Independence for a country like Mozambique, which was under colonial rule for almost 500 years, is not just a political event. Freedom also “liberates the soul and the spirit of the people,” as one Mozambican put it.

Those who best express this new spirit are usually the artists and writers, as Robin Wright discovered during conversations with several artists in Lourenco Marques. Wright has been investigating the impact of independence in Mozambique on the human level as well as the political situation.

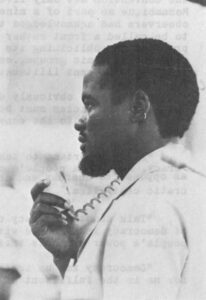

What follows is the story of one young man, his experiences during the colonial period and the difference in his work since his southeast African country moved toward independence.

Lourenco Marques, Mozambique

Fernando Sumbana has no easel or palate. He has never had an art teacher or professional guidance since his school did not offer even finger painting. He has seen but one piece of art from outside his country — a copy of a Picasso; Rembrandt, Vermeer, El Greco, Monet are but foreign names to him. Canvas is unavailable and brushes are scarce.

Yet three years ago the sweet-faced young Mozambican student decided he wanted to try to paint. “Pictures were forming in my head,” he says in halting, heavily-accented English. “Things I looked at had messages in them.”

So he set out to obtain equipment to see if he could make real the images in his head. The beginning was almost the end. His gentle smile broadens and eyes twinkle as he tells the story.

“The oils were thick and ugly at first. I was frustrated. I did not know what was wrong — so I talked to an artist here. He said I shouldn’t paint because I don’t understand the medium. He said I a foolish man. But he told me about thinner,” he lifted the clear little bottle as if it were a prize.

“Thinner made the oils smooth and I could work again,” he grinned shyly. Since then the 20-year-old artist, a member of Mozambique’s southern Changane tribe, has worked in his free hours from studies at Lourenco Marques’ Commerical Institute to bring together the oils and the images.

The results, in brilliant colors and bold strokes, have already made him one of the country’s most promising artists. The new government in this southeast African country took most of Sumbana’s paintings after his first one-man show for display in government offices and city centers. One picture is being used as print for cloth. And people throughout the city talk about his work.

Thinner did not bring all the answers, however. Sumbana originally could afford only five colors — black, white, blue, red, and yellow — so he had to learn how to mix colors, especially for the sensuous brown figures that dominate his works. He points to his “palate” a small square disintegrating styrofoam sheet once used for packaging, to show his progress. It is a rainbow of richness, almost a picture in itself.

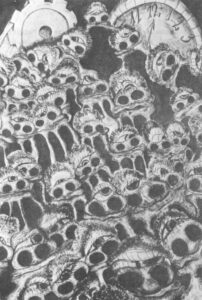

The subjects of his paintings also provided problems. “I see misery in the world and I try to paint it. I don’t know why. I can’t draw flowers or people playing,” he explains. His highly symbolic pictures, distorted, grotesquely haunting and vivid, portray the desperation of poverty, the restrictions on people living under colonial rule, the horror and ugliness of fear.

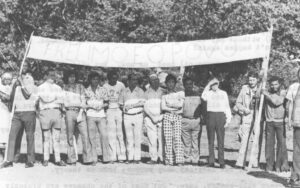

The subjects were controversial and dangerous to display during his first two years as an artist, when the Portuguese were still colonial administrators of Mozambique. It was a period of “added tension” because of the guerrilla war in the northern third of the country between Portuguese troops and the “liberation army” of Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique).

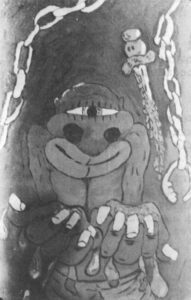

His first work, for example, depicted the evils and oppression of colonialism. A single black man, “the blood of the people” oozing through his oversized, outstretched hands, glares from a massive single eye at the viewer. Chains, cuffs and knives — the literal and symbolic consequences of oppression — angle ominously in the dark background.

His first work, for example, depicted the evils and oppression of colonialism. A single black man, “the blood of the people” oozing through his oversized, outstretched hands, glares from a massive single eye at the viewer. Chains, cuffs and knives — the literal and symbolic consequences of oppression — angle ominously in the dark background.

“I could not tell the real meaning. I was afraid the government would arrest me,” he says, in one of the few moments of seriousness. “So I said it was about the evils of thieving and murder.”

Since the April, 1974 coup in Lisbon that eventually led to an agreement for independence in Mozambique, Sumbana has become more outspoken in his subject matter. There is also a slight shift in emphasis. Previously centered on the misery and problems of the world, some of his recent works offer hope, reflecting more specifically some of the solutions for Mozambique offered by the new Frelimo government, for which Sumbana works as a volunteer in his off-school hours.

For example, Frelimo is planning to expand the country’s small agricultural base by developing collective farms throughout the fertile country. In severe economic trouble, Mozambique must provide employment and new products for export to break from its economic dependence on South Africa, Rhodesia and Portugal. The new government believes the development of agriculture and small related industries is the first major step on that path.

Sumbana’s recent work portrays this goal with simple poignancy. One oil shows a Mozambique family looking over an uncultivated field — into the future — at a glaring red sun, “the sun of revolution,” Sumbana says. A dull gray gear lying in the corner symbolized development.

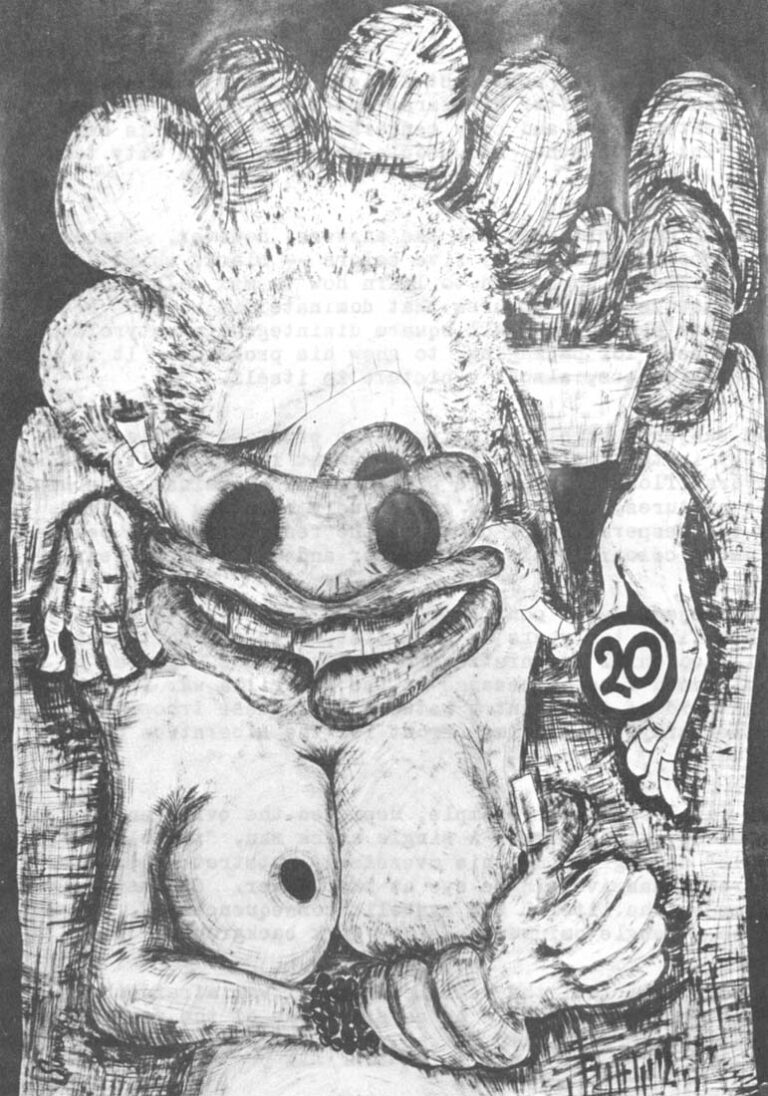

Another dealing specifically with Mozambique shows a bulbously exaggerated pregnant woman preparing gifts and toys for her unborn child. Her expression is painful, but the joy of expectancy shows through too. “We are like the pregnant woman,” Sumbana explains. “We also went through a nine-month transition period (literally, the transition government of joint Frelimo-Portuguese forces ruled from Sept. 1974 until June 1975) of both pain and joy. She is in transition, ready to born a new life, and we are also bearing new life with our independence.”

The symbolism of these works is straightforward, not with the sophisticated subtlety found in his early works of broader themes. In a soft voice, frequently interrupted to check a word in his Portuguese-English dictionary, he explains the earlier oil or ink drawings:

The picture of a prostitute, distorted and grotesque in shape and the faceless crowd of men surrounding her huge head and full breasts, which appear to hang over the picture into the viewer’s lap; her lust for money and the moment rather than meaning; the destructiveness of her “pleasurable talent.”

The pure and passionate love of a poor mother for her growing young child, who stands sucking milk from his mother’s breast, the only gift she can give him.

The material obsession of the western world, symbolized by bulging buildings and bulging people, so full yet so empty.

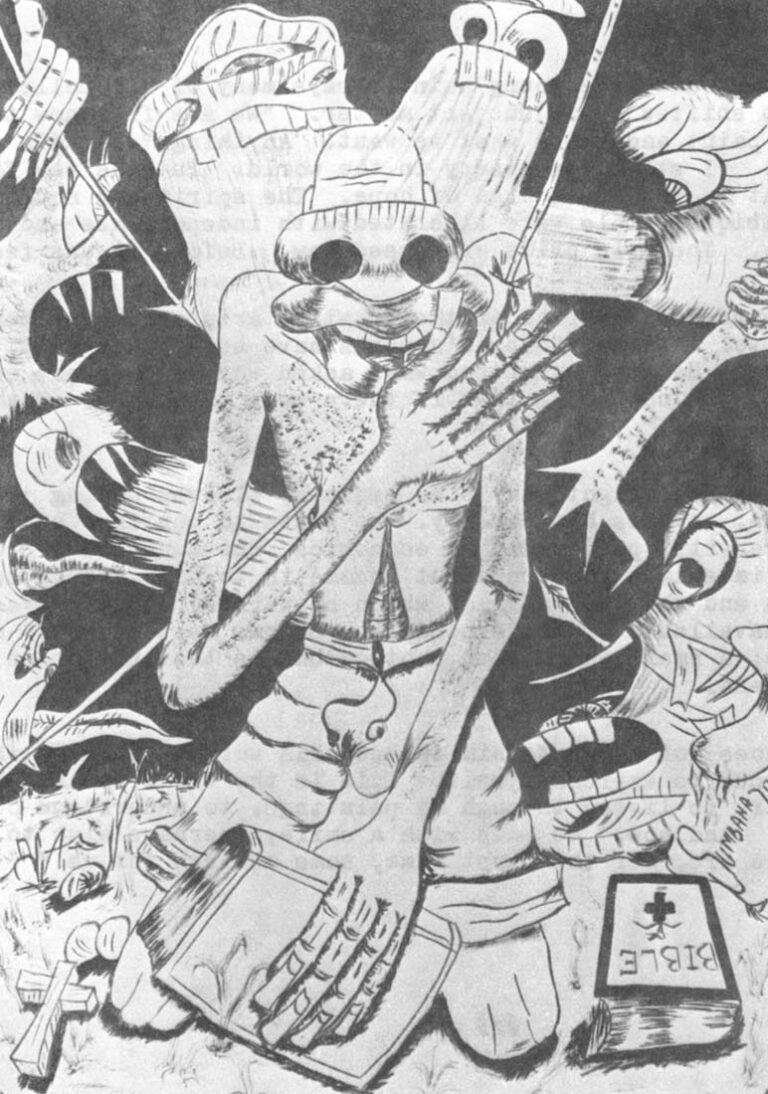

The dependency on religion — the first means of colonizing and “subduing” the African continent by a man who waits for the floating spirits in the background of his haunting, desperate face to do things for him, rather than moving to help himself.

Sumbana speaks unhesitatingly and almost eloquently about his works in a way that surprises his English teacher at the Institute — a white Portuguese woman — who claims he never speaks in class. Later he indirectly offers an explanation.

“It was hard to express ourselves when the Portuguese were here, for fear of arrest or detention. There was no freedom to speak about our problems or our poverty. To be for Frelimo was against the law. I painted because I wanted to, but also because I had to . It was the only way to express what I was thinking, what I was seeing.”

That explanation is common among the former colony’s artists, from noted painters like Malagatana and sculptors like Alberto Chissano to lesser-known figures, like Sumbana. Exposure to world art was hardly the prime inspiration since there is no art museum in the country, little experience offered in schools, and few books on the subject — especially for poor black families.

As Sumbana said, “I have seen only one print from an artist outside of Mozambique. It was a Picasso. It was beautiful. I want to see more, somehow.”

He may not see more “world art” soon, but the exposure to local artists has already increased. The small but growing artists’ community is getting active encouragement from the new government. Several exhibits of “ethnic art” are being set up throughout the country. Walls of business and government offices are increasingly splashed with the bright colors of Mozambican artists. Even the colonial monuments to Portuguese explorers and officials have been torn down and will be replaced with sculpture and monuments to Mozambique and Frelimo figures.

As a result, the young painter says many of his colleagues have also shifted their subject matter. “We are free now to draw and paint and write what we want. Anything.” he adds with emphasis. “I still see misery in the world. But the new freedom here, that is the first sign of hope. The spirit and soul of the Mozambique people were liberated with independence and it shows now. There is pride expressed now. Before it was fear.

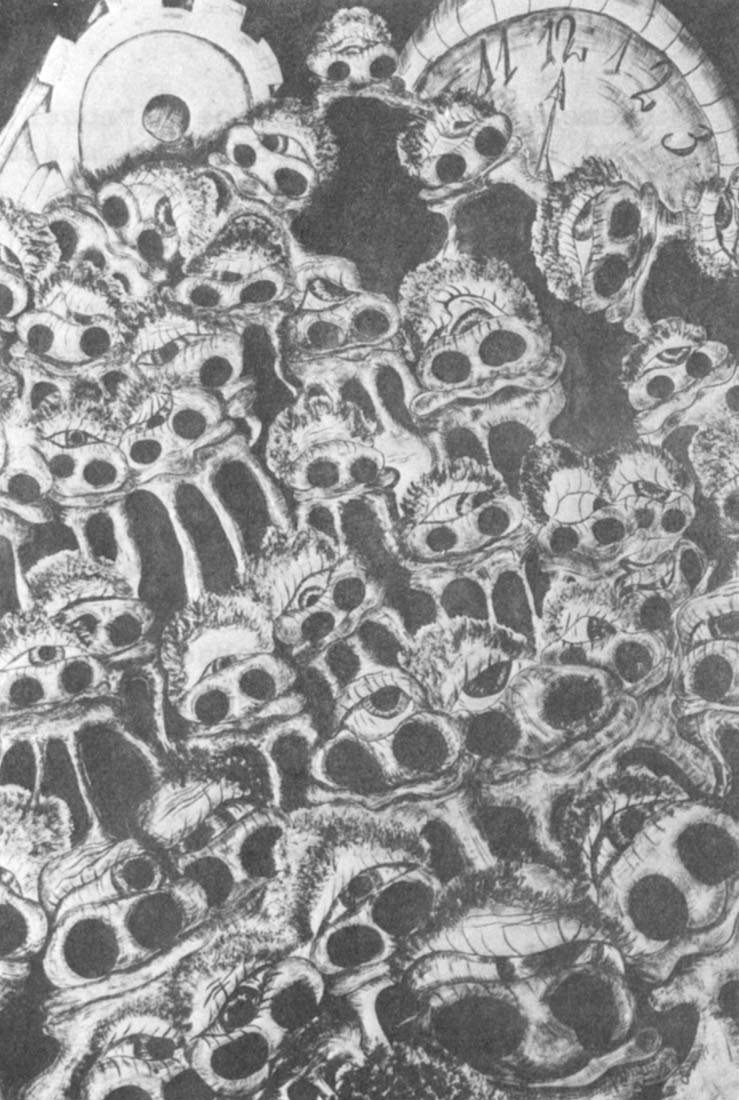

Untitled work on the unstoppable growth and danger of gossip and rumor

Commercial benefits of the creative arts are never mentioned as a motive. Most of Sumbana’s works have been given away, mainly to Frelimo. He acts surprised when asked why he does not sell them. “They are seen now, more than if there were in houses. That is better for them.”

His balled, tight navy blue sweater, sleeves ending just below the elbows, reveals his poverty. He wants to continue his studies at a university, preferably in economics, but money is a problem. His only immediate concern about income is to have enough to buy more oils and the tackboard on which he paints, since canvas is either unavailable or too expensive. He has kept only two of his paintings; a small incomplete photo album is the only trace of his progress.

It does not occur to him to keep his work. “This is the way I’ve learned to express myself. This is the way I speak. I want others to listen through my paintings, to understand our problems. And now,” he adds with a smile, “perhaps also to see that there are, for the first time, some answers for us.”

Received in New York July 7, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.