This year’s conference on Coal and the Environment, sponsored by the National Coal Association, the industry’s lobbying group, provided the annual showcase for promotion — both of the industry, and the manufacturers who serve it. Purveyors of products ranging from executive helicopters and the latest and largest earth-moving equipment to polished charcoal briquettes gathered at the Exhibition Center in Louisville, where salesmen in double-knit suits and their female counterparts in hotpants hawked the most recent developments in mining technology.

Meanwhile, the auditorium leading off the main hall were filled with government and industry representatives listening to discourses by experts on coal mine drainage, mined land reclamation, mine refuse disposal, and emission control. Not the most fascinating program for laymen, and yet one of some interest to most observers. Opinions did surface — often inadvertently — suggesting that coal development is not uniformly beneficial to all areas, and reclamation is no certainty.

A spokesman for the economic research service of the United States Department of Agriculture, Frank H. Osterhoudt, addressed himself to the economic and social impacts of coal development in the Northern Plains of America, where agriculture has always been the dominant economic base.

“Local people are concerned whether they could be employed by the new industry, and receive the higher wages paid,” Osterhoudt said. “Coal gasification plants would employ mostly skilled and professional personnel…. Very few of these positions would be filled by local people…. The case of an electric generation plant is similar to a gasification plant. The direct effect of coal activity on unemployment is mixed. Where there in no manufacturing sector or other pool of skilled and professional workers, there could be immigration even to an area experiencing relatively high unemployment. At least some local labor will be drawn into the semi-skilled jobs….

“Agriculture is the present economic base of much of the Northern Great Plains. Farm equipment operators will have a direct alternative opened to them by mining and construction. The cost of farm and ranch labor will rise, requiring agricultural businesses to change both capital investments and management. Farm and ranch consolidation will probably accelerate as some operators take the opportunity to transfer out of agriculture, and others are forced out.

“Energy processing competes for water. In the coal area of the Northern Great Plains, water is scarce, with an average annual precipitation ranging from less than ten inches to seventeen inches. Coal mini requires little water directly, but may disrupt the ground water, especially in those areas where coal seams are aquifers. Some water may be required for reclamation. In coal-fired electric power generation plants, water is consumed in cooling…. Since energy companies can afford to pay considerably more for water than can agriculture, this could cause major agricultural adjustments. It may affect other industry as well….

“One empirical study shows that ‘people pollution’ is of more common immediate local concern than negative effects on the natural environment. A second study shows that most residents, regardless of occupation, were interested in preserving their natural environment.”

Those observations are hardly revolutionary, and yet for them to be officially sanctioned by the National Coal Association was something of an achievement.

Most of the papers presented at the conference dealt with mining technology, rather than with reclamation, or the social impact of coal development. At the luncheons and private sessions during the conference, the rhetoric of coal was familiar. Coal makes the difference, it was said, between traveling first class through life, and “freezing in the dark.” But there did emerge a grudging recognition of the industry’s responsibilities to people and the environment.

One important notion discussed was that of air quality. Industry spokesmen have repeatedly claimed that stringent air quality standards were preventing the full development of coal, and adding significantly to the present crisis of energy supply. This question was addressed by Secretary of the Interior, Rogers C.B. Morton, at the main NCA convocation, and caused some surprise.

“Some observers tell met” Morton said, “that we are faced with an either-or argument — either we change the regulations to allow the burning of dirty fuels and pollute our air — or we go without energy.

“I don’t see it that way. I’m just naturally suspicious of either-or arguments. I am certain that we can continue to work toward the goal of clean air. Already there are significant advances in stack technology, and we should not give up our efforts to achieve this goal.”

Morton added that “we may have to stretch out the time frame,” meaning that compliance with clean air standards may be permitted later than the present deadline.

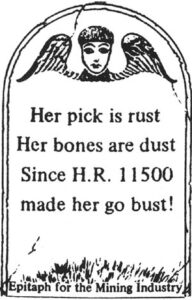

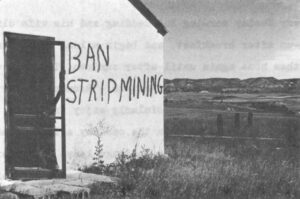

Morton said of surface mining regulations: “Opinions may vary as to the bill that may finally emerge from the congressional conference committee, but there is little doubt that it will contain strong land reclamation provisions. Tour industry, I believe, must recognize that mined land reclamation is part of the price we will all have to pay to achieve public acceptance for coal as an energy source.

“This is your proper role and, from the environmental viewpoint, the political posture of this country will not permit otherwise.”

The message was clear: whether or not the industry, and its supporters in the departments of Interior and Agriculture, really cares about such questions is immaterial. The climate of opinion in America will require judicious and responsible coal development, and energy supply.

Morton went on to assure the conference that coal would be in great demand for at least fifty years. The reasons he cited were population growth, increased demand for energy fuels, the concentration of oil supplies, and the economic advantages of coal.

“Another reason why the future of coal in the United States is so bright is tied up with international balance of payments deficits. Our national economy is suffering a hemorrhage — bleeding off twenty-one billion dollars in 1974. I mean that we are importing forty-two billion dollars worth of resources; oil and a1l other minerals. At the same time we are exporting twenty-one billion dollars worth. That leaves us out of pocket some twenty-one billion dollars per year.

“This obviously cannot continue. Oil alone is costing us three million dollars per hour, in money, which is flowing out of this nation and into the Middle East. That simply cannot continue. When we buy a million dollars worth of foreign oil, this nation loses one million dollars. When we buy a million dollars worth of coal, we keep that million dollars in the country….

“In my opinion, the National Coal Association is not worth its salt if it is not actively engaged in the planning and design, along with the electric power industry, the transportation sector, and other basic users, of complete coal-use systems.”

Many industry spokesmen were concerned about leadership in the energy field that the Ford Administration would provide. In succeeding newsletters I will discuss this aspect of energy in America, as well as sources other than coal, particularly oil.

Received in New York December 3, 1974

©1974 James Conaway

James Conaway, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Conaway and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.