On November 11 the massive southwest African territory of Angola gained independence after 500 years of Portuguese colonial domination. But while the longest liberation struggle in black Africa has ended, the trouble is far from over. A bitter civil conflict among the three rival movements for complete control of the country prevents the factions from focusing attention on the many political and social problems of a new nation.

Most of the recent publicity has focused on the military situation — progress on the two fronts, goals of the factions, and the arms race. But Angola has many other problems to face as a new nation.

Robin Wright recently spent five weeks in Angola, visiting all three areas of the country. In the following report, Wright assesses some of the non-military troubles in Angola that spell a lonely and bleak future for this country, which was once considered an idyllic tropical haven capable of realizing vast wealth from mineral and agricultural resources and offering its population a good life.

Luanda, Angols

Just before sunset on November 10 the last Portuguese flag in Africa — flying from a romantic 16th century white fortress overlooking the Luanda harbor in Angola’s capital city — was quietly lowered by one representative of each of Portugal’s armed forces — a soldier, a sailor and an airman. High Commissioner, Admiral Leonel Cardoso and the few remaining Portuguese troops then drove under armed guard to the port and unobtrusively slipped away on seven ships bound for Lisbon.

Just before sunset on November 10 the last Portuguese flag in Africa — flying from a romantic 16th century white fortress overlooking the Luanda harbor in Angola’s capital city — was quietly lowered by one representative of each of Portugal’s armed forces — a soldier, a sailor and an airman. High Commissioner, Admiral Leonel Cardoso and the few remaining Portuguese troops then drove under armed guard to the port and unobtrusively slipped away on seven ships bound for Lisbon.

It was a low-key, private ceremony, an anti-climatic ending to nearly 500 years of colonial domination in this massive southwest African territory, an end which also terminated Portugal’s long presence on this continent.

There was none of the usual pomp of handing over the reins of power to a new government, nor any joint celebration of the birth of the world’s newest independent state. For there was no single united government to accept sovereignty on behalf of all the Angolan people.

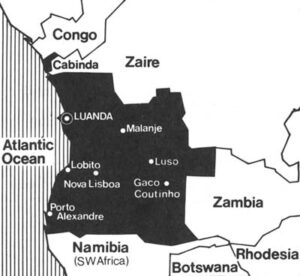

The scenic tropical territory — 14 times the size of Portugal — is currently torn by a bitter civil conflict between three rival movements: the Popular Liberation Movement (MPLA), the National Liberation Front (FNLA), and the Union for Total Independence (UNITA). All three fought the Portuguese during the 13-year liberation war, and each now claims the right to govern the country.

Although Portugal is unofficially sympathetic to the leftist MPLA, the increasingly tenuous military position of that faction and the delicate political situation led the High Commissioner to hand over sovereignty only to the “5.8 million people of Angola,” without naming any one movement.

In effect, the Portuguese surrendered, running from a problem they could not solve. Angola is now left on its own to sort out the many problems of a new nation, and to decide — militarily or politically — who will administer the state.

The problems the Portuguese left behind are so immense they have yet to be evaluated completely. And they are not just military or administrative.

Before the Portuguese transition government pulled out on November 10, an estimated 250,000 Portuguese civilians fled Angola, mainly for Brazil or Portugal, on refugee flights offered by some dozen nations and international organizations. Many others exited illegally, leaving only a few thousand whites to run the businesses, industries, agricultural estates and social services they controlled during the colonial era. The result is an immense void at all levels of management.

Administratively, Angola is now left without an effective government. The three rival movements have formed two separate states: the Soviet and eastern bloc-backed MPLA declared Dr. Agostinho Neto president of the Peoples Republic of Angola, based in the traditional capital of Luanda. The recently-merged centrist FNLA and socialist UNITA movements declared a joint government as the new Peoples Democratic Republic based in Huambo, formerly Nova Lisboa.

Neither of the two administrations has the funds, organization or experience required to lead a new nation. And the military effort has distracted both from planning adequate programs for the future. Angola, in effect, is at a standstill while the war monopolizes the attention and resources of the rival factions.

The MPLA talks vaguely of “studies” on issues of national concern, but it has not yet channeled its socialist ideology into concrete efforts. UNITA has long struggled with meeting just the requirements of daily life since it has historically had the fewest foreign backers to provide funds and aid. So, while it has a definite socialist platform — one more moderate than the MPLA’s — it has not the personnel or time to formulate plans.

The situation was complicated by Portugal’s reluctance to negotiate during the transition. Unlike the lengthy and detailed meetings to organize the transfer of power in its two other African possessions (Mozambique, which became independent on June 25, and Guinea-Bissau on September 11, 1974), Portugal waited until the last minute to deal with the logistics of handing ever the reins of power — replacement and training of civil servants; transfer of banks and Lisbon-based company branches; operation of the ports, airports, military facilities and communication stations. There were no arrangements for foreign aid or temporary assistance from Portuguese professionals or technicians to replace those who fled.

In explaining the situation just a few days before his departure, Admiral Cardoso said negotiations had been started in October, but mainly “out of desperation.” Things have to be run after we leave so we have no alternative but to talk with the people who are running the area. In Luanda it happens to be the MPLA, so we are now negotiating with them.

“There is much, too much, left to be discussed. Their attention is often diverted from administrative concerns by the military situation. I don’t think they are aware of what and how much still has to be done.

“But we are helpless to do more right now. We still hope for a reconciliation after which we can deal with the transfer of operations throughout the country to a single united government.”

However, the last-ditch reconciliation efforts by both the Portuguese and the Organization of African Unity proved — not surprisingly — fruitless and there are now more stray ends than those tied up.

There are physical signs throughout the country of the problems Angola now faces. In Luanda, the bustling hum of the capital’s industrial zone is hauntingly absent. Traffic only dribbles down potholed streets. It is difficult to get garbage collected off the city’s bougainvillea-lined boulevards or to find essentials in the few stores still open.

In Nova Lisboa, Angola’s second largest city and second capital, water and electricity are available only a few hours each day. All commodities of food are scarce. With only 40 whites left of the 100,000-plus European population, most homes have been abandoned and most businesses boarded up or barred.

Life for the average African has become a burden. Unemployment is at an unprecedented high since many businesses have closed and the main source of domestic labor was all but eliminated with the exodus of the Portuguese.

Blacks living in the muceques — poor suburbs — sit idle with no income. And food is difficult to obtain, if there is money for it. “My family and my neighbors are down to one meal a day and none on Sundays,” a former industrial worker in Gika muceque of Luanda lamented. “I have nothing to do, no place to go, no money. I am for the MPLA, but I cannot fight if I am starving.”

Harvesting of crops has been difficult lately because of intensified fighting and the draining of manpower by the armed forces. Coffee crops, for example, are down by over 50 percent. People now are living off last season’s harvest. But the next six months will e increasingly difficult in all three areas. Famine is already a reality in the North, despite United Nations and Red Cross efforts to supply food and aid.

The average Angolan is also without the social services provided by the Portuguese system. There are fewer than 100 qualified doctors left to serve a 5.8 million population and few hospitals are operating. When a member of the Portuguese High Commission had a toothache, the staff could not find a single dentist in Luanda, so he had to be shipped to Lisbon.

Education is another problem. Portuguese staffs in urban centers have withdrawn, and most of the mission schools, which provided the main means of education, have closed. With about 90 percent of the population illiterate, education should be a primary concern of all three movements. But at the moment any minimally qualified adult is being used in the respective administrations.

“We just don’t have the personnel to run all the schools left by the Portuguese, much less set up new facilities for the many who need schooling,” a UNITA official in Huambo explained. “We keep hoping that more of the Angolans studying abroad will come home to help relieve us, but they want to finish their educations. Unfortunately, it’s one of the many by-products of the war.”

Several thousand Angolans also face the problem of being homeless. Many small cities and villages have been destroyed by the war. At Caxito, where FNLA and MPLA forces battled for weeks, there are few buildings left standing. All inhabitants had to flee.

And in many of the southern coastal villages recently taken by the joint UNITA-FNLA “flying columm,” residents were evacuated in advance to prevent bloodshed. Rehabilitating then is a serious problem, again for which the movements have neither adequate resources nor personnel to handle.

But by far the gravest — and perhaps most ironic — single problem facing independent Angola is the economic situation. Historically Angola has been one of the few countries in Africa that could pay for itself — and have enough left over to ease the endemic poverty of Portugal and its other possessions. In 1972 the U.S. State Department said Angola had a 108 million dollar balance of payments surplus. Other diplomatic sources say it was ever 300 million dollars in 1974.

But when the Portuguese left, there were few trained blacks to take over; in most cases the Angolan population is simply unfamiliar with the systems and structures they are now expected to operate. According to Luis de Almeida, MPLA director of information, “Only ten percent of the black population has had a share in the business and industry of this country — and that includes laborers.”

As a result, Angola, potentially one of the wealthiest nations in Africa, will suffer for years because of an inability to use existing avenues to income, much less undertake new economic development. The assets are abundant:

The northern oil-rich Cabinda enclave is considered by some experts to have greater resources than Kuwait. Over 54 million barrels of oil were produced in 1974, making it the principal export commodity. Angola is the world’s third largest coffee producer. There is vast wealth in diamonds, copper, manganese, iron-ore, gold, bauxite and platinum. And the south is one of the richest agricultural belts in Africa, principally producing timber, wheat, sugar and maize.

But the war prevents development and attention to these economic assets. Many interested foreign investors have been scared off, and most of the Portuguese management of existing companies have left.

As one banker explained: “Only the surface of Angola’s wealth has been scratched. But if anyone came to me to invest substantially in Angola, I’d tell him he’s crazy. Eventually the country may settle down and prosper. But in the short term the economy simply must get worse because of politics.”

Production of most export commodities is down to 20 percent, and steadily declining. A survey by the Industrial Association of Angola earlier in 1975 also showed that markets were dwindling, costs soaring and raw materials in short supply.

And those products that are ready for shipment cannot get beyond the harbor because of a slowdown from labor troubles. The recent fighting around the southern parts of Lobito, Mocamedes and Novo Redondo has cut off the use of those ports altogether. On August 10 the main railway line was also cut off because of fighting.

The situation is so grave that, as another banker explained just before leaving for a new home in Lisbon, “If it were not for the reasonable amount of foreign currency earned from Cabinda’s oil, our economy would be instantly strangled. The Angolan economy generally is treading water and all that remains is for the plug to be pulled.”

There is no phase of life left unaffected by Angola’s bitter civil conflict. The cost to this once idyllic tropical haven will be high, observers agree, taking years to get back to the level of life before the war began in early 1975 and two or three decades to realize the benefits of its wealth.

At this point, the winner of the war is still in doubt. But it is clear already who are the losers — the Angolan people.

Received in New York on December 12, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.