May 21, 1973

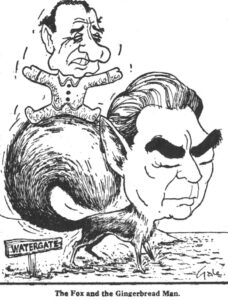

Watergate has raised many questions here about the prospects for the Nixon Administration’s long-heralded and increasingly controversial “Year of Europe,” particularly whether the President can still win the Congressional support essential to it. But it is evident now, despite confused initial reactions, that Henry Kissinger’s proposal for a “new Atlantic Charter” has accomplished its primary purpose. It has thrown a very large pebble into the European pond. Within the European Community and its nine member governments, which have long been preoccupied with domestic concerns, it has commanded the kind of attention that European-American relations have not received since the clash of Gaullist and Kennedy “Grand Designs.” An intricate negotiation is getting underway that promises to be as difficult as it is crucial for the future American role in the world.

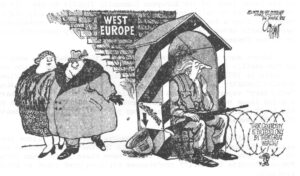

Even before the recent Watergate disclosures, President Nixon was forced successively to postpone his projected 1973 visit to West Europe’s leaders from February to July to Autumn and now to “toward the end of the year.” Apart from the delays in the Vietnam settlement and the Christmas bombing of Hanoi, which was deeply repugnant to Europeans, the projected “Year of Europe” itself aroused controversy from its earliest mention. It is a year that the Common Market’s executive Commission predicted would be one of increasing tension in West European-American relations. Secretary Rogers later said he preferred to term it a “Year of Building,” to achieve better relationships everywhere, not just with West Europe. Others were less interested in the title and more pessimistic about Alliance prospects. Mr. Nixon’s call for a carrot-and-stick Trade Act – to enable him to raise or lower import barriers to extract concessions from America’s closest allies – led London’s Sunday Times to comment that “the ‘Year of Europe’ begins with a shock treatment.”

It is a “year” that probably will last a decade. The “new Atlantic Charter,” if it can be agreed at a Summit Conference by December, will only be a declaration of intent to seek solutions in common. The solutions themselves will not be easily found to issues, long ignored, that increasingly divide Washington from the chief NATO allies. Among them are problems of NATO’s defense posture, military security in Europe, other negotiations with the Communist powers, relations with Japan, instability in the Middle East, disarmament, trade, agriculture, monetary crisis-management and long-term monetary reform, funding the $70 billion American debt abroad, foreign investment, inflation, the energy crisis, the environment, regulation of multinational companies and aiding the developing countries.

“In 1973,” said the State Department’s latest annual report, “we will be initiating new negotiations and developing new relationships which could determine the political-economic structure of the world for the remainder of this century.” It is a large enterprise and the difficulties loom even larger.

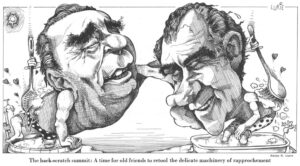

In his first Administration, Mr. Nixon devoted himself abroad primarily to negotiating with adversaries — Moscow, Peking, Hanoi — and did so with extraordinary success. Negotiating with Allies, the priority task for the second Nixon Administration, is something the White House finds much more difficult as has been acknowledged by one of Dr. Kissinger’s deputies, Helmut Sonnenfeldt. He speaks with authority having, he recently noted, “clocked” 70 hours over the past year in U.S. face-to-face negotiations with Soviet Communist party Secretary Brezhnev -and many times that number of hours in inter-Allied discussions. The White House aide, who now is to become an undersecretary of the Treasury, first made his startling comment about negotiating with the Allies at a private conference in December and it was thought to be a semi-jocular remark. But his repetition of the criticism at other private meetings since then has made it evident that he was in deadly earnest.

In part, Mr. Sonnenfeldt was expressing the repeated exasperation American officials have felt in attempting to negotiate with a European Community of nine nation states (or a NATO Eurogroup of ten), which is unable to speak with a single voice until, after infinite haggling, a compromise position is agreed unanimously. And then the trouble usually has just begun: almost equal strain is experienced every time the negotiations call for some shifting of ground.

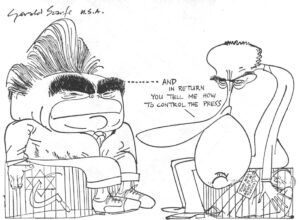

Europeans are equally exasperated by the difficulties in consulting with the Nixon Administration. Washington, in any Administration, has never been a stranger to divided counsels. “Treaties” among a half-dozen government agencies sometimes must be negotiated before an American position can be presented abroad. The United States, of course, has an advantage over the European Community: when disagreements persist, as they often do, the President can decide. But in the Nixon Administration, Europeans complain, this has not been an advantage but an added impediment, one that Watergate is unlikely to remove in foreign affairs, even if the functioning of the White House staff is reformed in the domestic field. White House foreign policy decisions have often ignored interagency discussions and have been held so closely that State Department and other officials — including Dr. Kissinger’s own assistants at times — have not been consulted in advance nor even informed later of the full background.

“That’s all right for dealing with Communist dictators, who operate in the same way and can’t complain about being taken by surprise,” said a British diplomat in Brussels recently. “But it can make consultation among democratic governments virtually impossible.”

In past Administrations, European leaders often were informed of interagency discussions in Washington in time to gain consideration for Allied views before final American decisions were taken. “The Americans do not like to decide alone; they like to discuss first,” visitors in the first two postwar decades often were told by Jean Monnet, the father of the Common Market. He spoke from firsthand knowledge as cosponsor of many major European-American enterprises in political, economic and military affairs. The British-American “special relationship” for decades was largely based upon the skill with which London practiced this art of consultation. In this process, British Ministers, as generalists for the most part, heavily depended on their nonpolitical civil servants for expert analysis and advice. Before meeting with American cabinet members, they expected officials lower down on both sides to have reached substantial agreement on the facts, to have informed each other of their respective ministerial views and to have resolved most issues in advance with formulas jointly devised then separately cleared with or “sold” to their superiors. The British and American cabinet members, on meeting, then were able to deal with the remaining questions, usually political rather than technical, with a clear understanding of each other’s problems and negotiating position. The Nixon-Kissinger system frequently has frustrated this entire process.

Asked recently whether London’s views had been taken into account in an important American decision at the mutual force reduction talks with Russia in Vienna, a key British official exploded: “We’ve never been heard. Until the White House makes a decision, the State Department cannot discuss the American position with us or even inform us authoritatively of the key factors that are being weighed. Once a Presidential decision is made, we are told it cannot be changed.”

The deep suspicions stirred in Europe by the Administration’s methods and unilateral policies were acknowledged by Dr. Kissinger in proposing a new dialogue. “There have been complaints in Europe that America is out to divide Europe economically, or to desert Europe militarily, or to by-pass Europe diplomatically,” he said. “Some of our friends in Europe have seemed unwilling to accord America the same trust in our motives as they received from us.”

Europe’s distrust of the United States clearly cannot be overcome unless consultation is improved. But neither improved consultation nor trust, although essential, will themselves eliminate the substantive conflicts that now divide the Atlantic Allies. Dr. Kissinger touched on some of these substantive disputes in his April speech, but Mr. Sonnenfeldt’s earlier comments, made privately, are considered here to be even more revealing of Administration attitudes.

Mr. Sonnenfeldt was reported to have summed up Washington’s criticism of the Allies under three headings — none of them, of course, the Administration’s fault. One is that the United States feels it is up to its trading partners to remove the permanent deficit in the U.S. balance of payments (something for which the Allies perversely insist the United States too must share responsibility). This Washington view might sound “demanding” or “imperious,” he acknowledged, but it was a reality of American politics that Europe must accept.

Dr. Kissinger’s deputy argued further that West Europe’s monetary and trade policies created “concrete irritants translatable into domestic political issues” in the United States (ignoring those created by U.S. policies in Europe) even when, as in the case of California’s citrus growers, they only involve small sums of money. “If 15 or 20 or 30 groups, each with a few million dollars, think they are suffering disadvantages,” he said, Congressional coalitions of such disaffected groups could prove formidable for the Administration.

Another major fault attributed to the once-poor but now-affluent West Europeans was their failure to act on their altered economic circumstances, and America’s, by taking over more of the defense load in Europe. It is essential, Mr. Sonnenfeldt has insisted, to revise NATO’s strategy, structure, force deployments and burden-sharing arrangements — and for the Allies to absorb the added costs the U.S. incurs by stationing 300,000 of its troops in Europe. If the United States is negotiating with the Soviet Union on European defense, it is not through choice, he said, but because “it has not proved possible” to negotiate about it with the Allies, something he would prefer.

This is not, by far, the whole list of Nixon Administration grievances. But it gives some of the high points and the tone of the “dialogue” — if “dialogue” is the proper word for this slinging match that, on both sides, has been mounting in volume for two or three years.

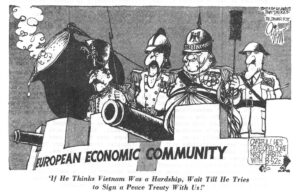

West Europe, of course, has its own catalogue of complaints about American policy. The most important — and most emotional since the Vietnam bombing and the bullying tactics of former Treasury Secretary John Connally — is Washington’s insistence, just repeated by Dr. Kissinger, on the “linkage” of European defense issues to negotiation about trade and monetary reform. Ever since Mr. Connally’s threats to remove American troops from Europe (and, with them, the credibility of the American nuclear guarantee) unless granted unilateral trade and monetary concessions, Europeans have seen the “linkage” of economic and defense issues as a demand for “protection money” and even a form of “nuclear blackmail.”

There are other difficulties in the American “linkage” approach. Monetary reform already is under negotiation in the International Monetary Fund’s Committee of 20, made up of the ten chief monetary nations and about the same number of developing countries: agreement on the broad principles of reform is sought there by September and a complete agreement by September 1974. Trade liberalization is to be negotiated, starting in the Fall, in the 80-nation GATT in Geneva and will take at least until the end of 1975. Apart from the difference in timetables, both GATT and the IMF include Canada and Japan, which account for the bulk of the American deficit in trade and payments, plus the members of the Common Market, the United States and the developing countries. But Japan and the developing countries are not involved in European defense, which obviously cannot be discussed in the IMF or GATT. For defense questions in Europe, there are still other forums. The United States deals bilaterally with Bonn in biannual agreements, now up for renewal again, to offset the bulk of the dollar outflow of American troops in West Germany. Most other European defense matters are handled in the 14-nation North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which is not competent to discuss trade and monetary issues. The nine-nation Common Market has no defense responsibilities and includes neutral Ireland, which is not a NATO member, and France, which remains in the North Atlantic Alliance but has withdrawn from NATO’s integrated commands and defense planning groups. The Common Market, moreover, does not include such NATO members as Norway, Greece and Turkey which, unlike France, are members of NATO’s Eurogroup. France, through military liaison missions, independently coordinates its war plans with the NATO Commands on a bilateral basis.

Thus, Europeans argue, no forum exists or can easily be created to take on the “comprehensive” negotiations the United States has been suggesting for months, well before Dr. Kissinger’s April speech. Furthermore, trade, monetary, diplomatic and defense problems are handled by separate ministries in each of Europe’s governments; the lack of a forum is paralleled by the lack of negotiators competent to discuss all four subjects across the board.

None of these procedural difficulties, however, has dissuaded Washington from its insistence on linked negotiations. On the contrary, they have encouraged the Nixon Administration to propose new machinery for consultation with West Europe, more particularly with the nine-nation European Community. Secretary Rogers last December told the Common Market Commission that the United States favored “operational links” with the Community. He told American officials in Brussels, some of whom suggested that the Common Market countries would prefer more informal arrangements, that President Nixon felt something “highly visible” was essential.

It was Chancellor Brandt of West Germany who interested Mr. Nixon in the idea of an “institutional link” between the European Community and Washington, a project first proposed by Jean Monnet in 1962 and approved later in the 1960s by Parliamentary resolutions in all the Common Market countries except Gaullist France. The Brandt-Nixon Communiqué that terminated their Florida meeting in December 1971 spoke of close cooperation “to be arranged” between the United States and the Common Market; it signaled Mr. Nixon’s private agreement in principle to the concept, urged on him by Mr. Brandt in April 1970 and June 1971 as well, of an institutional link.

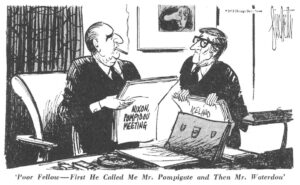

French acquiescence proved more difficult to obtain. President Pompidou had reversed General de Gaulle’s veto of British entry into the Common Market, but he was not prepared then to challenge Gaullist dogma on “independence” from the United States. In the intricate triangular bargaining and shifting alliances on shifting issues that characterized British-French-West German negotiations before and during the Common market Summit conference in October 1972, Prime Minister Heath sided with France on this question. The Brandt proposal for an “institutional dialogue” with the United States was watered down to “constructive dialogue.” As for the linkage of defense and economic issues in the American proposal for “comprehensive” negotiations, Mr. Heath told visitors whimsically before his February 1973 trip to Washington that he saw no possibility in the projected European-American negotiations of the kind of bargaining that goes on within the Common Market, which the British term a “vue d’ensemble” and the French call “un package deal.”

Thus, two missing links — an institutional link and an economic-defense link, both pressed by the United States and resisted by West Europe now impede a necessary evolution in transatlantic relations. Europeans oppose and Americans favor the two links for the same little-stated reason. Both are convinced that an institutional link would create a forum in which economic and defense issues could be linked closely in negotiations, enabling the United States to employ its vital military contribution to Europe’s defense as leverage in economic bargaining. A multilateral European Community Summit conference with President Nixon this year encounters much the same objection in Europe, particularly in France. No forum would be more qualified to discuss both defense and economic issues, for it is at the top in every Government that these issues inevitably must be considered together.

The Nixon Administration, of course, has repeatedly denied any intent of linking political, military and economic issues “for the tactical purpose of trading one off against the other,” as Dr. Kissinger put it in April. But the more Washington denies it, the more Europeans, who have read Shakespeare, become convinced that “the lady doth protest too much.” Whatever the forum and the timetable, it is evident that, along with trade and currency issues, a major reappraisal of West European defense — and the American commitment to it — will be difficult to avoid. For Europeans, even without Watergate, the “Year of Europe” is increasingly beginning to take on the appearance of the “Year of the United States.”

Received in New York on May 29, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, the Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.v