Fairbanks, Alaska December 30, 1972

Six years ago the Alaskan native was a political nonentity. Statewide candidates, the state legislature, polsters – just about everybody but the welfare agencies – ignored him. Under the U.S. Constitution he had a vote, of course, but he wasn’t expected to use it.

Today, although Indians and Eskimos represent only a fifth of Alaska’s population, their vote constitutes 25 percent of the total ballot, which no statewide politician can afford to ignore. Nine Eskimo and Indian delegates currently serve in the state legislature, which is more than the total number of Indian representatives in the rest of the United States. And voter education is high priority in future planning of native leaders.

The potential of the native electorate was first recognized in 1965 when Democrat Mike Gravel, then speaker of the State House, figured if he could garner the “Bush” vote, he could win a statewide election, even if he lost in all three major cities. With this in mind, he backed the building of regional high schools in rural areas and cultivated native alliances.

Gravel was defeated in the race for the U.S. House in 1966, but only because his losses in major population centers were heavier than he’d anticipated. His faith in the native vote was sound and carried him to a U.S.Senate seat two years later.

Also courting the natives in 1966 was Republican Walter Hickel, making his debut as candidate for governor, and Howard Pollock, a veteran state legislator out to win Ralph Rivers’ seat in the U.S. House.

Neither man had traveled much in remote areas of the state. Both professed shock at the conditions of poverty they saw among natives there and pledged to seek remedy. Both men won.

The New Wave

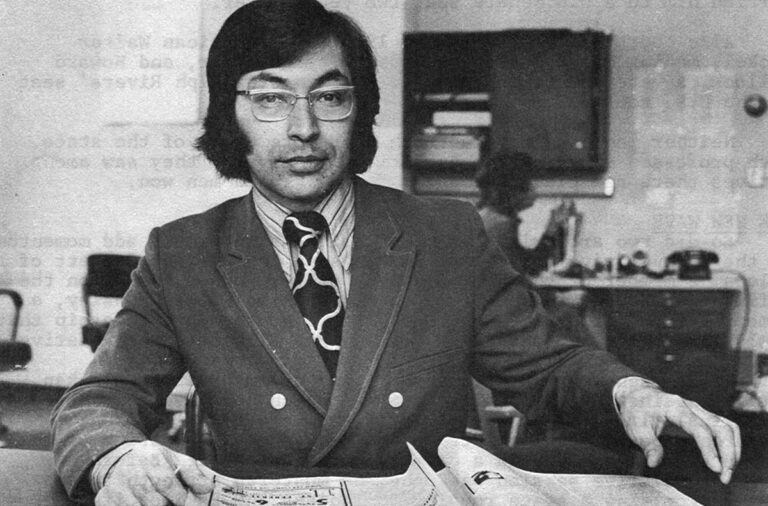

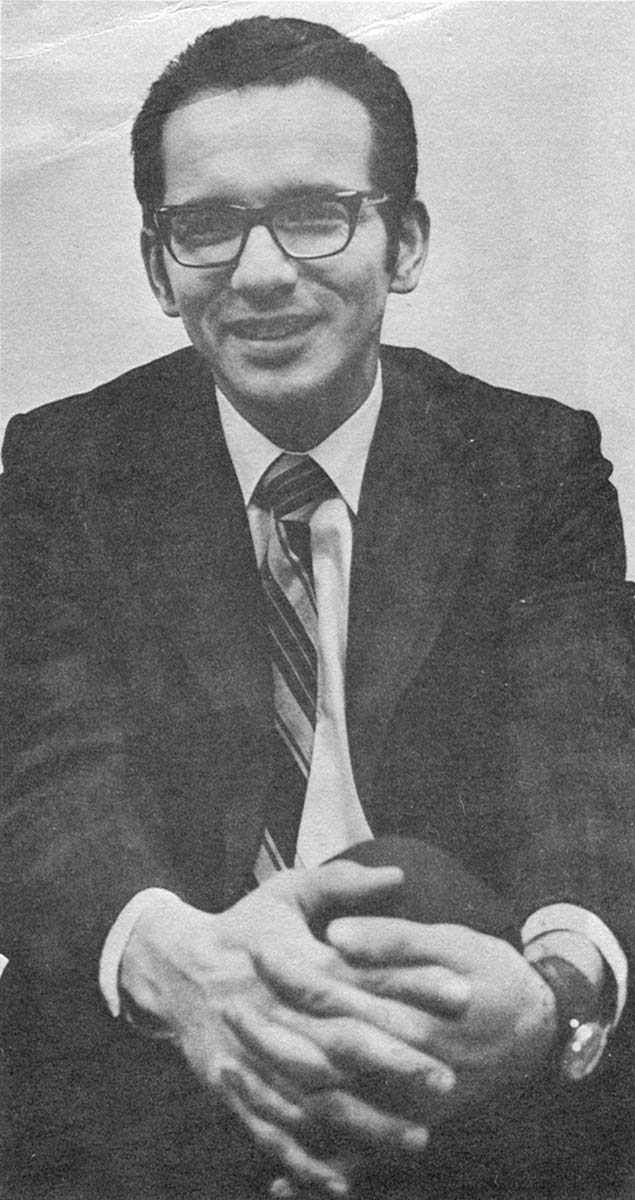

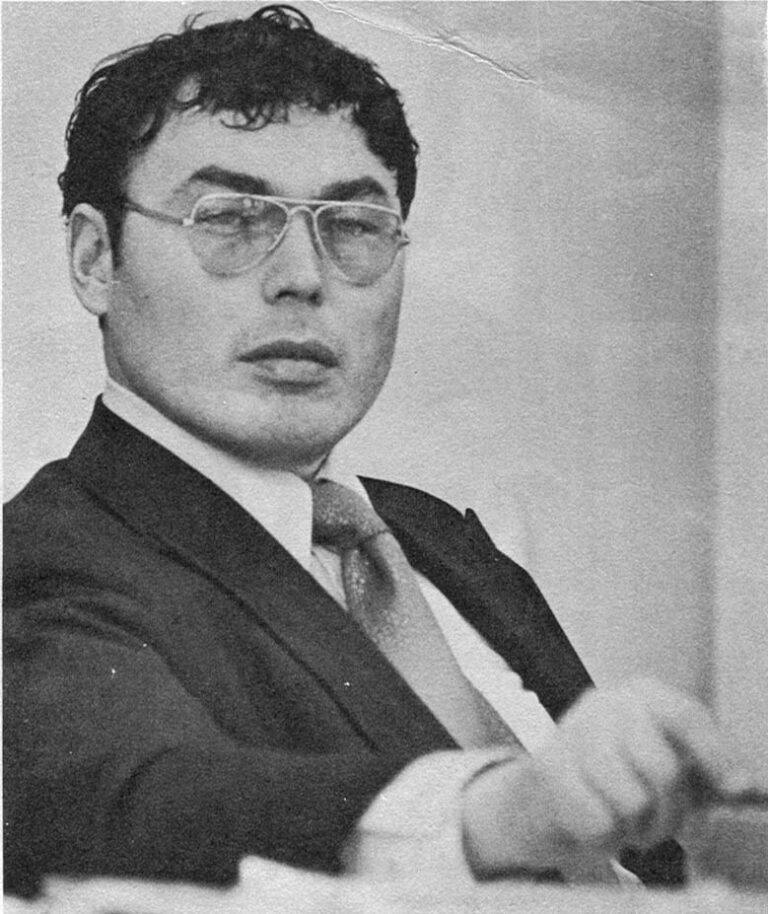

So did two articulate young politicians who would add momentum to the native drive for power. Athabascan Indian John Sackett of Galena, a member of the Republican majority, landed a seat on the influential House Finance Committee and Eskimo Willie Hensley, a Democrat from Kotzebue, buckled down to a House apprenticeship that would later help him unseat state Sen. Bob Blodgett, a non-native.

It was Hensley who pressed the land claims suit of Alaskan natives against the federal government which had never purchased aboriginal title to Alaska. Reading from one of his college research papers, Hensley introduced the issue at a meeting of the Juneau Democratic Club in a cramped hotel basement. Before his first legislative session was done, he mustered strength to pass a bill promising a state royalty to Indians and Eskimos if the federal government would settle their claims.

That same spring a statewide coalition of natives formed to push a federal settlement through Congress. Outsiders predicted the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN) would not survive because it required close cooperation among aborigines who had warred for centuries.

The natives buried their differences, however, and overcame barriers of diversified languages and cultures to gain a billion-dollar Congressional settlement in just five years. In the process, AFN proved excellent training ground for a new wave of native leaders.

The potential of this schooling became apparent when Emil Notti, former AFN president, made a surprisingly good showing as a candidate for secretary of state in 1970. Although hampered by a fear of flying, lack of time and money, Notti pulled 12,759 votes. This was over 2,000 votes more than Charles Sassara of Anchorage who placed third, and only 1,945 votes behind winner Red Boucher. Boucher spent an estimated $100,000 on his campaign as compared to Notti’s $8,500.

Growing coordination among native politicians was demonstrated during the 1971 legislature with formation of a strong voting bloc of rural legislators. Since statehood there had been a fair number of native legislators. Frank Peratrovich, a Tlingit Indian, had even served as president of the Senate, but the natives had generally worked independent of each other.

In contrast, the “Bush Bloc” under the leadership of Rep. Ed Naughton, D-Kodiak, showed a talent for compromise and united solidly on bread and butter issues. By allying itself with factions from urban areas and would-be statewide candidates, it swung the appointment of George Hohman, D-Bethel, (a white with an Eskimo constituency) as head of the House Finance Committee and carried home so much money that the legislative appropriation for the last two years has been known as the “Bush Budget”.

“Unfortunately, Anchorage (Alaska’s largest city) and the bush legislators got the gravy and Fairbanks got only a few bones,” sniffed Rep. John Holm, R-Fairbanks, who represents the state’s second largest city. “That is pure blackmail as far as I’m concerned for Rep. Hohman.”

Sen. John Butrovich, R-Fairbanks, chairman of the Senate Budget Free Conference Committee, agreed. “The chairman of the House committee is from the bush and he thinks bush. The bush was well taken care of. Well enough so I don’t anticipate the bush will have a chairman of either committee for a while.”

Speaker of the House Gene Guess, an Anchorage Democrat, had to dicker with the Bush Bloc to secure his leadership position.

“The Bush Caucus has become extremely effective,” he observed. “Members show mutual concern for each other’s problems but they are extremely selective on areas they want to push as far as a bloc vote, ubich shows good politics.

“This year they’ve developed the ability to deal with administrative agencies. The rural legislator has to be more than just a lawmaker. He has to be a liaison between village agencies and the state government, where urbanites can rely on their city representatives.”

A reapportionment plan set in action by the state just before this fall’s election, wiped out some districts represented by native leaders and pitted several effective Eskimo legislators against one another. Miraculously the natives emerged still holding nine seats, but some good men were unseated in the process and it’s feared that future reapportionment will cut the native delegation.

Even with diminishing membership, however, Rep. Mike Bradner, D- Fairbanks, believes the Bush Bloc will become increasingly effective.

“The rural legislator is forced to be a full-time professional despite the lower wage and he learns more about the system he is dealing with than the urban legislator,” Bradner reasons. “The Anchorage Times keeps urban legislators professing to be part-time and they’re forced to go running home and earn a wage. (Many native legislators manage to live on legislative salary and make politics a full-time job).

“As a result, the rural legislators will know how to get things done better. Knowledgeability and the time they have will outweigh the fact they have less votes.

Eying The Urban Voters

And there is valid reason to question the assumption that the native vote will diminish if reapportionment stands, for natives are toying with the idea of forming a statewide political organization and eying urban voters.

Tailors of the federal land claims bill – fearing a strong, statewide coalition of natives – divided administration of the settlement into regional corporations with no coordinating agency. They also specified these regions could not use settlement funds to dabble in politics, but nothing under the Constitution precludes the natives from uniting politically as individuals.

Discussion of the subject came up last fall at an informal meeting of a few AFN members who passed the hat on the spot and collected $200 to start things rolling.

“We’re not talking in terms of a native party, exactly,” explained a participant who declines to be named until the organization is formal. “What we want to do is encourage talented natives to run for office, help with campaign funding and coordinate native endorsements.”

Since that time AFN has been embroiled in an internal political struggle for its own survival; plagued with funding problems, lack of backing from the regional organizations and, more basically, clarification of its duties and powers as a coordinating agency for the regionals. Doomsday groups are predicting it will not survive but regional leaders seem to be in agreement that they need statewide coordination and that they will be able to unite again when they need to, as they did for the claims settlement.

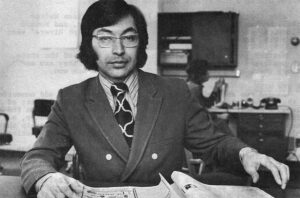

Morris Thompson, an Athabascan who is area director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs for Alaska, believes his native people can pick up even more political power in the process.

“What we’ve got to do is get our people to run out of Anchorage and Fairbanks . We’ve got to be aggressive. Five years from now with rapid growth in Anchorage and Fairbanks, we’re going to have a large number of natives that vote with the Bush Bloc. Like the midwest, our people are assimilating into urban areas.”

Rep. Chuck Degnan of Unalakleet promises, “We’ll be becoming it a lot more active and that will have impact on how politics shape up.”

Anyone who doubts it should study the record of Degnan and his Northwest delegation at this year’s state Democratic Convention. With expert maneuvering, a strong Bush Bloc allied with a young Ad Hoc delegation to oust old party regulars. Eben Hopson, Eskimo leader from Barrow, used his position as temporary chairman to call the shots and tailor a party platform to the needs of the bush.

“Unless the natives organize politically on a statewide basis we’ll never realize the true strength we can exercise in dictating politics and programs,” maintains Byron Mallott, Tlingit Indian and Alaska’s first native commissioner (Department of Community and Regional Affairs).

In 1970 Mallott and other leaders attempted to put together a native organization along the lines of COPE, the political arm of the Teamsters, and give endorsement to a Democratic candidate for governor.

“It pointed out that, no matter how unified we are on bread and butter issues, we break down as quickly as any other citizens when it comes to a political issue,” he recalls. “But I got so involved if someone had come up with $4,000 I’d have quit my job and gone with it.

“Not enough people really understand the political process in the state. Many people view native power on specific issues. Let’s say a village wants a water system. They scream to their Congressional delegation, write letters to the governor. When they get some action they feel pretty good. Miracle of miracles! They get a water system but that’s the extent of native power.

“Most of our power, latent forces we have yet to develop. We’re kicking it around right now. But making them understand at a village level is going to take some selling.”

Far-thinkers figure that if each Alaskan native kicked in $30 for a political contribution they would have about $600,000 for a full time staff and campaign funding. Plans are now on paper for such an organization and – although at the moment leadership is necessarily preoccupied with management of the claims settlement – it could become a reality.

Currently John Borbridge, Tlingit leader and head of Sealaska, their regional corporation, is more concerned with native participation in local governments than in statewide organization. Under the federal settlement some native lands must go to municipalities and if the natives have no say in their local government they will lose control of these lands.

“It will be necessary for us to control our community and municipal councils,” Borbridge warns. “We must get moving now. our future assets will be effected. We’re being forced to explore ways to become more politically active.”

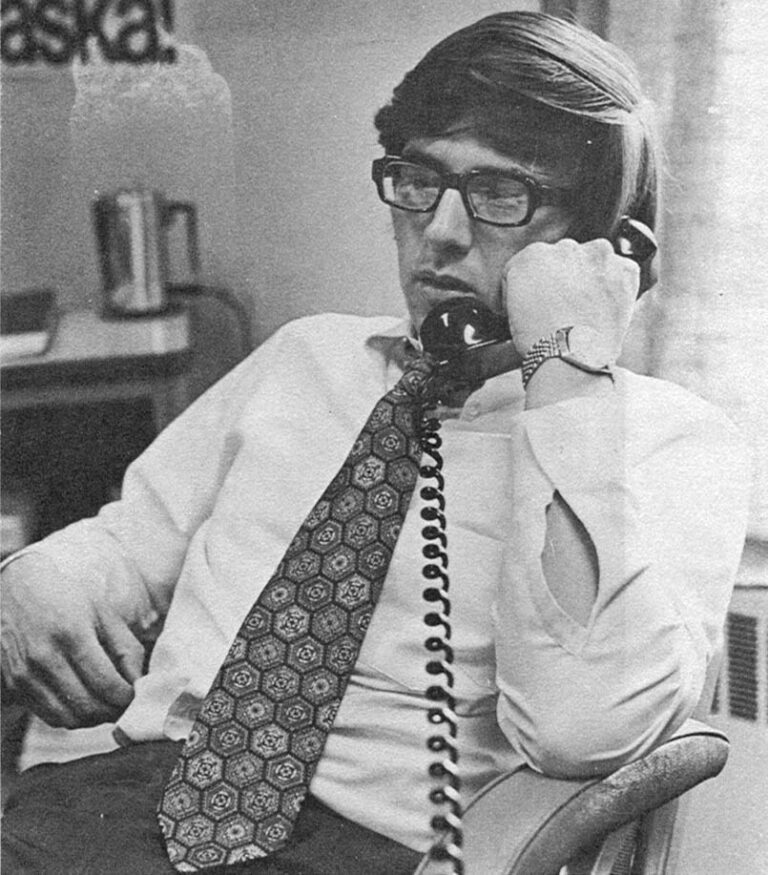

Emil Notti, who is currently waging a strong fight to win the U.S. House seat vacated when Nick Begich was lost on an airplane flight this winter, does not think in terms of a statewide native party or – more surprisingly – in terms of parties in general. Although he is chairman of the Alaskan Democratic Party and its chosen candidate in the special election he believes that the average native voter will not go with the party.

“He’s going to go with the man. I joined the party in 1967-68 . The Democratic party because it seemed to have less special interests…but it’s no Utopia.”

He feels reapportionment will eventually cut the size of the bush delegation to the legislature and that it will not be easy to get native representatives elected from urban areas.

“It can be done but it’s just going to be tougher than blazes! We’ve got the talent available. Whether we can use it or not is the question.”

But he added that his people have a good many experienced young leaders, which must be considered a long term asset for the natives.

Other Minority Groups Watch

Other minority groups – the Indians and Eskimos of Canada; Hawaiian natives; Australia’s downtrodden aborigines; the Ainus, a Caucasian minority in Japan – are watching the Alaskan native movement carefully, trying to assess just what has made it work when similar groups such as stateside Indians, have failed to rally any real strength.

Looking back, Willie Hensley will tell you with a smile, the new wave of native leaders he came in with back in 1966 were “very similar to the gathering of demigods in Philadelphia in 1776.”

Seriously, he speculates, “I don’t think we had anything going for us except the fact we were standing in the way of progress and the fact the government had never legally taken our land.

“I think we all recognized the predicament we were in. The villages more or less agreed and they gave us the latitude to go after the settlement.”

He is uncharacteristically dubious about the future of his people at the moment, perhaps because he has just taken over as head of the AFN and is struggling to put it back in a position of power as a coordinating agency for the regions.

“I wish I could be more optimistic. Say in 20–30–40 years I believed our people would be prospering, pulling together, developing leadership, contributing to the state….

“I think we have bought some time and maybe we’ll develop to that point. We can protect ourselves for a period of time because of the power of money. It all depends on whether we can make the transition from political power without economic power and still be able to make decisions with some political power and great economic power. If we get more depth in leadership, I think there’s a chance.”

Notti assesses the Alaskan native’s advantage as mainly a move at an opportune moment.

“It was a time in history following right behind the civil rights action of the 50s and 60s, an age of wide communications, when the United States stood to be looked at by the world. It professed to be an equal opportunity government. It really couldn’t, in view of what was going on elsewhere in the world, treat the Indians any differently. And in my point of view it was a fleeting time. If we didn’t get it very quickly the time would have passed.”

Whatever combination of elements, Alaskan natives have moved to power with unprecedented speed, and whether or not they continue to gain force, most leaders agree with John Borbridge when he says, “The native vote is simply not going up for grabs any more. I don’t think we’re ever going to see that happen again. Whoever is going to take a statewide election is going to have to deal with the natives. Nobody can ever take us for granted again.”

Received in New York on February 12, 1973

©1973 Lael Morgan

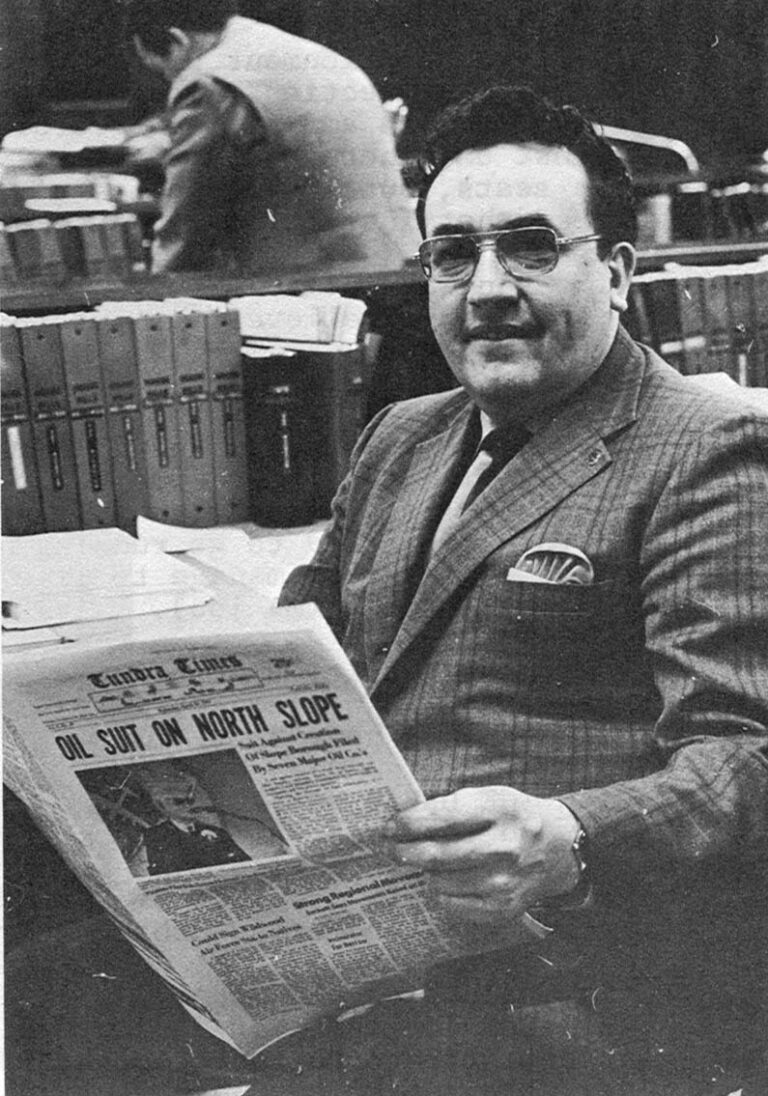

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.