London, England July 28, 1973

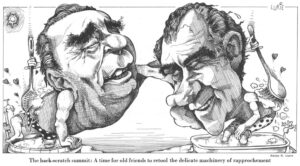

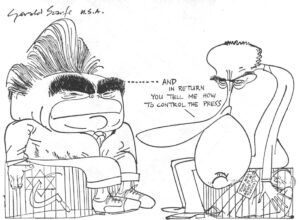

Henry Kissinger’s appeal for a bipartisan Watergate cease-fire on foreign policy issues to permit his work for a “lasting peace” to continue abroad, while the United States sorts itself out politically at home, strikes a chord in West Europe. On balance, despite many reservations, America’s allies rate the Nixon foreign policy and Mr. Kissinger favorably. Without forgetting the scars left by some of Washington’s hard-nosed methods in recent years — “We got the Watergate treatment too,” a high Common Market official commented — West European leaders are less concerned than Americans about the White House “horrors” and more horrified over the possibility of 3 1/2 years of Presidential paralysis overseas. They hope for Mr. Kissinger’s success in the efforts he reportedly has been making, with Mr. Nixon’s approval, to unite Democratic Senators and liberal Republican leaders, including his old patron, Nelson Rockefeller, on the next steps to consolidate détente with Russia and China and to revitalize the Atlantic partnership with West Europe. A return to the kind of consultation at home required by a bipartisan foreign policy — which would restrict Nixonian secrecy, surprise and overnight reversals of position — might even permit more consultation with the allies abroad!

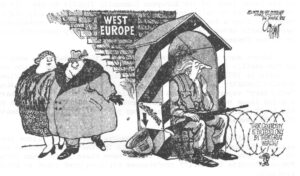

West Europeans are concerned about the fate of the Administration’s trade legislation, its position on monetary reform and such new agricultural policies as export embargoes, but officials here worry even more about the outcome of Senator Mansfield’s new drive, over Administration opposition, unilaterally to withdraw half the American troops in Europe.

In the past, Mr. Mansfield has insisted that the troops withdrawn from Europe could be maintained in readiness in the United States for rapid airborne return in an emergency and would not reduce the American force commitment to NATO. But now, Europeans note, he argues that the withdrawal of these troops “would reflect the judgment that they were not needed to fulfill existing international and domestic obligations and therefore appropriate for demobilization.” Senator Mansfield’s new view is that major defense cuts are justified by developments lessening tension between East and West as indicated in a list he has assembled of 82 such events since 1963.

“They range” he said, “from the hot line to the nuclear test ban to the consular convention to the nonproliferation treaty to the treaty normalizing relations between Germany and Poland; to the German treaties with the Soviet Union; to the SALT treaty; to the signing of the treaty on relations between East and West Germany….

“It is time that the U.S. recognized the existence of its own policy toward the East. The policy of this government should be consistent, not one of engagement with the Soviet Union in trade and cultural exchange and confrontation in military matters.”

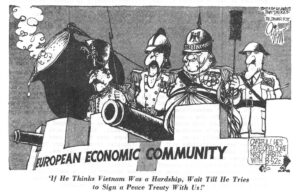

West Europeans, with Senator Mansfield, would like to believe Leonid Brezhnev’s assurances that the Cold War is over but, for the moment, they feel that NATO must keep its powder dry. An armistice has been signed, but a peace treaty is not yet in sight. Meanwhile, Russia’s allegedly peaceful intentions have not led to any reduction in military capability in Central Europe. On the contrary, Soviet forces have been strengthened. West Europeans, as a result, see no justification for unilateral withdrawals of American troops — and are reluctant even to see them trimmed back in return for Soviet cuts in the impending mutual force reduction (MBFR) talks, which will open October 30 in Vienna. Unilateral American troop withdrawals, as urged by Senator Mansfield, seem to West Europeans likely to encourage a return to adventurism in the Kremlin, if not by the present leaders, perhaps by their successors.

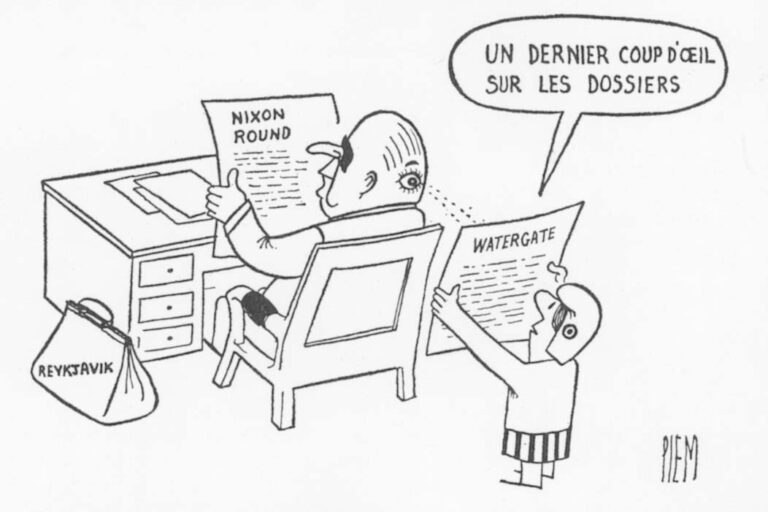

German officials contrast the alacrity with which American Senators talk of unilaterally slashing U.S. forces with the caution evidenced by Mr. Brezhnev in discussing Soviet cutbacks, even in a far-less-risky mutual force reduction agreement. During his recent visit to Bonn, the Soviet Communist party secretary showed his growing mastery of foreign policy issues by discussing most matters extemporaneously. Only three years ago, he always carried a bulky briefing book, from which he often read the Soviet position. Even as recently as a year ago, Mr. Brezhnev usually spoke from notes in negotiations with Western leaders. This year notes were never in evidence — except once, when mutual force reductions were discussed. At that point, Mr. Brezhnev spoke cautiously from a detailed memorandum. He made it clear that Moscow wanted to move slowly, step-by-step, and had a purely nominal force reduction in mind, perhaps as little as five percent as a starter.

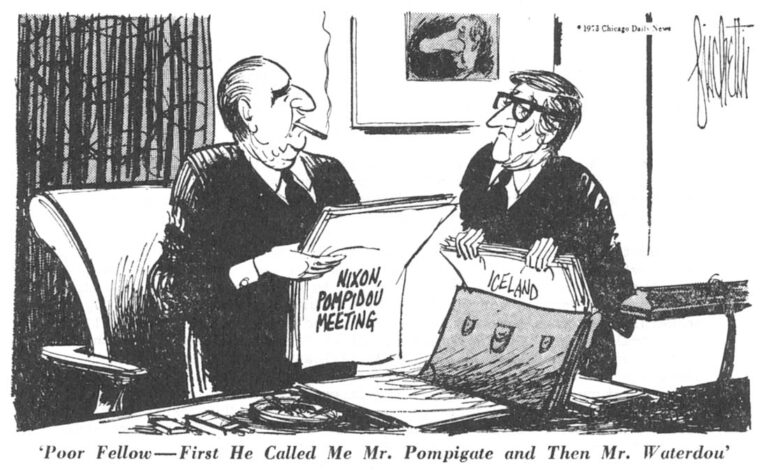

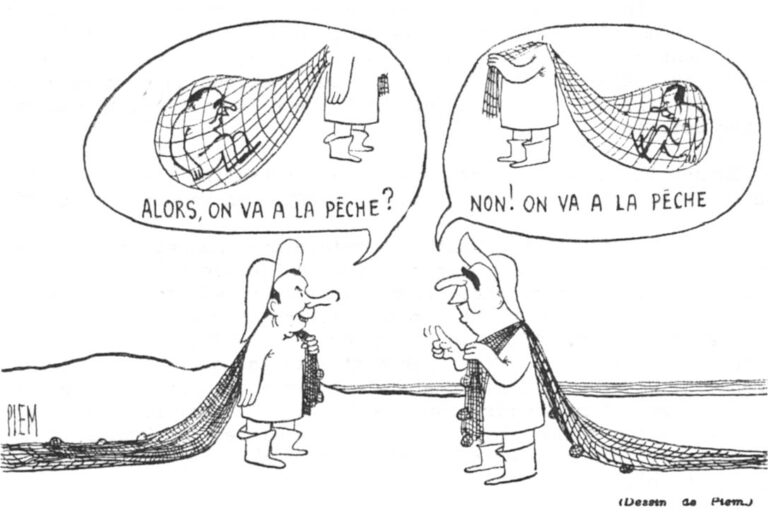

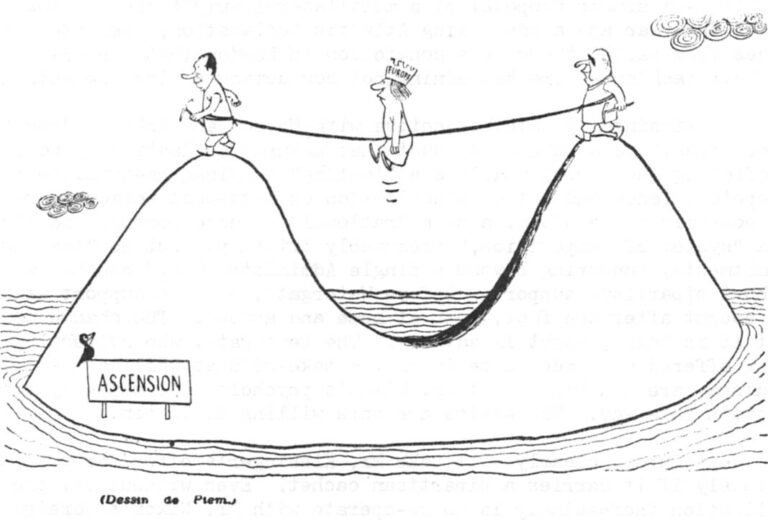

The NATO allies believe Mr. Brezhnev’s caution should be emulated in the West. The French government, for one, is as much opposed to negotiating for mutual NATO-Warsaw Pact force reductions — which the Nixon Administration is pressing, in part to contain the Mansfield Resolution — as it is to unilateral Western cuts and has refused to take part in the Vienna MBFR negotiations. President Pompidou went out of his way during his meeting with Mr. Nixon in Iceland to announce publicly his view that American troops are vital for Europe’s defense, a crucial first step toward revising the defense position of General de Gaulle, who sought French “independence” by expelling American troops from France, withdrawing from NATO’s defense planning and integrated commands and pretending that it was of no concern to France whether or not American troops remained elsewhere in West Europe.

Fortunately, de Gaulle did not denounce the North Atlantic Treaty. France, as a result, remains in the Alliance. But, despite Mr. Pompidou’s Iceland statement, the commitment of Gaullist politicians to the General’s myth of “independence” makes it politically difficult for the French President to return to NATO’s system of military integration — far more difficult than it was for him to reverse de Gaulle’s veto of British entry into the Common Market.

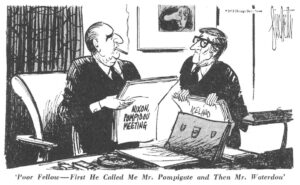

When Mr. Nixon in Iceland commented that he had always admired General de Gaulle and became more Gaullist every day, Mr. Pompidou quipped, “And me, less and less, it’s said in France!” It is in this context that observers here and in Paris interpret the interesting remarks on defense made after Iceland by France’s Kissinger, Michel Jobert, in his first major statement of policy to the National Assembly after his appointment by President Pompidou as Foreign Minister.

Europeans commenting on the American proposals for a “Year of Europe” even when sharply critical of Washington, have tended to echo the Nixon-Kissinger thesis that major economic conflicts between the United States and West Europe threaten the Atlantic Alliance and must be resolved. Mr. Jobert discussed the trade and monetary issues but put his emphasis elsewhere.

“I do not know whether the year 1973 will be the “year of Europe,” he said, “but I am sure that in 1973 the question of the defense of Europe will be hovering in the background of all the talks which will be taking place in Europe and elsewhere and perhaps it will even come to the fore.

“In effect, when the United States proposes to enter into a dialogue with members of the Atlantic Alliance and more especially the nine partners in the European Economic Community about the goals, the ultimate purpose of the alliance, the conditions for reshaping it, or the conditions needed for a new organization, whatever the factors weighing in the balance, it is primarily the defense factors which are and will be decisive.”

“While the United States questions the cost of its presence in Europe, I refer to its military presence, while it asks its partners to assume a more equitable share of the burden of which it claims to shoulder the heaviest part, while it hopes that the advantages it concedes here can be compensated elsewhere — I am referring to trade — European countries are quite aware that the real debate and the real question concerns Europe’s security.”

All this is quite clear, as are Mr. Jobert’s expressions of concern over the direction of Soviet-American negotiations on strategic arms, force reductions in Europe and other matters, including “the temptation of the superpowers to regulate, by means of their dialogue, the parceling out of world responsibilities.”

What is enigmatic is what Mr. Jobert proposes to do about the security problem posed for West Europe by the United States which, as he sees it, has opened wide-ranging negotiations with the enemy, while confronting the allies with stiff demands for trade and monetary concessions in return for continuing a reduced defence contribution.

“The European Community has to assert itself a little more each day,” he said. “This Europe, the Europe of the Nine, is basically unarmed. Of course there are national armies equipped with conventional weapons; there is also France’s nuclear force, which is free from all liens; there is the British nuclear force supported within the NATO group by American means. Nevertheless, with the exception of France, Europe now has no autonomy in terms of defense and it is paying for this…European defense is beginning to look more and more as if it should have its own character.”

All this suggests that France at last is prepared to consider some move away from General de Gaulle’s thesis that “there is no defense except national defense” and toward some defense projection of the European Community. But what? An Anglo-French nuclear force? A true European Defence Community? Or some easier first step, congenial to the military-industrial complex, such as a European defense procurement agency to shift increasingly from American and national European arms to weapons developed and produced cooperatively by transnational European consortia? No indication of what the French government has in mind has been forthcoming though there are rumors that a Pompidou proposal will be made in the fall.

But nothing done in this field can, for a decade or more, alter the present fundamentals. Meanwhile — and, perhaps, most important for the negotiations of the Year of Europe — Mr. Jobert acknowledged that “Western European countries cannot without American help achieve that balance of military power without which there is no security nor even lasting détente.”

Does this suggest a first step toward preparing French opinion for greater French defense cooperation with NATO, as Washington urges?

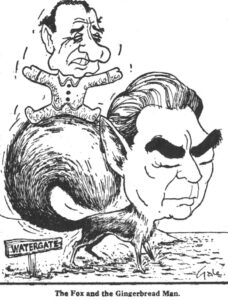

Prime Minister Edward Heath of Britain and Chancellor Willy Brandt of West Germany reportedly have both warned President Pompidou that isolationist and protectionist forces in the United States could get out of hand without help from the European allies in resolving not only trade and monetary issues, which are beginning to move favorably, but some defense issues as well. With President Nixon’s political authority weakened by Watergate, the danger is even greater. And some London officials see a further risk that the President himself, if hard pressed, will play to the gallery by “clobbering the allies and knuckling down to the Russians,” since détente is popular in the United States and the allies are not.

For the moment, Henry Kissinger’s effort to achieve a bipartisan consensus in Washington on the Administration’s next foreign policy moves is paralleled by discussions among the nine European Community countries. They are trying to agree by September on the response to the Nixon-Kissinger proposal of a multilateral Summit meeting toward the end of the year and a resounding Atlantic Declaration. Despite negative noises from Paris, there is a conviction in London that the French — in their fashion — are bargaining, not conducting a blocking action.

Mr. Kissinger’s chief objective with Moscow and Peking, “our former adversaries,” is a code of conduct that assures a “lasting” peace. He is offering the European allies a “lasting” American recommitment to Europe’s defense and better consultation on East-West policy in return for economic concessions, a more “rational” defense posture and agreement on a “system of competition,” presumably friendly. But no “lasting” commitments, “enduring beyond a single Administration,” can be made without bipartisan support. Before Watergate, outside support usually was sought after the fact, both at home and abroad. The change now is that it is being sought in advance. The Democrats, who evidently are being offered a chance to be in on the take-offs as well as the crash landings, are doubtful about Mr. Nixon’s psychological capacity to function this way. The Allies are more willing to listen.

West Europe clearly will take Mr. Kissinger’s offer far more seriously if it carries a bipartisan cachet. Even without it, the inclination increasingly is to cooperate with Mr. Nixon’s foreign policy proposals to the extent that this can be done without sacrificing important interests. The question, in the view of a high British official, is no longer whether an Atlantic Summit will be held but whether a declaration can be drafted for it to issue. If an Atlantic declaration can be agreed in the fall, a Summit should not prove too difficult to arrange. What is far from certain is that a common statement of Atlantic goals and tactics in East-West as well as West-East policy can be easily achieved.

(To Be Continued)

Received in New York on August 8, 1973.

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, the Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.