Behind the bitter civil conflict that currently divides Angola into three zones of influence and two separate governments are three men: Dr. Agostinho Neto of the Popular Liberation Movement (MPLA), Dr. Jonas Savimbi of the Union for Total Independence (UNITA), and Holden Roberto of the National Liberation Front (FNLA).

Dr. Neto is president of the Peoples Republic of Angola, based in the vast and central areas of the country. Dr. Savimbi and Mr. Roberto have formed an uneasy alliance in a joint government as the Peoples Democratic Republic, covering the northern and southern territories. Both governments claim to “truly represent all the people of Angola.”

Robin Wright recently spent five weeks in Angola and had an opportunity to meet each leader in his home base during a tour with the Conciliatory Commission or the Organization of African Unity. The report that follows is an assessment of these three distinct and disparate personalities.

Dr. Agostinho Neto: Popular Liberation Movement (MPLA)

Luanda, Angola

Dr. Agostinho Neto has all the proper credentials for an African liberation leader — intellectual, guerrilla fighter and “prison graduate.” His varied career is spiced with experiences reflecting these diverse qualifications: a soft-spoken poet of protest, a physician who was arrested in front of his patients, and an exiled politician who came back into Angola carrying a machine gun to fight against the Portuguese.

A dignified, portly, almost professorial looking man, the 53-year-old leader of the MPLA is the best qualified man of the three leaders to run a newly independent country, politics aside.

A dignified, portly, almost professorial looking man, the 53-year-old leader of the MPLA is the best qualified man of the three leaders to run a newly independent country, politics aside.

Yet his quiet style may be a drawback, especially among a people — as in all Africa — where the fiery oratory of a demonstration is the main means of rallying support.

Addressing a crowd, Dr. Neto is a serious and sincere speaker, perhaps a little too technical for the masses. Many of his aides and ministers are better at eliciting cries of “the struggle continues” and “victory is certain.”

The MPLA leader is better in small clusters of officials or one-on-one, at dialogue and political discussions, which may explain why he is not as visible as other figures in the movement.

He comes on strong in private, especially about the alleged Marxist-Leninist leanings of the MPLA. “I totally reject the accusation that our movement is inspired by Marx or ruled by any outside force. When they ask about our ideology, we say we are progressives interested in real democracy, especially for the exploited man. We are interested in social reforms, in economic democracy.”

The MPLA is fortunate in that there are many skilled spokesmen and officials to maintain the momentum required in a “liberation” struggle. Initially an underground movement of better educated mesticos (mulattos), the MPLA attracted early intellectuals and urban-dwellers who had been trained in Portuguese-run schools or abroad. As a result, the Popular Movement has by far the highest number of skilled personnel to run an administration.

Dr. Neto, however, remains the figurehead in the heart of the masses. His picture in huge dimensions is visible on posters plastered on stores and homes throughout Luanda. And MPLA buttons and medallions are mainly miniatures of his bespectacled face.

The amiable leader has been a rallying figure for the liberation movement since his university days in Lisbon, when his poems of protest inspired other nationalists to the point he was arrested by Portuguese officials and jailed in the mid-1950s. A sample:

Realization

Fear in the air!

On each street corner

Vigilant sentries light incendiary glances

in each house

hasty replacement of the old bolts

of the doors

and in each conscience

seethes the fear of listening to itself

History is to be told

Anew

Fear in the air!It happens that I

humble man still more humble in my black skin

come back to Africa

to myself

with dry eyes.

After finishing his medical studies in the late 1950s, Dr. Neto returned to Angola, but only to face a repeat of the trouble in Portugal. In June 1960 he was arrested in his consulting room in front of patients. Villagers who went to protest his detention were fired on by police, killing 30 and injuring over 200.

Deported to a jail in Cape Verde for three months, then imprisoned in Portugal for nine months, he gained international prominence after his daring escape in mid-1962 to Morocco. From that point on, Dr. Neto became inseparable from the liberation movement. At the MPLA’s first national conference in Kinshasa in December, 1962 — just five months after his escape — he was elected president.

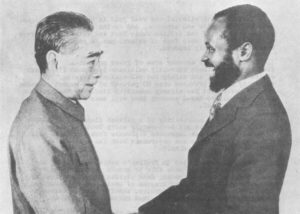

Dr. Neto, member of the Mbundu tribe of central Angola, has traveled extensively as a revolutionary leader — receiving invitations from the Vatican, Peking, Moscow and countries throughout Africa. He has now reached a position he is obviously not willing to relinquish. His rivalry with the other movements has become a personal one, especially with Mr. Roberto, proven by the fact that he has not been interested in maintaining any of the many reconciliation agreements signed with the FNLA and UNITA.

He is uncompromising about the MPLA’s militantly socialist platform, according to aides, and thus any alliance with the other two movements is unrealistic. “They are not truly representative of the Angolan people,” Dr. Neto says often.

“Their military relies on reactionary South African forces,” he told the OAU, “They could not make any progress without them. They have more people than we do in their territories, but they still turn to outsiders. Where is the support of the people?”

“Until the OAU and the United Nations unequivocally condemn the foreign invasion, we will never accept the intervention of these organizations which effectively are helping neo-colonialism in our country.”

But despite Dr. Neto’s hard line, many foreign diplomats and political observers believe he is in political trouble and will eventually be replaced.

“After the military situation is settled, or perhaps even because the MPLA is falling back, Neto will be dumped for a fresher figure. The Revolta Activa (a dissident group within the MPLA started by the Andrade brothers) is quietly getting stronger. They may take control of the party, or else elements in the mainline will react to the dissenters by putting in a new president,” one knowledgeable foreign source explained. It remains unclear, however, who would replace him.

It appears more likely at this stage that the bitter civil conflict that rages in Angola will keep Dr. Neto in power. While the MPLA is dependent on Soviet, Cuban and other socialist sources to back their war effort, his links with these allies gives him enough leverage to stay in power.

But should a political settlement be negotiated, Dr. Neto would be too militant and too representative of the MPLA old guard to be acceptable as a possible chief of state. An MPLA military victory, allowing time for attention to political debate within the movement, would also put his future in doubt.

Dr. Jonas Savimbi: Union For The Total Independence of Angola (UNITA)

Silva Porto, Angola

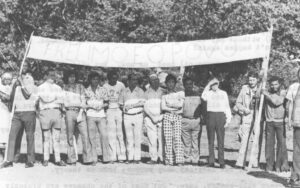

Walking towards the thronging crowd awaiting his arrival, Jonas Savimbi oozed with charm and warmth. Smiling, waving, he worked his way through the mobs, shaking many outstretched arms, to the stairs of the platform from which he was to speak.

The occasion was the presentation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Conciliatory Commission to the people of southern Angola, but the charismatic Savimbi was the only real focus of attention.

The occasion was the presentation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Conciliatory Commission to the people of southern Angola, but the charismatic Savimbi was the only real focus of attention.

“Sa-VIM-bi, Sa-VIM-bi,” the crowd chanted. Another smile, another wave. “Sa-VIM-bi, Sa-VIM-bi,” the roar went up louder.

In his fiery oratory style Dr. Savimbi started to address the 100,000-strong audience. But he had to stop. Chants of “Sa-VIM-bi, Sa-VIM-bi” continued to drown out the public address system.

Of the three Angolan liberation leaders, the handsome, 41-year-old UNITA chief is clearly the most popular among his people. As one American-educated aide suggested with pride: “He is Angola’s John F. Kennedy.” To many, Dr. Savimbi is UNITA.

But that is fact as well as a product of his character. Dr. Savimbi founded UNITA in 1966 after a longstanding feud with the FNLA’s Holden Roberto finally forced him to leave that organization. At an OAU meeting in Cairo in 1964 Dr. Savimbi, then FNLA Foreign Minister, announced his resignation and accused Mr. Roberto of “flagrant tribalism,” and corruption. He alleged that Mr. Roberto had set up a “commercial empire in the Congo” (now Zaire) and that FNLA administrators were “wage earners and profiteers who enriched themselves on the money of New York financial circles and other international organizations.”

Within two years, Dr. Savimbi built up his first meager, 12-man force into a sizeable army, gaining popularity and support as the only leader to work within the country alongside his men in battle against the Portuguese.

“Leaders must fight alongside the people and not stay abroad, sending ‘second-class’ fighters to face the Portuguese,” he explained.

The bearded leader mixes often and easily with the people as well as the military. He is accessible to the point that his aides lament the awaiting workloads that may not be handled that day.

He is as concerned about the availability of scarce foodstuffs as he is on arms. “This is not just a war between soldiers. We are fighting for all the people, to ensure a better -way of life. We must consider their needs too,” he commented during an encounter in Silva Porto.

Dr. Savimbi is perhaps too involved with small matters, critics charge. He does not delegate enough authority and a weak bureaucracy is one of the reasons for UNITA’s poor showing in the past.

But there may be no alternative for the Swiss-educated, Chinese-trained leader, for finding skilled personnel is difficult in his stronghold in southern Angola. Among the Ovimbundu, the rural tribe that dominates the South, the only means of education during the Portuguese era were a few protestant mission schools. Most are farmers and have little time or interest in formal education. Thus at an administrative level there are few qualified to share the burden.

As a result, Dr. Savimbi is the chief politician and military leader. When journalists need answers to questions on either matter he is the only source. But he is extremely cooperative with the press, especially in comparison with the abrasive Roberto and the reticent Neto.

“Welcome. Have a seat,” he greets reporters in either fluent English, French or Portuguese. “What would you like to discuss — the war, our platform, our people?” He sits back and smiles, waiting for the onslaught of questions he answers constantly.

How would he describe the politics of UNITA?

“I am not communist because it serves no purpose. Nor am I a capitalist. Socialism in this country is the only answer. Those who led the country to independence cannot become the exploiters of the people. We want a socialist system, but which? There is the orthodox one and the extremist one. We want the democratic one, social democracy.”

What about the role of foreign companies, necessary for the development of Angola’s vast reserve of minerals?

“I am against nationalization; it is a disease which saps the strength of a national economy. The real question is the renegotiation of allowable profits. Foreign companies need their profits, they would not invest without them. But the people of Angola need their share. When Angola is independent the investors must know that the people will have a greater share.”

What about economic cooperation with South Africa? Can the two countries coexist peacefully?

“We support completely the atmosphere of detente. There is a need to live together peacefully in this area, that is a must. That is why we back completely the initiatives of Presidents Kaunda, Nyerere and Seretse Khama. Prime Minister Vorster is an intelligent leader and he must know that the independence of Angola will have an effect on South Africa.”

“I hope the future leader of this country will be realistic. We have a dam at Cunene (a power source for South Africa). We have investments involving South Africa. Should we ostracize them? I hope that a leader here will be realistic enough to cooperate with any country despite differences in political systems.”

What is your evaluation of the current military situation?

“Since October the war has changed. We are no longer fighting only the MPLA, but also the Cubans. The MPLA used to run when fired on, but the Cubans held out under fire. Since then the real war has begun.

Is there another solution possible to the Angolan crisis other than a military victory by one side?

“I think there can be only a political solution. No military solution is realistic. In the past the MPLA conquered 11 of the 16 district capitals in Angola. Now we have retaken them and more. But this cannot go on forever. They take cities and lose cities and so do we. The result is only a disastrous loss of life and the total ruin of the country.”

“Only elections — free elections — under OAU control can provide a final solution. But first there will have to be a short period of transitional government in which both sides would be represented. But in the end, the ballot must decide, not bullets.”

What about the alleged presence of foreign troops in the South?

“We have white specialists, but not necessarily mercenaries or South Africans. Obviously our white Angolan brothers are also fighting in our ranks. Let me tell you that after the Soviet and Cuban intervention on the MPLA side, the MPLA are not entitled to criticize us for whatever outside help we may obtain.”

This is one question that draws a rare show of anger from the normally soft-spoken man, and he ends the interview on that note. Later he apologizes for his abruptness and says “It is a touchy matter and the MPLA is lodging vicious charges against us. We are sensitive about it.”

But the alliance with South Africa — officially or unofficially is well known. Several sources claim that Dr. Savimbi was in South Africa briefly on Nov. 10, a day before independence, although the purpose of his mission is unknown.

The need for such an alliance is pragmatic since UNITA has traditionally had the fewest outside sources for aid, funds and military equipment. The merger with the FNLA has provided a new source of weapons; during the OAU stop in Silva Porto, two Air Zaire planes were offloading large crates — no passengers — at the local airstrip. But this dependence puts UNITA in a weak position in the merger and Dr. Savimbi would surely prefer to have his own contacts in case the uneasy alliance breaks down. South Africa, with many investments in southern Angola, is a natural source.

Dr. Savimbi was quoted recently as saying: “If Holden had been as open-minded in 1964 as he is now I would never have left him. He how appreciates Angola’s needs.”

But political observers think it is a most unnatural relationship that wll collapse, either after a victory over the MPLA, or after the new joint government has had time to factionalize.

There are already reports that the UNITA-FNLA union almost collapsed during negotiations on positions in the new government in Kinshasa, at which the FNLA initially insisted that it be given the key ministries. And in Lusaka, UNITA officials would not recognize the FNLA credentials held by journalists trying to get into the South.

For Dr. Savimbi to continue to play a key role in the war, he must have some bargaining power. The fact that the Ovimbundu, the largest single Angolan tribe, could win a plurality in an election offers him a limited degree of leverage, as does his political position in between the militantly socialist MPLA and the centrist FNLA. But a foreign source of support — in this war now led, fought and financed by outsiders on all sides — gives him the edge he needs.

UNITA could not be ignored in any political settlement, but while the future still appears to depend on a military victory, Dr. Savimbi is practical enough to know he must have the cards in the meantime to stay in the game.

The UNITA leader — strong, determined and still idealistic — remains a dark horse. But in the bitter civil conflict in which Mr. Roberto and Dr. Neto are irreconcilable enemies, Dr. Savimbi may be the only compromise satisfactory in either a political or military settlement.

Holden Roberto: National Liberation Front (FNLA)

Ampriz, Angola

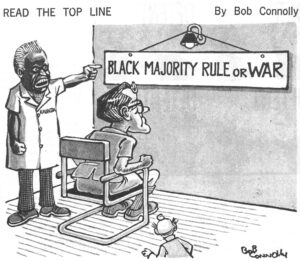

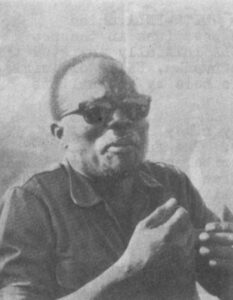

In contrast to his UNITA counterpart, Holden Roberto is a hard, introverted man, appearing almost sinister under his ever-present dark glasses, worn even in dark rooms or on a cloudy day. He is blunt and often abrasive, spending most of his time huddling with his tight groups of aides and ministers, rarely “wasting time” on public appearances. Reporters joke about the glare felt even from behind his glasses.

During the afternoon he spent with the OAU, Mr. Roberto made no effort to sweet talk the Commission. In his “welcoming” address he declared: “The Angolan problem must be settled by the Angolan people. We do not need the assistance of negotiators outside this country, not even those in Africa.”

During the afternoon he spent with the OAU, Mr. Roberto made no effort to sweet talk the Commission. In his “welcoming” address he declared: “The Angolan problem must be settled by the Angolan people. We do not need the assistance of negotiators outside this country, not even those in Africa.”

During a brief personal encounter with the trim, 53-year-old FNLA leader, this reporter found him to be almost hostile. I encountered him, dressed in fatigues, strolling alone up and down the empty reception room where he was to meet the OAU officials. Guards said he had been there, alone, for the past two hours awaiting the delayed Commission.

I approached and identified myself as an American journalist who wanted to talk briefly before the OAU arrived. “I’m busy, can’t you see?” he said angrily. “Who do you think you are? Can’t you wait until the others arrive?

I attempted to plead the case of American interests, which drew only anger. “We are fighting for Angolans, not Americans. The people of Angola are my only concern, not the Americans.”

The conversation went on for about 20 minutes in the same vein, at which point I acknowledged defeat and asked if I could at least get some photos of him alone. “No, get out.” And then to a guard, “Get this woman out until the OAU arrives.” And I was summarily escorted from the empty banquet room.

Mr. Roberto’s straightforward style may be the result of the long and hard haul as Angola’s first modern liberation leader. It has been a difficult period, spotted by intra-organization feuds and splits, and the problems of obtaining aid and arms.

First to establish a government-in-exile, Mr. Roberto is considered more of an administrator than a military commander, despite the increase in time spent on the northern front in recent weeks.

Critics charge that his prime interest in Angola is not political, but economic. They point to the fact that he left Angola for Zaire at the age of two and has spent more time outside than inside the country. As a result, his Portuguese is weaker than his French and English.

But there is no doubt that he is the leader of the militant Bakongo, the northeast tribe that dominates the FNLA. In fact, his first political alliance was with Uniao das Populacoes de Angola (UPA), which wanted to restore the ancient Kongo kingdom in a country separate from both other Angolans and the Portuguese.

It was only after a trip to the All-African Peoples’ Conference in Ghana in 1958 that he abandoned tribal politics and helped broaden the movement into a liberation struggle against the Portuguese.

Although it was the MPLA that launched the first assault against the colonial regime on February 4, 1961, it was the UPA that made the first major attack in March. The fiery-tongued Roberto rallied his young militants in the underground movement for the attack, which led to the deaths of an estimated 750 Portuguese and 20,OOO Africans. After the fighting some 150,000 Bakongo fled to Zaire, many of them joining Mr. Roberto’s ranks.

The following year Mr. Roberto negotiated the merger of UPA with the Partido Democratico de Angola for the birth of the FNLA, over which he reigned supreme until an attempted overthrow in 1965-66 prompted him to turn temporarily to business and property interests in Kinshasa.

A boost from Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko, a distantly related in-law, and new aid from the United States and China in the early 1970s encouraged him to focus full attention again on the liberation struggle. During the last years of the liberation struggle he became the leading opponent of the Portuguese.

Reporters find the FNLA chief a reluctant interviewee, at best. He does not like to talk politics and lists the movement’s objectives simply as: “land reform, education and economic development.” He prefers to have FNLA Minister of Information, Hendrick Vaal Neto, or his American-educated aide, Paul Tuba, do the talking for him.

Unlike Dr. Savimbi, Mr. Roberto pulls the strings from outside Angola, at his base in Kinshasa. He has only recently begun flying into Carmona, the FNLA headquarters in Angola, or Ampriz regularly. For his session with the OAU in Ampriz he spent only the afternoon, scurrying back to Zaire as soon as the meeting was over.

The son of a Baptist missionary, Mr. Roberto’s style is firm and authoritative, reflecting his upbringing. Part of the session in Ampriz was spent displaying Russian 122mm rockets seized from the MPLA on the northern front.

“Look,” he said to the Commission angrily, “These are the weapons used by the MPLA — Russian rockets. They fired 400 of them against our troops two days ago. How can anyone say the MPLA represents the Angolan people? It is a communist organization supported by the Soviets and they have no right to claim any part of this country.”

He then pulled out a 12-year-old boy, an MPLA prisoner-of-war, captured during the same skirmish. “Do you see what they have to resort to to fight us — children. They don’t have the backing of the people so they bring in small children. How can anyone ask such a small boy to fight?” he demanded, glowering.

Mr. Roberto obviously is not out to win friends, just a war. His approach, however, has led to several reports that he is in political trouble within his movement and that Daniel Chipenda, the former MPLA commander who switched sides in 1974, and N’Gola Kabangu, the FNLA Prime Minister, are out to unseat him. But it is difficult to tell just how deep the division goes.

However, at this point, it seems clear that Mr. Roberto’s only means of achieving his long-time goal of leading an independent Angola wll be through a military victory. His tribal backing does not represent a large enough segment of the population to win an election, and the long-standing feud with the MPLA would make his presence in any alliance, resulting from a political settlement, unfeasible. In the long term, the chances of Mr. Roberto achieving his goal look slim.

Received in New York on December 12, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.