London, England July 28, 1973

"Actions accepted from an ally whose role is less crucial can produce a crisis of confidence if carried out by a partner occupying a dominant position. When the United States acts unilaterally, disarray in the alliance is almost inevitable. Bilateral United States dealings with the Soviets from which our allies are excluded or about which they are informed only at the last moment are bound to magnify Third Force tendencies."

— Henry A. Kissinger, May 1964

"…the temptation of the Superpowers (is) to regulate, by means of their dialogue, the parceling out of world responsibilities….

"I do not know whether the year 1973 will be the ‘Year of Europe,’ but I am sure that in 1973 the question of the defense of Europe will be hovering in the background of all the talks which will be taking place in Europe and elsewhere…the real debate and the real question concern Europe’s security."— French Foreign Minister Michel Jobert, June 1973

At the end of 1972, the Soviet Ambassador to France paid his farewell calls and boarded a plane to Moscow to take up a new post. Eyebrows shot up all over Paris when the French press reported that a single Western ambassador, going beyond the needs of protocol, turned up at Orly Airport to see him off — the American.

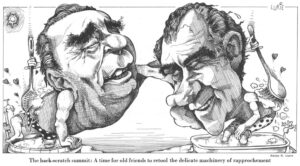

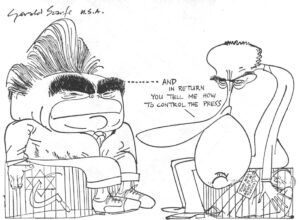

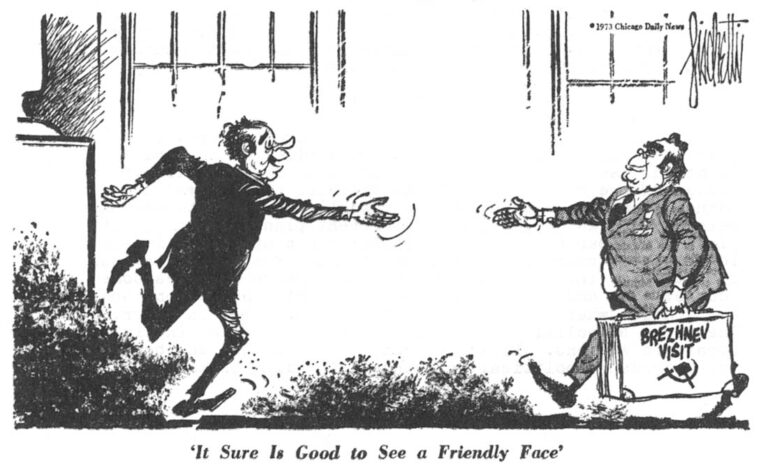

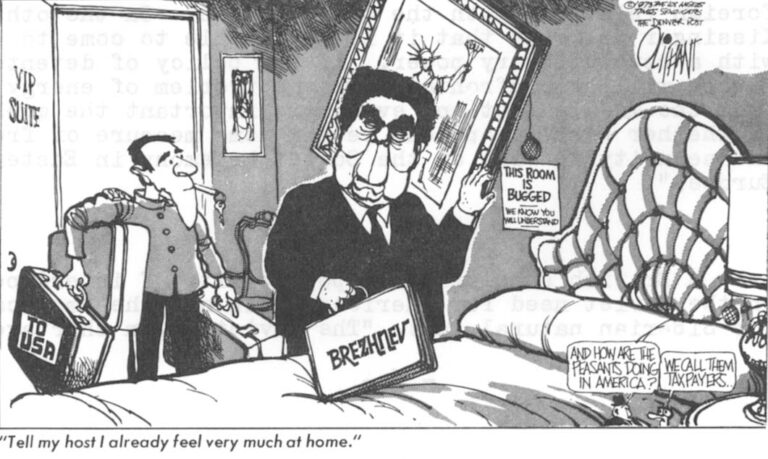

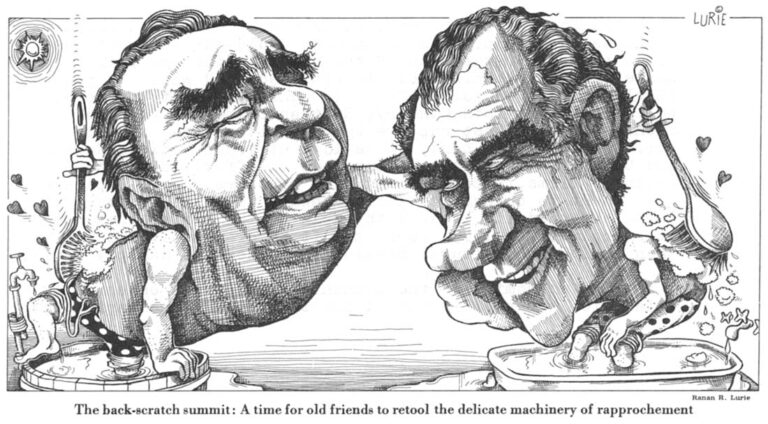

Three months earlier, Henry Kissinger spent 20 hours with Leonid Brezhnev near Moscow negotiating on a wide range of questions, including the timing and relationship between two projected East-West conferences of critical importance to the NATO allies, the Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe and the talks in Vienna on Mutual Balanced Force Reductions (MBFR). On his way back to Washington, Mr. Kissinger stopped in Paris and briefed the French Foreign Minister and President Pompidou on what had happened.

“It was a very good briefing — a tonic for inter-allied relations,” a high French official later commented. “The only trouble was that the Russians briefed us the next day and — as our Deputy Foreign Minister informed the State Department — they told us a lot of things Mr. Kissinger had neglected to mention.”

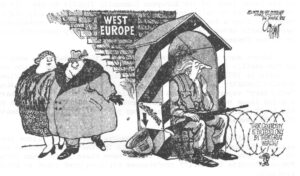

The strain created in America’s relations with its major allies in two short years by President Nixon’s unilateral, secret negotiations with Russia and China is one of the most critical problems facing the Atlantic Alliance in the “Year of Europe.” It might have been faced sooner had not the effort to build bridges to the enemy coincided with the burning of bridges to friends. Seven months after President Nixon’s first letter to Brezhnev in January 1971 and one month after Henry Kissinger’ first secret trip to Peking in July, Mr. Nixon and Treasury Secretary John Connally terminated the dollar’s convertibility into gold and imposed import surcharges that doubled American tariffs overnight. They opened a campaign that blamed most of America’s international economic problems on the country’s chief allies abroad and equated West Europe and Japan with Russia and China as America’s rivals of the future. The “Nixon shocks” to Japan were more dramatic, perhaps, than those to West Europe, but hardly more profound. For Japan, the blow was to pride and to pocketbook. But for West Europe, what was brought into question was not only money and “face,” but the survival of freedom and, perhaps, of civilization itself. For, since 1945, when massive Soviet armies reached the Elbe — where they still remain, only a few hours from the Rhine — West Europe’s military security has depended on the American connection.

Everyone favors détente, of course. No one wants war, particularly nuclear war. But the issues posed by “Nixon’s Ostpolitik” — as by the Eastern policy of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt — are complex. One way to see them in depth, as one travels around Europe, is to listen to the way they are analyzed by a variety of European officials, scholars and journalists and by visiting American specialists.

“Many Europeans fear that a Superpower condominium is being imposed on the world,” said a brilliant young German scholar. “But Washington, which believes that the Soviet Union is fundamentally hostile, aims at a more modest objective, I think, Soviet restraint in world affairs.”

“To encourage and perpetuate restraint, the Nixon Administration seeks to create vested interests in stability and cooperation — a form of interdependence between the United States and the Soviet Union. Both countries favour stability over change. Contrary to the views of some Europeans, the United States does not feel that it has to choose between Western Europe and the Soviet Union in setting priorities for its policy. Washington feels that the concessions it extracts from the Soviet Union benefit the West as a whole. No other Western country can accomplish this.

Many European suspicions about America’s Ostpolitik are unjustified. West Europe has as great an interest in good Soviet-American relations as the United States. True, West Europeans must be concerned that European interests are not ignored or undermined by Soviet-American agreements. The United States wants Europeans to follow her line but often appears reluctant to pay the price of leadership, namely to coordinate policy closely and continuously with her allies at the expense of political flexibility. There is no certainty that creating Soviet vested interests through cooperation will produce the desired effect on Soviet policy toward the West. But there is not even a chance of achieving it if Americans and Europeans fail to coordinate their efforts.”

A British official challenged the belief that both superpowers sought stability. “The concept of stability is utterly alien to the Soviet outlook,” he said. “Restraint is a concept the Soviet Union could accept, but not stability. The Soviet Union will exploit every opportunity to extend its influence, but it may keep its actions within certain ground rules. It is misleading to look at Europe at the present time in analyzing Soviet policy, because Europe is likely to be stable now For some time. But there is no stability in the Middle East, in the Indian Ocean, in ‘the Mediterranean. Linked to the unstable competition in this sensitive area is the vital energy problem of the Western world. Here is where the real danger for the future lies, as the Soviet Union seeks to exploit competition between the United States and the Common Market and Japan for energy sources and trade with the East.”

An American analyst of Soviet affairs suggested that the present period would better be characterized as an “era of political manoeuver” rather than an “era of negotiation.” He added: “Where we are between the extremes of cold war and détente cannot be measured on a unilinear scale. We have to see the relationship as one moving on different planes. Each of these planes is separable from the others: the competition in strategic arms; the competition in conventional arms; the political competition; the economic relationship, which includes some competition and some trade and investment cooperation; and some cooperation where common interests are perceived in other fields. There can be political competition and cooperation in limiting strategic weapons. Political competition itself can be for relative degrees of political influence, depending on the area.

“It would be an error to extrapolate too much from the mood of the 1972 Moscow Summit Conference. The expectations raised there may not be fulfilled completely in stabilization of strategic weapons or in trade. This may raise questions within the Soviet hierarchy about the effectiveness of Soviet policy toward the United States. In addition, as time goes on, local contests may test the thresholds for Soviet restraint. In the West, the attitudes of governments and public opinion may differ widely. There is a need for greater clarity in assessing future prospects and Western aims.”

A high State Department official of the pre-Nixon period noted that Kissinger’s “web of interests” concept of Soviet-American relations represents a major shift from previous ideas. “The Western aim,” he said, “used to be to foster an evolution within the Soviet system. Now the idea is that, without any change within the Soviet system, linkages can be created with the West that the Soviet leaders will not want to break.

“The danger is that the West will be more enmeshed in this “web of interests” than the Soviet Union. SALT I showed than Nixon had to concede more than the Russians. He was more hesitant than Moscow about breaking the “web of interests.”

“As for relations with Western Europe, unilateralism is inseparable from the Nixon concept of foreign policy. It is essential to flexibility. Moreover, it is the mirror image of the earlier American primacy. Psychologically, the feeling of being in charge is now achieved by unilateral action instead of domination. Nixon’s comments and his history suggest that he is uncomfortable with cooperation, more comfortable in a combative relationship. He sees de Gaulle as his model, particularly in style of leadership.”

A Soviet analyst in British Intelligence: “As Moscow sees the world, the Soviet Union has acquired Superpower status. Just as Stalin in 1945 felt it would be a betrayal of the Soviet Union not to exploit the victory of World War II, the Kremlin now feels that it has an obligation to history to exploit Russia’s new Superpower status to change the balance of power in the world. The area chosen for this is Europe and the Mediterranean.

“The first need was to achieve a special relationship with the United States in strategic weapons, control of crises and trade. This has now been done. Moscow is now halfway or two-thirds of the way along the path of exploiting its Superpower status to achieve a change in the world balance of power. But there are two elements of weakness in the Soviet position vis-à-vis the United States, as since 1945. The Soviet economy, particularly in agriculture, is one weak point. The other is the existence of a second massive enemy in China, something the United States does not confront.”

A German editor pointed to a contradiction between what is necessary and what is possible in America’s Ostpolitik: “On one hand, Henry Kissinger had emphasized that the SALT agreement and other arms control arrangements would have the same destiny as the Kellogg-Briand pact if they were to stand alone and not be embedded in a vast and solemn framework of agreements across the whole field of foreign relations with the Soviet Union. On the other hand, Kissinger believes that it is impossible to come to terms with a revolutionary power. If the policy of détente fails, Europe will be confronted with the problem of energy supplies from the Middle East and even more important the question of whether West Europe can retain some measure of freedom and security in view of the Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe.”

A British scholar saw a possibility of interdependence in the Soviet need for American grain and the American need for Siberian natural gas: “The Soviet grain shortage of 1972 was not typical, but the growth in Soviet yields over recent periods has averaged 2 per cent a year while consumer demand has been rising at 5 or 6 per cent a year. This points to a continuing Soviet need for grain imports. There have been Soviet comments indicating fear that as a result of changes in the Soviet climate, the agricultural belt was creeping southwards.”

The foreign editor of a British magazine commented that the “era of manoeuver” might be prolonged, but the present period of negotiation might be limited in duration: “First, there might be a change in the leadership of the USSR, which is old and hesitant about facing up to major problems. The Kremlin faces a problem of a two-front strategy and has failed to give priority either to the China or to the NATO front. It also faces prolonged and increasingly difficult economic problems but has been, unable to take decisive decisions in this field. The next Soviet government will have to make a choice.

“Secondly, Chinese leadership is also going to change soon. The aging Mao-Chou En-lai leadership has shown great instability despite the dominance of a single system and a single man, Mao. Over seven years, China has gone from Lin Piao and Cultural Revolution to Chou En-lai and rationalism. Another swing of such magnitude in the reverse direction could not be ruled out after Mao’s death.

“Thirdly, Soviet decisions on agriculture, if taken by Brezhnev’s successors, might bring fundamental changes in the system of production and distribution, the only way to resolve the problem. Profound political results might follow.”

A British scholar noted that in Helsinki the nine Common Market countries coordinated their policy in the European Security Conference. “In theory,” he said, “the United States has always disapproved of ‘blocs within the NATO alliance,’ but Washington now is being pragmatic about it. If the West Europeans group together, this could complicate U.S. flexibility and unilateral action. if so, will the U.S. continue to support European unity in foreign policy? How would such unity affect U.S. global policy? These questions need discussion now.”

An American scholar expressed skepticism as to whether trade would bind the Soviet Union to the United States with hoops of gold: “The theory is being expounded that Soviet economic dependence on the West for spare parts, feed grain etc., would influence Soviet policy. But, curiously, while trade is supposed to make adversaries pacific, it makes allies belligerent. The United States has threatened to invoke the Trading with the Enemy Act against two of its allies.

“As for the real enemy, it is more likely that private businessmen in capitalist economies would want to continue to do business regardless of the nation’s foreign policy, while the Soviet Union and its state economy would be more likely to take economic losses to achieve results in foreign policy. In the 18th Century, British companies insured French ships against capture by the British Navy in time of war, On the other hand, if we look at trade between Japan and China, we find that Peking made an effort to create friendly firms in Tokyo to achieve pressure on the Japanese government to change its policy toward China. Moreover, China expanded its trade with Japan in the 1950s, then cut it sharply after 1959, permitted it to grow again later, then during the Cultural Revolution reduced it sharply again.

“The economies of the Communist states are essentially autarchic. They will avoid dependence on any one capitalist power except to fill short-term needs. The Soviet Union is unlikely to become dependent on the United States for grain. There are other grain sources in the world apart from the United States. The Soviet Union does need to import technology in a long-term effort to improve its economy, but it is unlikely that Moscow would put itself at the mercy of the United States for vital imports. There might be a large percentage increase in American trade with the Soviet Union from its recent low levels, but the ultimate volume is likely to remain small.

“Furthermore, economic interdependence does not assure peace, if history is a guide. World War I was fought among the major trading partners. Just before it broke out, Norman Angell in “The Great Illusion” commented that war was impossible because no one could gain from war. He may have been right. But war came anyway.”

A State Department Soviet analyst said: “The Nixon Administration has always seen relations with Russia as an ‘era of manoeuver.’ The phrase ‘era of negotiation’ was an oversimplification used for public consumption. Washington does not assume that the Soviet Union is dedicated to stability. But an attempt is being made to build a Soviet stake in stability, create a Soviet interest in stability. It is part of a grand tactic employing both carrot and stick.

“The United States admittedly sees value in flexibility in its bilateral relationship with the Soviet Union. But Washington remains dedicated to coordinated policies in the NATO Alliance. This is easier said than done. But it must be noted that this is not just a U.S. problem; each ally has the same problem to consider.

“The American belief is that its Ostpolitik serves the interests of Western Europe as well as the United States, but that the machinery of relations with the allies needs to be adjusted to ease difficult problems and friction. As for widespread theories about a new pentagonal power relationship in the world, it is a fact that this view has captured the thinking of some people in Washington. There has been a growing feeling in Washington that, as economic problems come to the fore and some security problems recede, a five-power world is evolving.

“Washington believes that the Soviet operational code includes the imperative to take advantage of opportunities in the international arena. But the Russians are aware of the fact that they are operating from a position of weakness — and not only in economics and in the fact of a China challenge. In strategic arms, the Russians would like to consolidate the fact and image of general parity. But they don’t believe they have won the arms race — as Senator Jackson claims — even if they don’t want to fall behind again. At any rate, this is my personal view; there are other views in Washington which estimate Soviet strength at a higher level.

“SALT is not seen in Washington as simply an arms control or disarmament measure but principally as a political action in a framework of policy. Washington doesn’t see SALT II as urgent now, but there is no intention of leaving it for the next Administration, as some people fear. The interim agreement on offensive weapons will expire in the first year of the next Administration, but this may be more a factor in Soviet calculations than in those of the Nixon Administration. The United States has not lost the strategic arms race, despite critics of the SALT agreements. Rather, the United States may have won an arms race while appearing to lose it. SALT I has left each side with an assured second-strike capability; this is the essential bedrock, even if it is not the only strategic desideratum.

“A tough stand toward the allies is now popular in the United States; we may see more of this on the question of American and European troop levels. On MBFR, Washington sees two policy roles that it serves: the first is the tactical role vis-à-vis the Senate in containing the Mansfield amendment; the second is to really explore the possibility of the kind of reciprocal reductions that still maintain alliance security — without any certainty that such reductions can be negotiated. You may have noted the overwhelming vote of the Democratic Caucus in the Senate last spring to press for substantial reductions in U.S. troops overseas. Senator Mansfield said that of 57 Senators who attended the meeting, fewer than a dozen opposed. In fact, only three Senators opposed the resolution in its final form. As originally proposed, the resolution called for a reduction of two-thirds in the American troops. That aroused some opposition and the language was changed to ‘substantially.’ The danger now is that this question will come up not only in the form of resolutions to register Senate opinion but as amendments attached to money bills that it is difficult for the President to veto.”

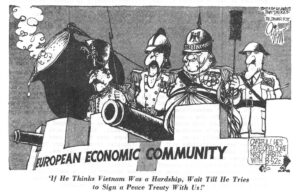

A British Defense Ministry official said that the London view is that it is too early in the second Nixon Administration to form judgments, but there are European concerns about SALT II, MBFR, and the European Security Conference. Europe sees the United States and the Soviet Union locked in negotiations and wonders whether Washington will really extract any concessions. Europe wants to create a European defense identity and carry more of the burden but how can this be reconciled with U.S. objectives?

“The Soviet Union, whether weaker or stronger, seeks the same aims as before: to divide Western Europe from the United States; if possible, to eliminate NATO; and to maintain a defense capability that would enable them to accomplish this. The pressure on the United States to make concessions is greater than that on the Soviet Union. London sees dangers for Europe in SALT II and MBFR that did not exist in SALT I. As Cromwell said: “No man goes further than the man who isn’t clear where he is going.”

“If the United States and West Europe are to maintain their partnership, they have to work out a coordinated position. But this is difficult to do. The nine Common Market countries can operate in the economic and monetary field. But they are a long way from political unity and France is not participating in defense. Coordination cannot be achieved in the NATO Council nor is it possible in bilateral relationships. As a result, Europe may be forced to accept American decisions on the tactics of the negotiations.”

It is clear from all these comments, much as they vary in viewpoint, that the United States and its allies are in mid-stream in reforming their own relationship and an evolving new relationship with Moscow. Both sets of relationships are extraordinarily complex, not to be described adequately by such words as “partnership” “détente.” Both need active management. Neither can safely be left to vegetate for 3 1/2 years.

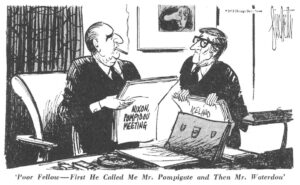

President Nixon is going through the pretense of active management with 10 visits from foreign chiefs of state in three months. He still plans to tour Europe toward the end of the year. But motion is not the same as movement.

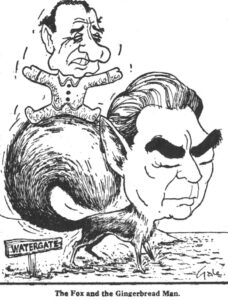

Watergate has neutralized the Presidential power that permitted Henry Kissinger to negotiate with authority in Moscow, Peking, Hanoi, Tokyo, Paris, Bonn and London. Mr. Kissinger now is evidently seeking a substitute power base, with Mr. Nixon’s consent, in the form of a bipartisan foreign policy coalition in the Senate and outside. It is an ambitious project, undoubtedly over-ambitious in the present Washington climate. But seen from West Europe, the Kissinger move offers the first hope that American policy abroad can be put back on course — and even improved. Unlikely as it is that Mr. Kissinger, with all his diplomatic skill, can obtain a broad Congressional mandate for the President, even in foreign policy, his efforts to do so might turn into a new form of ad hoc consultation on individual measures that would permit step-by-step progress in negotiations already engaged and, perhaps, even some new initiatives.

(To Be Continued)

Received in New York on August 8, 1973.

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, the Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.