CAIRO — When Salah Jaheen, Egypt’s leading political cartoonist, was visiting the United States in 1964, he was invited to the home of a Jewish family in a small town whose name he has forgotten. “The wife brought me a cartoon from an Egyptian magazine with a Jewish stereotype — a crooked nose. I said that this was a stupid cartoonist who doesn’t know anything.

“For years our cartoonists made a terrible mistake by drawing horrible Israeli characters. There is a joke that when the Egyptian soldiers came back from the front they said1we weren’t fighting Jews because they didn’t have dark beards and horrible noses.”

If one is looking for the image that a country has of itself and its enemies, political cartoons are a good place to start. All the more so in a nation like Egypt where the illiteracy rate approaches 70 per cent and a picture can truly be worth 1000 words.

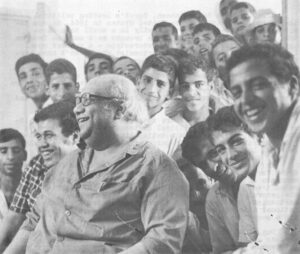

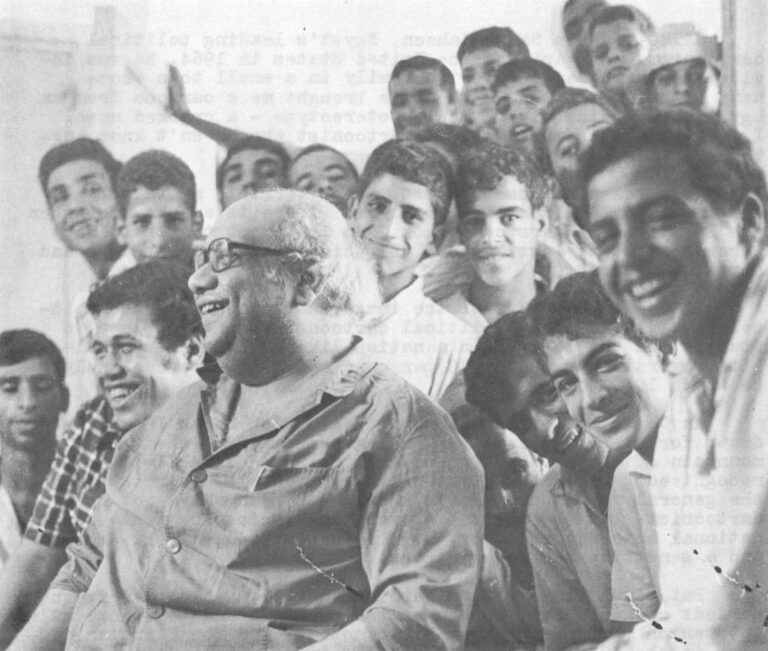

In Cairo, political cartoons begin with Salah Jaheen, who draws for Al Ahram, Egypt’s leading newspaper. Jaheen is a mountain of a man, whose round, multi-chinned, mobile face is recognized by peasants, taxi-drivers, students, and most of the general multitude. He is known as a funnyman — not only a cartoonist, but a writer of clever song lyrics (he wrote Egypt’s national anthem), an actor, film scenarist, puppeteer, dramatist, and a sensitive and revered poet.

But since the Six Days War in June 1967 he has had frequent periods of gloom and despair at the economic and political malaise into which the defeat thrust his country. And the Egyptian success in the 1973 war has not totally lifted his spirits. His brow furrows into a huge crease when he talks of this last war, his top chin burrows down into its neighbor, as he slouches behind a shiny black oversized desk in his office apartment, beneath a framed photo of Gamal Abdel Nasser, his emotional hero, presenting him with an award in the mid 1950’s. He broods, “I didn’t change much after 1973. Maybe I don’t think things have changed that much. I’m not sure they will. I had my euphoria in the socialism of the 1950’s and the early 1960’s. Now other people are having theirs with dreams of capitalism in the 1970’s. But do you really believe the United States and Faisal will let Egypt get strong? Do you really think either one will give us the money?”

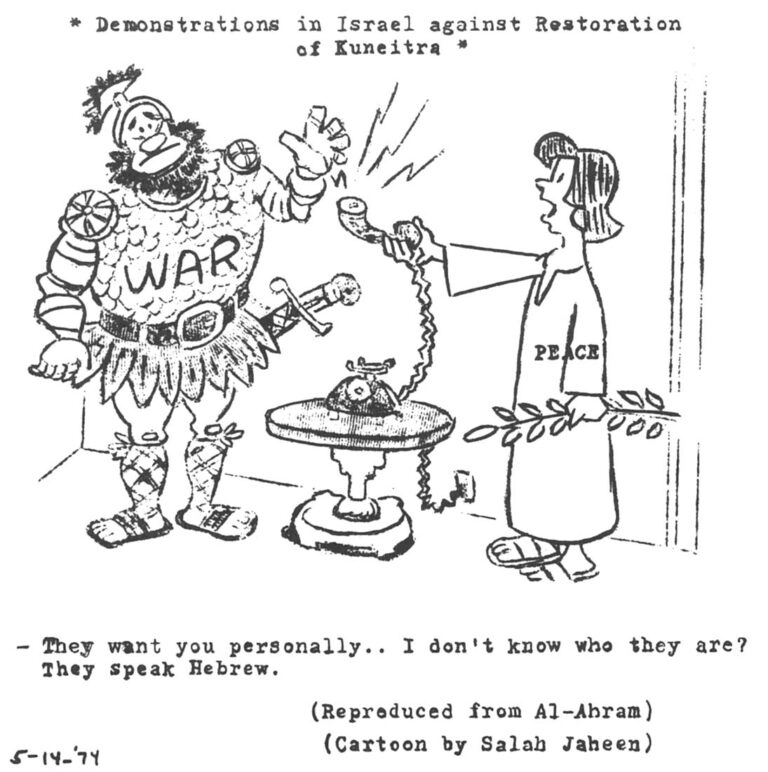

Jaheen’s skepticism shows in his cartoons. They are never vicious. But they show his bitterness towards the Israelis for destroying his country’s economic prospects in war and for displacing the Palestinians. His Israeli figures are warlike and uncompromising, insensitive to Palestinian suffering and indifferent to world peace. At the same time he is critical of his own country, for engaging in a war in 1967 that it was unprepared to fight, for economic disorganization and government corruption. “I made some cartoons of Egypt as her own worst enemy,” he told me. “I had (former Prime Minister) Golda (Meir) say to a friend, ‘Don’t do anything to the Egyptians. They will destroy themselves. ‘”

N.B. Reproductions of Jaheen cartoons in this newsletter are mostly taken from The Cairo Press Review, a daily English translation of the Arabic press.

Most of all, he blames the big powers for foisting their problems and ambitions on the Middle East and distorting the basic Arab-Israeli dispute. When former President Nixon and Secretary of State Kissinger visited the Middle East in the spring of 1974 Jaheen’s cartoons were skeptical of American promises. One drawing showed Nixon and Kissinger in Arab dress on camels and was labeled “Nixon Masquerade Party.” The cartoon was pulled by Al Ahram’s editor as offensive to President Sadat’s pro-American policy.

Jaheen’s drawings reflect sensitive personal roots, which are spread all over Egypt. His grandfather, Ahmat Helmi, the son of an immigrant from the Balkans and an Egyptian peasant girl, ran away from his village to seek an education and taught himself to be a writer. He became a famous nationalist (a Cairo main street is named after him) and wrote for anti-British patriotic papers including one run by the great Egyptian nationalist hero, Mustapha Kamel. Hilmi and Kamel became Jaheen’s childhood heroes, and a portrait of his grandfather wearing a magnificent mustache, hangs on his living room wall. Although Jaheen was the son of urban intellectuals (his mother lived in her own apartment and taught before marriage, almost unheard of at that time), he traveled and lived all over the Egyptian countryside as a child because of his father’s job ad a roving public prosecutor and judge.

Jaheen came of age in the heyday of Egyptian nationalism. He quit legal studies at Cairo University in 1951, and worked on the fringes of art and journalism. For a while he was writing advertisements for soft drinks and reading them in his deep voice over the radio. When the revolution came in 1952, he was working as a layout man for patriotic magazines including one edited by a young man named Anwar Sadat.

During the next few years he began cartooning with the encouragement of a small quiet, but influential newspaper editor named Ahmed Bahaeddine, who is today the confidant of Anwar Sadat and the editor-in-chief of Al Ahram. On the first day of the Suez War in 1956 he met a musician on the street who needed words for a melody he had written. Umm Kalthum, the Arab world’s most popular-woman singer, began to ding the song, and Nasser adopted it as the national anthem. Years later, Jaheen wrote to Nasser and asked him to change the words which spoke of war. “He said no, it must remain as is because of its historical value. I never agreed with him. I added some words speaking of peace and integrity.”

Like most Egyptian leftist intellectuals of his time, Jaheen was a fervent admirer of Nasser, despite his censorship of the press and persecution of the left. In 1959 there was a major campaign against the left and many of Jaheen’s friends were arrested. He started writing subtle criticism of the regime in short poems. “I was very afraid of being arrested and ashamed not to be arrested. I later found out that the intelligence people put my name on the arrest lists five times but Nasser personally crossed it out.” (While he still feels Nasser did much for the poor, Jaheen is more sanguine today about the hero of his youth. “I think I have learned to look at him realistically and separate his accomplishments from his faults. He did many bad things in the name of great ideals.”

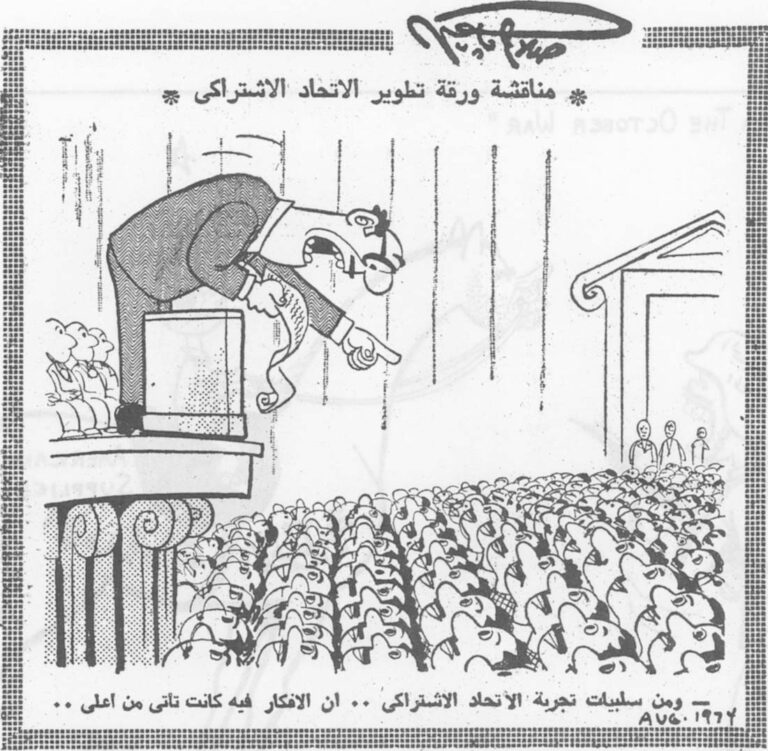

Under Sadat, Jaheen manages to get his anti-establishment licks in fairly frequently. He has repeatedly poked fun at Islamic religious conservatism, especially at the opposition of the Islamic establishment to a proposed law to enhance the personal status of women. Such cartoons have led to attacks by mail and in Friday sermons at the mosques, as well as to occasional threats on his life. Recently, he took a jab at the Arab Socialist Union, the country’s sole, monolithic, political party. His cartoon showed an enormous speaker; sternly lecturing assembled party members from high above, and reminding their mute, identical faces that ASU ideas were supposed to come from below. But two years ago when Jaheen cartooned his support for student riots protesting “no-war, no-peace” he drew Sadat’s ire and the cartoon was axed. And today, he knows the limits, which he cannot pass in criticizing the Americans with his pen.

“It is one of the faults of the Arab Socialist Union that all ideas are coming from the top.”

Since the October War, Jaheen has been skeptical in pen and outlook about the prospects for peace. “Of course, theoretically speaking,” he tells me, “peace with Israel would help Egypt develop. Is this possible? I don’t think so. There are too many who are interested in keeping Egypt from developing. It is not just Israel. It is the big powers who don’t want people like us to get liberated.

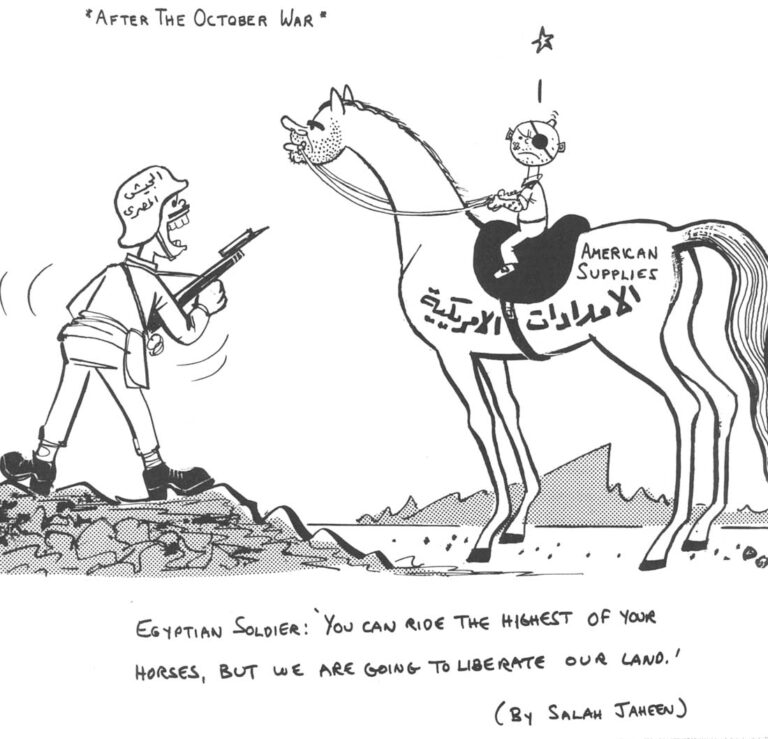

After The October War

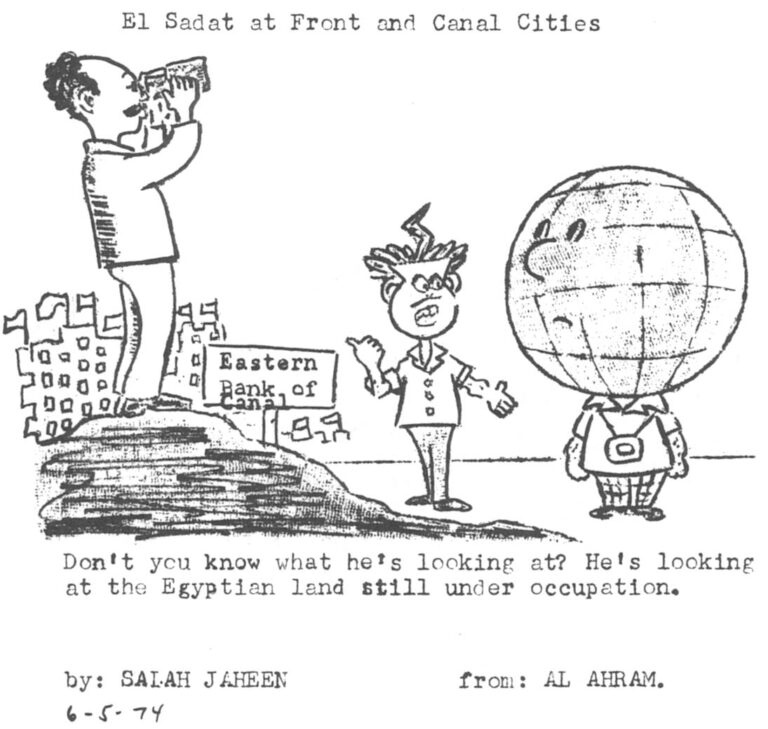

When President Sadat asked him to write a poem for a ceremony for the war wounded he had great difficulty. “If I could have said what I wanted, which wouldn’t have been right for the occasion, maybe I would have said these sacrifices (of the Oct. war) would be worthwhile IF things change here basically. But what have we gotten so far, except a small strip across the Canal? The Israelis have the rest, and except for the ceasefire they would have destroyed the third army.

“Maybe it would have been easier if the Arabs had accepted partition in 1948. I think the idea then was that Palestine should be as it was before — undivided. In 1948, we just didn’t associate the Egyptian Jews we knew and were friends with, with the people over there.”

Jaheen’s ideas about Israel vary from the humorous to the bitter. He grew up knowing Jews from the time that Haim Levy was the only other first grader in his private school class who was not driven to school in a chauffeured car. In his college days, a fellow artist named Yuri Miloslavsky had an apartment in an old Mameluke house where young artists gathered and painted and never talked politics. But Salah, as a leftist, had a special respect for those Jews who had helped found Egypt’s communist party. And when Salah’s father built a retirement house in the Egyptian delta at the edge of the desert, he bought the land from a Mr. Weitzman, who became a friend of the family. The peasants in the village where the house still stands can remember Mr. Weitzman, and they can also tell yon that his son has become a general in the Israeli army.

When Jaheen first began cartooning, he says, he did not distinguish Jews from Zionists. I did not see his cartoons from those days. These days his cartoons are critical of Israelis but in a political and not vulgar or anti — Semitic way. He says he will miss drawing Golda Meir, whom he has portrayed as sexy, witchlike, or just her naturally homely self. “I know her character, but I don’t think I would like to meet her,” he says. “She is an old woman obsessed with something. She will never compromise.” Jaheen once played Mair in a TV satire in which he and Moshe Dayan sang a duet (which he composed) to the tune of the Yiddish classic “Zum galle galle”, pleading with Nixon for more arms. (Jaheen not only learned a few Yiddish melodies from Jews he met in the States, but proudly possesses a tape album of “Fiddler on the Roof” and can often be heard humming “If I were a rich man….”)

Gen. Dayan comes off rather tamely from the Jaheen pen; the cartoonist has not yet found his stride with the rather bland face of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. But while some Egyptian cartoonists still use the stereotype of bearded, hook-nosed, black-robed men for Jews (one recent cartoon showed a group of this vintage representing the Israeli cabinet) Jaheen doesn’t feel this is necessary.

Recently, he has been searching for a cartoon figure to represent the Israeli people, a counterpoint to his little man with the frizzy, stand-up hair who speaks for the Egyptian man-in-the-street. He has pondered over his choice for some time and settled temporarily for a male figure with rumpled casual clothes and a kibbutznik cloth bucket hat (not too unlike the figure used for the same purpose by Israeli cartoonist Dosh, whose work Jaheen has never seen.)

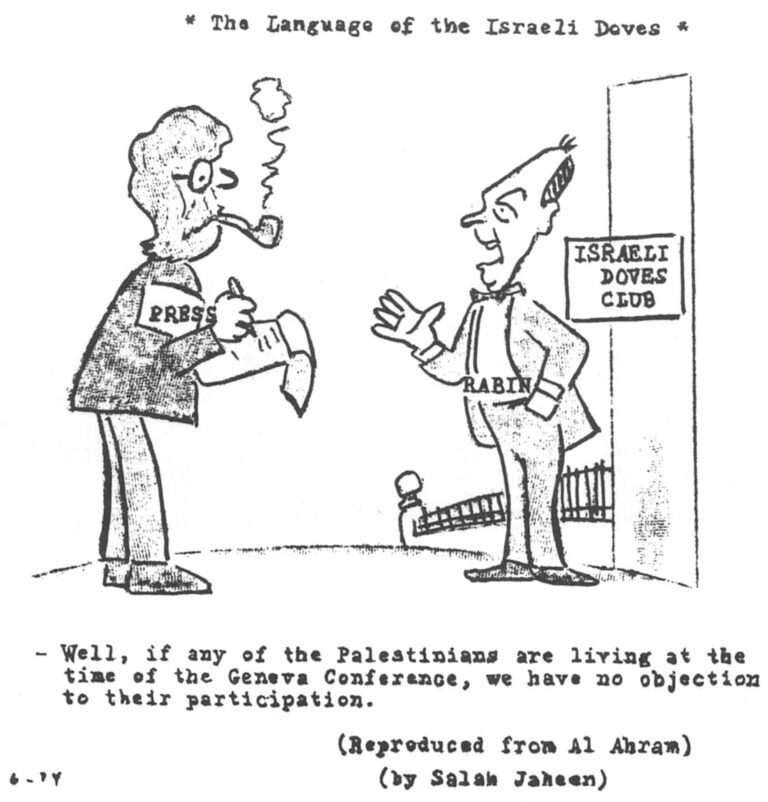

Some of Jaheen’s most bitter anti-Israeli cartoons in recent months have concerned Israeli attacks on Lebanon, including the bombing of Palestinian refugee camps in reprisal for Palestinian guerilla attacks inside Israel. (Jaheen’s wife is a lovely young Palestinian actress.) One drawing shows Israeli Premier Rabin telling a newsman after the bombings, “Well, if any of the Palestinians are living at the time of the Geneva Conference, we have no objections to their participation.” Another cartoon, responding to former Prime Minister Meir’s comment that there was no need for a Palestinian homeland, has a BBC interviewer asking a smug-faced Mrs. Meir, “And the Arabs, generally speaking, Mrs. Meir, do you think there is any need for their existence on the globe?” Another, printed in March 1974, shows the Egyptian common man and the World staring at a Palestinian woman labeled ‘Problem of Palestine’, who casts an enormous shadow over a wall labeled ‘Middle East Crisis.’

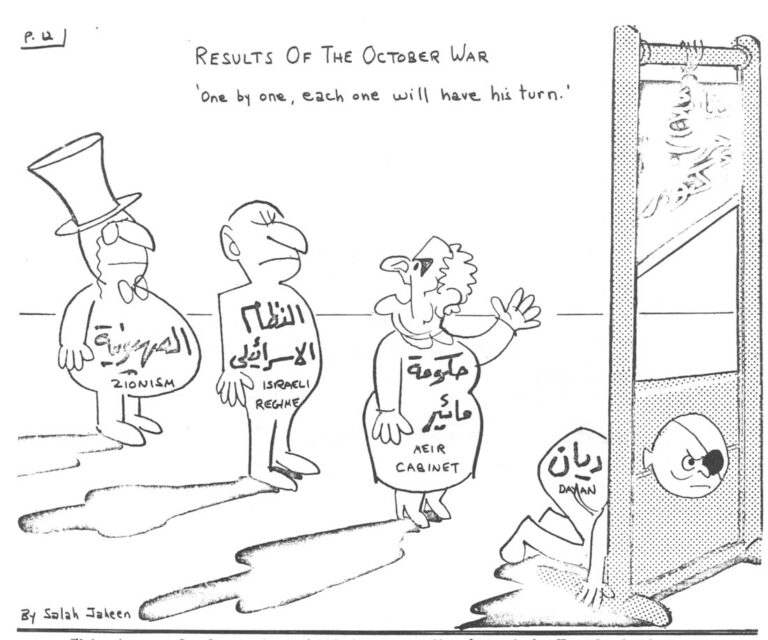

One Jaheen cartoon recently drew the ire of an American Zionist publication, which labeled it an example of recalcitrant Egyptian attitudes. Published in April 1974, it shows Moshe Dayan with his head in a guillotine. Behind him in line, stand Mrs. Meir, labeled ‘Meir Cabinet,’ a nondescript figure labeled ‘Israeli Regime’, and a bespectacled high-hatted plutocrat labeled ‘Zionism.’ The cartoon tag line reads, “Results of the October War, One by one, everyone will have his turn.”

“No, this cartoon does-not mean I want to see Israel destroyed,” Jaheen said somewhat defensively, when I asked him about it. “This is how I really feel. These four symbols stand for the old order in Israel, and all of them will have to go if there are to be new forces in Israel which are really ready to make peace.”

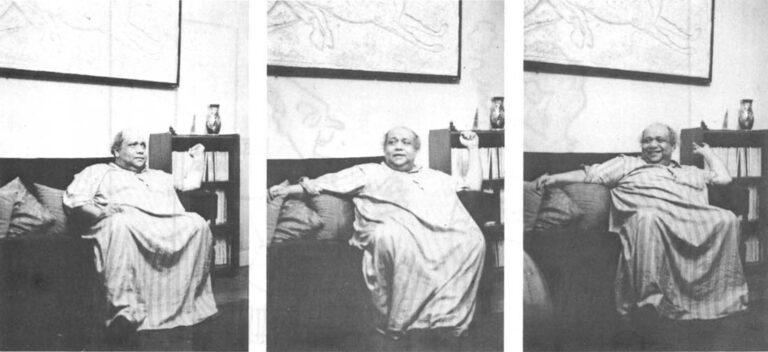

One afternoon, Jaheen settles down behind his giant desk, relaxing in his gelabyia, the striped peasant dress often worn by urban Egyptians at siesta time, and talks at length about his personal feelings on Israel. His hands play with the clutter on his desk, the inks and pens and volume of French poetry and musical jottings he has been composing for a movie score on the elaborately carved upright piano next to his desk. His infinitely mobile face, reminiscent of Zero Mostel in a nightgown, rolls in and out of frowns and deeply thoughtful molds.

“If it were only the Israelis — without outside powers — we would have fought to a conclusion by now which would be a reality. By now they would have returned to their real geographical and political size that of a small country in a large region. They are few and we are ignorant. The only way Israel can survive is by having its natural size. Maybe this means a national homeland existing within Palestine, or maybe a partition like the United Nations voted in 1947. A democratic, secular state like the Palestinians want? Not likely in our generation.

“Israeli intellectuals must be suffering much because they know they are taking other people’s homes, but they think they have to do it in order to survive. It must be torture to them. But ordinary Israelis must be very conceited. They are comfortable with false ideas in their heads about what they are and where they are. The Jews were feeling inferior so they founded Israel so there would be no difference between them and others, and now the Israelis say they are better than other people.

“I am angry about what the Israelis did. But I am sure that I can be friends with many Israelis — more than with some Egyptians. We have received the same culture — with a European flavor — and the same taste. Both of us are different from the majority in the Middle East, but my interests are those of my people and theirs are against my people. A wiser Israeli can be like me and see the interests of my country.

“What do I think the Israelis should do? Any Israeli government which said ‘we are willing to give back the land of 1967, we have suffered from the Nazis and will not be like them,’ would be adored by the Arabs.

“This Israeli government must be thrown out. A new one should tell the Arabs ‘We can’t give up Israel itself, but we condemn what went before and we are ready to be good neighbors.’ Of course, some Arab extremists would say they were bluffing. But the majority, the powerful ones, would accept it and hush the others.

“All we want is to keep war away so we can develop, until there is no technological vacuum between us and the West. Israelis come from the West to fill that vacuum in our area and to benefit from that. If we dealt with the question in a civilized way, maybe they could help us fill the vacuum. IF the wounds are healed, maybe we could accept.

“We can say ‘we don’t want to throw you into, the sea.’ The UN and the major powers can guarantee this. But we don’t want to give them any land from before June 1967. Why should we?

This is our land, as important to us as the desert in Nevada is to you. And if you want the Sinai demilitarized then you do the same to the Negev. Why do people think that only Israel is in need of protection?

“Jewish immigration to Israel (anathema to most Arabs because they think it means expansion) must be dealt with in a rather cunning way. If we decide that this an area where the Jews can live, then the Israelis must agree that even if they bring all the Jews of the world here they can only have a certain piece of land, and expanding means war.

“For the time being it is too soon to be friends because there are still wounds, but in the future they can send folkloric troupes here to dance and we will discover they are human and vice versa and we can play ping pong….

“I an saying all these dreams and I am sure that there are unseen forces that will emerge when things look good and burn a synagogue somewhere or do something that will give someone an excuse to destroy the whole thing….”

Received in New York on October 11, 1974.

©1974 Trudy Rubin

Trudy Rubin is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Ms. Rubin, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.