London, England September 24, 1973

In April 1969, long before the NATO allies had reason to be concerned about President Nixon’s later unilateral negotiations with Russia, Henry Kissinger told a White House visitor that the President believed a “profound transformation” of Soviet-American relations could be achieved. Washington’s step-up in the missile race and its much criticized delay in opening the Soviet-American strategic arms limitation talks — linking SALT to progress on other issues such as Vietnam, the Middle East and Berlin — stemmed from a decision by Mr. Nixon to go slow because he wanted to go far, farther paradoxically than some of his critics, and advisers, felt was feasible.

The President’s aim was described as nothing less than assuring that “the danger of nuclear war would be lifted from the world.”

“If the Middle East, Vietnam and Berlin can be eliminated as tension points,” Mr. Kissinger reportedly said, “no other foreseeable Soviet-American divergence would be likely to precipitate a nuclear confrontation.”

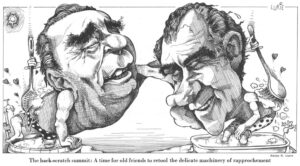

Four years later, on June 22, 1973, with Vietnam and Berlin agreements concluded and an uneasy Mideast cease-fire ending its third year, President Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev, meeting in Washington, solemnly signed an “Agreement on Prevention of Nuclear War.” It might have been expected that Mr. Kissinger would boast that “Mission Impossible” had been completed. But, the Soviet comments were far more joyful than the American.

The agreement pledged Washington and Moscow to “avoid military confrontations,” and to “immediately enter into urgent consultations” and “make every effort” to avert nuclear war if at any time their relations with each other or with other countries “appear to involve the risk of a nuclear conflict.”

Mr. Brezhnev’s spokesman called the accord “one of the most significant agreements in contemporary international relations.” Later, Soviet commentators listed it as first in importance among the score of Soviet-American Summit agreements since May 1972. Mr. Brezhnev himself suggested that the United States and the Soviet Union were bilaterally undertaking a new “special responsibility” for the “destiny of universal peace and for preventing war.” The implication was that the United States had accepted the Soviet Union as a coequal partner in preserving world peace and that Moscow now had achieved parity in crisis management in addition to the nuclear parity to which the U.S. had agreed in SALT.

But there was a quite different tone in the official American comments, Europeans noted. Washington seemed to be trying to play down the importance of the agreement — perhaps in response to hostility by West Europe, Japan and China to the smell of “Superpower Condominium” and to other aspects of the accord.

Admiral Moorer, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was quoted as saying about the agreement: “It does not mean a hell of a lot.” Mr. Kissinger, after going to pains to emphasize that a number of NATO allies had been consulted in advance and that NATO obligations were not affected — suggesting that someone thought they were — gave the impression initially that the agreement was “non-binding” and “not self-enforcing,” an impression which he later tried to explain away, presumably after some Soviet eyebrow-raising.

The President’s security adviser made it clear that the agreement was Moscow’s idea, not Washington’s .At the end of the Moscow Summit in May 1972, Mr. Brezhnev had put it on the agenda for the next year’s discussions. “That was the third time that this agreement on the prevention of nuclear war in a slightly different context was raised,” Mr. Kissinger said, indicating that the United States had turned it down twice before.

What had changed? Why was this Soviet proposal, clearly distasteful to the NATO allies and avoided at least three times, finally accepted?

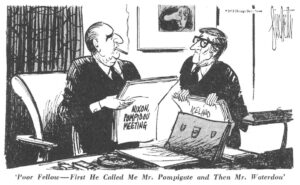

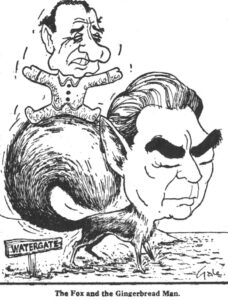

Some European officials believe Mr. Brezhnev took advantage of Watergate and Mr. Nixon’s increased desire for a harmonious Soviet-American Summit in Washington to insist on the agreement that Russia would be consulted if nuclear war threatened “anywhere in the world” — something, Frenchmen noted, that the U.S. had refused to grant to Britain and France when General de Gaulle proposed it repeatedly during the 1958-62 period.

Some American officials have suggested that the accord was an alternative to Soviet proposals for a “no-first-use” of nuclear weapons agreement, which would prevent U.S. use of its nuclear forces to deter or counter a massive attack in Europe by Russia’s far superior conventional forces. Others in the Nixon Administration have justified the agreement as precluding a Soviet attack on China. “It is difficult to conceive a military attack by anybody on the People’s Republic of China that would not endanger international peace and security,” Mr. Kissinger told a press conference questioner on June 25, “and therefore it would be thought…not consistent with our view of this treaty (sic).”

Mr. Kissinger added that this “does not imply that we have any reason to believe that any such (Soviet) attack is contemplated,” a normal disclaimer. But the fact was that concern over the possibility of a Soviet nuclear attack against China had been indicated to the NATO allies for some time, partly perhaps in preparation for signing the Prevention of Nuclear War Agreement, which Mr. Kissinger may have felt could not long be avoided.

On May 9, 1973, the President’s security adviser passed through London briefly on his way home after 25 hours of conversation with Mr. Brezhnev over four days at his Zavidovo dacha northwest of Moscow to prepare the June Nixon-Brezhnev Summit. At a small dinner at 10 Downing Street, Mr. Kissinger reportedly told Prime Minister Heath of an ominous warning. The Soviet leader at one point had stated with emphasis that Moscow could not much longer “remain indifferent” to the mounting Chinese threat.

In the context reported, this was taken by British officials as a reference to discussions broached recently by Soviet officials and scholars with a number of Americans -including the writer — on the implications of China achieving a nuclear “second-strike” capability. The Russians evidently believe that China may be reaching a point at which it could absorb a Soviet preemptive “first-strike” and still retaliate with nuclear-armed missiles against Soviet cities.

Some Western analysts have speculated that the Russians must be weighing whether or not they can permit this point of no return to pass. Similar debates took place within the U.S. Government in the years after Russia’s first explosion of a nuclear device in 1949.

Soviet commentators have vigorously denied reports from Peking, written by columnist Joseph Alsop, that the Chinese had reason to fear a Soviet preemptive attack. But a public, if indirect, threat of this kind was made in September 1969 when Soviet journalist Victor Louis, who is believed to have close ties with the secret police, reported that Soviet generals were debating nuclear retaliation against china in the event of further border clashes.

After the Kissinger-Heath conversation on May 9, British officials recalled that as far back as last November, a member of Mr. Kissinger’s staff had surprised them by evoking the danger of a major Russo-Chinese war. The American official remarked that American strategic studies had concluded that such a conflict would not be in the American interest, particularly if it led to total Chinese defeat and Soviet occupation of North China’s warm water ports. In view of the major Soviet naval expansion underway, he said, such a development could alter the balance of power in the Pacific.

Further light on what some Europeans call the “China rationalization” for the Prevention of Nuclear War Agreement came in late May 1973 with publication of a Nixon Administration leak about a Soviet proposal in 1970 for “joint retaliatory action” against China, if Peking launched a nuclear attack against either Russia or the United States. As reported in the book, “Cold Dawn, the Story of SALT,” by John Newhouse, the Russians informally raised the issue of “provocative attacks by third nuclear powers” early in the SALT talks, then on July 10, 1970 made a formal proposal.

“A stunning glimpse of Moscow’s China phobia was provided,” Newhouse wrote. “On learning of plans for some ‘provocative’ action or attack, the two sides — the United States and the Soviet Union — would take joint steps to prevent it or, if too late, joint retaliatory action to punish the guilty party.

“The Soviets, in effect, were proposing no less than a Superpower alliance against other nuclear powers. Although clearly aimed at China, the proposal risked arousing NATO, whose membership includes two other nuclear powers, Britain and France. The Soviets never would explain exactly what might constitute provocative actions.

“Washington rejected the idea immediately and just as swiftly informed the other NATO governments, lest they hear of it through another channel and conclude that SALT really did foreshadow a great-power axis or condominium.”

Were these the two precursor proposals of a Prevention of Nuclear War Agreement “in a slightly different context” mentioned by Mr. Kissinger on June 25? If so, it is important to note that in 1970, the U.S. reaction was a flat negative, while in 1973, the U.S. negotiated an accord, although in altered form.

Russia’s phobia about China undoubtedly is a reality. But it is so much of a reality that it is unlikely that a momentous Soviet decision to launch a preemptive strike against China’s nuclear installations — a decision that undoubtedly would be based on fear of more dire alternative risks — could be deterred by the June 1973 agreement with the U.S. On the contrary, although Mr. Kissinger has denied it, that agreement might well be used by the Russians to claim that they acquired a free hand to act by consulting or informing the United States shortly beforehand.

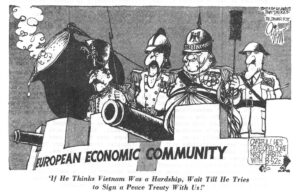

But what concerns the NATO countries is not the value or the lack of value of the pact in deterring a Soviet-Chinese war, but the uses Moscow sees for the Prevention of Nuclear War Agreement elsewhere in the world and, particularly, in Europe. Although Mr. Kissinger asserted that NATO countries were consulted beforehand, weeks after the agreement was signed, West Germany was still seeking reassurance from Washington that the American nuclear guarantee and other NATO obligations had not been weakened.

The question that troubled the West Germans and other NATO countries was not the restrictions accepted by Moscow in the agreement, but those accepted by Washington. Does the agreement, for example, mean that the United States would have to enter into consultations with the Russians before coming to the defence of an ally under attack?

Mr. Kissinger’s response to this question on June 25 was: “The Agreement for the Prevention of Nuclear War, in Article 6, makes clear that allied obligations are unaffected. Secondly, the significance of Article 4 is that in case of situations that might produce the danger of nuclear war in general, consultations have to be undertaken.

“It should, therefore, be seen as a restraint on the diplomacy of both sides…not a guide to action in case those restraints break down and war occurs.”

This statement did not strike Europeans as entirely unambiguous. On July 11, after considerable debate in Bonn, West German Foreign Minister Walter Scheel flew to Washington on a surprise trip, reportedly to raise this as well as other post-Summit issues. Less than a week later, the issue was raised again by West German Defense Minister Georg Leber during a Washington visit that had been scheduled previously. On his return to Bonn on July 19, Mr. Leber told the press that he had obtained satisfaction on the two key questions that reportedly had been troubling members of the West German cabinet.

Mr. Leber said he was assured that the Agreement on the Prevention of Nuclear War would become invalid at the moment of any attack from the East against a NATO member. Secondly, the NATO alliance principle was preserved under which an attack on one member would be treated as an attack on all.

Nevertheless, concern remains. “The nuclear pact of San Clemente raises questions which fundamentally affect the relationship between détente and security and which reach far into the future,” the well-informed Bonn newspaper General-Anzeiger commented after the Leber statement. “In spite of assurances, the doubt exists whether the United States, after the outbreak of a conventional conflict in Europe would not at first take the chance of consultation (with Moscow) before involving itself in a worldwide nuclear conflict. And finally there is the question of the consequences for the European partners of the United States if Washington considers itself as the guarantor-partner of the Soviet Union in Europe. What room remains for the Ostpolitik of the European nations and what are the consequences for their efforts at political and military integration which Moscow would like to thwart?”

Some Americans have tried to reassure Europeans by arguing that the agreement merely codifies existing practice. As early as 1967, at the start of the Egyptian-Israeli six-day war, Moscow immediately opened consultation with Washington on the “hot line.”

But it is one thing for Washington to conduct secret bilateral discussions with Moscow during a Soviet-American military confrontation in the Middle East. It would be quite another matter to deal bilaterally with Moscow during a European crisis. And Mr. Kissinger has indicated that confrontations between NATO and the Warsaw Pact in Central Europe are not excluded from this bilateral consultation agreement. He told newsmen on June 22 that if such an agreement had existed a decade ago, it might have prevented several Berlin crises. Bilateral Soviet-American crisis management during a new Berlin confrontation — or in the event of an East-West German border clash under disputed circumstances -would make a farce of the North Atlantic Alliance.

Article 5 of the agreement permits each side to inform its allies of the “progress and outcome” of the consultations while they are underway. But, contrary to the White House “Fact Sheet” issued on June 22 with the text of the agreement, this does not necessarily mean that “secret bilateral consultations are thereby not involved.”

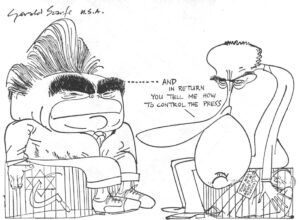

In far less critical circumstances, Mr. Kissinger himself once explained how disruptive of alliance relationships bilateral Soviet-American discussions can be, even if the allies become privy to them at second hand.

“The alliance cannot survive the kind of diplomacy that preceded the abortive summit conference of 1960,” he wrote in 1961. “The separate conferences of the Western heads of state with Khrushchev, one after another, were piously called ‘conversations.’ But heads of state cannot just converse; indeed, summit conferences are urged with the argument that only heads of state are in a position to make binding decisions. Whatever the protestations to the contrary, separate conversations raise the possibility of bilateral arrangements. That such a style of diplomacy inherently creates distrust is shown by the fact that President Eisenhower, to make plain his good faith, found it necessary to tour Europe before meeting the Soviet premier, and that other heads of state visited their colleagues to report on their conversations with Mr. Khrushchev.

“Negotiations with the Soviet Union have become involved in the domestic politics of the allied countries, whose political leaders have found it wise to run on claims of their peculiar ability to bring about peace by restraining bellicose or recalcitrant allies. This has created additional pressures for bilateral negotiations….

“This situation must be ended.”

Imagine what Professor Kissinger, if still at Harvard, would have written about the events of May-June 1973, when Mr. Brezhnev first spent four days conferring with Chancellor Brandt in Bonn, then six in the United States, followed by two days conferring with President Pompidou in France!

Secretary of State Kissinger, as a result, will not be surprised at Europe’s continued concern over the Agreement on Prevention of Nuclear War, which has taken Soviet-American bilateral negotiation to the point of an agreement of “unlimited duration” on bilateral crisis management “anywhere in the world,” including Europe.

The manner in which the agreement was reached maximized the damage to Alliance relationships. According to a West German cabinet minister, only Chancellor Brandt, President Pompidou and Prime Minister Heath among the NATO allies were informed — during the final stages of the negotiation -and they were sworn to secrecy. Mr. Brandt took this injunction literally and refrained from informing his defense or foreign ministers or any other member of his cabinet. While the German Chancellor sent Washington his personal comments on the text, they did not benefit from consultation with or study by his top advisers, who were still protesting three months later — protests directed less against Brandt than against the Nixon-Kissinger team.

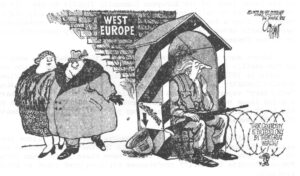

More important, however, than adequate Alliance consultation and even the distasteful hint of “Superpower Condominium” in the nuclear war agreement was its effect in weakening further the declining credibility of the American nuclear guarantee upon which Europe’s security ultimately depends. For the Soviet-American pact comes at a time when President Nixon and Mr. Kissinger himself have been warning Europe of “radically changed strategic conditions” which require Europe to depend much less on American strategic nuclear weapons for its defense.

“The West,” Mr. Kissinger said in April, “no longer holds the nuclear predominance that permitted it in the ’50s and ’60s to rely almost solely on a strategy of massive nuclear retaliation. Because under conditions of nuclear parity such a strategy invites mutual suicide, the Alliance must have other choices.”

What, West Europeans are asking, does this stern warning portend?

Received in New York on October 5, 1973

©1973 Robert Kleiman

Robert Kleiman is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellow on leave from The New York Times. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Kleiman, The Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.