Anchorage, Alaska March 19, 1972

The Pipeline Will Do For The Caribou

What The Railroad Did For The Buffalo!

That’s the theme of a current conservationist poster and, if the proposed trans-Alaskan oil pipeline does block caribou migration, it bodes a cold and hungry future for several thousand Alaskan natives.

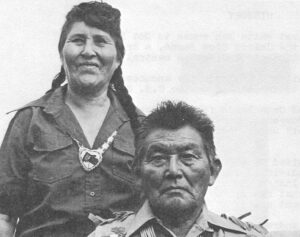

Over 20 Eskimo and Indian villages in the neighborhood of the pipeline depend on caribou for food and clothing. Some use the meat only to supplement their diets but tradition-bound villages like Anaktuvuk Pass, live almost exclusively on caribou.

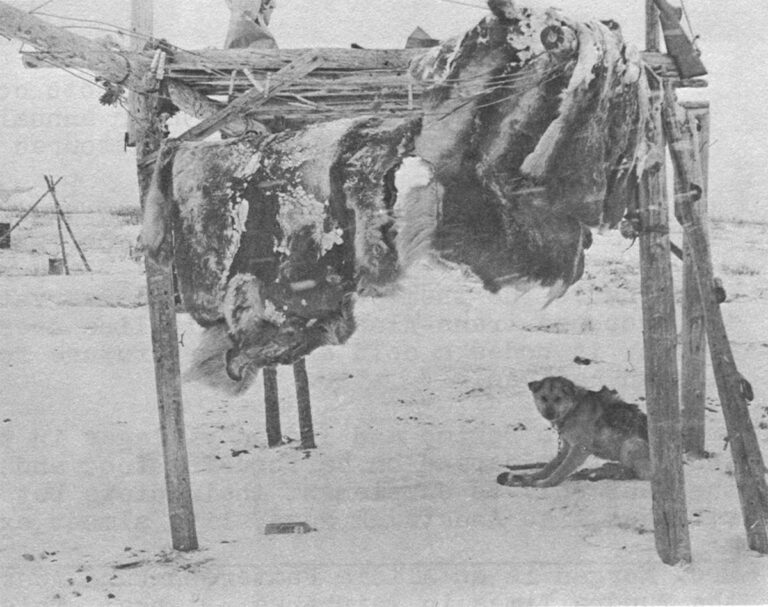

The average Anaktuvuk family consumes one caribou a week or one every five days if a dog team must be maintained. Almost all winter footwear is made of caribou skin and hunters need a heavy caribou fur atigi (parka) to survive. The Anaktuvuk people also use caribou skins for their small but growing mask-making industry.

There is little anti-pipeline talk among the natives, however. Many of them were employed on pipeline survey crews and look forward to jobs during construction. Pipeline development is regarded as a quick ticket to transition from a subsistence to a cash economy. And with a little luck, the caribou will survive to provide the best of both worlds.

Scientists know surprisingly little about caribou and have relied heavily on Eskimo reporting for the information they do have. Eskimos don’t boast much insight into caribou psychology either, although they have hunted the animal for hundreds of years.

Experienced hunters will tell you they watch for caribou, “anywhere, at any time in any numbers.”

Some biologists believe the animals acquired their wandering, habits as an evolutionary mechanism adopted to prevent overuse of range. Others see migration as a simple search for food and a calving area.

The natives sometimes advance the theory that, “Maybe, like people, the caribou have a lot of fun coming together in larger groups and traveling.”

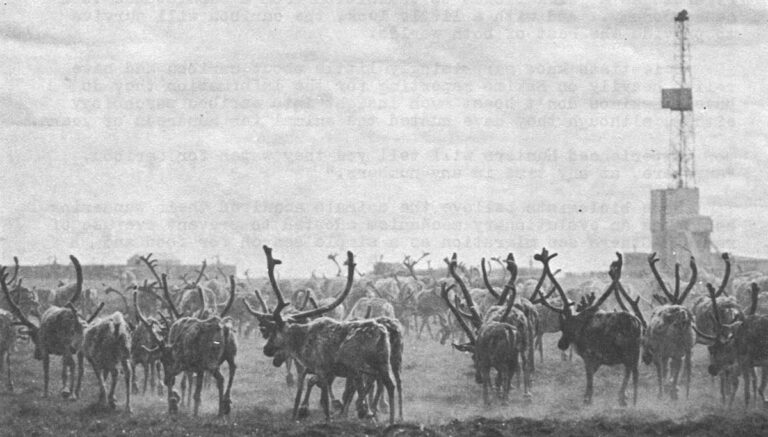

Whatever their motives, thousands of caribou gather in the spring to travel to open tundra where they drop their young. In the fall they return enmasse to the south.

This one at Anaktuvuk Pass is almost empty because hunting was poor last month. When caribou avoid the area, welfare handouts increase.

The hides hanging from the cache are caribou and much valued for clothing.

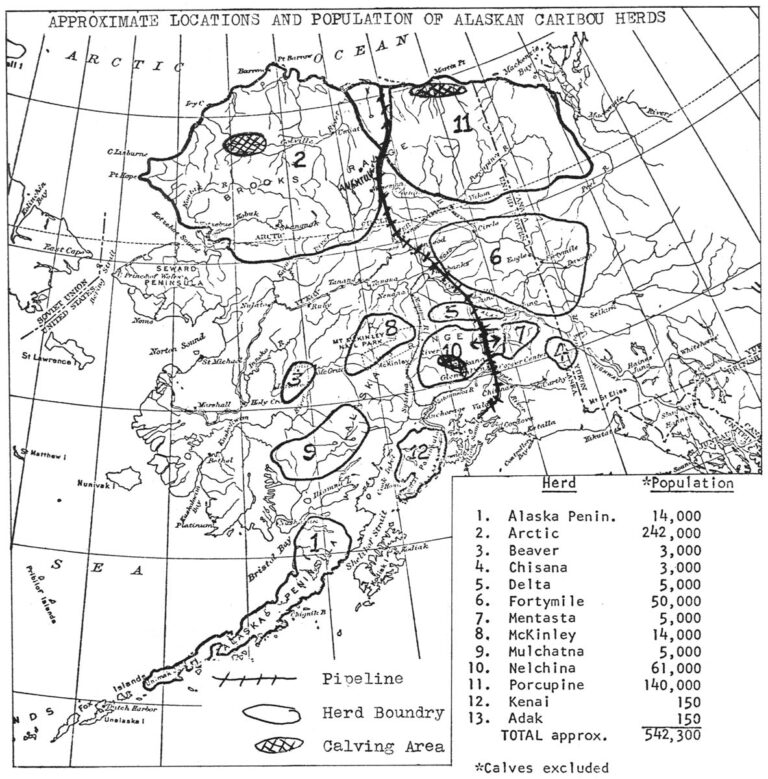

There are 13 caribou herds in Alaska and the pipeline would intercept three. One pipeline stretch lies on the North Slope from Prudhoe Bay south, where the gigantic Arctic and Porcupine herds mingle in search of good calving ground. A second, more crucial section would block the east-west migration of the Nelchina herd about 500 miles to the south.

Last summer, to study the reaction of caribou to pipelines, Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., B. P. Alaska Inc. and the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife established two simulated pipelines on the slope. Because this is to be a two year study, Alyeska has been reluctant to release findings to date but a report on the project made at a Canadian science conference last fall was not encouraging.

For one thing, herds didn’t show up for the experiment. Only 1,707 caribou appeared where thousands had crowded the slope the previous season.

Sceptics view this in itself as a bad sign, charging oil activity has already disrupted migration. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game does not find this alarming, however. The caribou have avoided that part of the slope before and, according to their studies, “areas known for many years to have great numbers may suddenly be abandoned as the herd changes its migration pattern.”

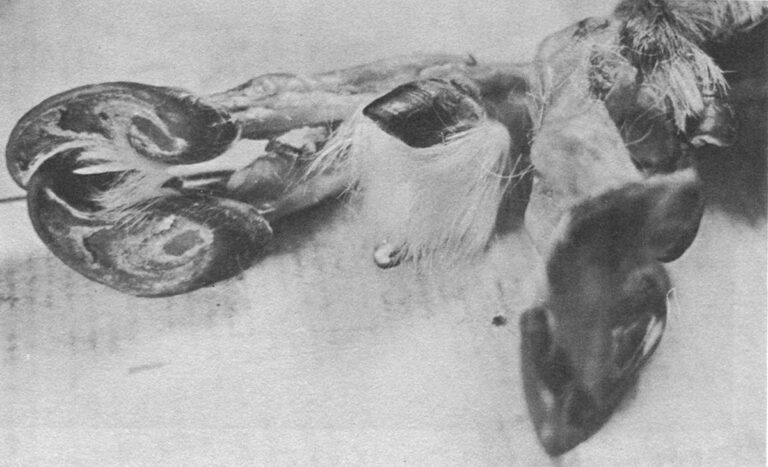

More significant is the fact that out of 1,707 encounters with the simulated pipeline, 83 percent of the caribou diverted from their original course. The majority turned back to the direction from whence they’d come and the rest detoured around the obstructions rather then use the series of ramps and underpasses designed for crossing. The B.P. Alaska mock-up was only 3,600 feet and Alyeska’s stretched a little short of two miles which is a short walk by caribou standards.

(Photos courtesy of Alyeska Pipeline) Simulated Pipeline – Most of the animals detoured, a few used ramps and underpasses and several crawled under the fence.

Peter Lent, associate professor of wildlife management at the University of Alaska and leader of the Alaska Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit conducting the study, does not seem discouraged by the statistics.

He’s planning to widen the ramps and underpasses and modify grades to make the pipeline crossing more inviting. His unit has also undertaken a similar study on the Seward Peninsula on reindeer which are domesticated caribou and easier to corral.

Lent refuses to make any predictions until his experiments are complete. The only thing he will say definitely is that “caribou are rather unpredictable.”

They have been reported climbing 5,000 foot mountains, negotiating 45 degree grades and swimming lakes and rivers. They can see a man a mile off and a day old fawn can outrun a human. They forage an average of 12 to 13 miles a day and can cover 25 miles a day if inclined.

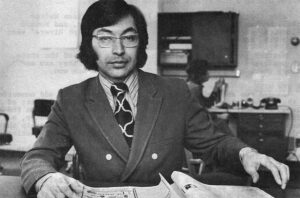

Cameron Edmondson, oil reporter for the Anchorage Daily News, believes the problem is overblown and wryly suggests a pipeline alternative.

“Why not get the caribou to pack out barrels of crude oil on their southward migration and have them return in the spring with supplies for the oil camps?

“Actually the gas pipeline through Canada (now in the talking stages) will probably be much more of a problem than the oil from the slope.”

Jim Hemming, formerly with state Fish and Game and now in the Pipeline Division, federal Bureau of Land Management, notes Alaska’s caribou herds have been increasing steadily while Canada’s declined.

At the turn of the century whaling crews hunted northern Alaskan caribou almost to extinction and mining activities reduced the Nelchina herd to under 10,000. Today the Nelchina herd numbers 61,000 and there are 382,000 caribou in the Arctic and Porcupine herds. In addition, herds have been transplanted to other areas bringing Alaska’s total to 542,300. Canadian caribou, which also faced extinction, now total 390,000 but the population remains static. Canadian biologists blame heavy hunting as the major reason that their herds don’t grow and claim Alaska has richer grazing area.

Approximate Locations and Population of Alaskan Caribou Herds

Hemming reports subsistence hunting of Alaska caribou dropped 60 percent with introduction of the snow machine, and a program to exterminate wolves (a major predator) also increased the caribou population. Only about 26,000 caribou are taken annually north of the Arctic Circle where there is no season or limit and about 1,600 animals are bagged elsewhere in the state where there is a limit of three per hunter.

The Alaska Fish and Game Department is expected to hold herds at present levels or even reduce them if range should diminish.

If the pipeline blocks herd migration and forces cows to calve in areas that won’t support them, Hemming warns the animals will be in jeopardy.

“If the pipeline is buried where there is conflict with the migration pattern, there won’t be any problem.

“But gradually we’re going to see reduced range,” he predicted. “If the North Slope is eventually developed at the level of the Prudhoe Bay operation, it will no doubt drastically effect the herds. Federal Petroleum Reserve No. 4 (staked around Pt. Barrow where the Arctic herd grazes) is an important calving area.”

Skip Braden, an Alyeska Pipeline spokesman, regrets that the public views the pipeline “like the Great Wall of China.”

As their building proposal now stands, much of the line in the crucial area will be buried, Braden said, and the Wildlife Unit will find alternatives.

“I’ve talked to a number of experts off the record and they candidly say they feel it’s a matter of acclimatization. That it might take two or three years but once the pipeline becomes a normal feature caribou will probably view it differently. Caribou are reasonably plastic in adaption to man.”

What hunters will do while the caribou are adapting is open to question. Statistics show that welfare handouts increase as much as 80 percent when herds bypass those villages dependent on them. Hopefully, pipeline construction jobs might fill the gap while the caribou are learning to use the ramps and overpasses and return to their regular routes.

In a promotional brochure Alyeska recently promised, “Environmental disturbances will be avoided wherever possible, held to a minimum where unavoidable and restored to the fullest practicable extent.”

Because of this plus the public scrutiny that their pipeline proposal has been given, many experts think that pipeline construction is less a threat than the activity that will follow.

Land man Hemming points out that recent federal land withdrawals for Wildlife refuge systems in Alaska will protect a good part of the caribou range but the rest of the grazing area will probably fall under the native land claims selection.

“It will be very important what the natives do with this land,” he maintains. “It may put the burden of caribou protection on the natives themselves.”

As for the analogy that the pipeline will do for the caribou what the railroad did for the buffalo, it’s debatable whether the railroad wiped out the buffalo or they were eventually doomed anyway. At any rate, conservationists should be heartened to know that Alaskan caribou herds are in better shape than the buffalo were when overtaken by the iron horse.

With caribou watching becoming a national concern, perhaps the independent animals won’t be “buffaloed” after all.

Received in New York on March 22, 1972

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.