Bethel, Alaska December 6, 1972

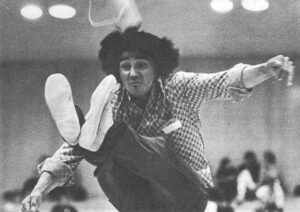

Wearily, Bethel Police Chief Tom Dillon went through his files:

“The man had frozen to death within 15 feet of the door to the house where the party was in progress. We figure he got sick, went outside and somebody locked the door. Never heard him trying to get back in.

“One woman died from exposure in an abandoned house. She’d gone there, intoxicated, for the purpose of prostitution. Must have passed out. The customer left and she froze.

“New Year’s Eve we had a snow machine take off. Found the driver later a quarter of a mile from a house. Held fallen off and frozen. The machine was still in working condition….”

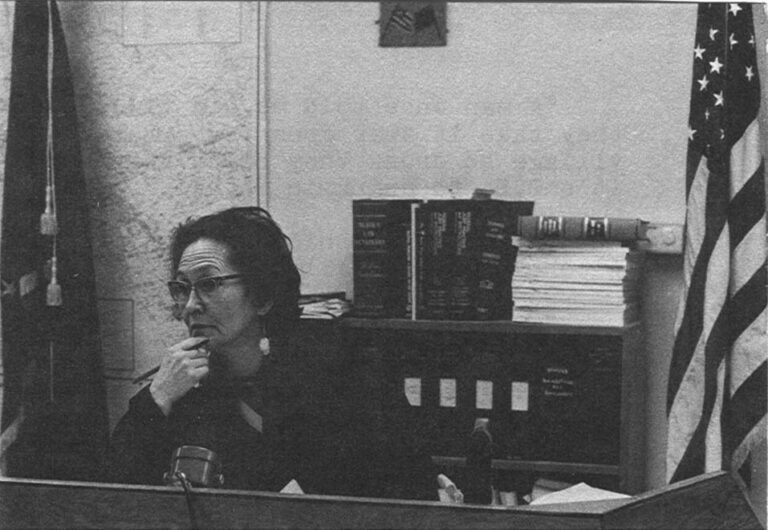

Tom Dillon, Bethel police chief.

Last year the Bethel Police Department had 14 similar reports to file under “Alcohol-related Deaths.” This year there have been four and, hopefully, next year there will be less. For Bethel, an Eskimo settlement of under 3,000, is making war on alcoholism. The odds against the town are as strong as 180 proof Everclear (a favorite drink of the Arctic) but some battles against the bottle are being won.

Bethel is a barge port on the Kuskokwim River in southwestern Alaska, 86 miles from the Bering Sea. It serves as a transportation center for Alaska’s western Eskimos but, because of its isolation and lack of natural resources, it has been slower to develop than other areas of the state and has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation.

Alcohol has long been a problem here, ever since the white traders arrived along with the Moravian missionaries in the latter part of the l9th Century. The first major attempt to deal with it was prohibition, back in the late 1950s, but it proved a dismal failure.

“I was mayor at the time,” recalls department store owner Dave Swanson, who represents Bethel on the State Alcohol Control Board. “Discovered if people were going to drink, they were going to drink, legal or not. I estimated in 1960 that $210,000 was being spent in bootlegging and the bootlegger called me up and said, ‘I think you’re a little low.’

“At that time the city had a total income of $54,000 and we spent $33,000 of it on police protection. We decided if we couldn’t stop the drinking we could at least put some of the profit from the sale of liquor back into the community and so we opened a liquor store.”

Originally the plan was hotly contested but today most of the opposition is silent. The business can gross as much as $6,000 in one day, opening at 12:30 p.m. and closing at 6:30 p.m. Its total gross last year was $779,214 which is $130,916 over the year before. The city came out with $268,897 gross profit, although the management plotted to discourage business.

“That’s why we don’t open until afternoon,” Swanson explains. “We figure if we don’t open until 12:30 maybe people will go to work sober. If we opened in the morning there’d be a bunch of them who would never make it.”

The idea of rehabilitating heavy drinkers came slowly to Bethel, perhaps because the majority of citizens refused to admit there was a problem. However by the late 1960s, with private bars in operation as well as the package store, drunks filled the jail and littered the waterfront.

A survey of 2,000 Alaskan natives, made by the Rural Alaska Community Action Program, showed 41 percent believed alcohol to be their number one problem. Judge Nora Guinn of the U.S. District Court headquartered in Bethel, estimated 95 percent of her cases were alcohol related. And the Bethel district reported among the highest (per capita) rates in the nation for homicide, suicide and wife beating…along with the lowest per capita income.

Making Do

In June of 1971 a group of concerned citizens mustered to open a small sleep-off facility where drunks could be taken, in lieu of jail, to sober up. They called it “Ekaiyurvik” which, in Eskimo, means “place of help” or “haven.” An inexperienced Eskimo staff was hired and trained for counseling with a main prerequisite that they be rehabilitated alcoholics.

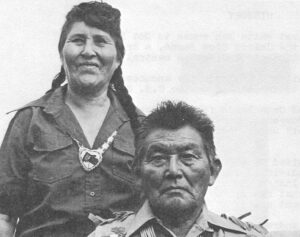

“It was our first attempt to face the drinking problem head on,” admits Eskimo Judge Guinn, mother of eight, who was a prime mover for the center. “We didn’t have funding so we started with what we had and made do with what we had.”

A trailer was found to house the program and citizens volunteered labor to build on a lean-to. Bethel Social Services, a combine of welfare agencies, donated $10,465; the regional Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation (YKHC), $10,000; and the City of Bethel, $2,000. This was eventually matched by $55,000 from the state.

“We had a statewide meeting on alcoholism with legislators, ministers, public service people and the like in Fairbanks,” recounts Rep. Joe McGill, area legislature. “Bethel sent two men. One never got past Anchorage and the other got to Fairbanks but was arrested twice in five days for being drunk in public and never did make it to the meeting. Naturally, we voted Bethel top priority in all state funding.”

Ekaiyurvik’s early case load was staggering and federal funds were secured to buy more equipment for the ill-furnished facility and to train additional staff. To date the center has handled over 6,000 cases.

Las Vegas of the Kuskokwim

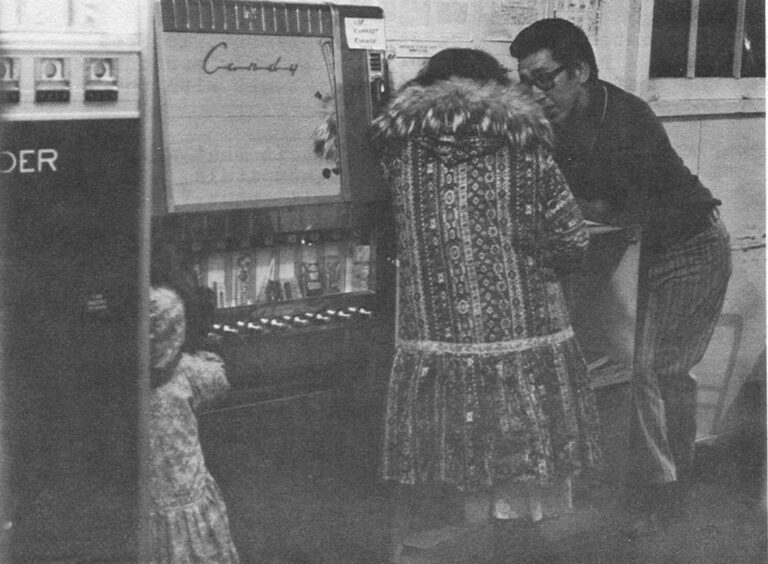

Such volume – twice the population of the town – is astonishing until you realize Bethel is a service center for some 57 Eskimo villages with a combined population of 15,000.

The town headquarters some 80 government agencies dedicated to fighting poverty, improving public health, etc.; along with two bars, a pool hall, two department stores, a new movie house and an astonishing fleet of taxi cabs.

“Bethel is the Las Vegas of the Kuskokwim,” maintains Dave Elias, a social worker for YKHC and chairman of the Bethel Council on Alcoholism. “It may not look like much to an outsider but coming in from the bush is different. Many of the villages are dry. And if you’ve got a little money, you can really swing in Bethel.

“A man once told me his village has no booze. If you bring it in, they take it away from you. But I’ve met people in Bethel from his village so drunk they can’t stand up. The implication may be that it’s O.K. to drink in Bethel.”

The motives behind the Eskimos enthusiastic consumption of Alcohol are debatable.

“Most of the people I talk to tell me they drink to get drunk. You don’t drink unless you’re going to get drunk,” observed Capt. Lorn Campbell, who with a two man force, represents the state police for Bethel and 57 small villages over a 93,000 square mile territory. “When they’re drinking, things that have been bothering them six or eight months…sometimes years, all come out. Seems like they keep things bottled up until they drink.”

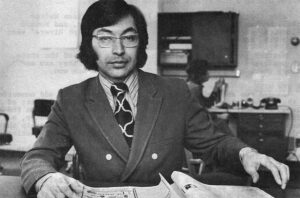

“Drinking is a custom. It’s kind of anti-social to turn down a drink. You get a couple of bottles and polish um off,” speculates Tom Anderson, Sleep-Off center director. “A lot of people drink because it’s a status symbol, I think. But there doesn’t seem to be any real pattern.

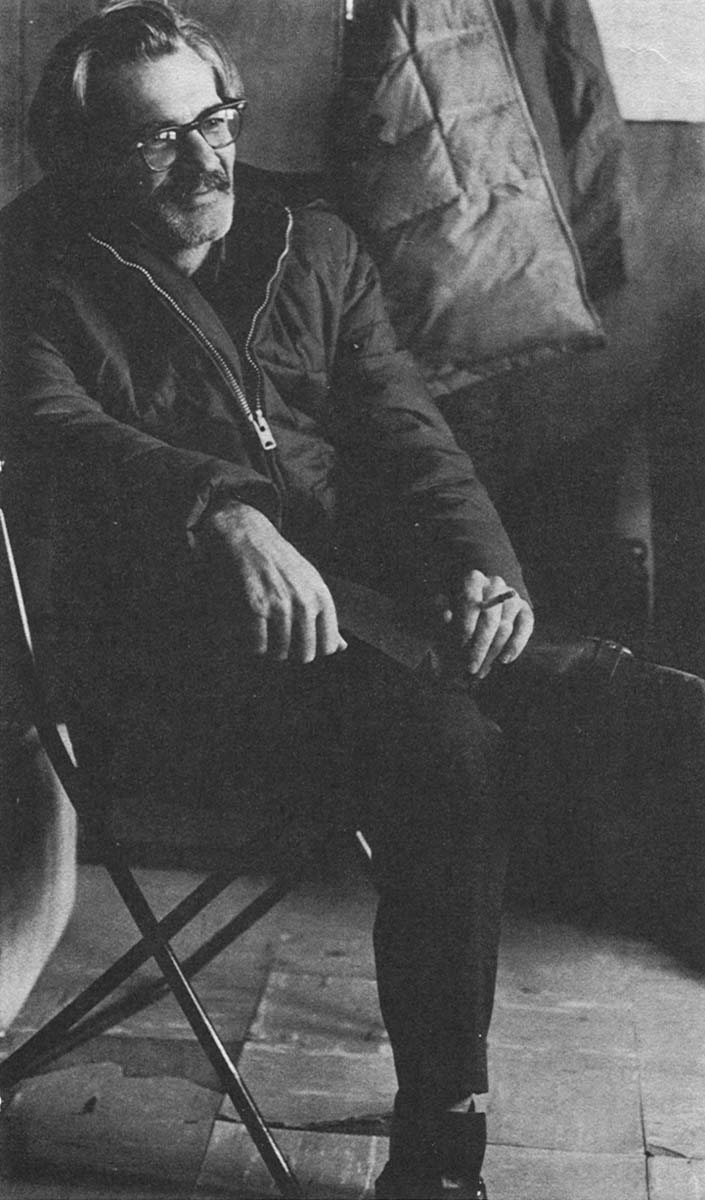

Tom Anderson, center director.

“I don’t think they drink any differently than anywhere else. It’s just that the Alaskan native is a little more honest about his drinking than a Caucasian. More apt to take a jug on the street.

“We have a great number of transients but they don’t act much different than small town delegates to an American Legion Convention in Atlantic City. There’s the same kind of alcoholics here as there are in France or Sweden or New York. I think, because life’s harsher here, alcohol is more likely to take a toll at an earlier age. You don’t find many 80-year-old winos in this country because they’re likely to have frozen to death at an early age.”

Anderson does believe some of his Eskimo clients have problems in making the transition from subsistence living in their rustic villages to the fast pace of the 20th Century.

“These people have a foot in each world, and they can’t decide which one to stay in. We try to help them decide which one they belong in and get both feet firmly planted.

“Sometimes we tell um, ‘Go back to your old ideas.’ There’s peace of mind in being able to walk on the tundra. To go fishing. To go hunting and berry picking. I think there’s nothing wrong with the way people have lived out here for centuries. Nothing to be ashamed of.”

Anderson is white, married to a Bethel Eskimo and the father of seven children. He received his training in community programs at the University of Washington in St. Louis and studied counseling at Lutheran General Hospital in Chicago. He is not bound to any cut and dried philosophy, however, in dealing with the problems of the bush.

“What we do is all the old things and a few of the new ones. First of all we don’t feed anything. We feel alcoholics have a certain amount of dependency and that will add to it. We give them coffee and a place to stay. Figure they found somewhere to eat before they got here.

“We try to get the individual to realize that he is responsible for what happens to him. We’re not. When people show they want to help themselves, we give them moral support.”

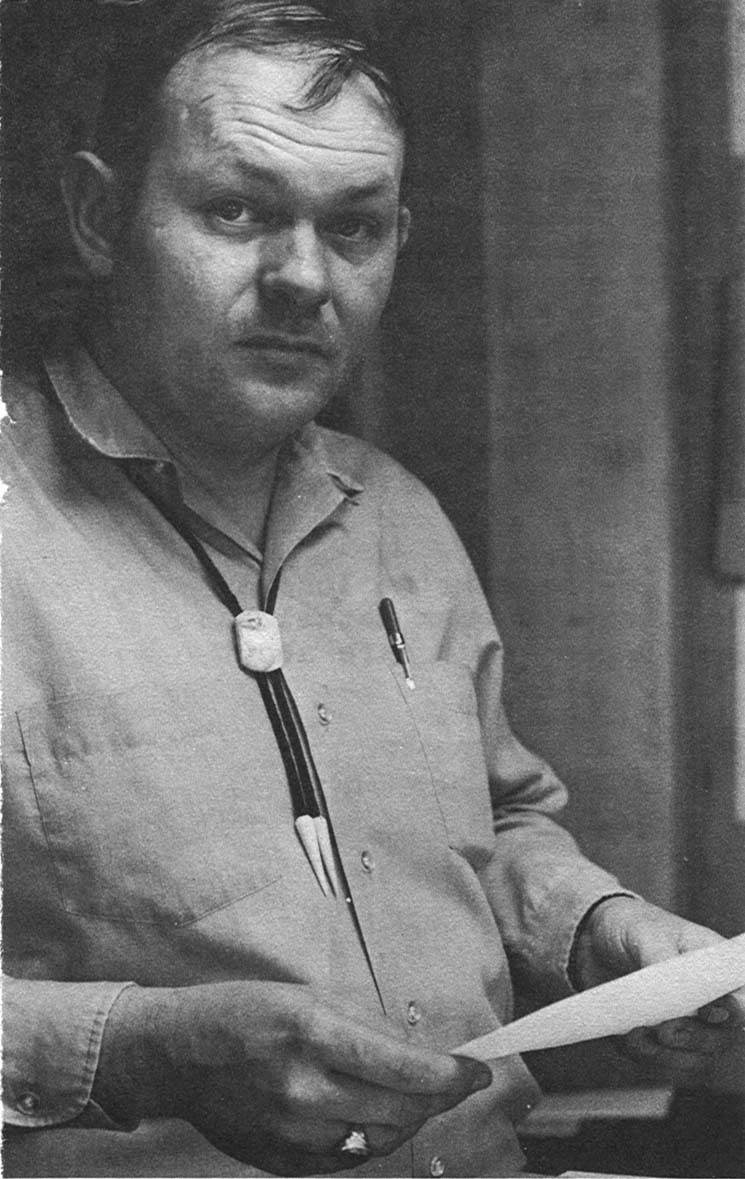

One of the center’s greatest assets, Anderson believes, is Fred Pete, counselor supervisor. Pete is an easy-going, highly personable Eskimo who, like all the staff, has had his private bouts with the bottle.

“I think I’ve went the route, if you want to put it that way,” he readily admits. “I’ve been through some of the hospitals. Been through some of the jails. I know what it’s all about.”

An ex-fisherman, Pete saw an ad for the counseling job posted in the Bethel Post Office and decided to try for it.

“He always tells people he hasn’t had much education, which is true,” Anderson said. “But he knows more about counseling than any man I know.”

The Ekaiyurvik staff and volunteers rely very personally on Pete for moral support.

“The social workers, Bureau of Indian Affairs counselors, they’re too pressed for time. Have regular hours, 9 to 5,” Anderson reasons.

“It’s not that so much but that they don’t share their experiences,” argues a pretty young Eskimo woman who recently sobered from a long binge to become a highly effective volunteer. “The social worker types wouldn’t admit to a personal problem if they had one. I trusted Freddy because I knew he’ had his own experiences. I really trust him.”

Although the center caters mainly to overnight binge drinkers, some patients, like the young woman volunteer, actually move in for a week or a month and work long hours just to be close to counseling. One particularly able volunteer was asked to consider taking a paid position as a counselor and was appalled at the thought.

“He’s not ready for that,” Pete decided. “He knows people here are finding ways to cope and he’s still trying to find ways to cope. A lot of people come here to get away from the pressure of the community to drink.”

However, a big percentage of Ekaiyurvik’s patients end up there because they have no other place to go and not for want of counseling.

“I always ask, ‘Why do you drink?’ and they usually say, ‘To have fun.’ Most of them don’t think they have a problem,” worries Simeon Arnakin, a veteran counselor. “They drink a bottle a day and they don’t think they have a problem. I explain to them about alcoholism. They’re surprised.”

A recent cut in federal funding (Title IV and Title VI funds) hurt the center because staffers hoped to invest in research to find more effective ways of combating alcoholism in rural areas. At one point they tried counseling door-to-door and found it surprisingly productive, but no one’s sure why. They also believe educational programs are a must, not only for villagers, but for themselves.

Most center staffers, including supervisor Pete, are currently taking psychology and sociology courses in Bethel Community College. They’ve watched outside “experts” try and fail in dealing with Eskimo problems. A better alternative, perhaps, will be Eskimos with a mixture of on-the-job experience and specially tailored schooling.

A New Law

Another problem faced by Bethel people is a new state law which prohibits police from arresting anyone simply for being drunk and will not allow involuntary commitment to the center without legal proceedings.

“We’re not really a warehouse for drunks any more or a dumping ground,” Director Anderson concluded. “Under the law they’re supposed to want to come here or be referred by a doctor. We don’t have the right to perform the service of protective custody.”

The late Tom Dillon, Bethel police chief, was bitter about the law and the hardship it worked on his department.

“It’s a confusing law and it should be reviewed,” he maintained. “Before, we had the option of taking a person to the Sleep-Off Center or to jail if he was going to be hostile. We had the option of protecting a violent person…a person who was violent to himself or to someone else.

“The new law treats alcoholism as a disease and we all agree with that concept. But it presupposes there will be adequate place for rehabilitation and a competent counseling staff. The type of treatment they’re doing now is nothing, more or less, than a sobering-up station.”

(Ironically, Dillon was shot to death two weeks ago and investigation is still pending. His alleged assailant is rumored to have been involved in a drinking bout and Dillon’s death may be listed as the fifth alcohol-related tragedy of the season.)

On The Right Track

Despite tight funding, an ever-increasing number of transients and problems with the law, most Bethel residents believe they’re on the right track with Ekaiyurvik. One proof is the counseling staff who have taken salary cuts to keep the center open. A year or two ago most of them were regarded as non-functioning citizens, and they’ve worked steadily and well of late months. Another proof is the increasing number of patients who check in voluntarily when their drinking problems become too much for them to handle alone.

“With the new law I really don’t see too much difference,” Judge Guinn considered. “The Sleep-Off Center is already established. They know it’s a place to come for help. And our officers have been scouring the books and are making some pretty creative arrests in cases of drunkenness where people won’t get help voluntarily….” she smiled. “I don’t expect any deaths in this office for not picking someone up on the road.

“What we’ve got to do now is go into rehabilitation. We know we’ve got to have more than the Sleep-Off Center and we’ll find a way to get it.

“You just use good old common sense. Something we’re long on here. We may fight among ourselves, sometimes, but when Bethel has a problem we always stick together. You know people do care about one another out here.”

Received in New York on December 11, 1972

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.