London, England September 19, 1973

West “We’ve achieved strategic parity. But we haven’t achieved economic parity.”

This comment by a leading Soviet professor during my visit to Moscow indicates the skepticism among Russian intellectuals about the regime’s management of the ailing Soviet economy. To all the perennial troubles that have harassed the world’s first Communist economy for decades, a new and more ominous worry has been added: Russia’s industrial growth rate has been slowing down.

No more is heard of Khrushchev’s boasts that the USSR would overtake the American economy and defeat Western capitalism by the power of example in providing a better life. The increase in the industrial labor force, which has helped account for the extraordinary rise in output since World War II, is flattening out along with population growth. Productivity gains, which require heavy capital investment in new technology, must be relied upon as the chief source of growth in the gross national product — one reason why capital as well as technology is being sought from the West.

Thirty percent of the work force is still engaged in agriculture, compared with 12 percent in the Common Market and less than five percent in the U.S., but further reductions are likely to be slow. Agriculture is in worse shape than industry. Climate, soil and the collective farming system have combined to confront the Soviet leadership with recurrent food import needs, despite efforts to maintain self-sufficiency. Without the huge purchases of American grain in 1972, there could well have been food riots in Soviet cities that, some analysts believe, might have shaken the Soviet power structure.

Despite steel production of more than 130 million tons a year, the Soviet economic system has been unable to meet the country’s hunger for consumer goods, not to mention the easier life and economy of abundance three generations have been promised and denied.

Mr. Brezhnev alluded to the problem during his June visit to the United States, when he told American businessmen that men can wear the same suit all day, but Soviet women, like women everywhere, want to change dresses three times a day. The shoddiness and incredibly high prices of Soviet clothing and other consumer goods in terms of average incomes shock the Western visitor even to the best-stocked Moscow department stores. The selection is much poorer elsewhere in the country.

Drab poverty is the impression Soviet life still gives first-time Western visitors 56 years after the Russian Revolution. One who has made successive visits to the USSR over a quarter-century notes gradual improvements — the large amount of new housing, for example. Huge new apartment blocks, though unattractive, have virtually eliminated the one-family-per-room crowding of the past. But, even so, the impression grows that the more things change the more they are the same.

The Moscow atmosphere remains oppressive. The economy produces more but still fails to satisfy human desires. Whatever it is that consumers want most at any time is certain to be in short supply or impossible to obtain. Style, elegance, beauty, color are lacking not only in everyday life, but are unavailable even for special occasions. It is a dreary, Puritan, work-oriented world, lacking in cheer, gaiety, hope and even the concept that people have a right to enjoy life, not to mention the “quality of life,” on which so much discussion now focuses in the West. Wholly apart from the larger questions of injustice, illegal action by police and courts, privileged elites, other inequalities and the absence of freedom — political, trade union, intellectual or artistic — the Soviet system, in its own terms, is a disappointing performer. The heavy and inhuman weight of bureaucracy, red tape and regimentation -combined with all the dodges human ingenuity can devise to get essential things done within this work-to-rule structure assures minimum efficiency. An economy of acute scarcity persists at a time when the capitalist democracies have achieved breakthroughs toward the economy of abundance that Communism was supposed to provide.

In space, in missiles, in other armaments, the high quality of Soviet products is acknowledged. But the visitor to Moscow in 1973 is struck by the slow pace of Soviet planners in facing up to the problem their rigid, centralized production-oriented economy confronts in going beyond standardized necessities — and such regime-favored products as television and radio sets, useful for transmitting propaganda to the variety of goods and services needed to meet the “revolution of rising expectations” that has overtaken the Soviet consumer.

Italy’s FIAT automobile company has been brought in to make Russia’s first mass-produced automobile, which can now be seen on the streets. But the upper income Russian, who saves up a year’s salary or two to acquire a car after two or three years on a waiting list, will face more problems than it is worth — until the government gets around to providing gas stations, spare parts, repair garages, covered parking for the winter blizzards and a network of paved roads. There is little sign of any of this yet.

Moscow’s three or four so-called “luxury” restaurants are packed nightly with Russians who have reserved weeks ahead for the privilege of splurging a week’s pay to celebrate an anniversary or birthday. But the quality of food compares unfavorably with a Howard Johnson short-order counter and it can take three hours to be served a barely-edible meal. The menu is elaborate. But few items on it are available.

“We call this Soviet democracy,” commented a waiter in one restaurant. “You eat what I like.”

Luxury foods like caviar, a gob of which was on every worker’s monthly ration card, is on sale mainly to foreigners for foreign currency at eight times the price of a few years ago. Pollution in the Caspian Sea has contributed to the shortage. But a longtime resident reports other reasons. The fish elevators on dams built on the Caspian’s tributary rivers are inadequate and the sturgeon have difficulty getting upstream to spawn. Despite boasts about electronic devices installed to solve the problem, he said, helicopters have had to be used to lift fish over the dams. Poaching, he was told by a recent visitor to the area, is widespread with reports current (hard as that is to believe) of caviar bootleggers in motor boats fighting gun battles with the river police.

Other kinds of waste and inefficiency in the rigid Soviet economy is exposed from time to time in the Soviet press as “self-criticism” or to spur reform. Every Moscow resident has his favorite catalogue of scandals. But none was more shocking to this visitor than the comment of a Soviet physicist who described as “typical” the deterioration of an expensive computer, imported from West Europe, which was left outside his laboratory in the snow and rain for six months in its original packing cases until the bureaucracy decided what to do with it.

A study of Soviet construction problems published in the important Soviet journal “Economic Problems;’ Issue No. 3, 1973, showed that the average time for building a medium or large industrial plant in the Soviet Union is 10.6 years! The study analyzed 5,391 industrial construction projects costing more than $3.3 million each and found that it took 9.4 years to build oil extraction plants, 11.9 years for electric power plants, 12.4 years for oil refineries, 14.6 years for nonferrous metal plants and 15.3 years for iron and steel mills.

The study urged maximum use of prefabricated units to speed construction work, especially prior assembly of entire sections of the roof, since delay in getting the roof installed means that expensive equipment, including imported machinery, will lie around in the open for years, turning to rust.

The construction delays, the study added, also meant that the machinery for which the buildings were designed was likely to become obsolete by the time the plant was built. This results in further delays and cost overruns for redesigning and rebuilding the plants.

Not all industrial plants take that long to build, of course. The new FIAT plant on the Volga at Tolyatti was put up in record time with Western help. It is now making FIAT-126 Zhigulis at an annual rate of 660,000, out of a total Soviet output of 905,000 passenger cars planned for 1973. According to a London Times correspondent, “prolonged contact with Italian management, technical personnel and skilled workers has taught tens of thousands of Russians more about western efficiency and how to do a job properly than all the perpetual surfeit of pep talk.” moreover, “millions of people have been prodded out of the rut of routine indifference and spurred to greater effort by the mere prospect of owning one of these buggies.”

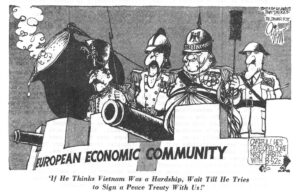

But a quick calculation shows that even if 1973 production plans are achieved, the Soviet Union will be producing less than one-tenth as many autos as the Common Market and it would take the Soviet Union seventy years to build as many cars as Americans now possess.

It is clear that the Soviet consumer has a long way to go. The Ministry of Light Industry was taken to task last year for poor performance and again last month by the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist party. While output was up 9.6 percent, much was lacking in the quality and range of goods, the Committee found. Clothing and shoes particularly failed to conform to the requirements and taste of the market. Shoddy and unstylish products were piled up in warehouses and on store shelves and could not be sold, causing heavy financial loss to the state.

Of all the problems that face Russia’s leaders in their effort to import Western technology to rescue the Soviet economy, none is more difficult than finding a way to pay for the increased imports. Import needs are virtually unlimited, but the country’s export potential is small. The Soviet Union is in the market for turnkey plants for the production of a wide variety of consumer goods but asserts it can only pay for them in the products of the imported plants. West Europe’s Common Market has demonstrated that the biggest growth opportunities for the exports of advanced industrial countries are the markets in other industrial countries for much the same manufactures those countries themselves produce and export. France, for example, buys automobiles from Germany and sells automobiles to Germany. But the design and quality of Soviet manufactures, aimed at a captive market at home, has not been high enough in the past for significant exports of finished products to the West.

With Russia’s capability for this kind of trade limited at present, the Kremlin sees the USSR’s biggest export potential in raw materials, such as oil, natural gas and minerals. It is an extraordinary turn of events, for it has led the world’s second most powerful nation to act like an underdeveloped country, inviting advanced capitalist countries of the West to provide capital and technology to develop the Soviet Union’s natural resources. The extracted raw materials are supposed to repay the investment (with profit), supply increased Soviet needs and provide a surplus for export to pay for Russia’s increased imports.

West European diplomats raise some pointed questions about this Soviet plan and the degree to which it would serve the American objective of “interdependence” as a restraint on Soviet policy abroad.

Over the next five to fifteen years, they note, American food shipments will be helping to protect the Soviet leaders from the consequences of their mismanaged agricultural policy. American capital and technology will be building up the Soviet resource base, enabling the Politburo to divert Soviet capital to other economic (and military) objectives. What assurance is there that, once this has been achieved, the next generation of Soviet leaders will not turn on the West and resume, from a much strengthened posture, an aggressive policy?

Secondly, the West Europeans note that the first stage of the Soviet proposals calls for Russia to get American capital and technology to develop Soviet resources. The payoff to the United States in natural gas and other raw materials comes later. Once the investment has been made, they ask, will not the United States have more to lose than the Soviet Union if it comes to a break?

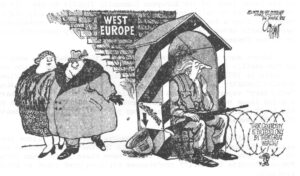

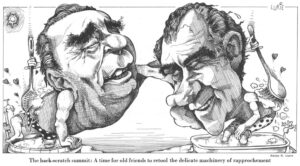

Moreover, the détente, in Soviet eyes, has narrow limits. Determined precautions are being taken to avoid any political repercussions at home from increased contacts with the West as economic cooperation proceeds. Since President Nixon’s May 1972 visit to Moscow, the chiefs of the Soviet armed forces and the Soviet security police (KGB) have been made members of the Politburo. It can be argued that Brezhnev’s purpose was to commit them to the détente by making them co-responsible for it. But their influence on policy undoubtedly has been increased and they may have exacted a price in advance for going along. The military price may be discovered in the course of the SALT II and mutual force reduction negotiations. As for the security police, it is clear that they have been granted — perhaps with no great reluctance — authority for the most severe crackdown on dissenting intellectuals since the Krushchev era.

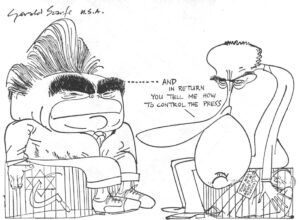

The ambivalent nature of Soviet policy was brought home sharply to a panel of American businessmen, scholars, journalists and former high government officials which met recently in Moscow with representatives of some of the Soviet Union’s most prestigious research institutes on international relations. At the end of the three-day conference, the Soviet co-chairman recited a long list of topics on which the two sides, in his opinion, had found sufficient common ground to justify further discussion and attempts to reach agreement. But there were two issues, he stressed, on which differences were fundamental and undoubtedly would remain. One was Soviet rejection of the Western concept of “freer movement of people and ideas.” The other was the Soviet determination, despite détente and a policy of “peaceful existence”’ to pursue the “ideological struggle” at home and abroad.

In a private conversation later, one American participant told the Soviet co-chairman that he saw two contradictions that might defeat the Brezhnev policy.

Firstly, he said, he doubted that Soviet-American cooperation would get very far if the Soviet Union continued to insist that economic cooperation and political warfare could go on side by side. Just as military disarmament was being approached through arms control negotiations, a first step toward ideological disarmament might also be necessary, perhaps in the form of rules of conduct for the “ideological struggle,” establishing some degree of parity. At the moment, the Soviet Union had easy access to the open societies of the West and could wage its “ideological struggle” without hindrance. But it was intensifying repression of Western and other unorthodox ideas in the Soviet Union and objecting to broadcasts of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty — while keeping Radio Moscow going at full blast.

Secondly, while Nixon and Kissinger talked of economic and other forms of interdependence as restraints on the foreign policies of both sides, the current Soviet Five Year Plan, as those of the past, sought a degree of self-sufficiency that approached autarchy. There was no indication of a Soviet effort to build up export-oriented industries and large-scale trade in manufactures with the advanced countries. Yet that was the only way to finance large-scale imports and give some play to the principle of comparative advantage, which could give Soviet consumers the benefit of some cheaper and better food and manufactures than could be produced at home. The joint Soviet-Western projects suggested by Moscow for development of Soviet natural resources would not go far in this direction.

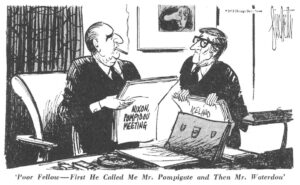

The Soviet co-chairman made no reply to the criticism of autarchy, but the comment may have been referred higher. Several weeks later, in a speech on West German television during his visit to Bonn, Leonid Brezhnev said: “Our plans are by no means aimed at autarchy. We are not following a policy of isolating our country from the outside world.”

It is interesting to note Soviet sensitivity to the charge that the policy of autarchy, practiced since Stalin’s early days, is inconsistent with the interests of the Soviet consumer as well as the interdependence the Nixon-Kissinger policy seeks to create. But there is little evidence as yet that Soviet policy has changed. The question, as put by Austrian diplomat Walter Wodak in connection with Western and neutral proposals at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, is this : “Will (the Soviet leaders) now, having achieved military equality, and their security needs being recognized, take part as equal partners in the international division of labor, drop their policy of self-sufficiency and devote their wealth and productive capacity to raise the standard of living of their people?”

As for the “ideological struggle,” the Soviet co-chairman said he saw no reason why it could not continue side by side with economic cooperation. In any event, there was no alternative. In a vague allusion, he conveyed the idea that there were various views among Soviet policy-makers — as had been reflected surprisingly among the Russians at the three-day conference — and he indicated that Russians skeptical about the détente policy were more comfortable with it when assured there would be no easing of the “ideological struggle.” He urged that too much attention not be paid to this. Philosophy, he said, is one thing, actual policy another. Policy was more important. All problems would not be solved at once in Soviet-American relations. Some could be solved in 1973. Others might have to wait for the year 2003.

The prospect of 30 more years of Soviet political warfare abroad and intensified repression of dissenting intellectuals at home is unlikely to arouse much enthusiasm in the West, however. A severe strain already has been put on the Nixon-Brezhnev détente policy by the current increase in arrests, trials, public confessions, commitment of some dissidents to mental hospitals and attempts to intimidate others, including nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov and Nobel prize-winning novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

To Be Continued

Received in New York on October 5, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, The Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.