On the eve of independence Mozambique faces almost overwhelming domestic problems: underdeveloped agricultural system, a shortage of schools and health facilities due to the mass exodus of 103,000 Portuguese, a $950 million external debt, and an acute shortage of foreign exchange.

Which task gets top priority? And how fast can the new government overcome these problems?

Robin Wright recently became the first foreign journalist to travel with tits Prime Minister and several members of the cabinet as they toured the country and revealed the answers to these questions. What follows is an account of the type of meetings held throughout the four-day tour.

Xai Xai, Mozambique

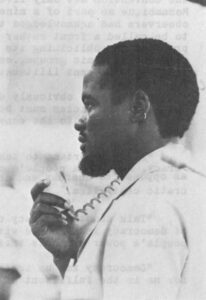

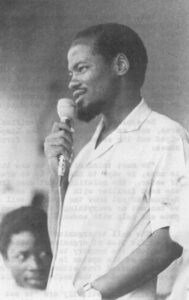

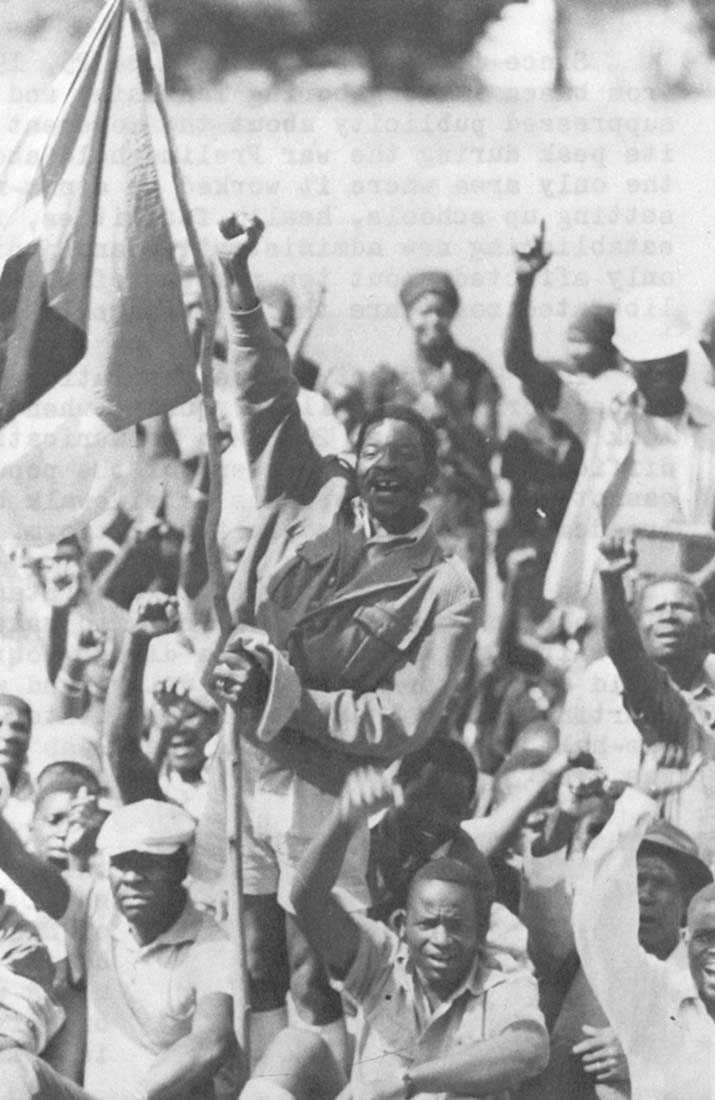

The crowd, 11,000 strong, had been waiting, standing, for almost three hours, many having walked over 20 miles to hear what the new leaders of Mozambique had to say. As Prime Minister Joaquin Chissano reached the open platform it started to pour, but no one moved.

“Who has the power?” the energetic figure called to the crowd, ignoring the rain.

“The people,” the crowd called back, smiles breaking out on many faces.

“Who?” he asked again, also smiling.

“The people,” they roared back louder.

In a sudden serious tone, he surprised them, asking: “Do you say that just because now you have a black Prime Minister?”

Before giving the crowd a chance to answer he continued: “Having freedom does not mean the struggle is over, that the people really have the power.”

“We have a whole system to change and it will take the people, all the people, both black and white people, to do all the work we have ahead of us.”

Gently but candidly he appraised the future: “We have many problems. People are starving in the North. Some people have no water. Others have been flooded out of their homes and lost their crops. But we knew we would find Mozambique in the mess it is now in. That is why we began the fight for independence eleven years ago. We wanted to change the inequality and exploitation and rebuild the nation.”

“But freedom means more than a new flag. It means more than black faces in government. The hardest part of the struggle begins now. And it will take more than songs and poems and slogans.”

For two and one-half hours the soft-spoken but charismatic figure held the crowd, all standing in the cool damp night air, as he assessed the future of this massive southeast African country. The only breaks were pauses to hear from the people about their problems and concerns. With each issue put forward by the crowd, “Comrade” Chissano easily wove the problem back into the message he had been relaying from the start.

“What about unequal distribution,” an older man shouted from the back. The Prime Minister responded:

“Before there is equal distribution there must be production,” (as there currently is a chronic shortage of both food and foreign exchange in Mozambique). “To do that people must be organized. Equal distribution also means there must be concern about more than the immediate locale or one tribe. Equal distribution means de-tribalization, unity, awareness of the needs of the entire country.”

“Discrimination,” a woman called out next.

“It is not color that exploits and oppresses people, it is a system,” Chissano declared in a firm tone.

“Color alone does not divide. It is ideas, not color, that counts, and anyone who has the right ideas, who wants to work is welcome to stay. Frelimo fought to establish equality, so we will not refuse equality to those who refused it to us. We need everyone for the work ahead of us.”

As the crowd continued to call out their problems, the real concerns that had drawn most of them to this rally — although no one would ever mention them specifically — were slowly getting answers. Those questions: What is a peace-time Frelimo? And how will it change their lives?

Although Mozambicans are well acquainted with the movement’s reputation and the names of its assassinated founder Eduardo Mondlane and current President Samora Machel, they have until recently known little about the specific structure of the Front, its programs, or its plans for the future.

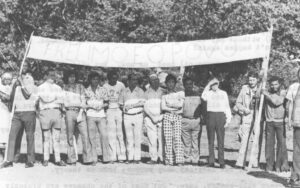

Since it was founded on June 25, 1962, Frelimo has operated from bases in neighboring Tanzania, and the Portuguese government suppressed publicity about the movement as much as possible. At its peak during the war Frelimo held about one-third of the land, the only area where it worked in a non-military capacity by setting up schools, health facilities, farm cooperatives, and establishing new administrative and judicial systems. But this only affected about ten percent of the population, since the liberated zones are the most sparsely populated areas.

Thus, 90 percent of the population knew Frelimo mainly as “liberators,” as a military unit, when the transitional government took over September 20. And communication since then has been difficult because 80 percent of the population is illiterate and cannot read the newspapers or sidewalk billboards that now clearly broadcast Frelimo’s socialist platform.

So it is not difficult to understand the motivation and patience of those who had set out at noon to make the 4 p.m. rally, who had waited right through the dinner hour, standing in the packed field during the three-hour delay, and who stood spellbound, despite spurting showers, as the Prime Minister spoke for another two and one-half hours, all knowing there was a long trek home after it was over.

“I’ve waited all my life for this,” explained an old man, withered shell built-up by the shoulder pads of his second-hand suit jacket. “Three hours, ppsscht, it is nothing. I would wait many more.” He smiled broadly. “I want to know what Frelimo is going to do for us.”

A mother standing next to him, baby tied to her back, added: “This is my future. I want to hear about it.”

The old man and the young mother may have been somewhat surprised by what they subsequently heard. As Mozambicans are learning from similar tours by officials throughout the country, Frelimo is not promising to do anything for individual Mozambicans. But it is promising to allow people to do something for themselves. As the Prime Minister explained to the crowd:

“The colonialists took initiative away from the people. We had no voice in what we grew, how much we grew, or what happened to our produce. We want to give the initiative back to the people.” It was a popular message and the crowd cheered.

The message has a practical as well as ideological motive. Frelimo has neither the manpower nor the desire to send in groups of outsiders to run each village and city, thus simply replacing the Portuguese with Mozambican.

The message has a practical as well as ideological motive. Frelimo has neither the manpower nor the desire to send in groups of outsiders to run each village and city, thus simply replacing the Portuguese with Mozambican.

First of all, the nation currently faces a chronic shortage of skilled personnel, mainly due to the sane exodus of Portuguese, who dominated the education system and thus provided the vast majority of skilled and professional labor.

As the situation deteriorated in the last year of the war many fled, mainly to Portugal and South Africa. The white population of just over 200,000 has been halved since January, 1973. The biggest flight came after September, 1974, when white extremists seized a Lourenco Marques radio station in an abortive bid to prevent Frelimo from coming to power. Fearing a backlash, more than 52,000 have since left. Most had skills that are irreplaceable. So even if Frelimo wanted to simply plug in Mozambicans to the Portuguese system, it could not as there are not enough trained to take over.

But more fundamentally, Frelimo has always advocated that in principle the masses should be involved in government. Throughout the war the movement promised to radically alter the system to allow greater self-reliance once it took over, As Frelimo President Samora Machel explained in his book, Mozambique: Sowing the Seeds of Revolution: “Releasing the masses’ sense of creative initiative is one of the chief purposes of our struggle…. We are trying to make people understand that everything that is done or undertaken depends upon each man himself.”

But, as the new government has acknowledged, Frelimo can only provide the structure for a new system. Beyond that “people must take the initiative.” As Machel added: “Our life and our discipline can be based only on conscious and voluntary involvement.”

Promoting participation in the new government — “spreading the revolution” — was thus one of the primary reasons for this tour by Frelimo officials. As the Prime Minister repeatedly told the crowd at Xai Xai (formerly known as Joao Belo): “Freedom by itself does not produce, does not solve our problems. We must not just sing unity, we must apply it through organization.”

He applied the message specifically to the problems of the area, such as flooding from the Limpopo River that in March wiped out the season’s crops and forced 350,000 to flee their homes:

“We must think of ways to use this water for times when there is none, or ways to channel it to areas where there is a shortage of water. The solutions must come from the people, those who are the most familiar with the area and its needs. We in Lourenco Marques do not know the area as well as you do. And besides, we cannot do everything. If you want the power you must participate and help with answers and programs to solve this water problem.”

The call to organize is not just abstract talk. Frelimo has a specific plan of organization that it is currently installing throughout the country to provide a means for participation. At the core of the system is the circle or cell, a small group pf people gathered from either work or residential areas. A secretariat elected by the members administers the unit.

Cells theoretically are “to set in motion the masses’ creative ability.” Specifically, the most immediate purpose of the cells is to implement two programs to politicize and educate the masses.

“Dynamization,” a political “consciousness-raising” program, is the chief concern, for it is the means through which Frelimo hopes to explain its policies and prepare people for their new responsibilities. “Alphabetization” is a dual education and work program designed to lower Mozambique’s 80 percent illiteracy rate and organize cooperatives for farming.

Basically, cells are to promote the “collective spirit” sad to replace the tribal unit as the source of local authority. Previously both production and administration — except in the few urban areas — have been tied to the country’s nine main tribes, which were easily controlled by the colonial government. Now village administration will be reorganized into elected people’s committees and agriculture reorganized so that producers work in cooperatives under the direction of the local party.

The elimination of tribalism and the switch to a people’s democracy, is a radical one and the Frelimo leadership is trying hard to make it a smooth and fast one — again for both ideological and practical reasons.

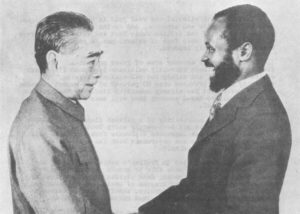

Currently Mozambique is economically reliant on South Africa and Rhodesian use of its ports and railways, and South African employment of Mozambican mine workers. Through these ties South Africa provided about 75 percent of Mozambique’s foreign exchange.

The new government is determined to become economically independent, and agriculture is one of the chief means to this goal. Although agriculture has provided 80 percent of Mozambique’s exports, the system is drastically underdeveloped. Only 17 percent of the territory’s fertile land is cultivated, and mainly for subsistence farming. Through the encouragement of new cooperatives and the “collective spirit” Frelimo hopes to spur productions, provide badly needed new revenue to pay off the country’s exorbitant $950 million external debt, and build a new means to economic self-reliance.

The self-administration of the cells however, does not mean there will be no centralized administration. Quite the contrary. In a speech the Prime Minister gave in Mocuba in February he clearly defined the concept of “democracy” being installed in Mozambique:

“It is important to take into account that, when we say democracy, we mean a people’s democracy under the discipline of Frelimo, as opposed to anarchy and ideological liberalism. We talk of democratic centralism. Talk about democracy can compromise our policy. In the name of democracy, individuals without our objective of establishing People’s Power can make their ideas prevail.

“Therefore, we must be very careful when talking about democracy. When putting that idea into practice we must pay attention that democracy for us is the fulfillment of national objectives.”

The transfer of “power to the people” is thus a gradual process, not happening overnight on June 25.

In explaining the current stage of “the struggle” to the Xai Xai audience the Prime Minister said Frelimo is currently “consolidating freedom and independence through organization:”

“We will have to work hard to achieve real independence. The most important steps to real freedom are organization and unity, so we can produce for the future and fight any remnants of the past. You control the future,” he stressed, “because you control the pace at which we organize and unite to begin this work.”

Eleven thousand people had come to hear how Frelimo was giving them independence and equality now that the struggle against 500 years of Portuguese colonialism is over. But as the crowd learned, the struggle is just beginning. The future of Mozambique will move only as fast as the people are “revolutionized” to follow the path Frelimo has outlined for them.

Received in New York on May 12, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.