Southern Mexico’s states of Chiapas and Tabasco are low, swampy areas at the base of the Yucatan peninsula that float on rich deposits of oil. The most recent, and most significant, discoveries have been made here, and production from the new wells has grown almost one thousand per cent during the last two years. Mexico plans to earn almost $500 million in oil and gas profits in 1975, and the country has gained the coveted position of oil exporter.

In celebration of the thirty-seventh anniversary of the creation of Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), Mexico’s nationalized oil industry, a ceremony was held by PEMEX this spring in Reforma, Chiapas. It was attended by President Luis Echeverria, and Carlos Andres Perez, the president of Venezuela, another oil producing country of the Americas.

In celebration of the thirty-seventh anniversary of the creation of Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), Mexico’s nationalized oil industry, a ceremony was held by PEMEX this spring in Reforma, Chiapas. It was attended by President Luis Echeverria, and Carlos Andres Perez, the president of Venezuela, another oil producing country of the Americas.

The elaborate preparations, and the apparent prosperity of those attending, stood in sharp contrast to the more elemental conditions of life throughout Mexico. It is still among the poorer nations, with a vast gap between the rural poor that make up more than half the population, and a small middle class faced with rampant inflation. Mexico hopes that oil may greatly affect both classes.

In his speech at Reforma, the director general of PEMEX, Antonio Dovali Jaime, said that Mexico had decided “to overcome the obstacles naturally attached to a highly technological industry, and to compel the petroleum producing world to rectify the poor opinion held for a while regarding our capacity to administer our own wealth.”

Mexico now takes its role as a producer of hydrocarbons seriously, and does not intend to conform to the opinions of other nations — including the United States. Whether or not Mexico plans to join the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries is uncertain, and officials refused to discuss the subject with reporters. But it is certain that Mexico will not turn down membership in OPEC just to satisfy the desire of the United States to break up the oil cartel.

Proof of Mexican independence has been its supplying of crude oil to Cuba. Mexico has granted the Cuban government $20 worth of credit, and this may be expanded to $80 million during the next two years. Also, Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, and the Soviet Union have formed a trading company to sell crude oil and petroleum products to countries that have no oil production.

Within a decade, oil is expected to have a revolutionary impact on Mexico’s economy. Money earned from oil and oil-related exports can be reinvested in Mexico’s schools, agricultural programs, rural electrification projects, and roads. Mexico may be one of the fifteen wealthiest nations in terms of output, but half its people live on the land, and agriculture accounts for only ten per cent of Mexico’s output. Oil money will help close Mexico’s foreign trade deficit, which was more than a billion dollars in 1974.

Mexico plans to export not only crude oil, but also gasoline, diesel fuel, petrochemicals, plastics, and other processed goods, which will be more profitable than shipping out only crude. Three new refineries are to be completed before 1980. Last year Mexico suspended imports of gasoline, diesel and fuel oil, and began to sell their own hydrocarbon surpluses. In 1973, 23 million barrels of crude had to be imported, and 23 million barrels of distillates and other petroleum products. These imports were down to six million barrels of crude in 1974, and 16 million barrels of other products. So Mexico’s reversal of imports was dramatic.

It has been known for many years that Mexico had large reserves of oil, but it required the sudden, steep rise in the price of crude oil to bring about quick development of new fields. When the oil industry was nationalized in 1938, oil production in Mexico had actually declined over the previous ten years. In 1974, 238 million barrels of crude were produced in Mexico, and two-fifths of that amount came from new wells. Officials hope crude oil exports will reach 75,000 barrels a day this year.

Before the new discoveries of 1974, Mexico was known to have about 0.6 per cent of the world’s known oil reserves (Venezuela had 2.5 per cent, and Canada had 1.7 per cent). But that estimate has been revised. Rock formations below the surface of the land in Chiapas and Tabasco extend one hundred miles out into the Gulf of Mexico. An offshore well drilled near Campeche, on the western coast of the Yucatan, has encouraged experts, who believe the offshore pool might approach the capacity of those off the coasts of Louisiana and Texas.

Oil reserves are also known to exist in the state of Veracruz, and PEMEX engineers are confident that another discovery will soon be made in Baja California, in northwest Mexico. Major efforts to find oil along the Pacific’s continental shelf failed, but on-shore development looks promising. One problem in the development of proven fields is transportation of oil and gas from the fields to industrial areas. The new refineries are being built outside of Monterrey, and north of Mexico City, but refining capacity in southern Mexico is insufficient. An ambitious plan is underway to build another refinery in conjunction with a pipeline across the isthmus from Tabasco to the Pacific coast. This is the narrowest part of Mexico, and next to Panama, the narrowest point in Central America. The area around Salina Cruz on the Pacific is a major port, and the pipeline would connect it with the fields to the north.

Natural gas production is also increasing. Gas was first discovered in northeast Mexico, near the border of the United States, and this led to the industrial development of the corridor between Chihuahua and Tamaulipas. Later gas discoveries were made further south, and a refinery at Salamanca increased industrial production. Other refineries are located at La Venta, and Ciudad Pemex, near Villahermosa in Tabasco. The high ratio of natural gas and ethane in the crude oil produced in this area, recovered in conjunction with the oil, has made it feasible to develop the gas for industrial and domestic use, and a pipeline is planned from Cardenas to Villahermosa.

Mexico consumes most of its own oil. Daily crude oil production is 672,000 barrels, and in order to have more of that production avallabl6 for export, Mexico raised the price of PEMEX gasoline twice within a year, which now stands at about ninety cents a gallon. The revenue will be funneled back into the government monopoly-drilling program, and into refinery construction.

In spite of surplus oil, and Mexico’s relatively high rate of production of goods and services, the country still does not manage-to feed itself. In 1974, Mexico bought large amounts of wheat and corn from the United States. Almost all the heavy machinery for industry comes from outside Mexico, although officials hope that oil revenue will help counter Mexico’s dependence on outsiders.

Mexico’s rate of inflation last year was about twenty-five per cent. The government imposed price controls on clothing, food, cars, most raw materials, metals, and a wide range of products, in attempts to control inflation. Another counter measure, and one conceived to bring additional funds to the government, was a luxury tax on gasoline, cars, liquor, and tobacco, and a large income tax on families in the higher income brackets. Labor has been another factor in rising inflation. Mexico has a low wage scale in all areas as a matter of tradition, but labor has bargained for — and obtained — two significant wage rises in a year. Workers occupy a strong position in Mexico’s economy, and the unions are powerful even within the nationalized oil industry.

“Oil workmen have been and are now the most important resource of Petroleos Mexicanos,” the director general said at Reforma. “First as manpower…then as a basic element of the independent development of the industry, and now as a decisive factor in productivity.”

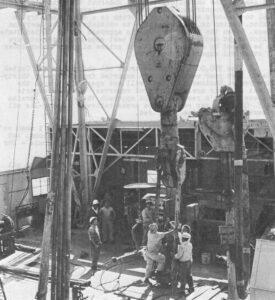

| Mexican roughneck on a well in Tabasco |

Any visitor to Mexico today will be struck by the prosperity of the middle class. For the last thirty years, Mexico has had one of the highest growth rates of any developing country, but most of the proceeds have gone to a relatively small number of Mexicans. Five per cent of all Mexicans receive almost forty per cent of the nation’s income. The bottom half of the population receives only sixteen per cent of the income, and almost three-quarters of the population earns less than $100 a month.

President Echeverria has attempted a number of social and political reforms, to re-distribute some of the wealth without damaging the system. He has tried to increase tax collections, control prices, build roads and schools, increase wages, and institute family planning programs. At the time when the labor unions and powerful industrial leaders were negotiating the general wage increase, Echeverria announced, “The government is fulfilling its moral and constitutional promise to fight at the side of the workers.”

Mexican leaders may describe their government as revolutionary and socialist, but industrial and commercial growth has enriched a small minority, and has been made possible with the help of American investment. There is a monument in Chapultepec Park commemorating the seizure of the American oil wells in 1938, but Mexico has been careful to preserve its good relationship with the United States.

This close relationship has led to criticism by the left in Mexico, and has sometimes proved embarrassing to both countries. The reaction of the United States to Mexico’s big oil discovery is the best example, for it indicated that we took Mexico for granted. American oil and interests, with government approval, planted stories in the American press alleging that Mexico’s oil bonanza would be a major factor in breaking up the international oil cartel. This angered PEMEX officials, and Mexico’s politicians, because it indicated that Mexico was subservient to the United States, and to its interests.

“Mexico will never be the Trojan horse of the multinational corporations,” said the Secretary of National Patrimony, Horacio Flores de la Pena. When Echeverria met with President Ford at the United States-Mexican border last October, Echeverria told the President “Mexico would sell its oil to whoever wants to buy it at current world prices on the world market.” And the United States very much wanted to buy Mexican oil.

It is quite possible that Mexico will in fact follow the lead of the United States, and undercut the prices set by the OPEC countries. American business investment is crucial to Mexico’s economy, and tourism is a major industry in Mexico. Mexico is very sensitive to criticism in the American press. Given the proper diplomatic approach by the United States, Mexico might decide that its own best economic interests are to be served by selling its oil at prices slightly under those of other oil exporting countries.

The 350,000 barrels of crude oil shipped to the United States last year were the first exported from Mexico in thirty-five years. Mexican officials will not speculate now on the extent of their newly discovered reserves, but some experts believe Mexico’s reserves could approach those of the Persian Gulf. Only ten per cent of the areas believed to over-lie oil reserves have yet been explored.

One official of PEMEX recently joked, “I don’t mean we’ll ever compete with the Arab countries with their billions, but we might be able to buy back part of Texas or California — for spot cash.”

Much more likely, Mexico will be able — thanks to oil — to enter into a more equitable relationship with the United States, and at the same time move more decisively toward distributing wealth, and social benefits.

| A drilling crew working near Reforma |

Next month’s letter will deal with alternate energy sources.

Received in New York on April 22, 1975

©1975 James Conaway

James Conaway, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Conaway and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.