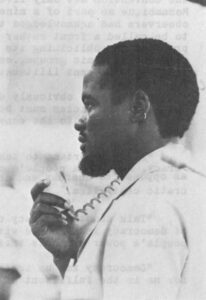

Filipe looked like a walking advertisement for the new government, t-shirt with the new flag stretched tightly across his chest, plastic pinkie ring also with the new flag, tiny metal chest pin engraved with the face of the national liberation movement’s founder, and second-hand battle fatigue trousers once worn by the liberation army.

“Can you imagine,” he asked rhetorically, almost in disbelief, “I can walk down the street like this and all I get is smiles or nods from people who share my happiness, my pride.”

“Five years ago my brother was arrested and put in prison for carrying a letter, one little piece of paper, with the name of Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) across the top of it. It was not even official. It was just a letter from a friend, although the Portuguese did not believe.”

“He spent four years in prison because of that little piece of paper. And today, look,” the young teenager pointed to his chest, “I can say Frelimo all I want and no one will do anything to me.” He was beaming.

Filipe’s attire is not an unusual sight on the streets of Lourenco Marques. There are many adults as well as youths who sport the new “Frelimo fashion,” from the variety of chest pin, to clothing splashed with slogans or pictures of the Frelimo president Samora Machel and the army green caps, jackets or satchels used by the Frelimo army.

As the curtain goes up on independence in Mozambique there are some dramatic changes in the sets and props on the stage of this southeast African country. Although Portuguese colonialists had penetrated this territory for 500 years, it took but a few short months for Mozambicans to shed many of the trademarks of the colonial era.

The nine-month interim period between Portuguese rule and the complete take over by Frelimo, on June 25, has clearly served as a transition for more than government. Every aspect of life in Mozambique reflects the political change — from fashion to school curricula to the media.

Walking down the streets of Lourenco Marques Filipe pointed to some of the changes. “Look, I can now buy a book on Marx or Lenin,” he said as he peered into a bookstore window. “And there’s something on the pan-African movement, even a dictionary of the geographic names of Mozambique, the proper names, the ones we gave the streets and cities and plazas before the Portuguese renamed everything after their own discoverers, leaders and military personnel.”

In front of the bookstore there was a billboard, one of the many that have sprouted from the city pavements since an agreement was signed last September 7 granting independence to Mozambique on June 25.

“At least half the businesses in the city have these,” the black youth explained. “Each provides a little news, pictures and some stories on how that business relates to Mozambique culture or maybe things about what workers hope to do within their companies.”

“Newspapers, they are the same way. We no longer read just news about Portugal but about the victories of our brothers in the liberation movements in Vietnam and Cambodia, about developments in Tanzania or Zambia and other African countries.”

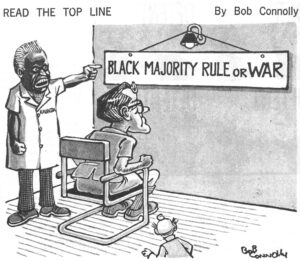

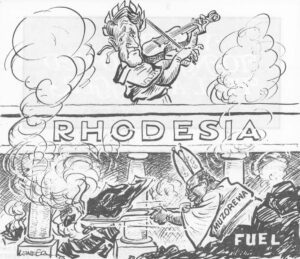

“We can hear news now on the radio about Zimbabwe and Namibia. They are no longer referred to as Rhodesia or South West Africa, you know,” he almost smirked. “Fantastic,” he shook his head, smiling.

Next to the bookstore was one of the many sidewalk cafes that are scattered throughout the city. “See, women,” he pointed to some of the cafe’s customers sipping coffee and watching passers-by.

“One of the basic goals of Frelimo is equality of women, a real change from the chauvinistic Portuguese way of life. There are not that many of them yet, but it’s a beginning. You used never to see women asserting themselves, black or white. Only men used to sit here. Really,” he said with emphasis.

A friend named Marcus approached and interrupted the conversation with some “startling,” news. “Do you know what docked today?” he asked, referring to the Lourenco Marques harbor, the second busiest port in Africa.

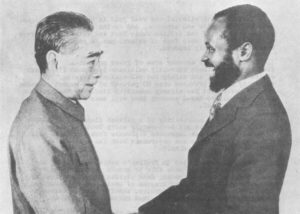

Before allowing time for an answer he said, “A Russian ship. A huge Soviet ship. That’s a first. They say the port isn’t as busy as it was under the Portuguese, but you just wait until after independence. They will all be here, all of our friends.”

The conversation turned to school, about which both youths expressed some unexpected enthusiasm. “It’s much more interesting now. We don’t just learn about Portugal or when the Portuguese came, like how Vaso da Gama ‘discovered’ Mozambique in 1498 or about Lourenco Marques’ arrival in 1544,” Marcus said.

When asked about specifics he elaborated: “History is about Frelimo, about Mozambique. The dates we learn are June 25, 1962 (Frelimo’s founding), September 25, 1964 (launching Of Frelimo military operation), February 3, 1969 (assassination of Frelimo founder Eduardo Mondlane by a mail bomb), April 25, 1974 (Portugal’s coup), September 7, 1974 (signing of Lusaka agreement on Mozambique independence) and September 20, 1974 (investiture of transition government),” he rattled off with pride.

“I can care about something that means something to me, when it’s about my country, not someplace 10,000 miles away,” Marcus added.

“Everyone is learning these days, it seems,” Filipe interjected. “My school is even busier at nights now than it is in the days with adults who didn’t go to school or young people who work during the day getting instruction under the alphabetization program. The electricity bill must be huge,” he laughed.

Asked if there were any changes that had taken place during the transition that displeased them, Marcus offered: “Sure there are plenty of things that are affected because of the problems we face.”

“My mother is complaining all the time about the things she can’t get at the store, like soup or mayonnaise or brown sugar. And my father can’t get foreign cigarettes. I have a friend who wanted to buy a bottle of foreign brandy for a special occasion. He ended up buying it by the glass at a hotel. Cost him $22.”

Mozambique’s imports have recently been twice the amount it is able to export and the current shortage of foreign exchange led the new government to put a “graded” ban on imports, depending on necessity.

“Transportation is tough too,” Filipe said. “The buses are jammed since half the taxis, owned mainly by Portuguese, have left. You even see whites on the buses these days. They get tired of waiting an hour or more for a ride.”

“And if you want to go outside the city it takes twice as long because of all the roadblocks. You have to check with Frelimo soldiers every few miles, it seems. I understand why of course. But it is time-consuming and annoying to even those of us who want Frelimo to take over.”

“I’d hate to get really sick now,” Marcus added. “There are no doctors anywhere. And I can’t afford to go to Swaziland or South Africa, like the whites can, to get medical attention.” As a result of the mass exodus by 103,000 Portuguese, officials now claim there are only about 50 certified doctors left to serve a population of nine million.

“But things will work out,” Filipe said optimistically. “The people in this country are so happy to be free of Portuguese restrictions, not to have to worry about the DGS or PIDE (secret police) spies watching our every move, that we can endure it. The spirit of freedom will carry us through these first rough moments.”

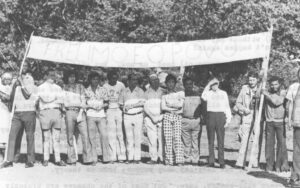

The boys got ready to leave. “We have to get to the May Day celebration,” Filipe explained. “It’s the first we’ve had here in Mozambique. The first of many.”

Received in New York on May 12, 1975

May 12, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.