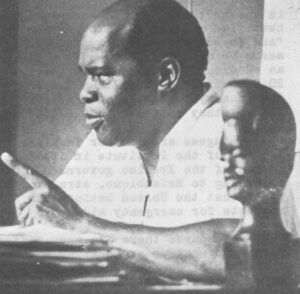

At first appearance the only things African about Janet Mondlane are her batik print shirts. Yet the American-born mother of three is a leading member and founder of one of Africa’s most heralded liberation movements, which on June 25 will take over full control of the Mozambique government.

Throughout the liberation war Mrs. Mondlane served as director of the Mozambique Institute, coordinating the non-military activities of Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique). A look at her role reveals much about the level of experience the new government has had in the tasks it now faces on a national scale. Robin Wright recently talked with Mrs. Mondlane in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania as she was winding down the work at the Institute and getting ready for the move to Mozambique.

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Off a dusty road on the outskirts of the bustling east African port city of Dar es Salaam stretches an unimpressive, single-story concrete building. Starkly utilitarian in design, furnishings and decor, it has served for the Past 13 years as one of two facilities that housed a revolution, the liberation struggle to end 500 years of Portuguese domination in neighboring Mozambique.

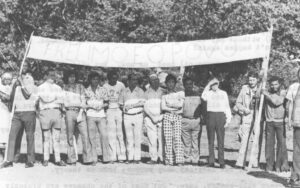

It was to this simple structure that Mozambique refugees and exiles flocked to join the independence movement. It was here that Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) decided after two years of peaceful operations to cross the Tanzanian border and take up arms against the Portuguese. And it was here that leaders devised the entire strategy for political and social development of the liberated zones, ultimately amounting to one-third of the country.

But on June 25 Mozambique gains full independence, marking the formal end of the bitter guerrilla war that led to new governments in both Mozambique and Portugal. And at that time this unpretentious but important building known as the Mozambique Institute will close down and the last of its staff will return home to take part in the new government. Home, that is, for everyone except the Institute’s director, who has never lived in the land she worked so hard to liberate.

“Comrade” Janet, as she is called by her colleagues, is an American. Or, as she prefers to say, she was ‘born, raised and educated in the United States. But as one of the founders of Frelimo, and after 13 years of working for the government, Janet Mondlane says she is as anxious to go “home” as the other Mozambicans now helping to plan for impending independence from the Institute’s cubicle offices.

“It will be strange. I don’t know quite what to expect,” she said from behind the large wooden desk that takes up half of her small informal office. “Liberation came so suddenly with the Portuguese coup (in April, 1974). We had calculated that it would take eight to ten years before we controlled the entire country. I’ve had so such to do since the transition that I haven’t had time to think about the move. But it means so much…. I still find it hard to believe.” She paused, “It’s been a long haul.”

For Janet Mondlane it has been an unusually long haul, with some unique twists, from an average Middle American upbringing to a successful revolutionary in Africa.

Born Janet Rae Johnson in a small Illinois town 41 years ago, she was the product of the staid American midwest during the post-war era. Her youth centered around church, pianos family and domestic interests, sewing, embroidery and cooking.

“Straight,” she recalled about those early years. “I was really a small town American girl with little experience and very narrow-minded views.” Then again with a reflective, amused smile, “Very straight.”

The transformation began in 1951, at the age Of 17, when, at a church camp in Geneva, Wisconsin she met Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane, a Mozambican studying in the United States. He spoke at one of the camp sessions on the future of Africa. He impressed her and, despite initial rebuffs, she pursued him. “I decided to grab him quickly,” she laughed. Five years later, after she had finished her B.A. and he had finished his M.A., they were married.

Their differences were many. She was 22, he was 36. She was American, he was African. She was white, he was black. She came from a “real WASP upper middle-class family”; her father was a mechanical engineer. He came from a poor, polygamous family in rural Mozambique; his father was a tribal chief. Her background was apolitical and “pure capitalist,” he was a devout socialist.

The gaps were not closed merely because of marriage, she claimed adamantly. “I didn’t just marry into the revolution,” she smiled, anticipating the question. “I had always wanted to go to Africa, from the age of nine. I had intended to become a doctor and work as a medical missionary. And my M.A. from Boston University was in African studies.

“No,” she said slowly, large brown eyes squinting, thinking back as her hand fiddled with the old de-lasticized watch that hung like a bangle on her wrist. “The change is as much from our experience in the United States, where several bad experiences opened my eyes.

“It was tough for an interracial couple in the mid-50s. It was then that I turned from the church because they discouraged our marriage. That was a big smirch. I felt the church did not follow its own doctrine. Later the church organization that was to sponsor Eduardo’s Ph.D. thesis research unilaterally cancelled the scholarship for they disapproved of such marriages.

“Then, as an interracial couple in Boston — that was really an experience. We could not even find housing. Finally through the university we found a place, a miserable place for which we paid a tremendously high price.”

Similar experiences during the first six years of their marriage “grew” on her and by the time Mondlane decided to quit his job as professor of sociology at Syracuse University to return to Africa and organize the many Mozambique liberation factions into a united front she was “fully politicized.” I wanted to get involved in changing the system as much an he did, she explained.

From the time they reached Dar es Salaam — a city that offered support and facilities for the Mozambique liberation movement — in 1963 she never played the role of mere wife, “even though I had to fight the image for a long time.” Her initial roles as fundraiser, public relations agent, organizational assistant and social welfare expert — “I did a little of everything” — evolved into the directorship of the Mozambique Institute, the non-military branch of Frelimo that has often been called “a front for the Front.”

That she is a power in her own right has been proved a number of times. Shortly after the assassination of Eduardo Mondlane by a mail bomb on February 3, 1969, several Frelimo officials became involved in a power struggle and in the process attempted to take over the Institute.

“But Janet would never stand for simply being The Widow,” a colleague at the Institute remarked. “She is a strong personality and as deeply committed to Mozambique as anyone here. While she had arrived as Eduardo’s wife, she had by 1969 developed into much more. She had a job and she intended to stick to it.” Samora Machel, subsequently elected to succeed Mondlane as Frelimo president, stood by Janet and supported her continued role at the Institute.

It happened at a crucial time for the Institute and a major turning point for Frelimo. In 1968 Frelimo had held its second Congress — the highest level of the movement — and decided to put as much emphasis on reconstruction of the liberated areas as on the guerrilla campaign. Previously the Institute had run its education, health and refugee rehabilitation programs mainly in Tanzania. Now projects were to be set up in Mozambique itself, “as proof we really controlled the area and as proof of our intentions,” she explained.

It was a novel step, and one of the aspects that makes Frelimo unique among African liberation movements. Nowhere else in sub-Sahara Africa but in the three Portuguese colonies (Mozambique, Angola and Guinea-Bissau) did a liberation movement wage a full military campaign for a prolonged period. And Mozambique was unique among the three because large-scale, nonmilitary programs were set up during the war. “We decided to consolidate our victories and to begin rebuilding the nation, getting a further edge on the enemy,” Mrs. Mondlane explained.

Shortly before his death Mondlane wrote about the decision: “One of the chief lessons to be drawn from nearly four years of war in Mozambique is that liberation does not consist merely of driving out the Portuguese authority, but also of constructing a new country. This construction must be undertaken even while the colonial state is in the process of being destroyed…. We are having now to evolve structures and make decisions which will set the pattern for the future national government.”

By 1969 Frelimo controlled the major portion of two provinces and portions of two others, all in the North. Although the most sparsely populated areas of the country, this still involved approximately 800,000 people, just under ten percent of the entire Mozambique population.

“We had to provide material goods since supplies would no longer come from the commercial areas in the South. This involved everything from soap and matches to clothes and food. Then medical and educational services had to be established, and administrative and judicial systems organized,” Mrs. Mondlane outlined.

“For a time the problem was acute,” her husband noted in his book The Struggle for Mozambique. “We had been unprepared for the extent of work before us and we lacked experience in most of the fields where we needed it. In some areas, shortages were serious and where the peasants did not understand the reasons they were withdrawing their support from the struggle and in some instances leaving the region altogether.”

The problems were not just organizational. “We had to find funds from sympathetic governments or private sources, and train personnel, especially in the field of health. Even determining just what was needed caused problems as the people were so spread out,” she recalled.

Communication was a singularly difficult task. Although Frelimo strategy was to build an underground political base in an area before moving in militarily, this didn’t mean the largely peasant populations were ready for what was to happen after an area was “liberated.” Tribal loyalties and superstition offered formidable obstacles.

Frelimo proposed to install an extremely alien system, one that challenged the authority of the local chief and the cultural traditions of a tribe. The administration of villages was reorganized on the basis of people’s committees elected by the entire population. And agriculture was reorganized so that producers worked in cooperatives under the direction of the local party. This system took away from the chief his traditional role as organizer of both political and economic life and required massive reorientation or politicalization programs to gain the support of the people.

Janet Mondlane and her small staff of Mozambique exiles and sympathizers coordinated most of the activity and personnel for these new programs, with complete control over the planning of social services — as well as complete responsibility for financing them. Janet Mondlane’s midwest twang became well known among foundations, political organizations and newspaper editors all over the world. Her blitz trips abroad to raise money and support were then keeping her away from the Institute and her family of three children up to two months each year; it was during one such trip to Europe that her husband was killed.

Janet Mondlane and her small staff of Mozambique exiles and sympathizers coordinated most of the activity and personnel for these new programs, with complete control over the planning of social services — as well as complete responsibility for financing them. Janet Mondlane’s midwest twang became well known among foundations, political organizations and newspaper editors all over the world. Her blitz trips abroad to raise money and support were then keeping her away from the Institute and her family of three children up to two months each year; it was during one such trip to Europe that her husband was killed.

“Every minute of work was worth it,” she contends. “There were long term benefits we did not fully realize at the time. What we did in the liberated zones is in many ways a microcosm of what we have to do now in the entire country.”

“For examples since most of the doctors have fled the country we have to establish a health system almost from scratch, as we did in the North. (Several sources agree that there are now about 50 certified doctors left to serve a population of nine million.) “And in education we have to deal with 97 percent illiteracy, which means we must provide a system for adults as well as children, again as we did in the North. In the past six years we have taught over 20,000 children, more than the Portuguese were doing in the rest of the country.” (While outside sources do not question the 20,000 figure, they estimate that illiteracy is more like 80 percent).

Refugees are another familiar problem. They were a primary concern of the Institute in its early days and are again in the early period of the Frelimo government. About 100,000 are estimated to be returning to Mozambique, straining already limited resources to the point that the United Nations has already answered government requests for emergency aid.

“Of course there are many differences in what we did in the North and what we are dealing with now. We have to work with a large urban sector now; the demography is much more diverse. But we have experience at least in the organization and services, and that is what has made our struggle different and successful,” she smiled, nodding her head and acknowledging her biased pride.

The winding down of the Institute’s specific functions in Tanzania has not diminished its importance or work — nor the role and workload of Janet Mondlane. Most of the staff from Frelimo’s military office in town have moved to the Institute’s office on Ki1we Road, where all are involved in planning for the future — in Mozambique. As one Tanzanian remarked, “The Institute is no longer a front for Frelimo. It is now where everyone of any importance is. Mozambique is now being run from a small institute in Tanzania.”

That is almost true. Transitional government officials in Lourenco Marques, Mozambique’s capital, commute regularly to Dar es Salaam to confer on plans for implementation after June 25. And all foreign missions check first in Dar es Salaam, where Frelimo President Samora Machel and Vice President Marcelino Dos Santos also remain, before going to Mozambique,

Quietly, almost surreptitiously, Janet Mondlane continues to run the show, whether organizing a last-minute reception for foreign dignitaries, inspecting proposals for health programs, or looking for trucks to be loaded for shipment of goods to needy areas.

“Janet has been the supporting force throughout it all,” Vice President Dos Santos attested. “Her knowledge and experience will be vital in planning for the future of Mozambique,” another colleague vouched. “We would be nowhere near as prepared without her drive and ability. She has been like, what do you call it, a godmother to the revolution.”

Received May 12, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.