asked me? Where would they live? Older people talked to me of their villages in Israel as if they had never left.

Many people told me they would not want to leave the camps even if a settlement were concluded unless they could go back inside Israel proper. (But only a few said they would go back if the state was still ruled exclusively by the Israelis.)

The feelings of these refugees are important for another reason. Since the Jordanian government decisively defeated the Palestinian commandos in 1970-1 and drove them out of their bases on Jordan’s east bank, the Lebanese camps have become the chief stronghold and source of recruitment for the guerilla movement. (The guerillas took over administration of the camps from the Lebanese government in 1969.) This remains true despite the tension between the commandos and the government in Lebanon, which resulted in bloody clashes between the two in May 1973 and a subsequent uneasy truce-under, which the Palestinians agreed not to attack Israel from the South, incurring Israeli reprisals on Lebanese villages. The Lebanese government would be only too happy to see a Geneva settlement, which enabled them to get rid of the Palestinian camps in their territory. Observers in Beirut expect that large-scale fighting might erupt between the camps and the Lebanese in the event of a settlement.

Of course, any peace settlement accepted by the Palestinians would have to deal specifically with the problem of the refugees in Lebanon. It is a delicate area which would have to be handled with much skill: how to move, house, integrate and find jobs for those refugees who wished to move; what provision for those who wished to stay; what compensation for those who lost property inside Israel; what possibility for them to return to their birthplaces. One UNRWA official commented to me, “There wouldn’t be any problem with funds for resettlement on the West Bank. So many people would like to have this thing solved that the money would flow.” Some Lebanese suggested that the refugees might be encouraged to go to Syria, which needs manpower for agricultural development.

But money cannot solve the psychological problems. Settling on the West Bank means once again becoming a refugee to many people in the camps. They would probably prefer to keep the little security they have rather than start over again. However, most refugees with whom I spoke expected that the Lebanese government would try to make life miserable for them, even should the agreement provide that they could stay. “The government would probably like to march them right to the border,” one Lebanese journalist told me. “What’s more likely is that it will make it impossible for them to get even the meager work they find now. In addition, of course, the government would re-exert control over the camps. After a settlement the commandos would never be permitted to keep the private enclaves they have now. Then the refugees would be right back to the intolerable conditions they had before the resistance came in four years ago.”

I visited the camps to discuss these problems. The brief portraits below of people I met suggest themes I heard repeatedly. When I was inside homes the hospitality was generous and relaxed, but commando officials in the camps were nervous about outside visitors and I was unable to take photographs of the camps (hence the lack thereof in this newsletter).

The camps in Lebanon vary in appearance from shantytowns to small villages to a mixture of both. The ones in the Beirut area appear the worst. Crowded onto smaller pieces of land than those in rural areas, they are made worse by the addition of squatters who build along the camps’ edges. (UNRWA at one point tried to buy private property to relocate the Beirut camps but could obtain nothing close to the city.)

Much of Shatila camp (pop. 4200) consists of tin and wood shacks with tin roofs held down by large stones. Most of the narrow alleys between houses are still unpaved although the larger through roads in the camp have paving and recessed drainage ditches running alongside. The camp has electricity and most homes have a line running along their ceiling with one or two bare bulbs.

Many of the camp dwellers find manual work in Beirut. Their small incomes are reflected in the modest furniture, which can be found in many of the one, or two room dwellings, often those which have been rebuilt in concrete. Most common is one double bed, augmented by blankets and bed pads rolled up by day and spread out on the floor at night. Those who are fortunate to have found or expropriated extra land (often a factor of luck when they first arrived) have their one or two rooms hidden behind a fenced off courtyard, often sharing the area with rooms belonging to relatives.

The commando groups have brought visible changes to the camps and even those refugees who are not politically involved talk of them. In Shatila, one family explained that their concrete one-room shelter with concrete roof had been built only two years ago. Prior to that they lived in one of the tin-roofed shacks still clustered all over the camp, “In order to add one nail to your house you had to have the permission of the Lebanese authorities and you could never get it,” complained the owner of the house. Pulling me outside into his courtyard he pointed to two thin pipes running along the edge of the paved path between the two rows of houses, “These pipes are also only two years old,” he told me. “Before that there was only one water tank for the camp. You had to wait for hours in line each morning. Now there are many taps and some houses have their own.”

The Old Man, Mohammed

Ein el-Helweh (“the sweet spring”) is the largest of the Lebanese camps. With 20,000 registered refugees it matches the population of the ancient Phoenician port city of Sidon beside which it sits. The camp has the appearance of a large village, with several wide paved roads crossing it, and whole sections of small shops open on one side selling fruits, groceries, clothing, and household items. Many of its dwellings are hidden behind gate doors and tiny fenced off courtyards with tin cans along the fence tops sprouting flowers and bushes and giving the streets a touch of humanity.

| Ein el-Helweh camp, in front of Sidon and the Mediterranean UNRWA photo |

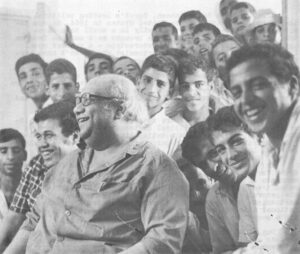

I was standing inside the headquarters of the Democratic Popular Front, a plain, shabby, unfurnished room, fronting a small grassy courtyard in which a dozen ten and eleven year olds, “Ashbal” or commando cubs, were being trained to dismantle a Klashnikov rifle by a blonde Palestinian youth in Wrangler jeans and jeans jacket.

Intent on the eager efforts of the children, and the paradoxical appearance of their instructor, I did not notice an old man approach in a shabby grey jelaba (with a label “Made in England” on the chest). His kaffiyeh hung down over red-veined cheeks and a thin grey stubble. Squinting at me with watery blue eyes, he invited me and my friends from a neighboring camp for coffee at his home.

It was a poor home, two adjoining rooms opening directly onto the road with no courtyard, I caught a glimpse of several women in the rear room. I was invited into the front room, cement with a tin roof, and seated on one of two matching green couches with gold fringe. Green and gold striped curtains and valances hung from the shuttered windows. A double bed covered by a bright red blanket stood in the corner under a photo of Gamal Abdel Nasser and a map of pre-1948 Palestine. The two rooms were shared with the old man’s only son, daughter-in-law, and eight grandchildren.

Two elderly women appeared from the rear room, wearing print cotton, ankle-length dresses, and kerchiefs over their hair. One brought me a towel to cover my exposed legs. “I am from the old school and it offends me,” the old man told my young interpreter.

The old man was eager in his praise of the resistance, “Before they came the Lebanese made our lives difficult,” he told me. They wouldn’t let me build this cement room. My son did it two years ago. And they have pressed UNRWA to cover the roads and improve the health situation.”

The old man, who sits by day in small shop selling vegetables to augment his son’s income as a laborer, insisted he “would never accept” a West Bank state. “I want to go back to my village (near Haifa). I won’t go back if Israel rules. I would like to go back without the existence of Israel, even if it is to live in a cave.”

He, like many older refugees I met, made a sharp distinction between what he called “Jews before 1948” and those who came after. “Before 1948 there were Palestinian Jews,” he told me, “but when the Zionists came they began to discriminate against Arabs.” But he told me a story to prove, he said, that “Arabs could live with Jews.” “After we fled from our village in 1948, I snuck back because I had hidden money in the house and we had no money in Lebanon, I stayed three days. There were Jews living in the house, but I got the money from the hiding place. A Jew who was in charge of the area knew I was there but he refused to arrest me or kill me. This means we can live with the Jews if there is understanding.”

Abu Rahmeh, The Teacher

Abu Rahmeh is an angry man who shows his bitterness. He is a teacher in an UNRWA training school near Sidon; UNRWA teachers are nearly all Palestinians and are often the best paid workers living in the camps. Those in camps often move outside to better quarters. But Abu Rahmeh decided to bring the better quarters to Ein-el-Helweh,

Two years agog after the arrival of the commandos had made new construction possible, he built a two-story apartment dwelling with four units just inside the camp boundaries, with money he had saved from six years’ work in the Gulf and Saudi Arabia, and moved his whole extended family into it. He says he never could have afforded to move his whole family out of the camp, and besides, he wants his two-year-old son to grow up in the camp.

Abu Rahmeh is a politicized man; he would not admit to membership in a commando group, but he strongly opposed a West Bank entity in favor of the PLO’s theoretical goals a democratic, secular state in all of Palestine.

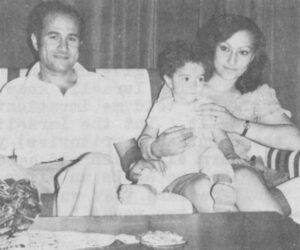

We sat in his neat two-room apartment on Danish modern furniture. A TV sat atop a full bookcase and behind it a white crib with mosquito netting drawn over it cradled his two-month-old daughter. Rahmeh, the chubby two year old pranced around, singing a commando song at the request of his father. I only recognized the last words; “grow up to be a fedayi”. But I learned that he also sang of playing basketball with Moshe Dayan’s head.

Abu Rahmeh’s wife, slim and attractive in a stylish pantsuit, served us with tea, hummus, bread, fried potatoes, salad, and meat with lentils, as he spoke of his past.

“We left Palestine in 1948 after our town had been occupied for three days. We came by foot. Father had some money but the Jews took it at the border. We had nothing. When I was a small boy I was cold. I said to my father ‘help me’ and he put his clothes on my back.

“I graduated from the UNRWA training school at Siblin as a mechanic. I went by myself to Kuwait to work when I was 16 after writing to many companies seeking jobs. Later I went to work in Saudi Arabia. In 1971 I tried to collect money for the commandos from fellow workers and I was arrested, I spend seven months in a Saudi prison.” He pulls up his left pants cuff to show a sear around his ankle. “This is from the leg irons.”

Two of Abu Rahmeh’s sisters share the house. One is a widow; her husband joined the commandos and was killed one year ago. A third sister died in the camp twenty years ago because of inadequate medical care. A brother, blinded in the 1948 fighting, also lives in the house.

Abu Rahmeh gets angry when the conversation shifts to Geneva, “What about the Palestinians from 1948? What about me? The West Bank and Gaza is not enough for all our people to live. It would be a grave for our people. Suppose we take the West Bank and Gaza and after two or three years our people start again as commandos to try to regain our land completely. Most of the countries in the world will say we are doing a bad thing.

“I can’t say the PLO are traitors (for speaking of the state) but they are wrong. I don’t want to push the Jews into the sea. I want a democratic secular state — Christians, Moslems and Israelis. We are ready to live together but we don’t think the Jews or Israel will approve of this case.

I have built a house here but the land is not mine. The Lebanese may want it back some day. I want the sand in my country, it is enough. The air….

“If some rubbish commander accepts Geneva…. Well, never mind, the resistance will start again. And things will change, Egypt will change. Now Sadat tries to change what Nasser did but he will end like King Farouk.

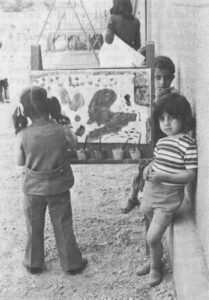

| Children at Shatila camp |

| |

|

“Maybe I won’t live to go back. But I have to teach my son about his country. I don’t want my son to say someday I was a traitor. If I don’t liberate one centimeter of our land, maybe someday my son will do it….”

Yasmin, A Young Mother

Yasmin’s sturdy brown foot tapped on the concrete floor as she cradled the youngest of her nine children and talked about leaving Palestine when she was seven years old.

| Yasmin and her daughters |

She sat on a yellow and navy striped couch under a framed collection of family photos with a snapshot of PFLP leader George Habbash tucked into the corner. On the opposite wall a large colored photo of Gamal Abdel Nasser stared down at the group. We sat in a circle against the turquoise walls, Yasmin’s four year old daughter perched on the white coverlet of the double bed in the corner, leaning on a hand embroidered pillow, and her elderly mother huddled on a small chair hidden under a long white shawl. Two male neighbors leaned on a table covered with schoolbooks. Small children drifted casually in and out.

The room was prosperous by camp standards, a concrete roof, a refrigerator in one corner, an electric cord tacked across the ceiling from which a lone bulb dangled, and a radio on the table. This room opened onto a small courtyard shared by three less prosperous dwellings: the small tin and wood hut of Yasmin’s mother shared by three of the young woman’s children, and two neighbors’ tin-roofed shelters.

Unlike my visits to En el-Helweh and Mieh Mieh camps, I was accompanied here to Shatila by a representative of the PFLP, a young blind man named Mahmoud, who assiduously translated directly every word of Yasmin and her guests, sometimes pausing to tell me with concern, “You know this is not the PFLP’s official position.” (Before reaching Yasmin’s house, we had to stop at PFLP headquarters in the camp, a grimy second floor room where my officially stamped pass was checked by several young men with Klashnikovs.)

“I am from Yashour (sic) village near Haifa,” Yasmin recounted, “and I still have some relatives in Palestine, but they have left their original village and are refugees all over the occupied land. Our village was completely destroyed and even its land ploughed under.

“I remember that the Jews who were in Palestine never hurt us and tried to tell us we must stay there and we will fight together against the mercenaries who came from outside. The Zionists just came to kill.” (Although Yasmin would have been quite young to remember such things, this theme of the pre1948 Jews being friends and the post-1948 arrivals being enemies was one that I heard repeated several times in the camps.)

Her family had been farmers and shepherds. They fled, she explained in a loud emotional voice, not only because “the Zionists were starting to attack around their village”, but also to protect the honor of their women, “After we left, we used to move from village to village, going north.

“It was very difficult to find a place to stay. We were scattered in the mountains without food and clothes. Before we reached Lebanon I remember we arrived at a tree and my mother took off her dress to cover the small children. When we reached Ermaish (sic) village the people there were tired of receiving refugees and nobody would give us water. My father put me down a well with a rope at my waist and I had to take muddy water because we could not afford fresh.”

“We were obliged to beg for food. We were not used to it and were shy to ask for it. We just laughed when we remembered how we were and what we had become.”

Finally “the Red Cross collected us in cars” and they were transferred to old French army barracks at Baalbeck, Lebanon. They lived ten families in one room, and as the months passed the parents still told the small children hopefully that they would be going home “in a week.” Five years later they moved to Shatila camp near Beirut because it was impossible for the men to find any work in the rural area around Baalbeck.

“When we arrived here we were living in tents. In the winter they filled with water. My father in Palestine had had his own work and had hired workers. But when we arrived he worked taking care of horses. All the children had to leave school and work because he made only about 35 Lebanese pounds (now equal to about 15 dollars) per month.”

Her neighbor, a handsome stocky young man with short curly hair and mustache interrupted with a wave of his hand and another complaint which I heard frequently in the camps: “When we used to go to work outside we were treated as third class. At a time when the Lebanese worker got four Lebanese pounds we got 1 1/2 because they knew our need. Even now I make half of what a Lebanese worker gets (working as a typesetter for a Beirut newspaper.)”

As the anger level in the room rose, the old lady suddenly jumped up with a shriek and grabbed my hand, dragging me w1th surprising strength out the door. “Look at how our people live!” she shrilled, tapping on her zinc roof, pulling at the plastic sheets which hung down over the spaces between the zinc and the concrete walls, touching the cracks in the concrete, pointing at the stones which sat on the roof barely pinning it down in high winds.

| Kindergarten at Shatila camp. |

“Would you accept this life?” she demanded, clutching my hand.

Her daughter, following behind, led me back into her home. “We are now in much better condition than before the resistance came (in October, 1969),” she told me, relating details similar to those I had heard in Ein el-Helweh. “The concrete building is only three years old. When they came they began to improve conditions. Before then if something was wrong we couldn’t fix it without government permission.”

Crossing her legs under her long brown skirt, she added, “Before they came we felt we were in prison. Only some of the camp had electricity. There was only one water reservoir for the whole camp and you had to wait for hours. Now every house has electricity and a tap.

“Before the Fedayeen came I only stayed in the house with my nine children. After they came I began to raise funds, to speak of politics and understand.”

Although everyone in this room was a PFLP supporter (the PFLP is the principal resistance group opposing a West Bank state), the words, which they used to reject the state idea, were the same I had heard from camp dwellers who were not formally connected with any group.

“We completely refuse a state on the West Bank and Gaza,” Yasmin shouted in harsh guttural tones. “It would not be useful for us. We want to go back to the territories occupied in 1948. If we all die we will accept nothing less than to go back to our country.

“We wish wholeheartedly to live with the Jews who lived in Palestine. But the mercenaries would have to go back, those who came from abroad, those who fought us and occupied our houses.”

Did this include all Jews who came after 1948, I asked.

A firm “Yes!”

And their children, who had been born in Israel?

“Yes!”

The PFLP man squirmed and whispered to me that the official position was that all non-Zionist Jews could remain.

“I train my children to understand this, even the small baby,” Yasmin continued, looking down at the sickly infant. “If the Palestine state is created in spite of us, we will continue fighting. No solution can be made without our will.

If the West Bank people go back, what about us? Even if we were given land we would feel it was not our motherland. I will not leave the camp until I can move directly to Palestine.”

Looking down at her child she murmered under her breath, “If the Palestinians in 1948 were enlightened as the new generation are now, even if all were killed, Palestine would not have been lost.”

Received in New York May 20, 1974

©1974 Trudy Rubin

Trudy Rubin is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Rubin, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.