London, England May 23, 1973

Within days after Secretary of State George Marshall in 1947 called on Europe to unite for a joint attack on its problems, Foreign Secretary Bevin of Britain was assembling the leaders of the continent for a meeting in Paris to draft the response that led to the Marshall Plan and, later, to NATO, the Coal and Steel Community and the Common Market. If the response appears somewhat slower one month after Henry Kissinger’s April call for a comparable “new era of creativity in the West,” no one could be surprised. To unite to receive American aid naturally was easier than to unite to give aid to America, more blessed as that might be in the eyes of heaven and Richard Nixon.

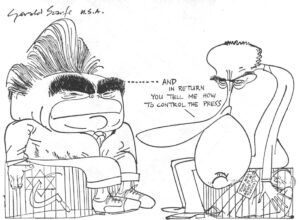

A high British Official, whose frankness has been increased by his approaching retirement, described it to a large not-for-attribution lunch with American correspondents the other day as “a bit of blackmail” to obtain “economic concessions in return for leaving American troops” and the American nuclear umbrella in Europe.

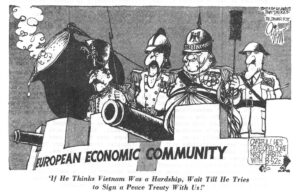

Dr. Kissinger argues that “the political, military and economic issues in Atlantic relations are linked by reality, not by our choice…unbridled economic competition can sap the impulse for common defense.” To Treasury Undersecretary Paul Volcker, economics and defense are linked by the deficit in the U.S. balance of payments, which he sees as the central issue in American relations with West Europe, as with Canada and Japan. Trade barriers abroad, overseas defense expenditures and an “unfair” world monetary system, in his view, are the sources of that deficit; eliminating it requires action on all three accounts.

To Europeans, a fourth account, American investment abroad, is the chief source of the American payments deficit. They have been pressing for years for tighter American controls on the outflow of long-term capital which, they argue, has spread inflation around the world, has enabled American companies to buy up great numbers of plants abroad and has left central banks of other countries holding the bag to the tune of 70 billion inconvertible dollars. The Nixon Administration has ignored this angry complaint — and worse. When the British, French and West German Finance Ministers wound up their difficult negotiations with Mr. Volcker in Paris during last February’s monetary crisis, agreeing finally to his demand for a further ten percent devaluation of the dollar, they were astonished and infuriated to hear him say, virtually as he walked out the door, that the weak American controls on capital-outflow — which Europe was urging Washington to tighten — would be removed entirely by the end of 1974.

The February devaluation, the Allies are convinced, has left the United States with an undervalued dollar that will put the American trade balance in surplus next year, once the usual “J-curve” time-lag has passed, without trade or further monetary concessions by other countries. Moreover, a new world monetary system cannot be shaped to benefit one country, it is argued, nor is there any basis for granting unilateral trade advantages to the United States under the GATT rules, which provide for the exchange of reciprocal concessions. Treasury Secretary Shultz’s announcement that he would insist on a net American advantage in the approaching trade negotiations and had purposely left the word “reciprocal” out of the Nixon Trade Bill — for the first time since the trade liberalization program was initiated four decades ago — has confirmed some of West Europe’s worst fears.

All this disputation — which conceals as much as it reveals about the real issues between the United States and its Allies — makes cheerful reading in Moscow. Soviet analysts predict a falling out within the decade by the three great “imperialist” rivals — the United States, the European Community and Japan — and, possibly, an economic form of “imperialist war.”

All this disputation — which conceals as much as it reveals about the real issues between the United States and its Allies — makes cheerful reading in Moscow. Soviet analysts predict a falling out within the decade by the three great “imperialist” rivals — the United States, the European Community and Japan — and, possibly, an economic form of “imperialist war.”

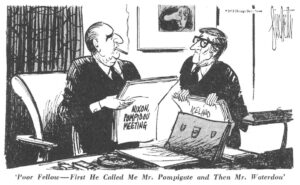

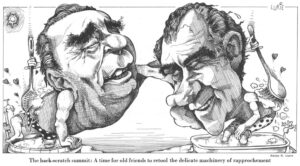

The Kremlin’s game in these circumstances is to play all sides against the middle, It is offering Siberian oil and a peace treaty to Japan. Détente and trade are proffered to the Common Market countries individually — Brezhnev’s trip to Bonn, the first ever by a top Soviet leader, has followed his exchange of visits with President Pompidou of France and the new thaw in relations with Britain. Meanwhile, ignoring Watergate, Mr. Brezhnev is preparing to go to Washington and Soviet scholars and commentators are suggesting privately and publicly that the two superpowers have a joint interest in keeping the European Community from getting too big for its boots.

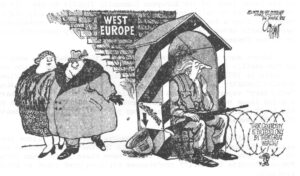

Does the idea of a superpower gang-up on the European Community reflect wishful thinking in the Kremlin? Perhaps. But at least one important Common Market Ambassador in Moscow suspects that Soviet talk of a common Russian-American policy of hostility toward the European Community may reflect private Soviet-American discussions. He was sufficiently concerned to warn this visitor recently that any yielding by Washington to Russia’s siren song could set off a race to Moscow by West Europeans, neutralization of part or most of Western Europe and the expulsion or withdrawal of the United States. This scenario is known here now as that of West Europe’s “Swedenization,” the step that ultimately leads to its “Finlandization” under Soviet pressure.

Nixonian rhetoric has contributed to Europe’s concern. The President may have thought he was comforting America’s allies when he described his new trade bill as preparation for a move from “confrontation to negotiation” in the field of trade. But West Europeans remember that he first used this phrase in 1968 to describe his plan to defuse the cold war with the Communists. Does Mr. Nixon feel that American and West European interests now are as antagonistic as Soviet-American and Sino-American relations in 1968? Probably not. But the Allies note that he has been equating the Common Market and Japan with the Communist powers as America’s rivals ever since an extemporaneous Kansas City speech on July 6, 1971 that went unreported until after the drastic monetary moves of August 15.

Dr. Kissinger has gone to some pains recently to reinterpret and, for the first time, to publicly disown authorship of this simplistic pentagonal balance-of-power concept which reflected far more the views of the President’s two chief advisers then on international economic affairs, John Connally and Peter Peterson. Dr. Kissinger was on his way to Peking at the time and, as the New York Times reported soon afterward, first heard about this little-noticed speech from Premier Chou En-lai.

“As we Look ahead five, ten and perhaps 15 years, we see five great economic superpowers: the United States, Western Europe, the Soviet Union, mainland China and Japan,” Mr. Nixon said. “We face a situation where four other potential economic powers can challenge us on every front.”

It was a view that recurred frequently in Presidential speeches during the monetary and trade confrontations with West Europe and Japan from August 15 to December 1971. It was restated in other ways that left little doubt of its meaning, political as well as economic.

“I think it will be a safer world and a better world if we have a strong, healthy United States, Europe, Soviet Union, China, Japan, each balancing the other, not playing one against the other, an even balance,” Mr. Nixon said on another occasion.

Seen from Europe, it sometimes seems as if the Nixon Administration has moved the United States from enmity with the Communist powers and friendship with West Europe into a “limited adversary relationship” with both. There is a widespread feeling that a quarter-century of American support and encouragement for West European union has given way in the Nixon Administration to a policy of public lip service to European integration, accompanied by private hostility.

“The Americans have shown repeatedly, and recently with their monetary maneuvers, their will to block European integration,” one of the architects of the Common Market, former Christian Democratic Premier Emilio Colombo, told his colleagues in the Italian cabinet in late February.

In one recent private meeting here, a knowledgeable Washington official acknowledged that the Nixon Administration regards this period in relations with the Communist powers as an “era of maneuver” more than as an “era of negotiation,” a phrase he said was coined for public consumption. The Nixon-Kissinger team exploited China’s fear of Russia to initiate relations with Peking, a move which in turn induced Moscow to reinsure its relations with the United States, But Mr. Nixon’s idea of balance-of-power politics is not limited to the Communist giants, as we have seen. As West Europeans study the proposal for a “new Atlantic Charter,” they wonder what kind of “negotiation” Mr. Nixon has in mind for them. Just as China and Russia have been played against each other to American advantage, Washington’s shift from the cold war to the gold war has aroused suspicion that an attempt is underway to divide and outmaneuver the European Community, rather than to revitalize a partnership of equals between the United States and a uniting Europe.

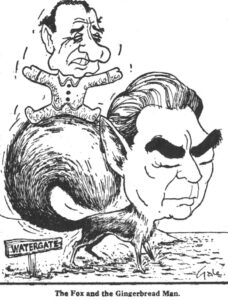

Watergate, of course, has fueled Europe’s suspicions of Administration duplicity, as has the return of John Connally to the President’s side as chief political adviser. The bombing of North Vietnam soured the transatlantic relationship, starting in the Johnson Administration. But the current unprecedented love-hate atmosphere dates from the Connally performance of 1971-72 that he himself described as “bully-boy on the manicured playing fields of international finance.”

Nevertheless, the United States still possesses an enormous reservoir of good will in West Europe. Polls last winter in the Common Market countries showed that, despite declining affection for Washington, Europeans everywhere, including those in Gaullist France, still retained, as since World War II, more confidence in the United States — far more — than in each other. Although Chancellor Brandt’s Parliamentary leader, Herbert Wehner, described the Kissinger “Atlantic Charter” speech as “a monster,” there never was any doubt but that the new American turning toward West Europe, whatever problems it poses, would set in motion a profound joint reappraisal of the relationship. As long as Mr. Nixon remains President, the Allies are unlikely to permit either the current Watergate disclosures or past friction to block the transatlantic dialogue. They will, of course, seek to hedge their bets on commitments requiring Congressional approval until that approval is forthcoming.

Although they are of two minds about Mr. Nixon, Europeans tend to take Hamlet’s view in preferring “those ills we know to those we know not of.” As London’s Sunday Observer editorialized on May 20:

“In considering whether or not to press for Mr. Nixon’s departure from office, the American public, his own party and his Democratic opponents face a genuinely difficult question. In world affairs, Mr. Nixon, with the help of the outstandingly able Dr. Kissinger, has set in train remarkable developments: above all the rapprochement with Russia and with China simultaneously, the search for agreed limits on nuclear weapons, and the American withdrawal from Vietnam with some semblance of peace achieved there…in Europe, he is now about to face a series of difficult negotiations over trade, currency and defense relations.

“It must be admitted that the Nixon-Kissinger team has been more skillful and successful in international affairs than any recent predecessors. It is impossible to believe that the less experienced and less talented Spiro Agnew could hope to continue their success if he became President. He would also be likely to be more reactionary and divisive in domestic affairs….

“If the next three years see America paralyzed, we cannot expect to see big advances made in vital areas of world relationships.”

Received In New York on May 29, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from the New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, the Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.