Atka, Alaska October 14, 1972

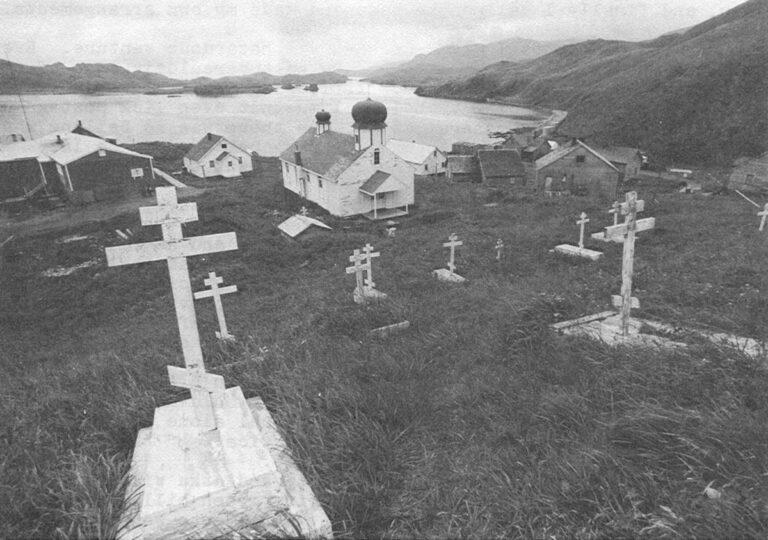

Atka, furthest west settlement in the Aleutian Islands, has no zip code, no post office, no functioning dock and no airstrip. Its only communication with the outside world is a fickle 50 watt radio and an ancient Navy tug, dispatched there once monthly, weather permitting – and the weather is the roughest in the world.

The island has 87 permanent residents of Russian-Aleut stock. They survive by working off-island part of the year and by subsistence hunting when they return with their modest savings. They love the huge, mountain-vested volcanic rock they call home and have fought hard to remain there. They are quiet, uncomplaining people, but they rank as the most neglected citizens in the United States.

The only way to get to Atka is through Adak Naval Base, 100 miles east, and military clearance is required. I was told to make arrangements through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) office in Anchorage but it proved tedious. They were vague about departure date; not even sure there would be a departure the month I wanted to go, and finally I called the base and made my own arrangements.

From all accounts, I was undertaking a hazardous venture. Every family on the island had an active case of tuberculosis, one of the military medical staff cautioned. If I drank the Atka water without boiling it, I was chancing typhoid. I mustn’t even lick postage stamps I bought at the general store, for there was no telling what I would catch. And most of the Aleuts were believed to be lazy drunks. Few outsiders could fathom why I’d want to visit.

Departure of the Navy tug was postponed two days, although the weather was fair. The Navy blamed the BIA and the BIA blamed the Navy. Finally someone got it all together and we found ourselves chugging off on the World War II harbor tug. It had enclosed passenger seating for six and there were about 20 of us aboard, not counting the crew. No food, either. The Navy provided it when they made the run with a bigger boat, but that craft had been moved to another station and there was no room for food service on the 100 foot harbor tug. We passengers hadn’t been warned, but you couldn’t blame the Navy. They’d contracted with BIA to provide Atka transportation only because nobody else would undertake the assignment. It cost the military $375 in fuel alone to make the run and BIA paid them only $200 for the service.

It was a cramped hungry, 12-hour trip, and Atka village, tucked serenely into an amphitheater of sheltering green hills, was a welcome sight. Our reception was warm. The Aleuts wouldn’t take money for ferrying me ashore or carting my baggage. In the absence of the village priest, I was established in his comfortable house for $120 rent which went to the church, and, although I was a stranger, villagers were very much concerned about my welfare.

Atkans had their hands full too, that first night. Originally the tug had been expected to stay two days. Now it was announced departure time would be at six the next morning. Visiting bureaucrats would have to cram two days discussion into the evening hours. The Navy doctor and dentist were likewise pressed. Families with children to send outside to school had to rush with packing and there was a month’s mail to be read and answered before dawn.

Adding to the rush, the visiting representative of the Aleut League, a regional native organization to which Atka belongs, called a meeting of all villagers. An education specialist from State Operated Schools showed a movie on an Eskimo bilingual program and asked if Atkans wanted to teach Aleut in their school. If so, could they decide by 6 a.m. who they wanted to teach it, whether or not he would travel to Norway to study with a leading Aleut expert and whether he would teach the language in the traditional Russian (Cyrillic) alphabet or in English?

Then the Aleut League representative explained that anyone from Atka could run for the League’s board of directors. She wanted the name of a candidate. She also wanted to know if anyone wanted to take training to teach an adult education course and if someone would serve on the Aleut League planning committee on early childhood education.

All the assignments involved traveling a thousand miles to Anchorage where the Aleut League is headquartered, then hanging around the city a month or so, waiting for the next tug home. Both speakers finally conceded it was impossible for the villagers to make so many important decisions overnight. Perhaps the people would send their answers and representatives out on the next tug.

Proceedings were interrupted when the new school teacher’s wife burst in to announce that their packing boxes had been left on the beach and were getting drenched in the rain and incoming tide. The meeting broke up to move the teacher’s belongings. The dentist worked on, using a weak light and his hand as a head rest and lost a tooth root in extraction from a young patient. The medical man offered shots for TB tests and villagers (who tried unsuccessfully to explain they’d had similar tests a month earlier) gave up and went through it again, later proving negative.

Morning came all too soon and a group of weary parents and friends trooped down to the harbor’s edge to say good-by to the high school youngsters. State Operated Schools had never been able to afford a high school on Atka so the children were used to traveling to Adak or a federal Indian school in Oregon. There were no big displays of emotion. A kiss and a quick embrace and the students were off on the tug. With them went our last sure contact with the outside world.

Simple and Easy Going

Happily I settled into village life, which was simple and easy-going. I was adopted by Danny Boy Snigaroff, a 10-year-old whose mother was in Anchorage training as a health aid. With his friend, Michael Dirks, 11, he guided me over foot paths and hunting trails, climbing mountains of ever increasing heights and fishing swift swimming salmon with a hunting knife tied to a stick.

Snigaroff’s white-footed Labrador, Hippy, moved in as my watch dog and their cat, Zizzi, roosted on my windowsill. Ruth Kudren, 13, and her sister, Molly, 14, also kept me company. When I asked to meet their mother, Ruth said evenly that I would have to go to the cemetery. She’d been dead three years.

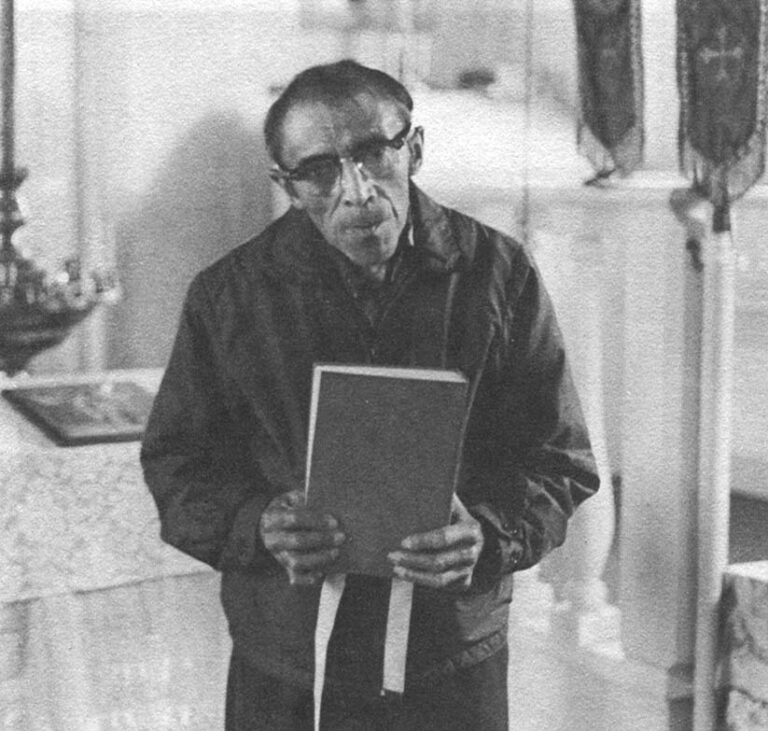

There were a few parties but no real drunks in the village. The people were friendly but terribly sensitive, fearing I might find them uncivilized. Actually, the reverse was true. Atkans are meticulous about neatness and appearance. For church, which is a must, the women wear dresses and nylons and I had brought neither. Since I was the tallest woman in the village, it was impossible to borrow and finally I asked Poda Snigaroff, church reader, if I could attend in my slacks. He decided it would be all right, “provided you are clean” but some of his congregation never did adjust to seeing a woman garbed in britches at their solemn Russian Orthodox services.

Physically, I never felt better. I drank the water without boiling it and found it a welcome change from the city variety. Village hunters and fishermen kept me supplied with meat without my asking and I purchased 50 pounds of flour and entered an informal bake-off contest against industrious Atka housewives.

Because these people value their language more than most, and because it is a beautiful tongue, I asked for an Aleut teacher and Moses Dirks, 19, one of the village’s most able hunters, volunteered. He had gone from Atka’s underpowered grade school to high school in Adak with a sixth grade English reading level and worked hard enough to graduate with honors. Now he was home, living by subsistence and enjoying the peace of the island, but he was still interested in education.

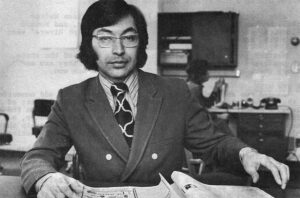

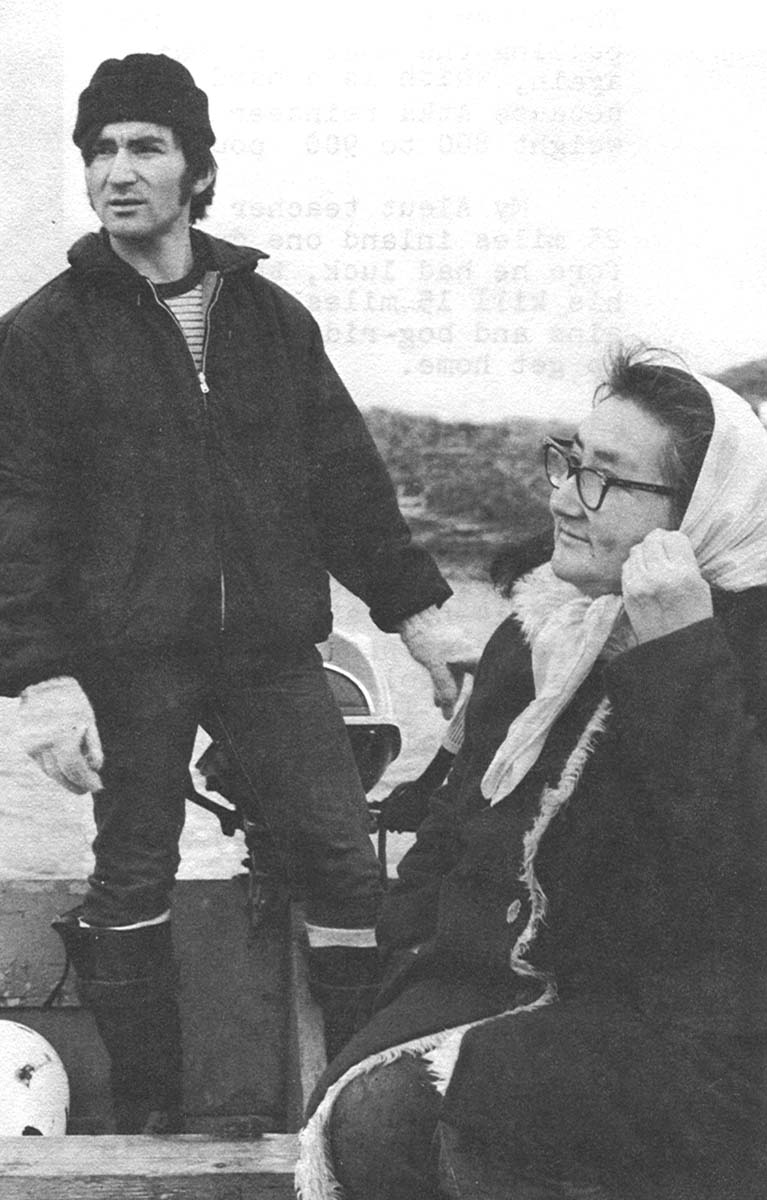

Moses Dirks and his mother, Lydia, head for the family camp.

At first he feared he’d be a teaching failure, but he stuck to his task between reindeer hunts and in a month I could say what I wished in Aleut…Everything except the word “no”, that is, which he insisted was not included in his dialect.

Actually there is a shortage of negative thinking in Aleut. There’s no word for “suffering”, for example, and no word for “good-by.” And it’s almost impossible to shout in the language. Aleut is a gentle tongue.

But life is sometimes as hard as the language is soft. Because there is no electricity and no refrigeration, the people are required to forage constantly for food. Even a man with savings must hunt for fresh meat for his family and there’s no easy hunting. The island has a circumference of over 200 miles and its ample reindeer herd has long since gone wild to range far from the village.

Sometimes hunting parties walk about three miles inland to a lake where they keep a boat and engine. Crossing the lake, they haul the craft down a shallow stream to the sea on the back (north) side of the island and often coast three or four hours to locate the herd.

Then they pack home the meat, pulling the boat upstream again, which is a hard job because Atka reindeer often weight 800 to 900 pounds.

My Aleut teacher hiked 25 miles inland one day before he had luck, then packed his kill 15 miles over mountains and bog-riddled tundra to get home.

Those who are skilled seamen sometimes brave Amalie Pass (a rocky channel with a 12 knot current marked unnavigable on most charts) to follow the lower coast in their 14 foot skiffs. Such trips are expensive, though, because gasoline costs $1.05 a gallon. The day I made the run, we really went in the hole, cruising six hours only to come home empty handed because the deer moved inland.

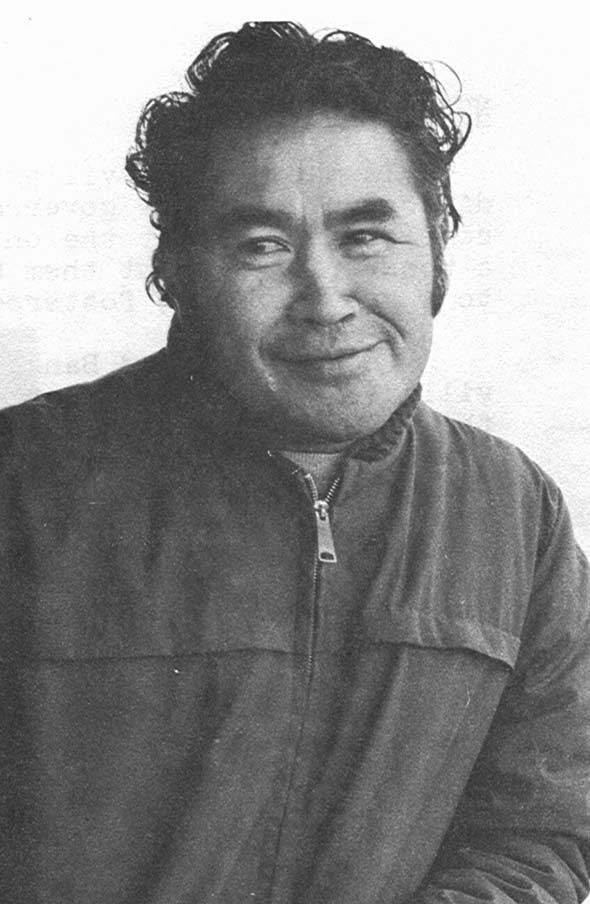

Islanders are also avid fishermen, going out in the rottenest weather to check their nets and halibut lines. The most ambitious of them cannot live by subsistence hunting alone, though. Mike Snigaroff, village president, estimates he needs $3,000 in addition, to support his wife and five children. To earn it he hires out as a commercial fisherman, often traveling hundreds of miles to find work when no cannery boats are in his area.

Many Atka women weave grass baskets of such excellent quality that they sell from $100 to $500. The grass can only be gathered in certain summer months and takes many weeks to cure. Often, because there is no post office and no way to insure a package, their work is lost enroute to potential buyers, and the women never realize financial gain.

Although many Atka families qualify for welfare, only two are currently enrolled. One is a woman with four fatherless children and another is an older man whose health has failed. Usually the village takes care of its own, explains Innokenty (Popeye) Golodoff, Atka treasurer.

“If a man goes off the island to work, he puts $2 in the village fund and any person who can’t work can borrow from it. Right now we’ve got $200 left but if all the loans came in, it would be up to $500.”

No Grumbling

In many native villages there is considerable grumbling and discontent with the government and the system, but Atkans do little complaining. About the only thing that riles them is mention of a book written about them by a budding young anthropologist which, to a great extent, fostered their reputation as indulgent drunks.

The writer, Ted Banks II (Birthplace of the Winds) visited the village in a troubled period of adjustment after World War II. On the Japanese invasion of the Aleutians, the U.S. Navy burned Atka (so as not to give the Japanese quarter) and evacuated residents to Southeastern Alaska. The change of climate (which was less stormy but much colder than the Aleutians) and diet resulted in the deaths of about half the refugees and the survivors were struggling to get reestablished when Banks descended. Also in residence at the time were 300 GIs who were helping rebuild the village, and life was anything but normal for the Aleuts.

Banks tried to take these changes into account but he left leading questions unanswered. Why had the Aleuts abandoned their old ways, he asked? Why had they given up the marvelous skin boats of their forefathers in favor of wooden skiffs? Why did they eat canned fruit instead of picking berries? Why didn’t they hunt more reindeer?

There were plausible answers – a shortage of game, the tartness of the local berries which require so much investment in sugar that it’s cheaper to buy jam – but Banks didn’t pursue it.

In addition he wrote, “It is a picture that is all too familiar to anthropologists. A once-hardy, populous group, admirably adapted physically and culturally to the rigorous environment – now impoverished, diseased and spiritually weakened, their numbers alarmingly reduced and their former culture all but destroyed…The Aleut seems likely to follow the Dorset Eskimos to extinction before our very eyes.”

“He told us that, too,” recalls Nadesta Golley, village secretary and mother of a lively Atka high school student. “But we’re still going.”

Twice in the last 60 years the population of Atka has been halved. In the early 1900s influenza took its toll and then displacement during World War II. This is the pattern of history with the Aleuts, though, and they’ve come to accept it.

When the Russians discovered the Aleutians in the mid-1700s every island in the chain was settled by this fierce, proud race. Their spears proved no match for the guns of the Russian fur traders, however, and by the time the land was sold to the United States in 1867, the population had dwindled from an estimated 20,000 to 1,000.

The sea animals, on which the Aleuts depended for food, clothing and skin boats, were depopulated on about the same scale and sickness and starvation became a way of life.

In addition, the Russians had obliterated the Aleut culture; tribal traditions and even tribal memories. To replace them, they left the comforts of the Russian Orthodox Church and a written Aleut language, but American administrators banned both from the education system.

Yet, despite centuries of pressure to conform alien cultures, the people have retained their identity as Aleuts and are proud of what they’ve salvaged. Their children are remarkably bilingual, bound closely to their church and village. Many are good hunters and basket makers, and a fair number of them who are deported to schools and job training outside the state, still come home or desire to.

The Future is In The Balance

Today, the future of Atka hangs in the balance.

“When I came back to Atka after World War II, my buddy said, ‘Why are you going to the Aleutians? They say even the seagulls are leaving there.'” recalls Dan Prokopeuff, village vice president. “I told him I was going because it’s peaceful and quiet here. But if we can’t get things straightened out pretty soon, I’m going to have to move.”

Prokopeuff has had the care of three teenaged daughters since their mother died three years ago and he must work off-island at least a third of the year to support them, leaving them with his mother who is 84.

Mike Snigaroff, village president, is also considering moving his family to Kodiak where he often fishes commercially. Last month, in his absence, his young son, Simeon, nearly died for want of medical care and his wife did not have money enough to heat their home at night.

“I may have to move but I want to do all I can for the village first, to see if I can make it go,” he said.

“The problem is that we’re living like 40 years ago,” ponders Larry Dirks Jr., 23, who came back to the island with his wife and young son after two years at Anchorage Community College.

There are no jobs on the island. There is no electricity to make a young wife’s life easier; no communication with your family when you go off-island to work.

With the Help of the Men of Atka

According to one estimate, islanders can have all the electricity they need if they tap one of the spectacular waterfalls near the village for hydro-electric power. The Navy is willing to help with the planning. All they need is $13,000 worth of material and the labor of the men of Atka.

The village can acquire surplus steel matting from Vietnam to build an airstrip. All they need is the men or Atka to lay it.

There is material on hand to build a new cooperative village store. All that’s needed is the help of the men of Atka to build it. And the same for a new village water system to replace the hook-up installed by the Navy in the 1940s. Again the men of Atka will be called on for repairs. But how, they wonder, can they find time to do it all between commercial fishing season and the time they spend subsistence hunting to support their families?

Then there is the problem of village housing. Most of the homes are comfortable and fairly modern, but they were built in a crash program 30 years ago and are fast deteriorating. The island is often hit by winds of 100 knots or more and at least two homes are already tearing at their foundations.

Atka applied for a federal housing program but, because there were no Atka people to lobby their regional organization, other villages gained priority although their needs were not so great.

Atka residents have never seen their legislative representatives and they’ve never been visited by the president of their Aleut League, although he promises to make the trip.

“It’s sort of like…. Well, we’ve been forgotten,” observes Larry Dirks Sr., a lifelong island resident.

And Dirks has substantial reason to believe it. Last year, like some of his neighbors, he filed for a native land allotment under a government ruling passed in 1906, making it possible for natives to legally own land they use and occupy. He could have claimed 160 acres with additional tracts of the same size for his wife and four of his seven children. Instead, he filed for only 40 acres around the summer campsite that has been used by his family for generations.

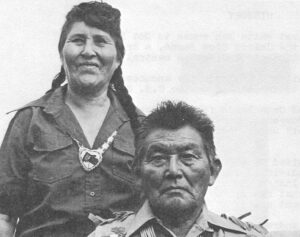

Atka

Past and future.

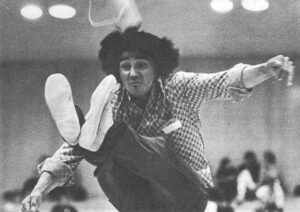

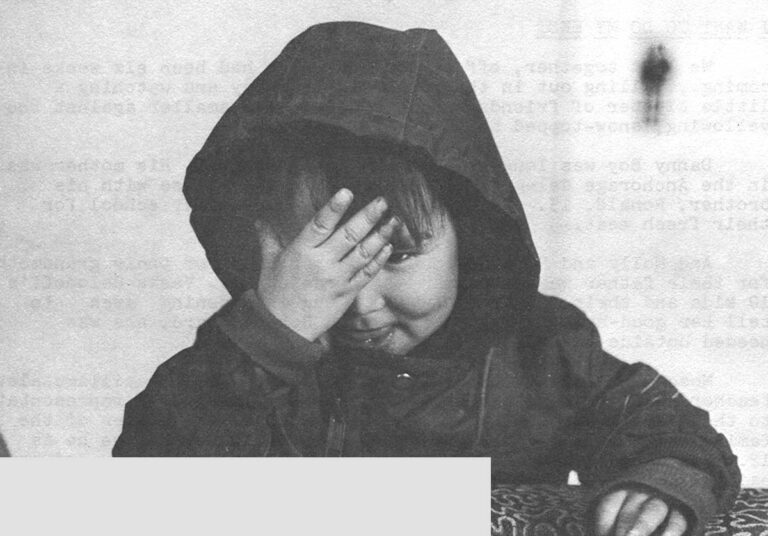

Above Kevin Dirks flirts with the camera.

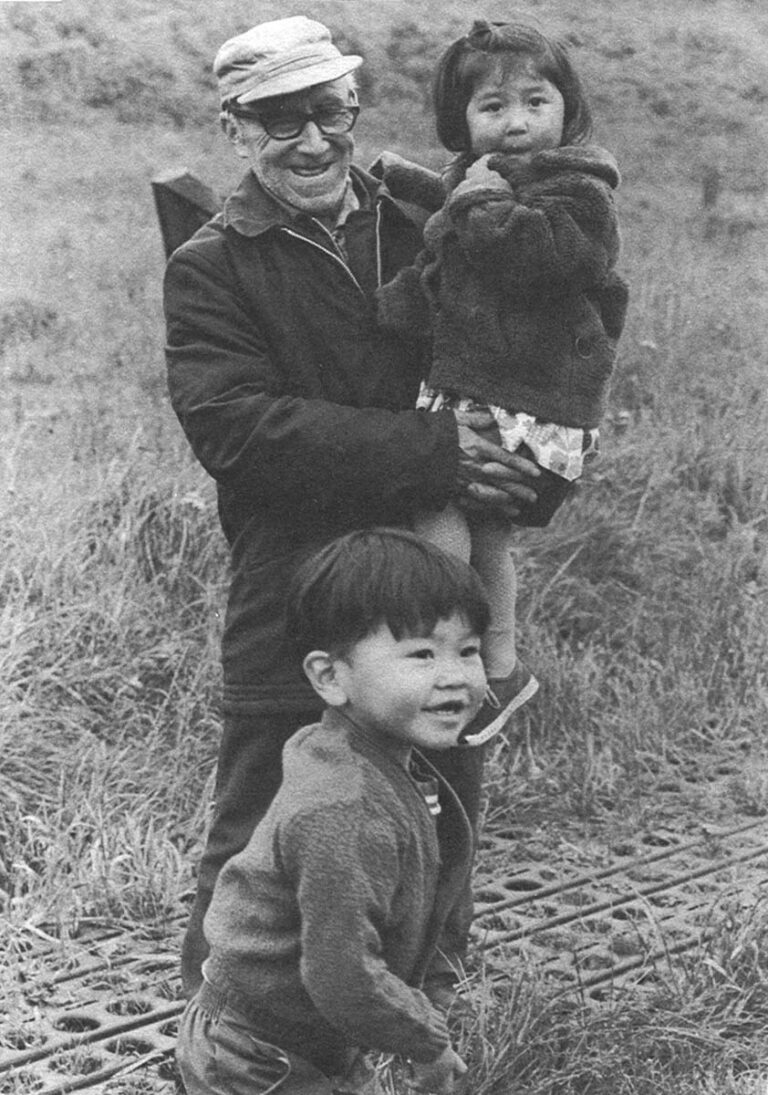

Below Phillip Nevzoroff with grandchildren Mary and Simeon.

“I could have claimed more but there was a time limit,” he explains. “And I don’t need that whole mountain up there, anyway. We do want the campsite. It’s been in the family as long as anyone can remember.”

But a letter from the federal land office informed him this August that he could not have the land.

“On March 3, 1913, Executive Order 1733 reserved the whole Aleutian Chain…and set it apart as a preserve and breeding ground for native birds, for the propagation of reindeer and fur bearing animals and for the encouragement and development of fisheries,” wrote the land office manager. “Accordingly, the application is hereby rejected.”

The letter also informed Dirks that he had 30 days to appeal the ruling but on Atka that’s no easy assignment. Villagers are not allowed to send telegrams via the radio they use to communicate with the school on Adak and mail service is nebulous.

Luckily Dirks read his letter the night it arrived and asked visiting member of the Aleut League to undertake his appeal. Eventually, it’s hoped, the Aleutians will be reclassified to allow the natives full and equal citizenship with the birds, fish and fur bearing animals.

“We’ll go to the Supreme Court if we have to,” warns Mike Swetzof, Aleut League head. “The whole damn Aleut community was never recognized in the past. Never had any representation except personal interests. We’re finally breaking out of that.”

Looking Out For Their Own Interests

The people of Atka certainly hope so, for if their regional organization goes to bat for them – not only for land but on other issues – it could mean the survival of their village.

Atka shares its transportation problems with other Aleutian settlements and it’s hoped the Aleut League can come up with a solution more viable than leasing the Navy tug. If Atka has reliable transportation, villagers have been told, they can have a post office. And if the island has transportation and mail service, cannery ships will be encouraged to station there, offering jobs right at home.

Through a corporation of the Aleut League, Atka will also receive it’s share of money and land from the federal land claims settlement, which should give it a fair capital base from which to operate.

“Communications will be our first priority,” speculates Mike Snigaroff. “If we can solve that problem, we’ll be on our way.”

The people of Atka have never been to a meeting of the Aleut League but this month, to defend their interests, they’ve mustered a delegation of seven to attend the League’s annual convention. It is a severe hardship for such a large percent of the village population to leave the island. Their dependents will have to fend for themselves for at least a month and maybe longer if the tug is delayed. But it’s a necessary trip if Atka is to remain a viable village.

I Want To Do My Best

We left together, off on the tug which had been six weeks in coming…pulling out in the first light of day and watching a little cluster of friends and loved ones grow smaller against the yellowing, snow-topped hills.

Danny Boy was long-faced, trying not to cry. His mother was in the Anchorage delegation and he was to keep house with his brother, Ronald, 15. They would have to hunt after school for their fresh meat.

And Molly and Ruth would be alone to care for their grandmother, for their father was with us. And three of Mrs. Vassa Golodoff’s 10 kids and their father circled our tug in widening arcs to tell her good-by. As head of the Atka School Board, she was needed outside the village, too.

Moses Dirks was with us to go in training as the village Aleut teacher and with him, his brother, Larry Jr., who is a representative to the Aleut League. That would leave Michael the hunter of the family and he will probably bag his first reindeer before he is 12. But so much responsibility to leave the youngsters…and how painful to leave!

Mike Snigaroff stood by the rail until the village disappeared behind the big volcano on the western end of the island and the whole rock became a distant haze of gray.

“I want to do my best by it,” he said quietly. “But I just don’t know how it will come out.”

Received in New York City October 26, 1972

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.