London, England September 12, 1973

‘I am not dangerous…(In the nuclear age) there is no alternative to conducting relations between our two countries on the basis of peaceful coexistence…We want the further development of our relations to become…an irreversible one…to give these relations maximum stability and to turn the development of friendship and cooperation…into a permanent factor for worldwide peace…mankind has now outgrown the rigid "cold war" armor that it was once forced to wear.’

Leonid Brezhnev in the U.S.

June 18-25, 1973

‘It is time that the U.S. recognized the existence of its own policy toward the East. The policy of this government should be consistent, not one of engagement with the Soviet Union in trade and cultural exchange and confrontation in military matters…. Through the exchanges of visits between President Nixon and Chairman Brezhnev, a new and better climate has been created which allows us to talk about the "cold war" in terms of the past…I believe that we should move in the direction of a 50 percent reduction of our total forces stationed in all overseas territories.’

Senator Mike Mansfield

July 1973

‘Our relations with the United States, just as with the other capitalist states, will remain, in the historical sense, relations of struggle, however successfully the process of normalization and détente may proceed. As L.I. Brezhnev pointed out, "The Communist Party of the Soviet Union has always held, and now holds, that the class struggle between the two systems — the capitalist and the socialist — in the economic and political, and also, of course, the ideological domains, will continue. That is to be expected since the world outlook and the class aims of socialism and capitalism are opposite and irreconcilable." The question is, thus, not whether or not the struggle between the two systems will go on. It is historically inevitable.’

G. Arbatov

Director, Institute of U.S. Studies, Moscow

in Kommunist, Issue No. 3, 1973

‘This period requires great sophistication on the part of the American people.’

Henry Kissinger

June 25, 1973

A visit to Moscow provides vital perspective for a study of U.S.-West European relations in the so-called “Year of Europe.” The profound change that has emerged in Russian policy in the Brezhnev era — and its impact on West Europe’s Security — poses what promises to become the most critical problem confronting the United States and its Atlantic allies in the 1970s.

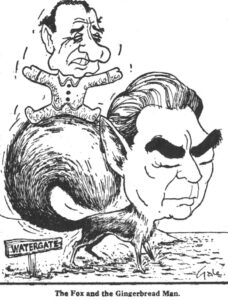

The nature and origins of the Brezhnev policy have about as many interpretations as there are analysts in the diplomatic and foreign press community in the Soviet Union, the visitor finds, not to mention the varied explanations he hears from official, semi-official, non-official and dissident Russians. The crucial question centers on a fundamental ambiguity that to Westerners may seem two-faced, but that Mr. Brezhnev, which ever side of his mouth is speaking, seems to consider a dialectical necessity.

Mr. Brezhnev says he wants “détente,” “peaceful coexistence” and “’long-term cooperation” between the Soviet Union and the West. But, at the same time, the Communist Secretary General insists that the Soviet Union must step up its “ideological struggle” against the West and the overall struggle against capitalism everywhere until the ultimate and inevitable Communist victory.

In contrast with Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, who wants U.S. consistency, the Soviet leaders persist in a double-edged policy. They seek vast investments of Western capital and technology in Siberian development. But, at the same time, they spur Russia’s military buildup; they intensify repression of dissonant voices at home and in Eastern Europe; they encourage anti-Western governments elsewhere, particularly those in the Middle East that supply vital oil to the West; and they continue support for Communist efforts around the world to penetrate, take over or overthrow noncommunist regimes.

Only four weeks after signing an agreement with President Nixon in Moscow in May 1972 on “Basic Principles of Mutual Relations,” which promised that “all countries “would be left free from “outside interference in their internal affairs,” Mr. Brezhnev welcomed Fidel Castro to Moscow with these words: “While pressing for the assertion of the principle of peaceful coexistence, we realize that successes in this important matter in no way signify the possibility of weakening the ideological struggle. On the contrary, we should be prepared for an intensification of this struggle and for it becoming an increasingly more acute form of the struggle between the two social systems. We have no doubt as to the outcome of this struggle, because the truth of history and the objective laws of social development are on our side.”

What is the real meaning of this policy?

At one extreme, there is the interpretation that the Soviet Communists, who have read Clausewitz, see “peaceful coexistence” as the continuation of cold war by other means. It is the interpretation put forward recently by a distinguished panel of British Sovietologists and political scientists in a special report on “The Peacetime Strategy of the Soviet Union” for London’s prestigious Institute for the Study of Conflict. It is also a view the British Government wants no one to overlook. Copies of the 83-page I.S.C. volume, which sells for $7.50, are handed out free of charge to correspondents at the Mutual Force Reduction talks in Vienna who seek out the British position.

The I.S.C. study is predominantly an account of current Soviet and Soviet-encouraged subversion, espionage and political warfare in Western Europe and elsewhere in the noncommunist world. The British Government’s interest in the report makes its conclusions, stated in the introductory sections, worth quoting at some length:

“Fifty-six years after the Revolution, the government of the Soviet Union is a self-perpetuating autocracy, whose principal aim is to maintain itself in power …Its second objective is to expand this power…because the Soviet rulers believe that their system is destined, both dialectically and historically, to triumph over all others.

This secondary objective is pursued in ways which the Soviet leaders do not consider likely to jeopardize the first…. Activities which might lead to nuclear war with the United States are clearly too risky to be practicable for a regime that is not obliged to expand in order to remain in power. The conventional defenses of Western Europe, fortified by an integrated U.S. presence, are also strong enough to make the risks of a conventional invasion of Western Europe greater than any prospective gains….

“A basic change of strategy was therefore required for the period in which the industrial democracies have not collapsed from within and cannot be overthrown by invasion. To meet this situation, the Soviet rulers evolved the policy of a period — theoretically temporary but of indefinite duration — of non-warlike opposition to Western “imperialism termed “peaceful coexistence.” The concept was inherent in Khrushchev’s assertion in 1956…that “there is no fatal inevitability of war”…Khrushchev used the term “peaceful coexistence” at the 21st Party Congress in 1959. But it was not formally spelled out until 1961, when it was…adopted by the 22nd Congress.

“It is worth recalling, however, that the concept, though not the term, was first evolved by Lenin at the end of 1920 or early in 1921, when he realized that revolutions were not, as he had confidently supposed, going to break out in the industrialized countries of Western Europe. He therefore changed the policy of the Comintern to one of united fronts and to a preparatory period in which there would be treaties with the capitalist powers and trade relations and the like from which the Soviet Union could, over a long period, derive advantages…. But the adoption of a form of coexistence in the 1920s did not imply the abandonment of the dogma that armed conflict between the two camps (the Soviet Republic and the “imperialist states”) was inevitable.

“Although the Soviet Communist Party, under Khrushchev, abandoned the dogma of inevitable war, it did not abandon the idea of ‘two camps.’ Indeed the implications of coexistence are often misunderstood in the West to mean that the Soviets are no longer interested in promoting revolution, but are willing to collaborate with the West and other democratic countries to establish a new cooperative peaceful order. The Soviet Union has played its part in encouraging this misconception; but since the term was first popularized by Khrushchev after the death of Stalin, the Soviets have always made it clear that coexistence involves only the exclusion of war as an instrument of policy between advanced states, and that the struggle between communism and Industrial democracy (still called ‘imperialist capitalism’) will continue by all means short of war.”

The British experts point to the “dangers” being inherent in the unchanging nature of Russia’s global policy and its ideological and Messianic character, in Russia’s enormous preponderance in both conventional and nuclear forces and armaments in Europe, in possibly illusory Western expectations of ‘détente’.” But they also note “Important changes in the world situation” including the Soviet-Chinese feud; polycentrism in the Communist world; President Nixon’s visits to Peking and Moscow; West Germany’s treaties with the USSR, Poland and East Germany; the Berlin Agreement; the agreements reached in the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT ); and the new U.S.-Soviet trade agreements and “a growing awareness that the United States needs new sources of energy, of which the Soviet Union has a surplus, while the Soviet Union needs Western technology.” They add:

“The possibility cannot be dismissed that in this new situation, the Soviet leaders may gradually abandon, or at any rate, soften, the policies that have faced the West with agonizing security problems ever since World War II….

“It is fair to say, however, that neither the history of Imperial Russia nor that of the U.S.S.R. encourages optimism on this score, or indeed supports any but a cautious and exploratory response to Moscow’s current overtures.”

Before passing beyond this I.S.C. report, which probably represents the extreme limit of skepticism about Soviet policy among major NATO governments at present, two points are worth noting. If the authors of the report had been responsible for Bonn-Moscow and Washington-Moscow negotiations during the past four years, it is doubtful whether we would now have many of the agreements reached during this period which, they themselves note, have created a “new situation.” Secondly, this new situation leads even these extreme skeptics to favor a response to Moscow’s overtures, though “cautious and exploratory.” And they acknowledge at least “a possibility” that the Soviet leaders may gradually “abandon” the aggressive policies of the past.

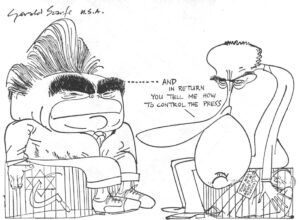

At the other extreme, the most optimistic view the visitor hears expressed by Western diplomats in Moscow goes little further than the Nixon-Kissinger “web of interests” concept of Soviet-American relations and falls well short of Western hopes in earlier periods of “détente.” In earlier periods, there was hope that an evolution could be fostered within the Soviet system. Some even saw the possibility that political liberalization in Moscow and economic planning in the West might lead toward “convergence” of the two systems -a belief expressed only a few years ago by Soviet nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov, who now is himself threatened by the intensified internal repression that is accompanying détente. The Nixon-Kissinger concept is that, without any change in the Soviet system, an interdependence can be created with the West that would lead Moscow to exercise restraint abroad.

A Soviet professor of international relations put it this way: “Just as postwar cooperation and the Common Market have made war unthinkable between France and Germany, which fought three wars in seventy years, so we hope that long-term economic cooperation will make war impossible between the United States and the Soviet Union.”

The trend toward a web of interdependence, it is generally agreed, has had an impact on Soviet policy abroad even before firm American commitments have been made for the large-scale exchanges Moscow seeks of Soviet raw materials for Western capital and technology. The Kremlin failed to react when President Nixon mined Haiphong on the eve of his visit to Moscow last year. The bombing of Cambodia this year failed to delay Brezhnev’s visit to Washington. There is reason to believe, as well, that Henry Kissinger’s negotiation of a Vietnam peace settlement with Hanoi benefited from Soviet good offices. There has been one case of a change in Soviet domestic policy (to the surprise of most Sovietologists), the suspension of the prohibitive exit visa tax on Jewish emigrants to Israel when the reaction in the U.S. Congress, focused by Senator Jackson’s amendment, endangered ratification of the Soviet-American trade agreement in an acceptable form — as it still does.

One American correspondent in Moscow, who is not noted for sympathy to Soviet policy in other respects, believes that Mr. Brezhnev’s acceptance of “an unprecedented level of interdependence with the outside world” is “one of the most fundamental and significant changes in world politics in a generation.”

“This process has gone so far, so quickly,” Robert Kaiser of the Washington Post, has written, “that Brezhnev is already personally committed to it as perhaps the single most important element of his politics. Interdependence — especially with the capitalists in the West and Japan — is supposed to help Brezhnev solve many Soviet domestic problems.”

Soviet interests unquestionably are being served by Moscow’s détente policy — and not only Soviet economic interests. Moscow has been well-paid for its two most important concessions to the West, the Berlin and SALT agreements. In return for the Four Power Agreement on Berlin, which has provided “unimpeded” access and defused that cold war flash point for the first time in a quarter-century, the Soviet Union has received recognition of Europe’s post-World War II frontiers, acceptance of the indefinite division of Germany, East German admission to the United Nations and, in general, stabilization of the Soviet empire in East Europe. In the SALT I agreements, Moscow has achieved acceptance of strategic parity with the United States.

By yielding to Western insistence on mutual force reduction talks for Central Europe, Moscow has received Western acceptance of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, a major objective since 1966. Side benefits from détente have included a growth of neutralism in West Germany, a popular front coalition of socialists and communists in France and a similar trend in Italy, pressure to reduce defense efforts in most NATO countries and increased sentiment in the U.S. Congress for substantial withdrawals of American troops from Europe. At the same time, Soviet military power has grown. Apart from the buildup in strategic weapons, the five additional divisions sent to East Europe in 1968 for the invasion of Czechoslovakia remain in place. The Soviet naval buildup goes on. And Soviet penetration of the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf continues, following the pattern already established in the Middle East and Mediterranean.

Nevertheless, most Western observers in Moscow agree that on balance Soviet policy abroad has undergone a profound and encouraging change. Moscow’s reasons for change, however, are vigorously debated. And that debate is of capital importance, for it concerns essentially the durability of Russia’s détente policy and the risks the West undertakes in cooperating with it. Judgments on these questions will play a crucial role in determining the policy decisions that are shaping up for the United States and its European allies in this “Year of Europe” and the decade to come.

To Be Continued

Received in New York on September 25, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, the Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.