Angoon, Alaska December 8, 1972

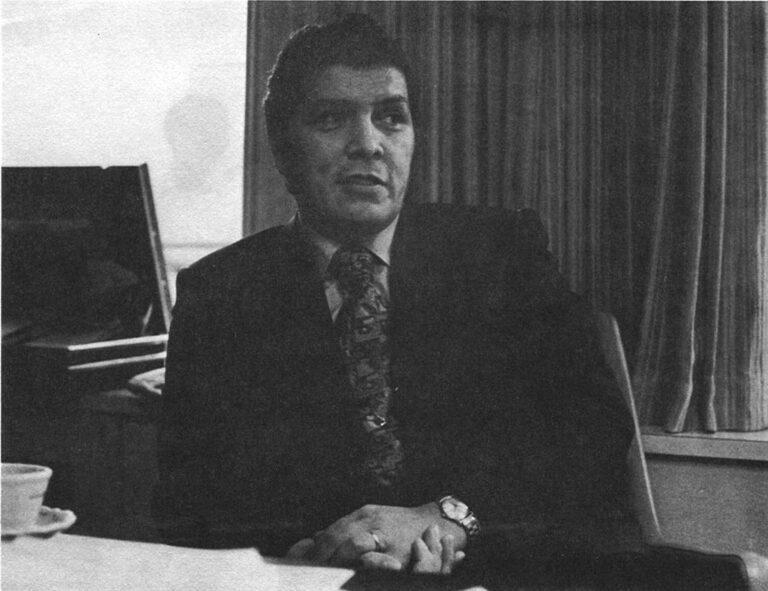

At the top of the political totem pole is John Borbridge; urbane, well-educated, city-bred chief of the Tlingit Indian people. Many believe him to be an inspired leader. Others charge he is a politically ambitious self-seeker; a “God Father.”

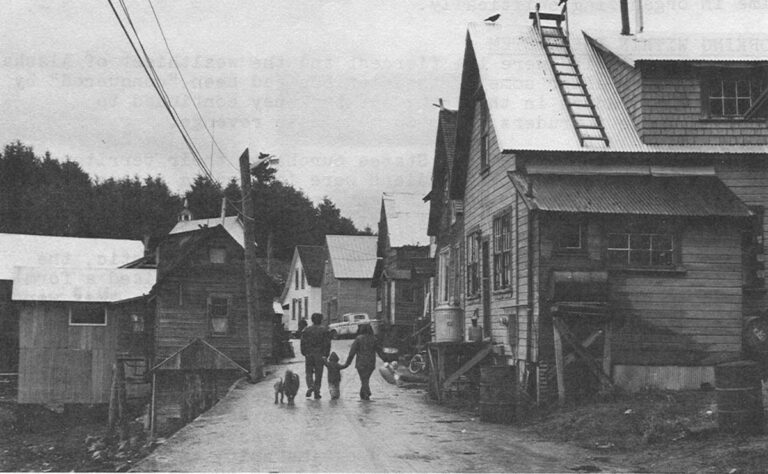

At the base of his totem are 18 Indian villages in Southeastern Alaska; all electrified but in varying degrees of modernization otherwise. Angoon, an isolated fishing community of 400 on Admiralty Island, is at the bottom; reporting the lowest median income in Alaska ($2,154 as compared to neighboring Juneau’s $16,073 according to the 1970 U.S. Census), in a section of the state where poverty is not generally a big problem.

Some observers believe there is a serious and growing gap between native leaders and the disadvantaged villages they represent. The concern is not limited to the Tlingits, but shared by widely varying groups of natives throughout Alaska. Their leaders were sophisticated enough to unite and push a billion dollar, 40 million acre land claims settlement through the U.S. Congress – and to deal with the complexities of the white power structure and win. But can these same leaders remain in touch with the remote, backward villages that are their power base and put the gains to good use?

Angoon versus Borbridge is a case in point, because of the contrasts involved and because these people were well ahead of their time in organizing politically.

Working Within The System

The Tlingits were the fiercest and the wealthiest of Alaskan natives. Even after some of their tribes had been “conquered” by Russian fur traders in the 18th Century, they continued to annihilate the intruders and reap merciless revenge.

By the time the United States purchased their territory from the Russians in 1867, these Indians were (according to a government report) “somewhat tamer, but insolent and disrespectful,” for their tribal system was still intact and through it they had power.

Unlike the majority of natives who were socialistic, the Tlingits understood capitalism because they had practiced a form of it long before the whites arrived. For this reason, they were the first Alaskans to use the whiteman’s system by working within it.

They were also the first to talk land claims, suing the U.S. government in 1936 for $80 million in lost timber lands. The federal court haggled over the case three decades, finally awarding the Indians a paltry $7.5 million (less than 46.8 cents per acre) but Tlingit leaders accepted the decision reasoning the money might be used to further a statewide land claims suit, the recent settlement of which will bring them an estimated $83,160,000 to $144,760,000 and additional lands.

Angoon Tlingits claim they were never defeated by the Russians. Their village was bombarded by the U.S. Navy in 1882, however, when the Indians tried to avenge the accidental death of a member of their tribe employed by the local trading company. Such procedure was perfectly legal under Tlingit law, but the Americans refused to make settlement of the traditional workman’s compensation of 200 blankets, destroying part of the village and its winter food supply.

Angoons still tell the story emotionally, as a first person account, and are belatedly suing the U.S. government for damages, however the incident caused them to rethink their fighting strategy, which eventually served them well.

“About 1918-1920 we decided, ‘Let’s start living like the white people,”‘ recounts Albert Frank, 70, local president of the Tlingit-Haida organization which administers the 1965 timber settlement. “We started a town council and improved our living conditions in Angoon. We built a path for our younger people.

“They passed a law the Indian was going to have local, municipal Indian self-government. We can arrest each other but cannot arrest the white man. Can only complain to Juneau….

“Pretty soon, 1921, we join Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB, the organization that lead the Tlingit fight for equal rights). Up to that time no school instructor. Through the town council and ANB we demand school be given here.

“Put up coal oil street lights. Then, after, build town hall. Think about electricity. Bought a little motor that throws a lot of light. Everybody happy. Later on people decided they wanted a bigger light plant. Raised the money in just one evening….

“In over 50 years from the time I could remember, I’ve seen a lot of change taking place in Angoon and all for the better.”

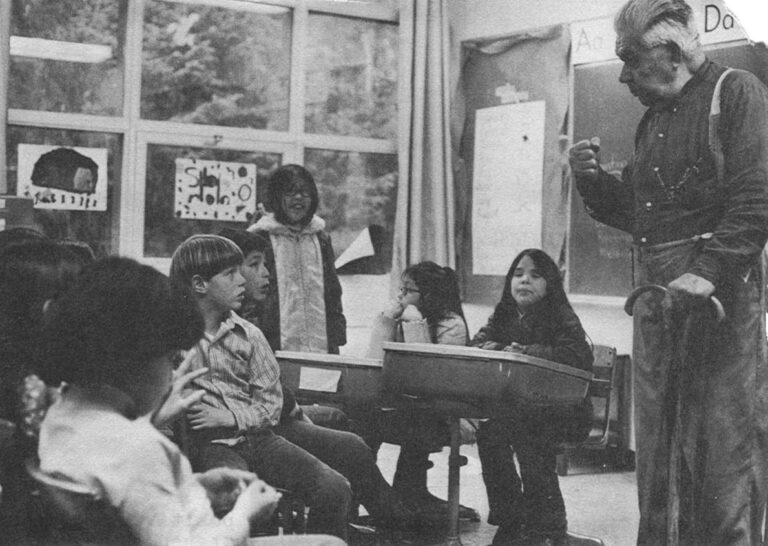

Presbyterian missionaries forbade the speaking of the Tlingit language in their school and forced Angoon residents to remove colorful tribal symbols painted on their houses. The awesome totems Tlingit elders had carved from towering spruce trees began to rot and villagers buried or destroyed them, lest they fall into unfriendly hands.

Outwardly, they lived as white men, but their tribal system remained so strong that even today a clan function will outdraw a city council meeting.

And the village prospered, producing strong leadership and keeping a firm financial footing. In 1950, negotiating a loan from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), residents bought a cannery at near-by Hood Bay, insuring their own employment. The cost was $226,000 and they managed to get it half paid off in the first year, even though fishing was poor.

But the cannery burned mysteriously and with it went expensive gear belonging to the fishermen, throwing the fleet hopelessly in debt.

“We suspect the fire was set by people who didn’t want to see the Indians get ahead but we never could prove it,” one villager said. “The BIA said we’d be reimbursed for our lost gear but we never were and we couldn’t get them interested in helping with another cannery.”

Today the Angoon fishing fleet – 14 seiners and 40 trollers – is a miracle of floating dry rot. The fishermen’s indebtedness, after the last two disastrous fishing seasons, is said to be in access of $1 1/2 million and some of the boats can no longer get insurance.

Frank Jack touched on the feeling of hopelessness of such debt, as he headed for the boat harbor to pump out his “St. John.”

“The boat has got a lot of dry rot. Will cost about $60,000 to replace, and I don’t know how…. Seems like since the Hood Bay fire we’ve just been drifting.”

In The Broom Closet

Angoon’s drift came at a time when neighboring Tlingit villages began to prosper. Yakutat, also a fishing community, landed a million dollars in federal funding to build a cold storage plant. Hoonah became an official stop on the state ferry run and Angoon people watch with envy as the ship goes by their village, enroute, but doesn’t stop. (Scheduled air service to Angoon is $42 round trip from Juneau. It is the only way to get to the island except by fishing boat.)

“I’m beginning to see what Yakatut is getting…. What Hoonah has been getting and we’re getting nothing,” Cyril George, new Angoon mayor observed at a recent city council meeting. “I feel like Tennessee Ernie Ford. I owe my soul to the company store.”

About the only thing Angoon did get was bad publicity. In 1957 the village came to near-hysteria when an imaginative 16-year-old Tlingit girl declared herself a witch and began putting spells on people.

“I think it was just cabin fever,” recalls Mrs. Marie Day, who served as acting U.S. Commissioner at a public hearing on the incident. “She’d apparently hexed some children. There was a lot of measles and flu in the village that winter and this child happened to die. It was weird. Nothing of it really made sense. They were burning fires at midnight and killing cats….”

The case made national headlines which hurt the village nearly as much as the cannery fire. Then, this summer, an itinerant preacher stirred the town to similar frenzy, holding rock services, mass baptisms and icon burning sessions and leaving town with from $9,000 to $11,000 in his collection plate.

“It really hurt Angoon. It blackened the face of our village,” a worried resident reported. “When our delegates went to the Alaska Federation of Natives convention (a statewide native meeting) they asked, ‘Is the Angoon delegation here? If you don’t see them here, you go down and look in the broom closet.’ That’s cruel.”

There were some quietly positive things going on in the village, however. Residents mustered early to push for statewide settlement of native land claims, staging bake-off and rummage sales to get its representatives to meetings.

Village elder, Sam Johnson, spoke briefly but well at the first Senate hearing on the claims back in 1969: “Our children growing up are forgetting the language. They are becoming more like a white man. They need the education. They need their homes in Angoon. We need support to help our people over there because the land we have, we are loosing….”

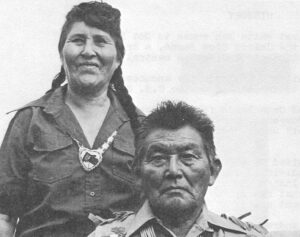

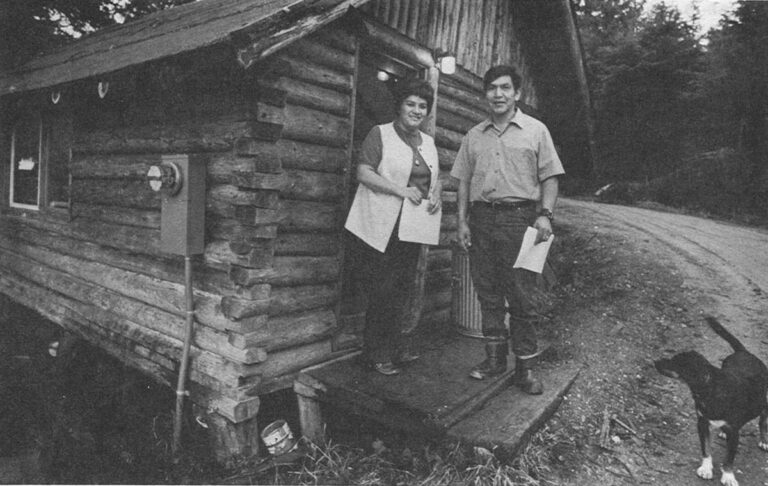

And Lydia George, housewife and mother of 11 children, grew impatient with the slowness of the movement and, with only a fifth grade education, got herself elected to the Tlingit-Haida Central Council, traveled widely and worked with her husband and the old people on land selection. In 1966, combining forces with leader John Borbridge, she began mapping land selections Angoon would claim. Something other villages only began to think about last year.

When her work was finished, Mrs. George was voted out of office on the grounds “she lacked education and was a woman.”

“You rest, and I’ll take up where you left off,” promised one of her sons who is now studying law.

Education is a plus for Angoon, too. The village has a strong Head Start program for pre-schoolers, Tlingit language courses in the grammar school and 20 youngsters currently enrolled in college.

“If the State Operated Schools would put a high school in Angoon, we figure we could get half our college kids back home to fill the teaching jobs,” plots Mayor George.

“Jobs” is a magic word in Angoon for 95 percent of the residents are now on welfare.

“Welfare is so much a part of the income around here I sometimes feel we should take out withholding and Social Security,” jokes Judy George, city clerk. “But really, it’s no joking matter and we want to phase it out.”

Credit can be given the village for fighting to retain some pride while on dole.

“There’s a lot of people here that need the money but they’d rather work for it,” explained Matthew Fred Sr., village social aid. “In 1960 we started negotiating with BIA, trying to get our general assistance money put into a work program. They were reluctant for a long time but finally we started in the fall of 1969.”

Under the work program, welfare money is used as salaries for enterprising village public works programs. The jobs are shared by villagers who are paid according to their family needs. The program maintains water lines, buildings and roads and cares for old people.

Coming Of Age

Another government program, the Public Employment Program (PEP) which provides for hiring of a city clerk and social worker, may well mean a reversal of Angoon’s fortunes as a municipality.

Before PEP was made available last summer, the mayor was forced to carry on city business out of his own home and pocket. Records were scattered among city council members and there was little coordination of city business.

Under the new program, Mayor Matthew Kookesh hired Judy George, a Juneau Tlingit, as city clerk and it was a sound choice. Before her recent marriage to Cyril George, a widower, she had been one of the top executive secretaries in the state capitol. She brought to Angoon a thorough knowledge of the workings of state and federal government agencies; quickly unscrambled city correspondence and, with Kookesh, began investigation of possible funding for village programs.

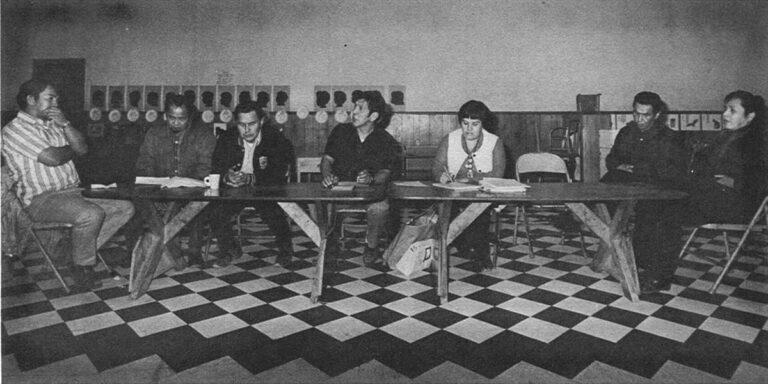

They had already established a Youth Corp and adult education program and nailed down the promise of 30 low income houses from Tlingit-Haida, when Kookesh died last month. His job has been assumed by Cyril George and the lights in the city office continue to burn late as the couple drums up grant proposals.

Last month, George held the first public council meeting villagers can recall in a long time, and it was well attended. Priorities of need were established by the villagers, and there was a ghost of the spirit of 1950 when the cannery came into being.

What the villagers say they want is the same thing they’ve asked for all along. Not welfare programs or free houses, but a chance to make their own way. Today they’re thinking in terms of a cold storage rather than a cannery. They seek a breakwater to protect the harbor and a viable means of transportation; namely the state ferry. All these proposals seem feasible. Especially if Angoon can gain borough status which would entitle it to collect stumpage fees from the timber-rich island on which the village is situated.

United Front

But to get it together, Angoon must present a united front and gain more respect from area-wide native representatives and some of these men have written the village off, long since.

“It’s a real loser,” one of the lesser lights confided to me. “Angoon has been out of it for ages. We don’t pay any attention to it.”

“Some of them think they’re gods, or something,” fumed a local Angoon politician. “We all came up from the same place about the same time. At a recent Tlingit-Haida meeting one of them had the nerve to tell us only he and John Borbridge were qualified to sit on the Alaska Federation of Natives Board. Well, we’ve got some good people, too. And we haven’t got all those kids going to college for nothing. They’re going to be surprised!”

Listening To The Elders

Leader John Borbridge, whose recent election was not exactly a “shoo-in”, is quick to proclaim awareness of the power his villagers hold.

“It’s easy for educated leaders to become satisfied with communicating only with each other,” he admitted. “They forget about their constituency. One thing I did was get the support of the older people. They chose to accept my leadership because some of them didn’t have the education. But I listen to the elders’ advice, and many of them have worked to teach me…still are. I think I really have a feeling for the land, the culture and the way of life.

“There is a rising pride of culture in us. A knowledge of who we are as a people. The people who have fought hard to retain their land base are the people who still live on the land and use it.

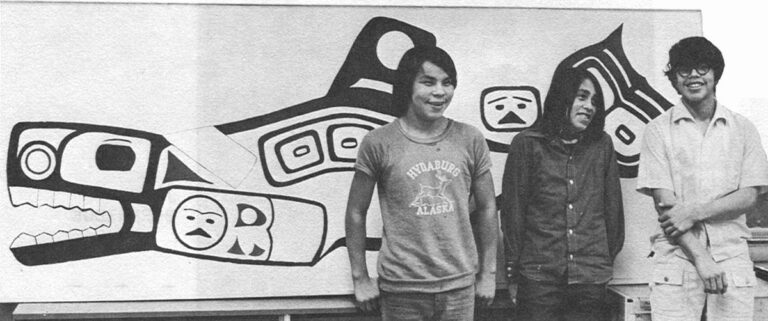

Tribal traditions are still strong in Angoon

“I like to think of myself as culturally disadvantaged. Although both my parents spoke Tlingit, I was brought up to speak only English,” he recalls. “My father said he made a very determined choice. That it was a tough world and I was going to have to compete all the time, so he focused on formal education.”

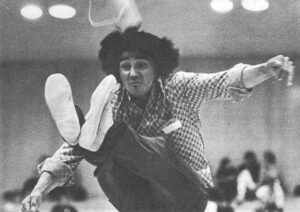

Borbridge was educated in Juneau High School, went to Sheldon Jackson Junior College (an Indian school in Southeastern Alaska) and got a B.A. in Political Science at the University of Michigan. He did graduate work and then took an athletic coaching job at Juneau High School.

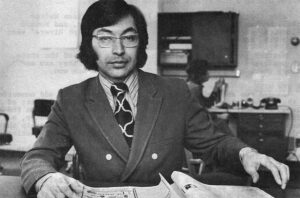

He entered native politics officially as the first elected president of the Tlingit-Haida organization after the 1965 court settlement. Today he heads Sealaska, the regional corporation formed by the Tlingits to administer their federal land claims settlement.

Despite his professed concern for immediate village needs, however, he is currently engrossed in long-range planning to insure preservation of the claims settlement capital.

“We hope to approach an over-all planning program for Southeastern with the Tlingit-Haida organization” he said. “We’re pressed by short term needs. Better housing…better standard of living. But we’ve got to look beyond these needs. The initial steps will be profit-seeking investment. We may look beyond the region; maybe beyond the state.

“Part of our money may have to go into areas of capitalization for native businesses. There’s a lot of businesses we’d like to see get off the ground. We know that venture capital is hard for them to find. And if we don’t provide it they’ll say, ‘What’s the difference between your organization and the bank? They both say no to us!”

But generally he speaks in terms of investment institutions, outside expertise, Chase Manhattan. He brightens at the idea of a native-owned, statewide banking institution. His concern for the villages is directed more in safeguarding what they have now than initiating new enterprise.

There has been criticism on a local level because Tlingit-Haida has continued to retain lawyers in Washington, D.C., hired originally to shepherd the land claims legislation through Congress.

“I see the need for Washington counsel increasing rather than decreasing,” Borbridge maintains. “Not only to work on land claims legislation but to protect our assets and insure the services which the Alaskan native people are now interested in, continue. We need counsel in Washington now, even more than before because we have assets to protect.

“And it’s really important that the BIA or the Office of Education of the Office of Health and Welfare be prevented from making harmful cutbacks.”

Different Points Of View

Borbridge’s salary as president of Sealaska is $35,000, which is fairly modest in view of what some regional corporation directors are receiving in other areas of the state. His travel budget and per diem are $8,500. And his views don’t differ much from those of other regional leaders (although he may be a trifle more conservative). Most of them dread the idea of dissipating their capital on social services and economic development in areas where the profit margin would be questionable.

But his philosophy – or any regional director’s philosophy along these lines – can’t be expected to generate too much enthusiam in a village that can’t afford to pay a mayor or business manager and has a median income of $2,154.

According to the land claims settlement legislation, Angoon will eventually get a share of the royalty revenues received by its regional corporation, but estimates on the amount of this money are vague and it may be long in coming.

To date, out of the $7.5 million court settlement, the village has received $250 per capita grants for its older residents and $2,400 for city planning. They have been promised but haven’t received $26,000 for city planning this year and a housing program that was to be ready for occupancy “by Thanksgiving” but hasn’t even started.

City officials are becoming a little cynical about such bonanzas and the feeling was reinforced last month by a speech given at the ANB convention by Clarence Jackson, president of Tlingit-Haida.

“Seven point five million dollars (the court settlement) is really not a large sum of money,” he warned. “We must try to preserve these funds and only use them as seed money to attract other funding.”

Well, Angoon is beginning to get that message. In fact, health aid Barbara Johnson put it well when she was investigating funding for a much needed alcoholism program in the village.

“Nobody’s going to help us,” she decided. “We’re going to have to help ourselves.

And with the thought comes a new and refreshing idea. That, although Angoon is on the bottom of its political totem pole, it might have some power to help with the carving. And native leaders who write the village off as a long gone loser, may soon be surprised to hear the sharpening of chisels.

Received in New York on January 2, 1973

©1973 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.