London, England September 17, 1973

The debate among Western analysts in Moscow over the origins of Russia’s current policy of détente abroad and repression at home — and its likely durability — now centers, the visitor finds, around a thesis attributed to Henry Kissinger’s former deputy and chief Soviet expert, Helmut Sonnenfeldt. This thesis holds that the change in Soviet foreign policy stemmed from critical economic problems and a decision by Mr. Brezhnev and his Politburo friends in the early months of 1971 to give first priority in foreign policy for the next five to fifteen years to the acquisition of American technology. The 24th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party adopted this line in March 1971 and by May, Moscow had made its first major concessions on Berlin, on acceptance of mutual force reduction talks for Central Europe and on SALT. In contrast, during 1970, Moscow engaged in a series of confrontations with the United States: missile cheating at Suez, Syrian tanks encouraged to invade Jordan, Soviet missile submarine bases building in Cuba etc.

A quite different analysis of Russia’s primary motivation is advanced by two of the most respected British and American Sovietologists in Moscow. Without belittling Soviet economic needs, they attribute the Brezhnev policy primarily to intense concern over China dating from the armed clashes along the Ussuri River in February 1969.

Détente in the West, this view holds, appeared essential to the Kremlin to avoid the possibility of a two-front war; China’s rapprochement with the U.S., starting with the first Kissinger visit to Peking in July 1971, made Soviet-American détente even more urgent to Moscow.

A third Western view is that Moscow’s primary objective, dating from acceptance of the U.S.-proposed SALT talks in the summer of 1968, has been to halt the expensive and dangerous nuclear arms race while achieving strategic parity with the United States. The SALT talks would have opened at the Summit in September 1968, rather than in the fall of 1969, and Lyndon Johnson would have been the first American President to visit the Soviet Union, rather than Richard Nixon, had the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia not intervened in August 1968.

A fourth theory, advanced by two well-informed Russians — the deputy director of a key institute of international relations and the foreign affairs commentator of a major newspaper — argued that the turn in Soviet policy began much earlier, in 1963-64. This was the period, following the Cuban missile confrontation, that saw liquidation of the Berlin crisis, negotiation, of the nuclear test-ban treaty and, finally , the ouster of Khrushchev in November 1964 and his replacement by the Brezhnev-Kosygin-Podgorny triumvirate. The trend toward improved Soviet-American relations, according to this analysis, was interrupted by the bombing of North Vietnam in February 1965 and the initiation of large-scale Soviet aid to Hanoi, leading to a strongly anti-American line at the 23rd Congress of the Soviet Communist party in 1966. But despite the hardening line toward America, the search for détente continued through negotiations with the Kissinger-Brandt Grand Coalition government in West Germany, in 1966-67, looking forward to a renunciation of force agreement. Although these negotiations ran into difficulties in 1968 and had to be suspended during the Czech crisis and subsequent invasion, Brandt’s election victory in the fall of 1969 permitted Moscow to reopen that door. Meanwhile, the curtailment of bombing of North Vietnam in April 1968 and the opening of Vietnam peace negotiations in Paris in May cleared the way for Moscow’s June 1968 acceptance of strategic arms talks with the United States and, after two years of ups and downs in relations with the Nixon Administration, the beginning of progress in Soviet-American negotiations.

These four theories, each of which has several variants, are not mutually exclusive, of course. Whether the turn came in 1963-1964 or in 1971, or in between, there is general agreement that Moscow’s motivations in seeking détente with the West have been multiple. But the debate over Russia’s prime motivation has importance nevertheless, for it relates to the depth and durability of the Soviet policy change.

Neither the China conflict nor the SALT agreement nor the West German settlement assures a lasting détente. Bitter and intractable as the Sino-Soviet conflict seems today, the possibility cannot be excluded that a new generation of leaders in Moscow and Peking might succeed in achieving a rapprochement. With China’s leaders over 70 and the Soviet Politburo dominated by men over 65, that change in leadership in both countries could come soon.

A halt in the strategic arms race, if achieved in SALT II, does not preclude a conventional arms race, naval rivalry, competition for political influence around the world or a struggle over Mideast oil. Even a resumption of politico-military confrontation in Europe cannot be ruled out. On the contrary, strategic parity (and the impossibility of either side achieving a first-strike capability against the other) decreases the likelihood that the United States would resort to nuclear weapons to defend threatened allies, including those in Europe, and increases the temptation for Moscow to exploit its conventional superiority in pressure moves or other efforts to increase its influence, even in Central Europe.

It might be thought that the German settlement would at least assure lasting détente between Russia and West Europe. But there can be no certainty here either. West Germany’s acceptance of worldwide recognition of East Germany, its entry into the U.N. and abandonment of Bonn’s Hallstein Doctrine (which threatened a break in relations with countries recognizing East Germany) are virtually irreversible moves. But the modus vivendi over Berlin could be repudiated by Russia, if resumption of pressure there appeared profitable. West Berlin’s geographic vulnerability, as an island of freedom 110 miles within Communist East Germany, cannot be eliminated.

As a result, the Sonnenfeldt thesis that critical Soviet economic needs are central to Moscow’s détente policy, if true, undoubtedly offers the greatest hope of lasting tranquillity. Economic cooperation could lead to steadily increasing interdependence; as an ongoing affair, it theoretically could be delayed or interrupted if détente were threatened.

The Western questioning of the durability of détente has not been ignored by Moscow. The answers -most clearly expressed by Georgy Arbatov, director of the Institute of U.S. Studies of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, in recent articles in Pravda and Kommunist — start with flat denials that the détente policy is “a cunning trick on Moscow’s part designed to lull the Americans’ vigilance.” Mr. Arbatov admits “a grain of truth” in skeptical comments noting “that periods of a certain thaw in relations between the USSR and the USA, immediately proclaimed as the ‘spirit of Geneva’, ‘spirit of Camp David’ or some other ‘spirit’ had been observed in the past as well…and were followed by periods of heightened and not infrequently highly dangerous tension.” But he argues that this time the détente “has a future” because the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. have discovered “spheres of parallel or coincident interests” and have reached concrete agreements in three of them: prevention of nuclear war, limitation of the arms race and the sphere of “economic, scientific, technical and cultural cooperation.”

Leonid Brezhnev went further during his June visit to the United States. Quoting an April document adopted by the Soviet Communist party Central Committee, the Supreme Soviet Presidium and the Council of Ministers, he told Americans that Moscow’s objective was to make the détente “permanent” and “irreversible”.

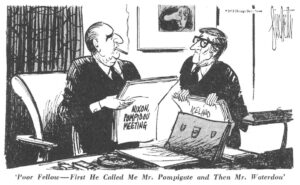

But a month later there was an interesting contrast between two Arbatov comments, one in an English-language broadcast on Radio Moscow beamed to the United States, the other in the Soviet Communist party central organ, Pravda. Both statements stressed the profound nature of the change in Soviet-American relations and the durability of the détente; the broadcast to the U.S. specifically rejected the suggestion of “some Western observers” that the détente is “temporary” .But there was no mention in the broadcast -as there was in Pravda — of Mr. Brezhnev’s determination, despite détente, to pursue the struggle for a Communist world.

“The active development of Soviet-American relations in all spheres where common interests exist,” Mr. Arbatov wrote in Pravda on July 22, “does not erase fundamental class differences…. It is a matter of states divided by profound differences in their socioeconomic systems, politics and ideologies, of states belonging to two social systems between which an historically inevitable struggle is underway and will continue.”

He then repeated his favorite Brezhnev quotation: “The Communist party of the Soviet Union has always held, and now holds, that the class struggle between the two systems — the capitalist and the socialist — in the economic and political, and also, of course, the ideological domains, will continue. That is to be expected since the world outlook and the class aims of socialism and capitalism are opposite and irreconcilable.”

A close reading of Mr. Arbatov’s recent writings reveals another interesting thesis, which he attributes to the official “documents” of the Soviet Communist party and “the international Communist movement” .it is that the “increased (military) might of the Soviet Union and of the entire Socialist community, the vigorous actions of the international working class and the national liberation movement” have altered “the correlation of forces in the world arena…in favor of socialism.” This “important shift in the balance of world forces” has opened up “new favorable opportunities.” The “change in the correlation of forces is not some abstract formula but a tangible reality which makes it possible to secure major positive changes in the international situation” through, in part, “the political application of an increased might.” On one hand, Mr. Arbatov’s documents argue, the capitalist countries have been forced to accept the policy of “peaceful coexistence” which permits Soviet pursuit of the class struggle without risk of war. On the other hand, the détente policy “is creating the most favorable conditions” for “building the new society,” i.e. achieving a Communist world.

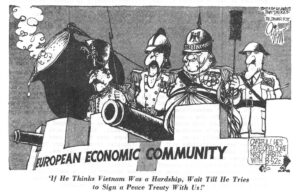

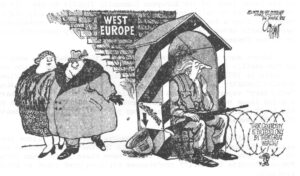

Moscow’s continued commitment to the struggle for an “inevitable” Communist world naturally stirs doubt in West Europe about the meaning of the Kremlin’s détente policy. Fears of Communist subversion or a major Soviet military attack have receded, even if they have not disappeared. But they have been replaced by concern about the so-called “Finlandization” of West Europe, if defense cutbacks in NATO, progressive American troop withdrawals and the declining credibility of the U.S. strategic deterrent shift the balance of power decisively in Russia’s favor.

Just how this might come about has been the subject of much discussion in NATO countries. It is assumed that the Soviet Union would be cautious in “the political application of increased might, “lest it provoke renewed defense measures in the West.” Chancellor Willy Brandt of West Germany has never concealed his view that détente plus defense equals security, a view shared by President Pompidou of France and Prime Minister Heath of Britain, even if all three leaders are under political pressure to reduce defense budgets and terms of military service. A new crisis might not only ease this pressure on defense budgets but even stimulate movement by the nine Common Market countries toward a European Defense Community and some form of European nuclear force, something the Kremlin is anxious to avoid.

One theory of how Soviet political influence might be exerted stems from the Soviet emphasis in recent years on agreements with individual Western countries — and, now, at the 35-nation Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe — on broad general principles of behaviour. The principles are so general as to have little value except in the manner in which they are interpreted.

“The relative supremacy of the Soviet forces in Europe, in a global system of nuclear parity with the United States, would be the means to induce all European states to accept an interpretation satisfactory to the U.S.S.R., ” a French diplomat argues. “This influence could be exerted without any show of force. The mere existence of this force would be sufficient to give the undertakings a value and a permanence which they do not possess in themselves. Such a method could be reinforced by even more efficient measures: agreement on force limitations and control, economic agreements, etc. Its value lies in it being able to provide, without any risk of conflict, or even of crisis, means of developing influence, which in turn could tend to alter the overall balance.”

Soviet success in this design, if this is the Kremlin’s strategy, is by no means certain. Much depends on what the West does. If the Atlantic Alliance is revitalized, if a substantial American presence is maintained, if NATO cohesion overcomes U.S.-European disputes, if progress toward economic, political and, ultimately, defense union in West Europe continues — the Soviet momentum can be checked. Much also depends on the effect of détente, interdependence and increased contacts on the Soviet Union and East Europe. Increased repression in the Soviet Union undoubtedly reflects the fear that any increase in contacts may provoke a liberalizing reaction. Yet, without liberalization, there is doubt whether critical Soviet economic problems can be solved. Imports of Western capital, machinery and technology can help. But the real need, in the view of some analysts, is to reform the organization and management methods of the consumer goods industries, agriculture and the distribution system, then to follow the West toward the post-industrial society with a shift from production to services, from blue collar to white smock, from resource-based to brain-based industry. The inventiveness and innovation this will require cannot easily thrive in a society that severely curtails the free interchange of ideas at home and limits to the absolute minimum travel and contact with the outside world.

To Be Continued

Received in New York on September 25, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, the Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.