London, England September 21, 1973

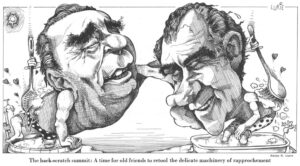

The Russians who have been struggling most valiantly to liberalize the Soviet system feel that they have become the chief victims of the Soviet-American rapprochement. A visiting American finds them bitter and depressed. They ask why Washington has permitted this to happen, as do other Russian intellectuals who are not openly identified with the dissident movement. At a private party in Moscow, with the phonograph turned up, the editor of a prestigious Soviet publication that has served as an outlet for unorthodox thoughts in the past raised his glass and toasted Senator Jackson of Washington as “Russia’s most popular American.” He later explained that the Senator, through his amendment to the bill approving the Soviet-American trade agreement — which was instrumental in getting the Kremlin to suspend the exit visa tax on Jewish emigrants -had demonstrated that the United States could influence domestic Soviet policy if it tried.

Since then, Dr. Sakharov has openly urged the U.S. Congress to support the Jackson amendment, which would make most-favored-nation trading treatment for Russia contingent on freedom of emigration. Warning that U.S.-Soviet “rapprochement without democratization is very dangerous,” the Soviet physicist added: “that would be cultivation and encouragement of closed countries, where everything that happens goes unseen by foreign eyes behind a mask that hides its real face. No one should dream of having such a neighbor, and especially if this neighbor is armed to the teeth.”

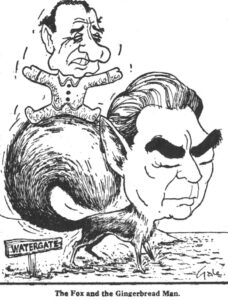

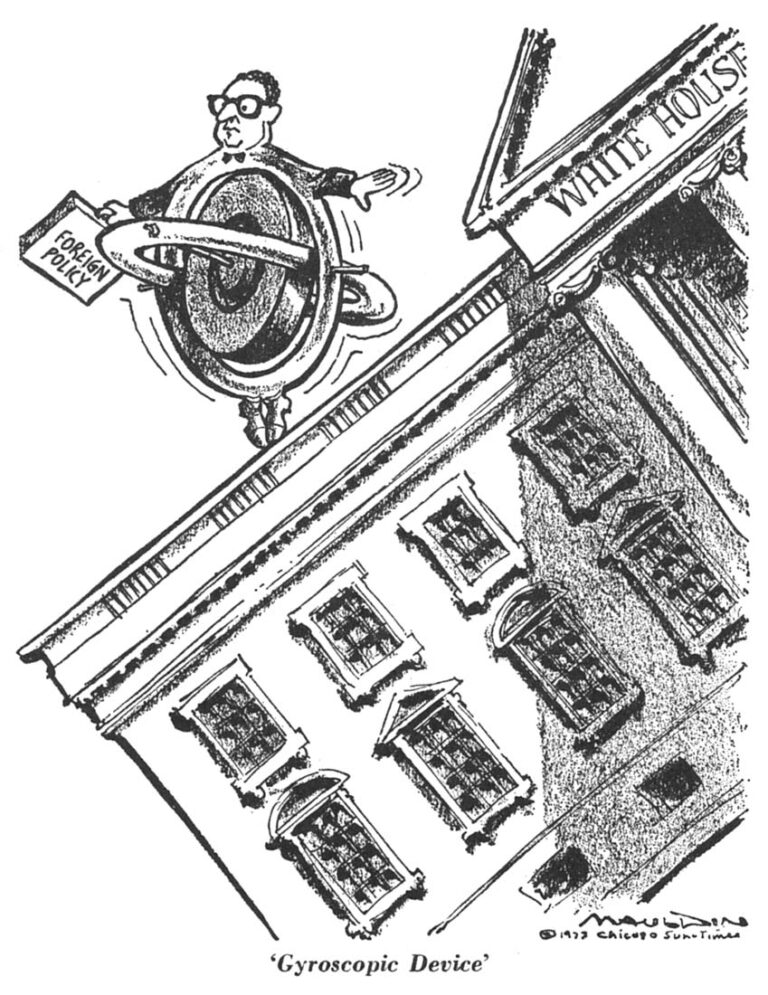

Henry Kissinger, “disappointed” and “dismayed” by the intensification of repression in Russia, nevertheless has argued that “we have as a country to ask ourselves the question of whether it should be the principal goal of American foreign policy to transform the domestic structure of societies with which we deal or whether the principal exercise of our foreign policy should be toward affecting the foreign policy of those societies.”

But the issue is not whether the “principal goal” of American foreign policy should be “to transform the domestic structure” of the Soviet Union. The issue is whether some American effort should be made to impress upon the Kremlin that rapprochement could be hindered if Americans see it accompanied by intensification of repression at a time when détente and a declining external threat should permit an easing of restraints. This clearly is the view of the U.S. Senate, which now has unanimously called upon President Nixon to “use the medium of current negotiations with the Soviet Union as well as informal contacts with Soviet officials in an effort to secure an end to repression of dissent” as well as free emigration.

Expressions of Western concern are not without influence on Soviet policy. That was shown by suspension of the exit visa tax before the Brezhnev visit to Washington and, more recently, by suspension of jamming of most Western broadcasts to Russia and East Europe on the eve of the second stage of the 35-nation Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, where Western and neutral countries have made the freer flow of information one of their major preconditions for recognizing the existing borders in Eastern Europe, as demanded by Moscow.

But there clearly are limits to the leverage the United States can exert on Moscow to alter domestic policies. The ultimate risk, of course, is that the Kremlin majority favoring détente might break up, endangering the SALT agreements, the prospects for mutual force reductions in Central Europe and the modus vivendi with West Germany. But short of this, even the pro-detente majority in the Politburo might prefer to impose economic sacrifices on the country rather than pay too high a price in political liberalization for American economic aid.

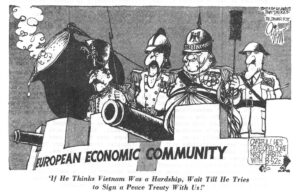

West European diplomats in Moscow, in fact, are skeptical about the whole “web of interests” theory. Doubting that Soviet future behavior can be restricted as Washington hopes — and fearing that too many Western concessions may be made in pursuit of this will-o’-wisp — they also-argue that Russia’s economic needs now are not so desperate as to permit the U.S. to extract major unilateral Soviet concessions. Furthermore, they point out, the United States is not the only source for the grain Moscow henceforth is expected to seek abroad in bad crop years. There are other potential suppliers, such as Canada, Australia and Argentina. As for the technology Russia needs, it is for the most part not the advanced type, in which the United States leads, but the kind that West European and Japanese companies also can provide, particularly turnkey plants for the manufacture of consumer goods.

Some of the vast developmental projects of continental scale now under discussion, such as the Siberian natural gas project, may be beyond the capability of other Western countries. But these are precisely the projects that are least likely to be realized. The huge size of the investment and the long delay before any payout makes private financing of such projects difficult and governmental funds of such dimension are also unlikely to be forthcoming.

Finally, some Soviet analysts believe that liberalization is more likely to come in the Soviet Union as East-West trade and economic cooperation grow, rather than as a result of the kind of ultimatum involved in the Jackson amendment. This is the view of Samuel Pisar, an international lawyer, who is one of America’s chief authorities on East-West trade. He argues that “the enormous agricultural and industrial difficulties” facing the Soviet Union cannot be resolved by importing food and machines from the West.

“That would only lead to a permanent deficit and a mounting dependence and would solve no problems,” Mr. Pisar wrote recently in Le Monde. “To really attack its current difficulties, the U.S.S.R. must experiment with new systems, with new techniques, and rediscover the way to invention, that is, the freedom of thought…the recognition of human freedoms, beginning with freedom of expression. Because it is clear that if writers and artists cannot express themselves, then the inventors cannot invent and the managers cannot manage. There can be no durable economic progress without the confrontation of ideas.”

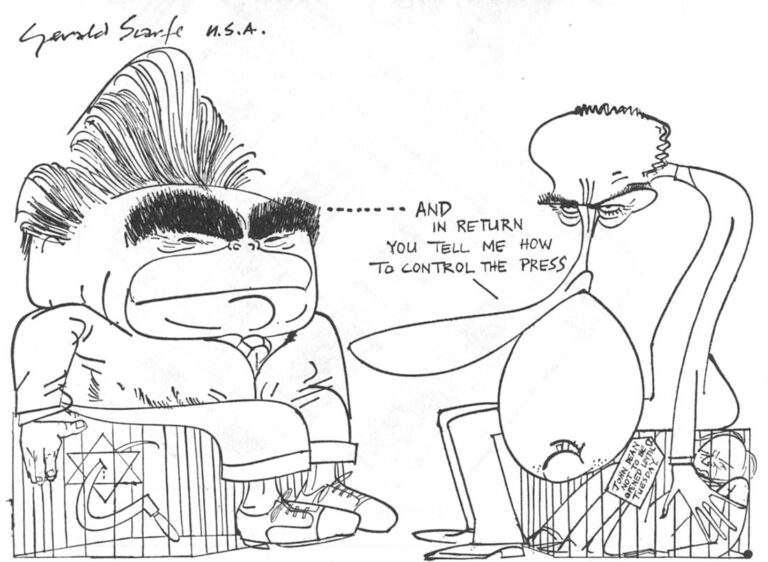

There is much to be said for this view. But, meanwhile, West Europeans point out, Henry Kissinger has excluded internal change in the Soviet Union from Washington’s objectives. West German Chancellor Willy Brandt made an equally mild protest at the treatment of Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn and argued that détente would be a necessity even if Stalin were still in power. West European analysts note that détente seems to force the West to pull its punches about Soviet policy, while the Soviet “ideological struggle” against the West continues. And even if some form of mutual limitation of political warfare could be achieved, would the benefits be equal?

Chancellor Brandt in his first meeting with Brezhnev in August 1970, when the Soviet-German Treaty was signed, made it clear that Parliamentary ratification would be difficult to obtain if the Soviet propaganda campaign against West German “revengists, militarists and Nazis” continued. Brezhnev, a West German diplomat recalled, promised that it would halt, adding that his government’s ability to achieve this could be taken for granted since 99 percent of the country had voted for it in the last election!

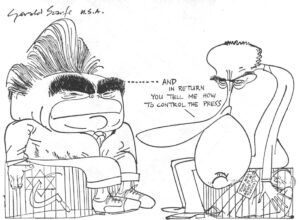

While that last remark aroused wry grins in the German delegation, anti-Bonn propaganda vanished almost overnight from Soviet media. But there was an unspoken quid pro quo. Anti-Soviet propaganda increasingly is discouraged in West German media, particularly those susceptible to governmental influence.

“The upshot,” said a West German journalist recently, “is that the Russians have stopped telling lies about us and we have stopped telling the truth about them.”

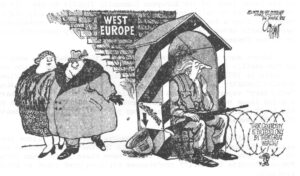

One result has been an increase in neutralist sentiment in West Germany. The JUSOS, the left-wing youth branch of Brandt’s Social Democratic party, have called for the withdrawal of American troops from West Germany on the naive assumption that détente makes Soviet attack impossible and that American troops would impede the West German social revolution they hope to carry out.

Détente, thus, has advanced Soviet policy in the West, while liberalization in the East, so far, is sharply limited by police measures. Two other aspects of the evolving East-West and Soviet-American relationships trouble West Europeans.

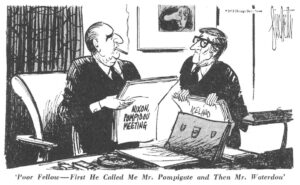

The secrecy and unilateral nature of the Nixon-Kissinger approaches to the Soviet Union have stirred fear that West Europe’s interests will be overlooked or compromised. It is a fear expressed even by some of those who, in the past, have most vigorously rejected the Gaullist thesis that the United States one day would make a deal with Russia over Europe’s head — or behind its back.

Secondly, the Nixon-Brezhnev focus has been on eliminating confrontations that might lead to nuclear war. But, laudable as this aim is, West Europeans see in the new Soviet-American Agreement on Prevention of Nuclear War, signed during the Brezhnev visit to the United States, and in such other East-West negotiations as SALT II and the mutual force reduction talks, a persistent Soviet effort to shift the balance of power in Europe to Moscow’s advantage — and to West Europe’s disadvantage — a change that one day could threaten West Europe’s freedom, if not its survival.

To Be Continued

Received in New York on October 5, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, The Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.