24 May, 1973

The search for solutions to the problems that haunt American relations with the European allies recalls Gertrude Stein’s last words on her deathbed.

“What is the answer?” she whispered. There was a long silence.

“Then,” she finally asked, “what is the question?”

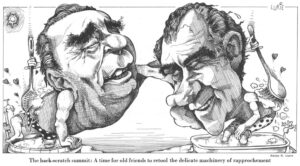

The Atlantic Allies have been seeking answers to their problems with little success and it may be that they are asking the wrong questions. With something like this in mind, Jean Monnet’s Action Committee for a United States of Europe has proposed a new look at the issues by two “Wise Men” named by the United States and the European Community. Their function would be “to investigate, not to negotiate.” There has been too much adversary negotiation across the Atlantic, too much maneuvering and posturing in search of national or regional advantage across the bargaining table. Mr. Monnet’s aim is to put the problems on one side of the table and the two “Wise men” on the other to assemble an agreed data base, analyze the issues and draw up a timetable for resolving them.

“If this work is done,” the Action Committee said, “then the difficulties will be cut down to size. Some of them, will prove to be quite secondary and the necessary negotiations can be pursued in a changed climate to arrive at mutually advantageous compromises.”

The conventional wisdom on both sides of the Atlantic holds that the United States and Western Europe are at loggerheads over economic issues that involve national interests of importance, but that the common political and security interests of the alliance require that these conflicts be resolved or reduced. It is possible that the reverse is the case, that the main difficulties to be solved are in the political and security field and that the presumed clash of national economic interests reflects misperceptions of reality.

What are said to be national economic interests — i.e. the interests of the nation, that is the people — are often nothing but vested interests. The influence of vested interests with governments, and the interests of politicians in the support of various lobbies, have turned domestic political problems into international economic issues. It is generally acknowledged that some of the most difficult so-called “economic” issues between the United States and the European Community have involved piddling sums of money.

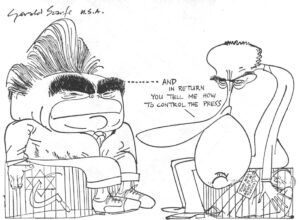

This has been true in past administrations in Washington, but rarely has domestic politics intruded into the nation’s relations with its Allies to the extent that has occurred in the Nixon Administration. One of the angriest struggles with the Common Market involved exports to Europe of less than $10 million a year of California grapefruit. But the shippers were President Nixon’s political friends and campaign contributors. And it was the President’s personal political interest in the issue that led the European Community finally to open its doors somewhat wider to California citrus fruits in 1972, the only significant departure from a decision to grant no unilateral trade concessions, particularly under the threats, bluster and monetary pressures mounted by former Treasury Secretary John Connally.

Larger sums — and larger domestic political stakes — were involved in the textile struggle with Japan that led to the three “Nixon shocks” to Tokyo in 1971. But the economic injury suffered by the American textile industry as a result of ex-Premier Sato’s delay in imposing “voluntary” export quotas was relatively minor and would never have become a major issue between the two governments had Mr. Nixon not been wooing the South and its textile interests as part of his “Southern strategy” for the 1972 campaign.

The limited importance of the “reverse preferences” issue pressed against the Common Market can be seen in the fact that American exports to former French territories in Africa have risen faster than those of France, despite the tariff preferences still enjoyed there by French products.

The Administration’s bitter complaints against the European Community’s common agricultural policy (CAP) are more justified, but they have been exaggerated beyond all reason in a bid for the farm vote. The recent Administration study showing that American farm exports to the Community could rise by $8 billion is a pipe dream. An increase of five percent of that figure, or $400 million a year, is the most that could realistically be expected, according to American experts in Brussels.

The main reason for America’s recent trade deficits and the declining competitiveness of American exports has not been the “unfair” trade barriers about which the Administration complains, but an overvalued currency resulting, in part, from Vietnam war inflation. Devaluation of the dollar, which Washington resisted for years, was the essential requirement. Now that this step has been taken and negotiations finally are underway for reform of the world monetary system, most European analysts believe there will be a return to surplus in the American basic balance of payments before the end of next year.

None of the American trade demands that have generated so much heat, nor all those put together that could realistically be obtained, would be likely to contribute even ten per cent of this payments turnaround. Moreover, none of the trade disputes between the United States and the European Community involves a significant proportion of the gross national product, or a commodity vital to the nation’s health much less its existence, although oil may begin to take on some of this importance in the future.

The very concept of “national rivalry” in trade and economic affairs with vital interests at stake is a misnomer. It confuses the rivalry of national governments with the competition of producers and merchants, which requires intergovernmental cooperation to lower barriers to trade.

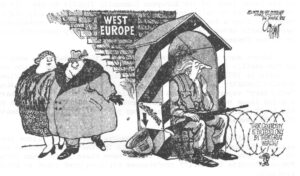

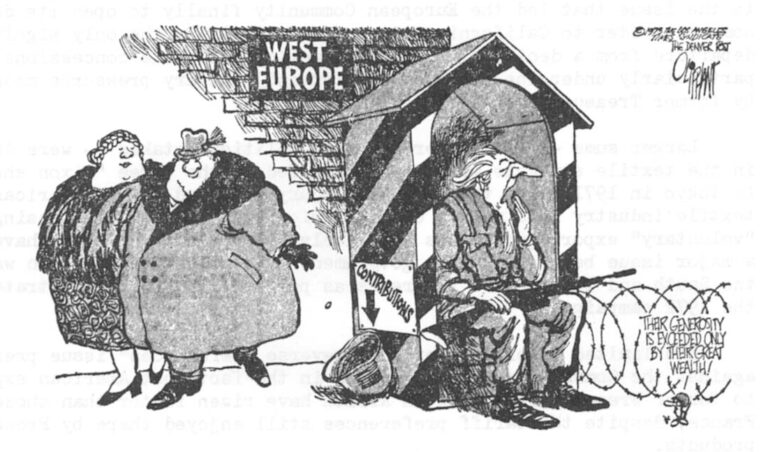

In contrast, the defense and security issues that confront the Atlantic Allies touch the vital interests of all the nations involved. The chief danger lies in American frustration both over Vietnam and over West Europe’s failure, after achieving affluence, adequately to share worldwide defense burdens, including those in Europe. The danger is not so much that of a governmental decision in Washington, but a political evolution in the direction of worldwide disengagement that impairs or terminates the American military presence in Europe and, therefore, the credibility of the American nuclear guarantee. This danger has made the mutual and balanced force reduction talks (MBFR) with Russia a political necessity for the Nixon Administration. And the future defense of Europe is being negotiated with the Soviet Union rather than with the NATO allies.

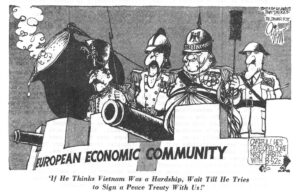

The United States will consult its allies in the course of the talks and lip service will be paid to a “multilateral negotiation.” But the review of NATO strategy that this requires, and upon which the United States insists, is to be an effort to achieve a rational defence structure and an equitable sharing of the burden after the reductions brought about by the MBFR talks, more than a judgment of what reductions are advisable. In this review, claims that Europe provides 80-90 per cent of NATO’s conventional military forces will not carry much weight in private discussions with Washington, although they may be permitted to float publicly to temper Congressional pressure. The American conviction is that Western Europe, with the exception of West Germany, contributed very little usable military power to its own defense and virtually none to the defense of other common interests outside of Central Europe. A lot of money is spent, but most of it is wasted. NATO strategy and NATO tactical doctrines, it is argued, need reexamination.

In this context, the argument over whether the United States wants Europe to be a regional or a global power misses the point. Dr. Kissinger claims that his references in April to a regional role for Europe were intended to be “descriptive rather than prescriptive.” Politically and militarily, Europe has increasingly defined itself as a regional power -despite some occasional residual global pretensions. The real question is how Europe can assume a wider role, which “nobody would welcome more than the United States, if the Europeans wish to play such a role,” Dr. Kissinger has said. That remark undoubtedly applies to Europe sharing the burden; whether it applies to Europe sharing the decisions is another question. Europe’s role in Asia, particularly in relation to Japan, is critical. The Japanese problem presents itself in an economic form, but the political-security consequence of American-European treatment of Japan comprises the most important global responsibility facing Europe outside its own territory and the adjacent Mediterranean region. There is little sign of European willingness to deal adequately with this responsibility.

In the same way, Europe’s resistance to “linkage” between economic and defense issues, while understandable, is probably futile and not necessarily in the European interest. It is futile, because — regardless of the variety of forums in which trade, monetary, diplomatic and security questions will be negotiated — American determination to seek outcomes that define a “total relationship” will make tradeoffs inevitable, despite Dr. Kissinger’s denial that this is the American tactic. It cannot be avoided, furthermore, since emergence from the position of “economic-giant-but-defense-dwarf” — which would require British-French-German cooperation in a nuclear force remains an impossible decision for Europe to take in the foreseeable future and would in any event require two more decades of American protection. Europe undoubtedly is right that America will try to use its defence leverage to extract economic concessions. But it is wrong to ignore the possibility that Europe, as America’s economic equal, could use its economic strength to obtain security concessions from the United States. Relatively minor financial contributions — through a NATO Defense Payments Union — could take the sting out of American troop costs in Europe after a 10 or 15 % MBFR cut and enable the Administration to deliver a lasting recommitment of the United States and its remaining forces to Europe’s military defense and political integration.

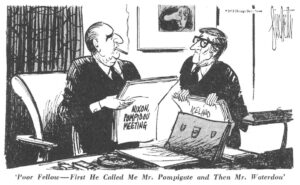

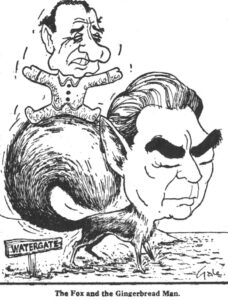

Both the commitment and the treaty in which, ideally, it should be embodies — were it not for Watergate — would require better transatlantic institutions than now exist. The institutions themselves, without a treaty, might bind the United States sufficiently and would certainly restrict unilateral decision-making on both sides. Once Europe sees the advantage of using economic interdependence to bind America to its defense, institutional links would no longer seem a threat. With Political union of West Europe, after a quarter-century of effort, still in its infancy, Europe remains an economic giant uncontrolled by any integrated political brain, thus a danger to itself and the United States. Institutional links between the United States and the European Community would enable the transatlantic partners to manage jointly their increasing economic and social interdependence and to improve diplomatic and military action in the common interest. Realistically this can only be done in the first instance through an arrangement between the United States and the European Community, but the interests of Canada, Japan and other developed countries would have to be discussed with them and taken into account.

Received in New York on May 29, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, the Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.