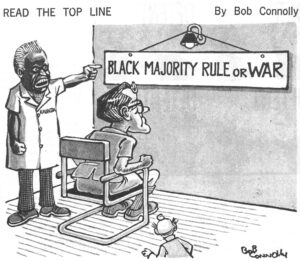

As the tenth anniversary of its unilateral independence from Britain approaches, the Rhodesian government faces the most dramatic decision in its history: settlement with black nationalists or war. Prime Minister Ian Smith has stalled on the issue of black majority rule for a decade and through four settlement efforts, but now increased internal and external pressures are forcing him to face the alternatives head on.

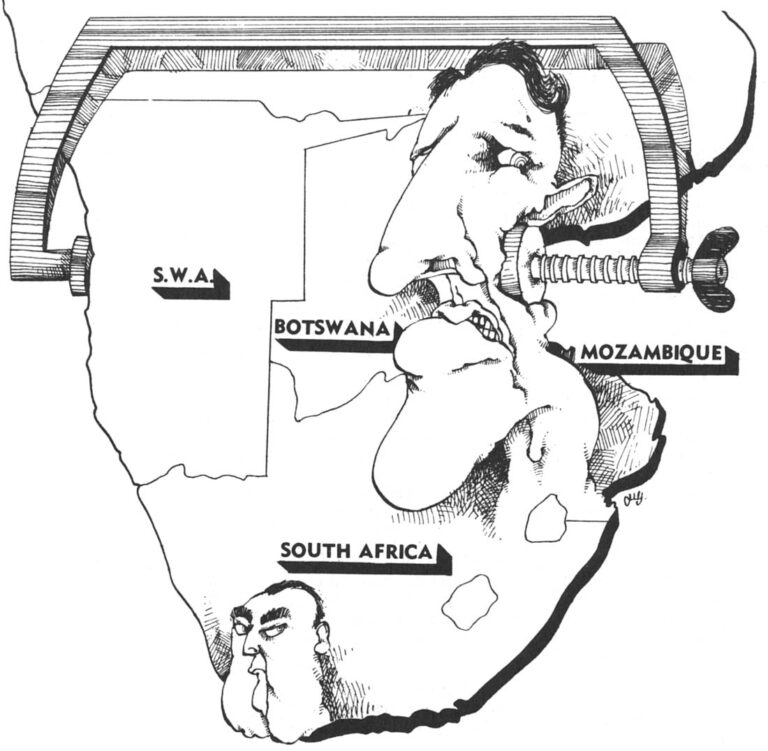

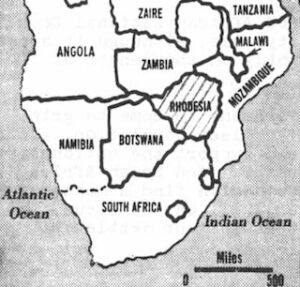

The changing political face of southern Africa in the past year is part of the reason. Mozambique — the neighbor with the longest common border — came under black rule in June. Angola to the northwest is scheduled to become independent on Nov. 11, the same day as the Rhodesian anniversary. And Southwest Africa has started the constitutional talks leading to independence.

But more importantly four neighboring black African countries have moved to back the demands of Rhodesian nationalists, to the point of supporting a war if necessary. And South Africa, Rhodesia’s closest ally, has demanded that Mr. Smith settle.

Robin Wright covered negotiations at Victoria Falls and spent a month in Rhodesia talking with blacks and whites at all levels. The following report reflects the grim situation in the southern African country as it nears a decade of “independence.”

Salisbury, Rhodesia

In the corner of a posh downtown club in the sleepy Rhodesian capital of Salisbury, a burly middle-aged Rhodesian turned to the foreign correspondent who was talking with colleagues nearby.

“Excuse me,” he interrupted. “I hear you talking about the, uh, situation here, and I have a question I need to ask you.” He paused, waiting consent, then blurted: “How much time have we got?”

As the confrontation between black nationalists and the white Rhodesian government of Prime Minister Ian Smith reaches the crisis point over the issue of black majority rule, that question is asked frequently throughout the country.

Even the blacks, who dominate the population at a ratio of 22:1, reflect the same anxiety. At the shabby Queens Hotel on the outskirts of Salisbury two nights after the questioning session by a white, the same correspondent conversed with blacks and was asked a similar question, with a slightly different twist. “How much longer?” a young black queried.

In response to both men, the journalist replied, “It depends….”

There are so many variables in the complex Rhodesian constitutional crisis that it is difficult to even predict the two sides’ strategies, much less a time table.

Only three factors are known:

Prime Minister Ian Smith is adamantly opposed to black majority rule. In a speech at Gwanda just two days before talks opened on the Victoria Falls bridge in August, he infuriated black nationalists by declaring: “We have never had a policy to hand over our country to any black majority government, and as far as I am concerned, we never will.”

Both branches of the recently-divided African National Council (ANC) are equally adamant about black majority rule, although it appears the moderate and militant factions vary slightly on the length of a transition period.

The time has come for the white government to come to grips with the question of the role for its majority black population. Four African countries have moved to strengthen and support the nationalists, to the point of aiding a war effort if necessary. And South Africa, Rhodesia’s closest ally, has demanded that Mr. Smith find a means of settlement. The Prime Minister can no longer stall on the issue, as he has done successfully for ten years and through four settlement efforts.

At this-final crossroad, Mr. Smith appears to have two alternatives: grant majority rule or fight it out in a guerrilla war. There is a slight chance the Prime Minister will be able to sell a deal short of majority rule to the moderate nationalists, who recently took over the ANC leadership by electing Joshua Nkomo president. But political observers feel that such a deal would not be long-lived.

As the correspondent indicated, the outcome “depends” on internal as well as external action.

All sides involved feel an attempt should first be made internally to find a mutually satisfactory solution. That is what made the four black African countries and South Africa push the two sides together at Victoria Falls on August 25.

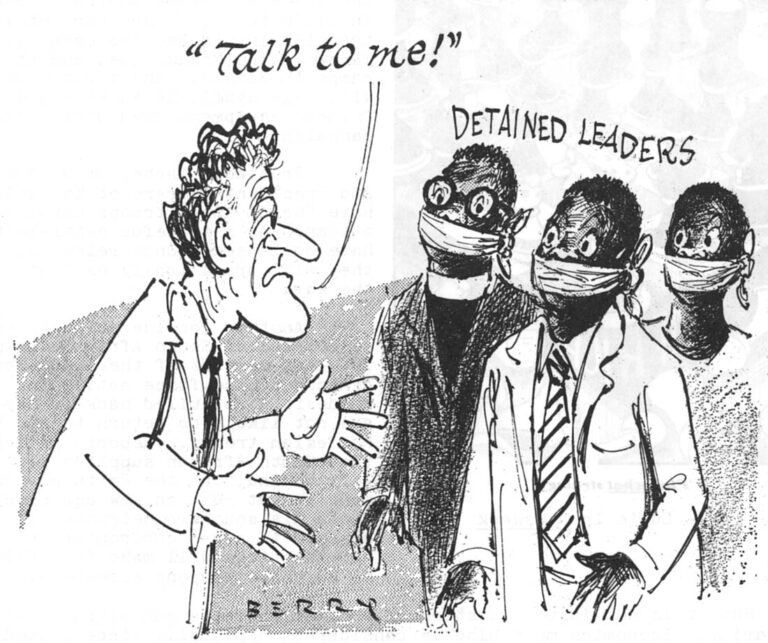

Mr. Smith first complicated this fourth settlement effort by declaring that certain exiled militants whom he labeled “terrorists” — would not be granted amnesty for the second or committee stage of negotiations to be held in Rhodesia. This meant that one-half of the ANC leadership could not participate. Over this issue, the talks collapsed despite the fact that there was agreement on all other general points.

Shortly after the collapse, the ANC split over leadership and strategy disputes, making external pressure on the Rhodesian government seem a waste of time. The moderate faction, which held the majority of support within the ANC executive committee, then called for a Congress in late September and elected its own man, Mr. Nkomo, the new president.

But this did not solve the problem. For while the moderates — once known as the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU)–have the backing of provincial leaders, the militants — once known as the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU)–have greater support at the grass roots level and among the young. Thus, the moderates have the leadership, but the militants have the loyalty of the guerrillas and future generations.

The external participants have the clout to pull the ANC factions together and to push Mr. Smith into a settlement, but the cost in both political and economic terms would be high — perhaps too high. Specifically:

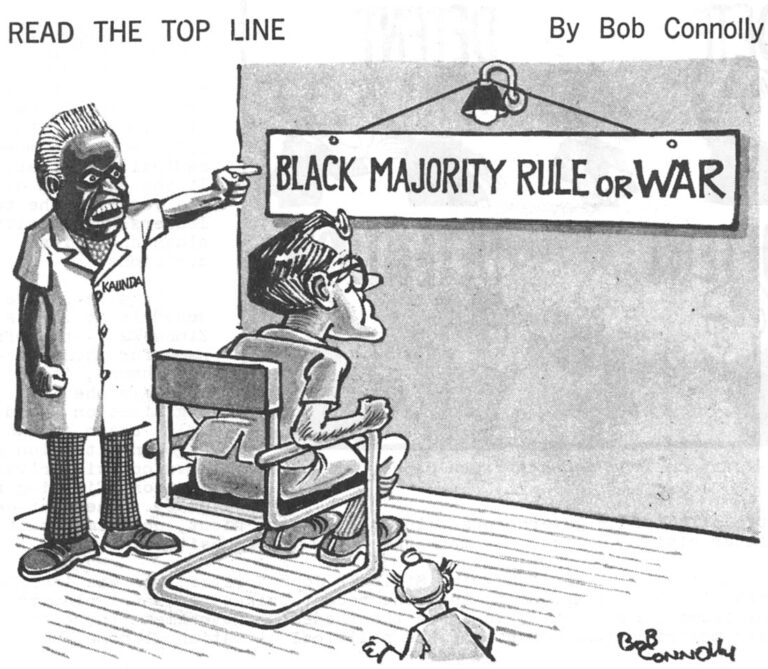

Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia and Botswana are all behind black majority rule, but they also desperately want peace for economic reasons. As Zambia President Kenneth Kaunda said, backing a guerrilla war would drain his country’s economy and resources. The same is true in the other three nations, especially Mozambique. So while ideologically they support any extreme to get universal suffrage, they want a peaceful settlement for pragmatic reasons.

The governments may also fear that pushing the four black nationalist factions together, as they were able to do last December, would not last.

The deepest split, between ZANU and ZAPU, is long standing, triggered by the break of the Rev. Ndabaningi Sithole from ZAPU in 1963 to form a more radical organization. It has deepened over the years by the two leaders’ personality clash and tribal divisions.

Rival ANC leaders:

If a re-united ANC moved in to form a Zimbabwe — the African name for Rhodesia — government, it is possible the organization would then split again, and an Angolan situation would develop, with rival factions fighting for power. The cost-benefit ratio of the four governments using their joint clout, only to result in a later civil conflict, has made the governments hesitate.

As for South African Prime Minister John Vorster, who was instrumental in pushing Mr. Smith into the recent talks, he cannot play the many trump cards that would force the Rhodesian government to accept black majority rule because of the political situation at home.

His electorate is devoted to supporting the white Rhodesian population, thus the South African leader fears any “radical” action would lose support for his National Party and perhaps even cost him the premiership to the many figures who are waiting in the wings for his detente exercise to fail, or at least stumble.

Thus the external parties want the action to at least go one step further within the country. The talks broke down at Victoria Falls over an artificial issue without ever confronting the crux of the crisis: the role of the 5.8 million blacks.

Observers feel dialogue between the white government and the newly-elected moderate black leaders will resume in October to take up the meat of the matter. A deadline of Oct. 31 was suggested at Victoria Falls and there remains some feeling that it should be the target date for results — one way or the other.

Both black and white leaders in Rhodesia suggest that terms can be reached. But if the current positions are maintained, it is clear that a settlement will not be made peacefully.

Mr. Smith will certainly attempt to sell “paper rights” to black nationalists in a new constitution perhaps a few cabinet posts, greater but not universal suffrage, lifting certain restrictions, increasing civil servant positions, etc.

But despite a recent interview in which the Prime Minister mentioned the possibility of a black prime minister “someday, if qualified,” political observers feel this in no way indicates that he will ever “succumb” to a black government “now.”

Mr. Smith may hope he can convince Mr. Nkomo to accept less on grounds that the black nationalist would be the chief office holder among African representatives. This would ensure his leadership against any challenges from Rev. Sithole.

Mr. Smith may hope he can convince Mr. Nkomo to accept less on grounds that the black nationalist would be the chief office holder among African representatives. This would ensure his leadership against any challenges from Rev. Sithole.

But despite his reputation as a moderate, Mr. Nkomo has as yet shown no signs of buying anything less than the militants would. The former ZAPU chief has already rejected several proposals, including the former South African scheme which would give the franchise to any African having completed at least one year of secondary school. This would be put into effect at elections held within one year, with the possibility of one-man, one-vote thereafter.

According to government statistics, more than 64,000 blacks would qualify for the vote under this program — as opposed to over 84,000 whites now registered. The nationalists have turned down this option because it would still leave them at the mercy of the white electorate.

If resumed talks break down, Rhodesia must then face the other alternative: war. The feeling that the government is not willing to settle peacefully at any cost is reflected in the fact that it has recently beefed up its armed forces by cutting back the deferment period for immigrants and college students, enlisting women, hiring more foreign “volunteers,” and lengthening reserve stints. On Sept. 12 every white, Asian, and Colored (mulatto — no black) between the ages of 25 and 38 was drafted.

The government appears to feel it can withstand a “terrorist campaign.” There has been guerrilla activity on Rhodesia’s northeast border since 1972, but the casualties on the Rhodesian side have been small (55 Rhodesians, 17 South Africans) in comparison with the insurgents (634).

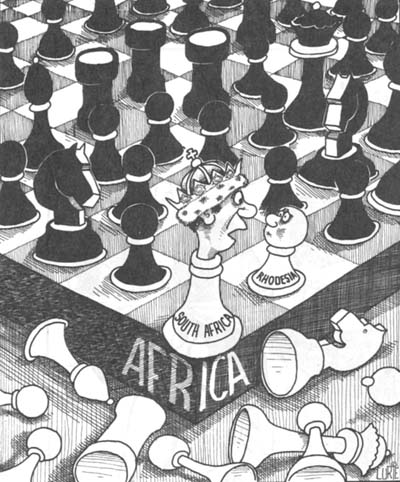

“We are like Israel fighting against the massive Arab world,” one official commented. “Even with several surrounding countries against us we can successfully defend ourselves. Our forces are bigger than theirs (13,000:9,000 estimated) and better trained.”

“The guerrillas may be encouraged by what happened in Mozambique (where Frelimo fought a ten-year war against Portuguese troops) but they must remember that Frelimo never won that war. It was the Portuguese soldiers giving up that led to a new, black government. There’s a difference here — the whites will never give up.”

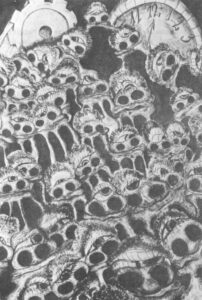

But the recent small-scale guerrilla effort does not reflect the level of future confrontations. An estimated 9,000 are currently training in old Frelimo camps in Tanzania and Mozambique, and at ANC camps in Zambia. And Mozambique will make available Russian and Chinese equipment used during its campaign.

President Machel of Mozambique and President Nyerere of Tanzania have “held” these troops until all attempts at a peaceful settlement have collapsed. Once released, they will dramatically escalate the war.

Another consideration is the withdrawal of South African troops. The last members of the 2,000 South African police force active in Rhodesia were pulled back in May and are not likely to return to aid the Rhodesian troops. Reports indicate that South African supplies were left behind, but the Smith government cannot rely on new equipment since his southern neighbor is opposed to armed confrontation and sanctions will make it difficult to purchase weapons elsewhere.

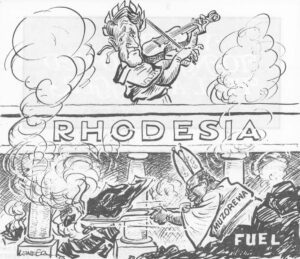

But it is not just a question of whether Rhodesia can stand a war militarily. Economics must also be considered, especially since United Nations-imposed sanctions have already crippled the country. In fact, the economic factor could have the greatest impact on the outcome.

The northern border area — site of current fighting — is largely farmland and vital to Rhodesia’s agricultural production, since sanctions force the country to be largely self-sufficient. Increased guerrilla activity could eliminate cultivation of the area.

There has already been a slow-down in business due to the call up of new troops and reserves. Many offices are understaffed and unable to keep up with daily obligations. This will also become more severe as confrontation escalates.

The three black countries dominating Rhodesia’s border — all but a 130-mile stretch with South Africa — are among the countries urging majority rule and they could also make things difficult for Rhodesia economically. (See map page 3).

Analysts believe Mozambique would cut off business relations and make inaccessible vital rail and harbor facilities through which Rhodesia exports. Coal sent to Zaire via Zambia would end. And the rail line through Botswana to Cape Town (South Africa) would be cut off. This would virtually isolate Rhodesia except for a new single rail line through Beitbridge into South Africa.

But most important is the South African connection, which is Rhodesia’s only solid link with the outside world. Rhodesia’s currency is based on the South African rand. The majority of vital imports comes from South Africa, and Rhodesia in turn exports chiefly to Sou.th’Africa. South African investment and loans provide the basis for both public and private business — for those companies that are not South African branches to begin with. Without these sources the Rhodesian economy would collapse altogether. The economic links alone provide Mr. Vorster with enough trump cards to push Rhodesia in any direction it pleases.

But few observers believe a war would last long enough to let economic factors become the key. There is much speculation currently that outside forces would intervene after the war revealed its potential, to prevent further bloodshed.

Although Britain, since Rhodesia is technically still under its jurisdiction, and the UN are possibilities, most observers predict South African troops, with Zambian assistance, would be the ones to move in on the pretext of restoring order. Top South African officials have indicated in private that white bloodshed would provide the right political climate at home to justify intervention — on the grounds of saving the whites.

Although Britain, since Rhodesia is technically still under its jurisdiction, and the UN are possibilities, most observers predict South African troops, with Zambian assistance, would be the ones to move in on the pretext of restoring order. Top South African officials have indicated in private that white bloodshed would provide the right political climate at home to justify intervention — on the grounds of saving the whites.

The scenario on this possibility suggests that the joint South African-Zambian team would then install a black government as the only means of maintaining peace.

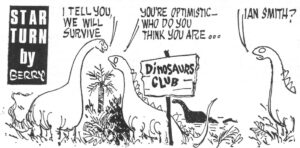

Thus the future facing Mr. Smith is grim. He does not want either alternative now confronting his country and his only hope — of reaching terms short of majority rule with the moderates — is not likely to be bought by the other parties that would have a final say on settlement terms.

As a leading political science professor at the University of Rhodesia pointed out, the issue has become so internationalized that it is not just the southern African countries that must be satisfied.

“It is apparent now that Britain would not accept much less than majority rule. Before recognition is granted, the House of Commons will debate the issue extensively and will have to be satisfied that Smith is no longer head of state. He represents continuing white supremacy, which they have ‘fought’ for a decade now, so they are not likely to accept any plan that would keep him in power.”

“Also, the UN must be considered. Before lifting sanctions it too would have to be satisfied that there was significant change.. The African block is significantly large to prevent any acceptance of something short of majority rule.”

“In light of these factors it is unlikely that any deal short of black majority rule could ever be successful, even if some local black leaders accepted it. Remember, even if one group of nationalists ‘sold out,’ there would still be a significant faction of blacks wanting immediate majority rule, and this would weigh heavily on the consciences of outside forces. No, I’d say Mr. Smith doesn’t have much longer.”

An editorial in South Africa’s Sunday Express summed up the sentiment of most observers: “The dismaying thing about Rhodesia is its consistent inability to read the writing on the wall…. It simply drifts along with an air of blind complacency that is as remarkable as it is disturbing.”

A former Rhodesian opposition MP declared, on the same note: “It is clear that Mr. Smith’s strategy is not the logic of a 22:1 ratio. The Rhodesian powder keg is about to blow up and this is a tragic waste because whichever course he chooses, the end result will be the same.”

Received in New York on October 6, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.