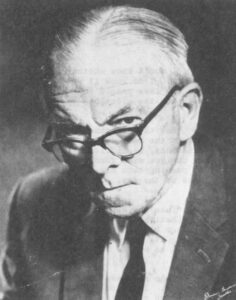

Dr. Alan Paton, noted author, columnist and politician, has been a leading advocate of change in South Africa’s racial laws for 50 years, perhaps the longest and loudest voice of opposition throughout that volatile period.

Although this is an era heralded for detente and a softening of government policy in South Africa, Dr. Paton’s analysis offers a slightly different perspective.

Robin Wright recently visited the septuagenarian author at his home in Kloof, talked with him about the issues of the day, drove with him through the Valley of One Thousand Hills surrounding his home, toured the little Zulu church he helped build, witnessed his involvement as advisor to local Africans, and learned the depth of his feeling for his country, his people and his government. Wright’s assessment is recorded in the following report.

Kloof, South Africa

The setting was Natal’s Valley of One Thousand Hills, in daylight a maze of fertile serenity, at dusk a mirage-like entanglement of overlapping shadows. Restful yet intense with the wealth of rich earth and haunting power, it is a sight to which men dream of retiring.

But it also offers the type of inspiration that keeps one from retreating. It is inspiring South Africa at its most provocative.

It is from here, in a comfortable but simple book-lined study overlooking the valley, that Alan Paton, noted politician, author and humanitarian, writes about the issues that threaten the fragile peacefulness of this area.

Throughout his life, Dr. Paton has been one of the leading “rational rebels” campaigning for change in South Africa’s racial laws. His moving Cry, the Beloved Country,–a fictional account of black-white relations, which one reviewer predicted may be remembered longer than any novel of 1948–is his best known work abroad. At home he is remembered as president of the now-defunct Liberal Party, columnist, prison reformer, and friend and advisor to the country’s “silenced majorities” — Coloreds, Asians and Blacks.

Throughout his life, Dr. Paton has been one of the leading “rational rebels” campaigning for change in South Africa’s racial laws. His moving Cry, the Beloved Country,–a fictional account of black-white relations, which one reviewer predicted may be remembered longer than any novel of 1948–is his best known work abroad. At home he is remembered as president of the now-defunct Liberal Party, columnist, prison reformer, and friend and advisor to the country’s “silenced majorities” — Coloreds, Asians and Blacks.

Now 72, Dr. Paton has perhaps the longest record of open dissent in South Africa. His study is full of the tributes, books and momentos that record this involvement, from a plaque commemorating his first job as social reformer and principle of Diepklouf Reformatory for delinquent African boys to his later awards — the 1960 Freedom Award and honorary degrees from universities all over the world.

Two pictures ornament the walls — one of the late Chief Albert Luthuli, the “banned” author of Let My People Go and president of the also “banned” African National Congres, and the second of a black man in jail, hand gripping a bar, face contorted with desperation.

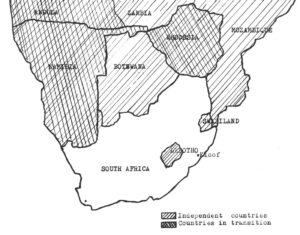

Although retired from the politics these pictures represent, Dr. Paton continues to speak out on the issues of the day — detente in southern Africa, the impact of independence this year in the two nearby Portuguese territories (Mozambique and Angola), racial laws and the prospects for change — both evolutionary and revolutionary — in South Africa.

During a period heralded for shifting government policy, Dr. Paton’s analysis — based on a perspective of 50 years of involvement — suggests a different picture. He remains as critical today as he was at the beginning of his career, and his warnings are perhaps even more provocative because of the time element:

“Anyone with sense realizes South Africa is at a crossroads. The changes here so far have been trivial. There will need to be many more to guarantee a peaceful future,” the gruff but kindly figure said from behind a desk piled with manuscript proofs.

“I don’t know whether change will be evolutionary or revolutionary. I do know it will be difficult to reverse in full gear from the laws passed in the past 27 years (since the Nationalist Party won the elections of 1948).”

“How the government can undo these laws, after justifying them in the most exaggerated language, repeatedly using Biblical quotations, is difficult to see. If you make fundamental laws, how can you make fundamental changes in them?” he asked, pausing and pushing back his bifocals, as if waiting for an answer to the issue of the day.

“Take the Mixed Marriages Act, one of the first laws the Nats (Nationalists) enacted. (Passed in 1949, it prohibits marriage between races). I can’t see the government just repealing it, and there is no ground in between. Yet the world sees it as one of the most discriminatory”.

“I do not have much praise for our Prime Minister (John Vorster). But I do think hoe realizes that establishing relations with black countries is no good unless there is also change within the country. This will be difficult in a country where the majority of those in power truly believe in their own superiority and fear the consequences of giving power to the black man.”

“More and more people are trying to hide these feelings today, but they still exist and remain the concealed root of our problems. Fear is the great operator here — and it is the government’s hard task to accommodate this fear while still easing discrimination,” he added, pausing again and looking out over the valley.

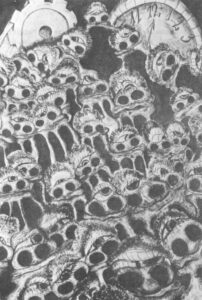

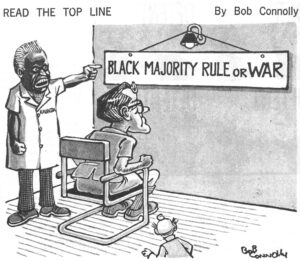

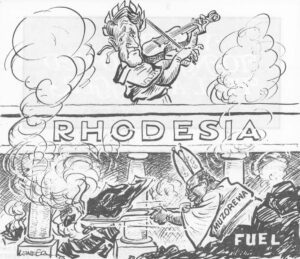

Editorial cartoon from South African paper:

“I do not have much praise for our Prime Minister. But I do think he realizes that establishing relations with black countries is no good unless there is also change within the country.”

— Dr. Alan Paton

Dr. Paton began writing openly about these fears as far back as 1958, at the beginning of the tide of independence that swept Africa. In one of his first “The Long View” columns in Contact — a publication blatantly named as a counter to the apartheid or racial separation policy — he explained:

“These are the fears of rising African nationalism, the white man’s fears of freeing the giant who may turn and rend him, the white man’s fears of appearing to be a traitor to his race, culture and civilization.”

“Under the influence of these fears, words such as ‘liberation,’ and ‘freedom’ take on a frightening quality. Even words such as ‘democracy,’ ‘human rights,’ ‘brotherhood,’ acquire a new and unpleasant meaning, so that some who once upheld them as ideals may now sneer at them as delusions.”

The result of these fears, he wrote, is that “we are further away from the nonwhite people of our country than we have ever been before.”

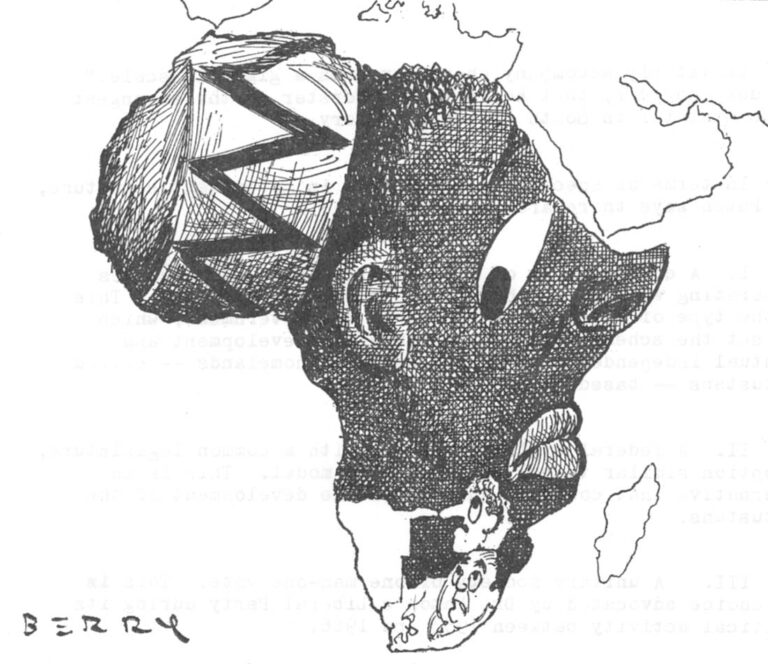

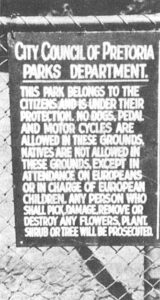

“South Africa is a white fortress,” he commented in the first edition of Contact. “Each day, each month, each year the Nationalists make it stronger. They make the walls thicker; they make them higher. Each year more and more of the white inhabitants are called from other jobs. They have to guard the fortress.

“Yet, in the long view, no one believes that the fortress will endure. Sooner or later it must yield. But till then the inhabitants must be on guard…. The bells are tolling for the death of an age. They are tolling for the death of white supremacy.”

Seventeen years after he first outlined it, Dr. Paton says the fundamental political problem has not changed: “It is to move from white supremacy to nonracial democracy as quickly, as soundly, as we can,” he wrote, again in 1958. “We have to do this because we ought to. But we also have to do it because we have to. The world demands it, quite gently now, more loudly tomorrow.”

That tomorrow is here, he says, using the analogy of a pot of boiling water to explain the current situation. “We are always told that we must not force the lid of the pot down otherwise it will blow to pieces. But the fact is that it is just as difficult to take the lid off the pot.”

Yet in speeches at the United Nations and at home the government has promised to ease discrimination or “cool the boiling pot,” Dr. Paton points out. The noted author suggests that the best way to handle the issue is to dampen the fire underneath: to remove the discriminatory legislation which kept the pot at full steam.”

Fundamental to significant change is:

Free education for Africans.

The setting aside of group areas for free occupation by all races.

Elimination of the wage gap.

Appeal of the Immorality and Mixed Marriages Acts.

Removal of racial classification.

Removal of the migratory labor system.

Fairer distribution of land.

Reconsideration of the system of political detention.

Close examination of the government’s security legisiation and machinery.

Dr. Paton does not underestimate the difficulty or impact of these changes. “The problem is that Mr. Vorster must move fast enough to abate world hostility and give confidence to the black people that there is a possible future for them without revolution, and at the same time avoid making his play so fast that he loses political power.”

It will “require great personal strength and great personal skill to lead South Africans through the emotional storm that will inevitably accompany change on such a gigantic scale.” He adds, however, that he feels Mr. Vorster is the strongest Prime Minister in South Africa’s history.

In terms of specific alternatives in government structure, Dr. Paton says there are three choices:

A commonwealth of eight to ten independent states cooperating with each other to their mutual advantage. This is the type of alternative backed by the government, which has set the scheme in motion through the development and eventual independence of the eight black homelands — called Bantustans — based on tribal ties.

A federal system of states with a common legislature, an option similar to the United States model. This is an alternative that could be adapted to the development of the bantustans.

A unitary society of one man-one vote. This is the choice advocated by Dr. Paton’s Liberal Party during its political activity between 1953 and 1966.

The majority is not enthusiastic about the first option, according to Dr. Paton, and “the Afrikaner (the section of the white community that dominates the government) would rather die than agree to a unitary state. He would never allow a black man to sit as his equal in Cape Town (where Parliament meets).”

This attitude of the Afrikaner, not just the feelings of the blacks, is the real key to South Africa’s future, the former -Liberal Party leader contends. The Afrikaner’s history of struggle in South Africa has led him to believe in the importance of his ethnic group and the need to fight for the survival of it as a distinct faction. “This has led to an irrational and extreme form of nationalism,” Dr. Paton explains.

In a speech delivered in the United States, the septuagenarian author further explained the dilemma:

“The Afrikaner is a divided creature, torn between his fears for his own safety and his desire for his own survival on the one hand, and by those ideas of justice and love which are at the heart of his religion.”

“We are witnessing today a struggle in the hearts of men, white men, between the claims of justice and of survival, of conscience and of fear.”

The problem is complicated for the Afrikaner in that, after 27 years in power, non-Afrikaners now see the political issue of apartheid as a personal extension of the Afrikaner.

It has created “the difficult problem of how to be altogether anti-apartheid, and not at all anti-Afrikaner, a problem that the Afrikaner himself has made intensely difficult for us all,” Dr. Paton laments.

Yet the Freedom Award winner, his bushy white eyebrows knit together in a thoughtful frown, vehemently says he wants to see the Afrikaner survive in South Africa — “for one noble reason and one selfish.”

Yet the Freedom Award winner, his bushy white eyebrows knit together in a thoughtful frown, vehemently says he wants to see the Afrikaner survive in South Africa — “for one noble reason and one selfish.”

“The noble reason is that my ancestors (the English) are largely responsible for making the Afrikaner the way he is. The historical conflicts between the English and the Afrikaner instilled the initial fear for his survival. The selfish reason is that if the Afrikaner ‘goes,’ so do I — and the other white English (speaking) South Africans.”

Reversing this attitude developed over 300 years — when the Afrikaner’s Dutch ancestors first settled in South Africa — is the key. The problem, Dr. Paton says again, is time.

“There is no time for slow, political development. The minorities won’t put up with repressive legislation for another 27 years. There is no doubt black determination not to be pushed around will grow.”

The intensity of this belief was best explained by the black preacher, the main character in Cry, the Beloved Country: “I have one great fear in my heart, that one day, when they turn to loving, they will find we are turned to hating.”

How much time does South Africa have? “I just don’t know,” Dr. Paton tells the many who ask. As he wrote in the last paragraph of Cry: “But when the dawn will come of our emancipation, from the fear of bondage and the bondage of fear, why, that is a secret.”

Yet the author remains an optimist. Deeply religious, always claiming his “Christian conscience” is the force that led him to fight for a non-racial society, he continues to tell friends to “beware of melancholy.” Throughout his criticism he tries to offer constructive, viable alternatives. He points out the country’s strengths as well as its weaknesses.

Besides the obvious steps taken on Rhodesia and Namibia (South West Africa), Dr. Paton says there are other signs of change that provide hope:

Besides the obvious steps taken on Rhodesia and Namibia (South West Africa), Dr. Paton says there are other signs of change that provide hope:

Although South Africa is spending more on defense than in any point in its history, he says that the government is no longer “talking boastfully” about its strength and ability to withstand any military challenges.

The government continues to cooperate with Mozambique, under a new Marxist-oriented government since June 25, on matters concerning railway and harbor use, hydro-electric power sources and migrant labor. Also, the disappearance of Mozambique as a buffer state has not led to fear of spreading communism in South Africa. That fear was, ironically, stronger in the 1960s than it is now, he feels.

There is greater contact between races. Even though token at this stage, it will at least help break down the stereotypes behind discrimination.

The surfacing of several Afrikaner “liberals,” among both young and old, who are questioning the system and speaking out about their doubts. Even the Afrikaner press is no longer “just a mouthpiece” for government policy. Over the past three years this segment of the press has opened a critical dialogue with Afrikaner officials.

There is definitely reason for hope. And for those who doubt, Dr. Paton offers an excerpt from his speech after being awarded the Freedom Medal in 1960:

“Stand firm by what you believe; do not tax yourself beyond endurance, yet calculate clearly and coldly how much endurance you have; don’t waste your breath and corrupt your character by cursing your rulers; don’t become obsessed with them; keep your friendships alive and warm, especially those with other races; beware of melancholy and resist it actively if it assails you; and give thanks for the courage of others in this fear-ridded country.”

Received in New York on August 25, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.