Anchorage, Alaska July 17, 1972

For well over two centuries the artistic accomplishment of the Indians of the Pacific Northwest Coast has astonished all who have experienced it. Russians, Englishmen, Frenchmen, Spaniards and Yankee merchant mariners visited Alaska and the adjacent coastal islands to explore and trade among these unusual people. All of the visitors who were sufficiently literate to record their experience registered also their intellectual and emotional responses to the all-prevading creative production of this unique coastal culture….

The white man discovered Alaska and the coast at a period when the culture of the Indian flourished. He watched it come to full flower, and in his way, plucked the seed to see the culture diminish. Today the art expressions of the culture are scattered over the world and only in recent years have become desirable items for art collectors and museums of art.

Through the process of acculturation, the vigor of the native is being redirected. During this period of transition the emotional and personal stimuli to continue the traditional arts have died. The original motivation, cultural, communal and personal, has disappeared – the art heritage of the Alaskan Indian as an active process is lost.

Leon Gordon Miller 1967

Lost Heritage of Alaska

“I can remember when I first realized what a Tlingit Indian was. I began reading all these fantastic books on Tlingits and all of a sudden it dawned on me that, my God, that’s what I am! And what happened? What happened to this beautiful, beautiful trip?”

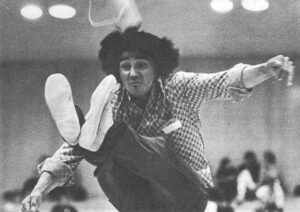

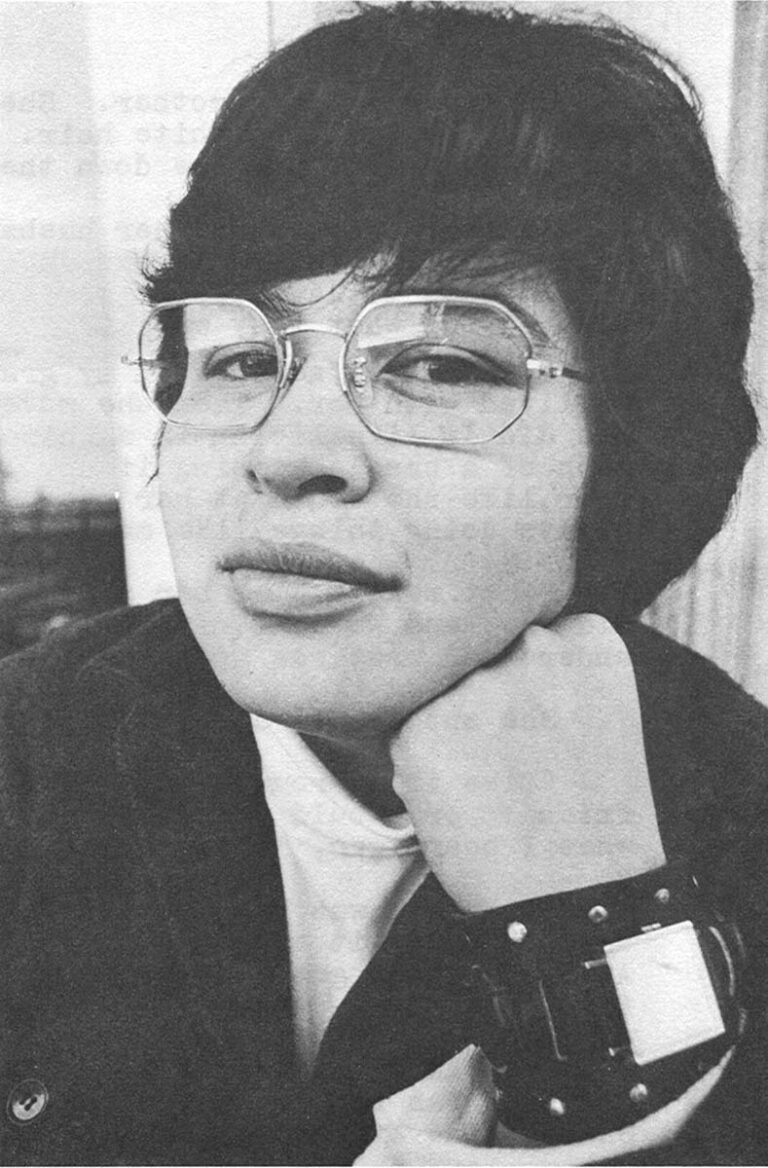

Artist Shanon Gallant, 24, sips her Scotch and ponders.

“Here I am from a race of people that was really a great people at one time…a recent time. To look at us now you’d never know it.

“Where were their heads when all this happened?”

This the prelude to a debate. RESOLVE: Whether to be known as an Indian artist or an artist who just happens to be Indian?

It’s not Just Shanon’s debate but one that confronts most of her Indian contemporaries. It’s a choice with little precedent because until a few years ago there was no option.

“Then Indian art was a tourist trip,” she recalls. “Something you bought in a gift store. And it was under a certain price.

“But over the last 20 years something has happened to American Indian Art. I think it’s more exciting than the plastics.”

Gallant is an award winning artist, potter and sculptor. Some critics think she’s where it’s at and it’s not surprising that her own life parallels the art transition of which she speaks.

At Odds

She entered the world at odds-born in Tlingit country in Southeastern Alaska and raised in the prodominantly white city of Juneau, the state capital.

She entered the world at odds-born in Tlingit country in Southeastern Alaska and raised in the prodominantly white city of Juneau, the state capital.

“I was raised by a super traditional Tlingit grandmother and a white father who was a Harvard grad. It was impossible to please them both.”

Formal integration came early.

“That’s the polite word for it. I guess I was about five or six. It was a really horrendous day. It was like they had a special bus for us. They told us we were going to be going to school with the whites…

“I knew I looked white but I didn’t realize I was on the other side…. There was this merry-go-round, this swing, but none of us could get on it because we were Indians. And I said, ‘Bullshit, like this is here for all of us!’ and so we got on it. But the merry-go-round didn’t go too well with me cause I got sick. That’s a part of integration I can do without.”

Her upbringing was mainly Indian.

“My father was never, never, never around. The first thing I can remember is him coming home with a big bag of groceries, sizing up the situation and kicking the hell out of my mother….”

It’s a touchy subject. Her mother is a full-blood Tlingit, very beautiful by early accounts – now derelict.

“One day she disappeared. I guess that’s when my grandmother moved in. My mother would appear at various stages. I never understood why my father married her or what made her drink.”

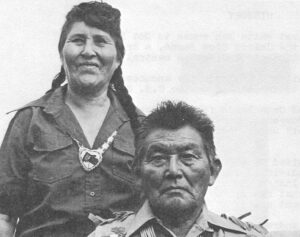

What little stability she found came from her grandmother. Her memories of the old lady are good ones.

“We were always on the beach, bright sun with all the rocks wet and the light in your eyes. And I saw this old lady coming toward us and she had this big pot full of salmon eggs. She started a fire and cooked the eggs for us. Then, what blew my mind, she poured milk on them.

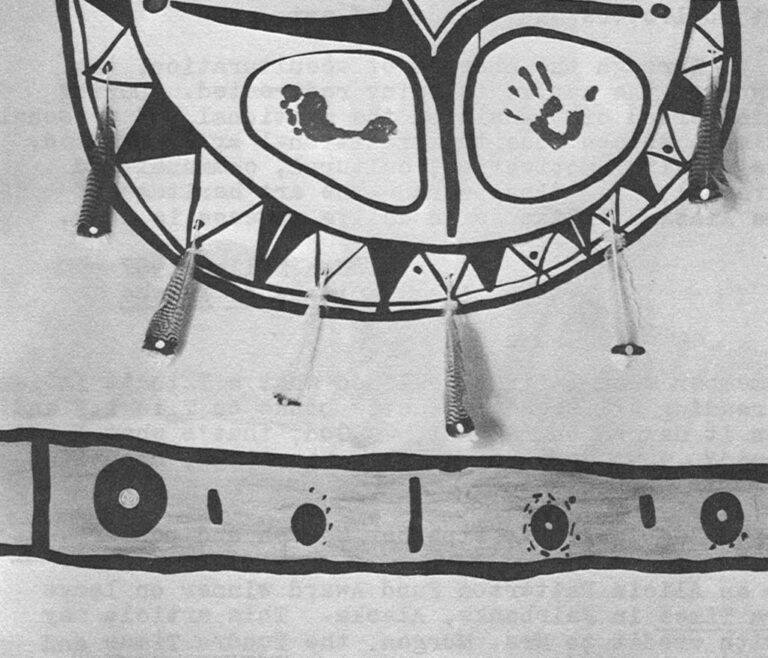

Tlingit War Shield 4′ x 5′ Oil

J.T. Shively Collection.

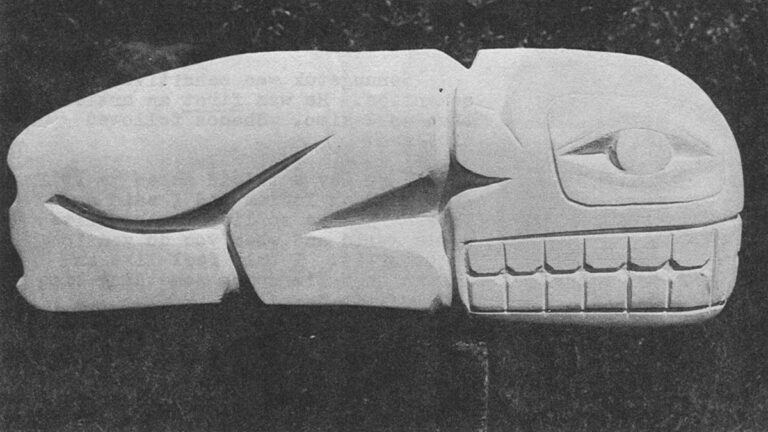

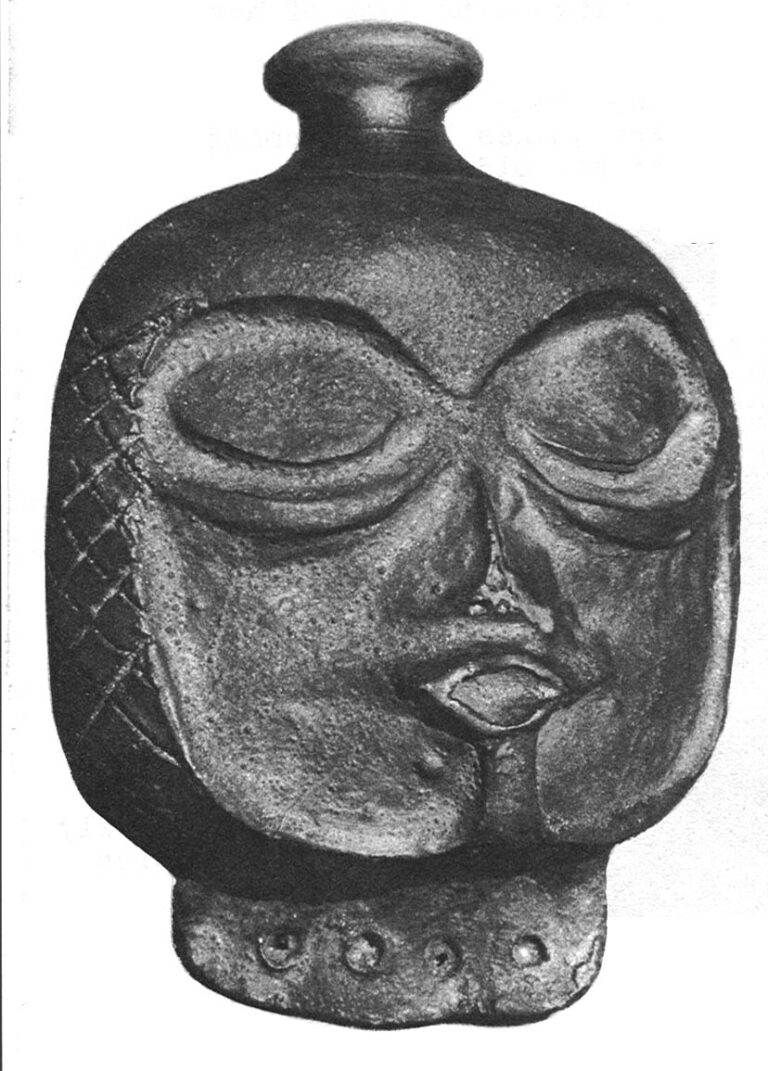

Totem 2 ½’ x 18″ Stone

J.T. Shively Collection

“She was my grandmother. She was about four feet five, really small. She had long white hair. Used to wear it in three braids; one on each side and one down the back.

“I don’t know about her husband. She wore a wedding band which was real thin. I guess he died soon after she was married. There seems to have been a series of accidents but I never figured out what they were.

“I was about seven when my grandmother moved in. At first we lived with her. Then she moved into my father’s house. She didn’t like living in a white man’s house. Thought it was too much of a hassle keeping it up. You couldn’t throw water out the door like she would at her place and you had to sweep and you were always doing things like making beds…wasting time.

“What really blew her mind was that she believed in the old ways and we went off with ‘Dick and Jane’ books and she didn’t understand what was going on.”

She spoke only a little English.

“Like if I brought someone home she would say, ‘Is this your friend?’ or ‘Would you like some dry fish and seal grease?’ And what I heard was, ‘Don’t drink. That’s no good!’

“Dry fish was her favorite food. She had no teeth so she used to pound it with a hammer on a log she kept by her bed. At night she’d get hungry and you’d hear her hammering that dry fish.”

The old Tlingit wore a traditional medicine bag around her neck and was reputed to be a shaman (witch doctor), but she left Shanon none of her magic.

“She always said some things were meant to die out. That when I was 20 I couldn’t live in the village because there wouldn’t be any fish left. That I’d have to live in the white man’s world.”

The grandmother took Shanon to visit neighboring Indian villages and, in turn, ventured into the white man’s world with her granddaughter. Shanon had a motorcycle with a little sidecar and her grandmother grew fond of riding in it. They favored the back roads where no one would stare at them.

“Thank God for the Salvation Army. My grandmother found a big, old shirt there and she used to tie it over her head so no one would see her. Those were the good days!”

The old lady died following a cataract operation she didn’t want, “in the hospital. Just where she didn’t want to be.” Her legacy to Shanon was her copper hunting knife and an Indian name.

“Skeek. It’s a bird that flies over the horizon. Someone who’s moving all the time. And it certainly came true.”

Trouble Is Assimilation

Shanon Gallant pronounces the world “trouble” very carefully.

“Trouble”.

It makes her slosh her Scotch around over the ice cubes and wander off into private thought.

Police record…?

“The only police record I have is ‘run-away’,” she says quickly. She knows I know the kinds of trouble she collected in the early years. I met her shortly after she got out of jail in 1965.

“Some of it I’m still paying for,” she reflects. “I don’t need it.”

She grew up tough – became a chronic run-away, out-of-sorts with a world she decided she couldn’t fit into.

“Assimilate. Either you do or you don’t survive. I even got kicked out of kindergarten. Supposed to play the cymbals but the damn things were too noisy and I didn’t want all that madness…. Told the teacher that my grandmother knew more than she did….”

Somewhere along the way – she can’t remember where in the jumble of private schools, juvenile detention centers and foster guardians – she got interested in art. And one afternoon, in her junior year at Juneau High, she walked into the office of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and told them if they didn’t find her an art school it was going to be downhill from then on.

She talked to Cleo Bennett, wife of Bob Bennett who was then director of the bureau in Alaska and later for the entire United States.

Mrs. Bennett, herself an Indian, had considerable interest in art.

“She told me if I was going to get accepted to art school I’d have to do some work, so I did. Then one day I’m up there at the glacier about 12 miles out of town shooting frogs and here comes Mrs. Bennett on her Honda and she tells me I’ve got 12 hours to pack and go to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe.”

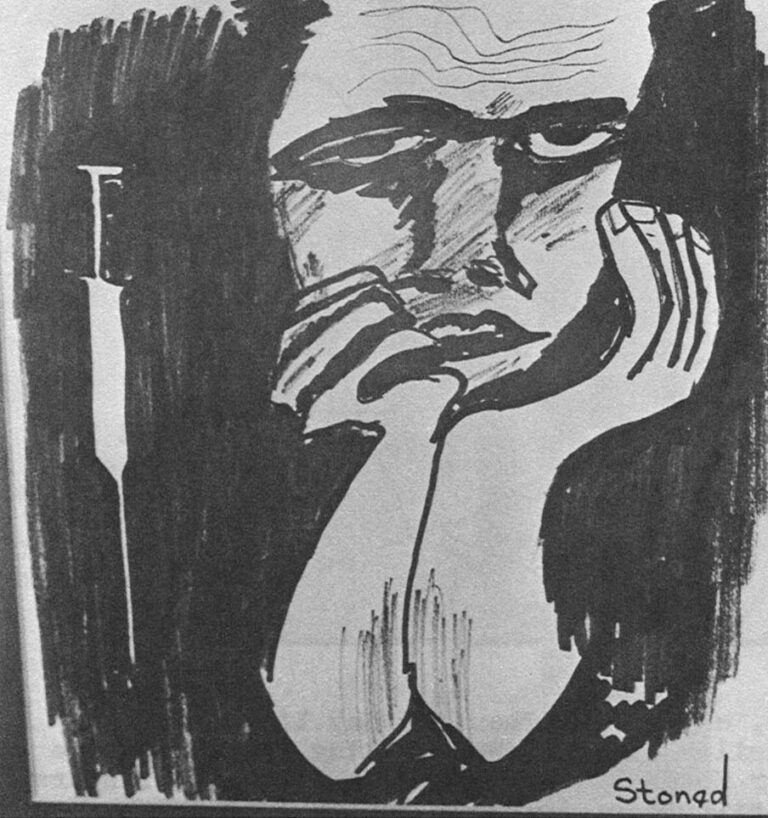

Stoned 7 ½” x 8″ Black and white ink drawing

Aron Wolf Collection

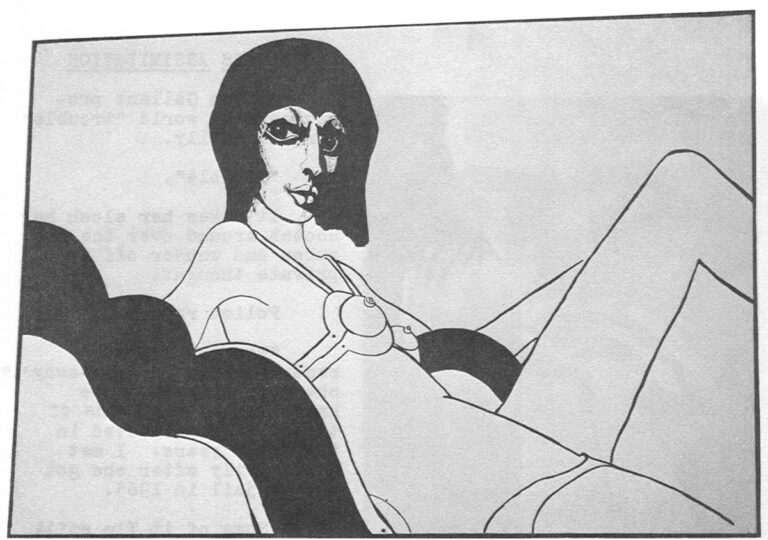

She III 3 ½’ x 5 ½

Acrylic on canvas Aron Wolf Collection

I’m Going To Dig Up A Few Presbyterian Graves

“I’m glad I went. At that point I was very interested in other Indians. There was a lot of hostility because we were competing.

“The Alaskans and the Indians from the east coast, like the Senecas, were academically the best artists. And just about anyone who is doing well now went to that school.

“The Institute of American Indian Arts is only 10 years old. A lot of it is ridiculous but people like James McGrath and Lloyd Neu have made a difference. They left a tremendously important impression on me although I didn’t realize it at the time.

“They showed me, ‘Wake up. You really have something. Don’t like keep it in the back room.'”

Her letters home during this period were uncertain and self-pitying. She was sure she would never survive to graduate but she did well scholastically and some of her art work was chosen for exhibit with a Department of Interior show that toured Europe in 1966 and 1967. Her first painting sold for $1,500 but she still didn’t think she had much going for her.

She didn’t want to go on to college, toyed with the drug scene, bummed around the southwestern states and came home because she hadn’t found any answers.

“I think I’ll go dig up some Presbyterian graves and find some artifacts,” she’d snort on off days. She read all the books she could find on Tlingits; mutilated the ones that reported her people dirty and uncivilized. Then finally she signed up at University of Alaska.

It was a rough trip. She refused to take money from the Bureau of Indian Affairs or her father, although she began to make her peace with him. She got a job driving a school bus in winter temperatures of 40° below zero, checked groceries and, once, worked as a flagman on a construction crew.

One summer she taught art to a group of underprivileged native “Upward Bound” students and was surprised to learn there were people in the world who had even less going for them than she did.

“Those people were already known as failures in their villages. Really down and out mentally. To show you how much, three of the 80 we had that year have since committed suicide.”

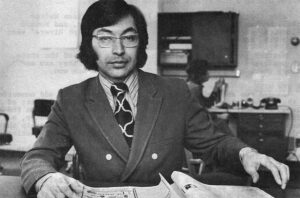

Half way through the university, she won a scholarship to study pottery in Japan. At first she was excited about it. Then she blew it, wandering off to explore the drug scene. In due time she came back, registered at the university again and began studying with Ronald Senungetuk, an extremely talented artist who is also an Eskimo.

Senungetuk was sensitive about semantics. He was first an artist, then an Eskimo. Shanon followed his lead.

“One day a friend asked me if I felt like an Indian and I said no because I have to live in the white man’s world and when you do you lose a lot of it. I only feel like an Indian when I’m doing something like this rattle.”

Thoughtfully she fingers a small, Tlingit dance rattle which is at once traditional and a departure from tradition. It was one of the first Indian pieces she did and she considered it a gamble at the time. Feared it might be confused with the tourist junk or – worse yet – that it would simply be a counterfeit of the old.

Dance Rattle 5″

Ceramic

Besides, her people never believed in art for art’s sake.

“Going to the museum when I was a kid, I was appalled to see what Tlingit things the white man trapped in glass boxes. I had a feeling these were every day things. Nice to have, but functional things.

“I never saw a Tlingit hang anything on the wall. Their art was so dramatic you didn’t need to hang it on the wall.”

Never General Electric

Today she’s still searching for her own ground but she has come to grips with her heritage.

“All my life I’ve tried to be white but all my basic patterns of eating and sleeping and thinking are just Tlingit and that’s all there is to it. I’m never going to be a General Electric executive and get up at 7 a.m. and that’s that!”

Recently she applied for admission to Loughborough College of Art and Design in England where she hopes to polish up the basics and learn more about the contemporary world of art. She’s experimenting with plastics and pop and current trends. Inventing some of her own.

But half of her work is now Indian – not tourist, nor counterfeit, but Tlingit 20th Century. Art judges keep slapping blue ribbons on these pieces and she hopes her old Tlingit grandmother would have approved.

Received in New York on July 20, 1972.

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.