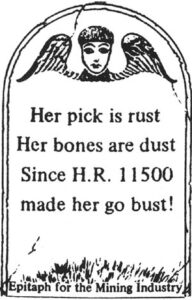

The bill regulating strip mining that vas recently passed by the House of Representatives is no deathblow to coal as loose industry representatives say it is. But, the bill did effectively dampen the notion of stripping Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota as a fast and highly profitable response to the present energy shortage, and it may well have altered the future of coal mining in America. H.R. 11500, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1974, the Interior Committee bill co-sponsored by Morris K. Udall of Arizona, and Patsy T. Mink of Hawaii, sparked one of the longest and most acrimonious debates in years, centering not just on land reclamation but an the issues of east versus west in future coal production, and on the social responsibility of an industry that has abused the lend for too long.

The bill, presently in conference, does set environmental standards for mine operators, and it requires that land be returned to its approximate original contour after stripping. It differs only slightly from an equally strict Senate bill passed last fall, and the House vote of 291 to 81 suggests that a Presidential veto would be overridden. The debate illustrated the relative strengths of the mining and environmentalist lobbies, and the mood of Congress that had delayed such legislation for years. The Udall bill was actually a between extremists on both sides.

The coal industry’s spokesman in Congress, Rep. Craig Hosmer, a Republican from southern California, proposed his own substitute bill that would have eased reclamation and permit requirements, and restrictions upon the type of land that could be mined. Hosmer claimed that H.R. 11500 was “absolutely unworkable, like trying to grow bananas on Pike’s Peak.” His stalling tactics – he repeatedly called for a quorum, alienating even some of his own party who might have voted with him – and a barrage of weakening were approved of by mining industry representatives, many of whom sat glowering in the gallery. Hosmer sent out daily “thoughts” to his colleagues in the form of expensively printed handbills, advising them that the Udall bill was “an extremist vehicle,” and referring to the opposing lobby as “the green bigot brigade.”

The coal industry’s spokesman in Congress, Rep. Craig Hosmer, a Republican from southern California, proposed his own substitute bill that would have eased reclamation and permit requirements, and restrictions upon the type of land that could be mined. Hosmer claimed that H.R. 11500 was “absolutely unworkable, like trying to grow bananas on Pike’s Peak.” His stalling tactics – he repeatedly called for a quorum, alienating even some of his own party who might have voted with him – and a barrage of weakening were approved of by mining industry representatives, many of whom sat glowering in the gallery. Hosmer sent out daily “thoughts” to his colleagues in the form of expensively printed handbills, advising them that the Udall bill was “an extremist vehicle,” and referring to the opposing lobby as “the green bigot brigade.”

Another substitute bill that would have abolished strip mining over a period of years was introduced by Rep. Ken Hechler, Democrat of West Virginia. During the debate, Hechler told the House, “The strip mining issue is one of the reasons why garbage collectors rate higher than Congressmen in recent public opinion poll…. The only my to tackle the curse of strip mining is to do like the garbage man – clean it up without pussyfooting around the edges.”

Defeat of the Hosmer and Hechler substitute bills was expected, but their supporters outside Congress felt both would strengthen support for their favored amendments to the Udall bill. Among Hosmer’s most ardent backers were the National Coal Association, the American Mining Congress, and the National Association of Electric Companies, which paid to bring to Washington people from the districts of wavering congressmen, to warn then of the political implications, of raised utility rates, or of constituents “freezing in the dark” because of too stringent regulation of strip mining.

Hechler was supported by saw 40 grassroots environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, the Environmental Policy Center, the National Wildlife Federation, the Wilderness Society, the National Audubon Society, the Friends of the Earth, Environmental Action, and Concern.

Congressmen admitted they had never seen such heavy and blatamt, lobbying. Wayne Aspinall, former chairman of the House Interior Committee, represented the Amax Coal Company, prompting charges that he was violating Rule 23 of the House, which prohibits former members of Congress from being an the floor during debate of an issue in which they have a specific interest. The Speaker’s lobby was lined during the six days of debate with mounted placards admonishing congressmen to vote for one or the other of the substitute bills.

The Hechler substitute bill received only 69 votes, but the decisive vote against the Hosmer substitute, 255-156, suggested that the final Udall bill would be strengthened rather than weakened. Those responsible for contributing to support for the strong amendments to the Udall bill were John Melcher, Democrat of Montana, Wayne Hays, Democrat of Ohio, Frank Evans, Democrat of Colorado, Teno Roncalio, Democrat of Wyoming, Mark Andrews, Republican of North Dakota, and John Heins, Republican of Pennsylvania.

The reclamation issue, which two years ago was central to the debate had become secondary. “We have to be good stewards of our Creator’s bounty,” intoned J. Allen Overton, president of the American Mining Congress, in an interview. “We have to liberate the minerals, and then restore the land. Let it be reclaimed, but don’t say how we have to do it.”

The environmentalists, on the other hands, claimed that the restoration of mined land – returning it to productive, sightly use – had become a red herring.

“The real issue,” says Pat Sweeney, one of the organizers of Montana’s North Plains Resources Councils, who cow to Washington to work with the Environmental Policy Center, “is where the money is to be concentrated. Will it flow through the regions where the coal is, or through the big corporations. If several billion dollars are to be spent during, the next few years, energy sources should be found in all rooms of the United States. But the federal government’s policy is to find an energy source, and exploit that. The government enjoys the promotional aspect of development – they want to be able to say where the power plants will be located, how much land will be leased for coal mining, how much water will be used. They think of land reclamation an only the janitorial side.”

Several groups supporting Hechler claimed before the debate that H.R. 11500 would simply legitimize strip mining. But after passage of the bill, the environmentalists claimed a victory. The bill that emerges from conference will almost certainly outlaw “highwalls” – debris left by power shovels and bulldozers along the rims of strip mines (20,000 miles of highwall exist in Appalachia today) – and back-filling and re-grading will be required, with segregated topsoil returned to the surface. The practice of shoveling “over-burden” – debris produced by strip mining – down mountain slopes will also probably be outlawed, a practice that, has reduced many rivers In the eastern United States to mild sulfuric acid.

The real points of contention over H.R. 11500 were those provisions eat would limit, large-scale stripping of western states, when the impetus of the industry lay in that direction. Vast deposits of low sulphur coal lie in eastern Montana, northern Wyoming, and western North Dakota, in thick seams that often lie only a few feet below the surface. This coal is cheap and easy to mine. It takes approximately half the time to develop a strip mine as it does a deep coal mine; deep mining techniques and federal safety regulations add greatly to the cost. A move vest by the industry would mean big, quick profits, much of it from land that has already been leased by the federal government. But a shift went would mean that deep mining technology would be neglected, that much capital investment would leave the east.

The argument for western expansion was that the low sulphur coal there meets the of the Clean Air Act, whereas some 90 per cent of eastern coal does not. The uncertain results of stack gas scrubber technology have given the utilities a seemingly strong argument for a move moist. In its annual report last year, the American Electric Power Company, the nation’s largest electric utility, asked, “Till we be permitted to bum our coal?” Plans for shipping western coal as far east as West Virginia have been seriously considered.

The environmentalists claim that enough low sulphur coal exists in the east; it is just costlier to mine. Importing coal from the most is expensive, and perhaps no more economical than adding the required cleaning devices to existing power plants. The production of power by plants built close to the source of western coal in another possibility, but the cost of transmitting power long distances is also great. Western coal in lower in Btu value, and therefore more of it has to be burned to produce as much heat as a given quantity of eastern coal. Another reason for utilities to look west is that large tracts of coal reserves are easy to assemble, because ownership in loss fragmented than in the east. Millions of tons of coal might be bought from one owner in the west – often this owner had been the federal government – whereas in the east an equal amount of coal would have to come from many owners.

The productivity of strip mines is more then three times that of deep mines. Most western strip mining operations that employ union members are organized by the International Union of Operating Engineers (AFL-CIO). Less than 10 per cent of the membership of the more rigorous United Mine Workers lies vast of the Mississippi.

The coal companies – the biggest of which are all owned by the major oil companies – insist that the greatest demand for coal win come between 1975 and 1980, and that the massive seams of accessible coal in the went offer the best opportunity for meeting that demand. Smaller companies in the east would not be able to afford the move west, and the big companies would simply get bigger. The strip mining issue in closely tied to federal air quality standards, and to land use planning, and it is the limitations here that the industry uses to justify the shift west.

Carl Bagge, president of the Rational Coal Association, explains why the utilities want western coal: “Utilities don’t have any alternative an long an we have this brinkmanship, approach to the Clean Air Act – constantly juggling compliance dates without assuring the industry they’ll be able to burn non-complying coal so long as sulphur removal technology is not perfected.”

Bagge claims that H.R. 11500 will halt industrial production in many areas of the United States.

Publicly, the Nixon administration refused to take sides on the east-west Issue. But the Interior Department has for years been supporting western expansion through coal research priorities, and the leasing of government land. Interior Secretary Rogers C.B. Morton opposed the amendments that would have limited western expansion, and research and development for coal gasification and liquefaction that rely heavily on the mining of western coal. Resumption of federal leasing depends upon the adoption into law of the Mansfield amendment to the Senate strip-mining bill.

This amendment prohibits strip mining, but allows deep mini of federally owned coal reserves where the surface owner is anyone other than the federal government. Supporters of the feel that it follows the intent of the Homestead Acts passed at the turn of the century that reserved mineral rights for the federal government at a time when only deep mining was perceived an a method of extracting coal.

Sen. Mike Mansfield said in an interview, “I don’t want Montana, to become an energy reservoir for the Midwest, east, or northwest… I don’t want to see us bilked out of our energy resources of coal in a haphazard indiscriminate manner.”

The east-west issue produced an odd coalition of liberal Western Democrats, such as Mansfield, conservative Western Republicans, such as Sen. Pete V. Domenici of New Mexico, and eastern senators congressmen of all persuasions, apprehensive of wide scale unemployment in the east if the coal mining industry moved out. The westerners feared rapid, uncontrolled growth, followed by massive unemployment when the coal is gone, and a ravaged countyside unsuitable for the ranching and farming it supported before.

The Mansfield amendment affects only western land originally granted under the Homestead Acts. Since the land is arranged in a checkerboard pattern, the amendment would protect that pattern, and prevent massive shifts of land from agriculture to mining. In the past, coal companies have used the threat of condemnation of surface land to convince ranchers to sell their rights. The Mansfield amendment, if adopted, will limit the scale and extent of the shift in ownership, but will not prevent strip mining in the west.

The House bill included rights for surface owner protection through written consent. Other curbs on western strip mining in H.R. 11500 were prohibitions on mining alluvial valley floors in semi-arid areas, and mining in the national Grasslands.

Rep. Frank Evans offered the protecting the alluvial valley floors, where sand and gravel deposits often contain underground aquifers so important in the west where rainfall in often no mare than 14 inches annually. These valley floors produce the hay that feeds the cattle, and disruption of the process could cause long-lasting damage in an area where a delicate balance between productivity and su.1mistence has been maintained for more than a century.

The national Grasslands amendment was offered by John Dingell, Democrat of Michigan, and seem to follow the intent of the Bankhead Jones Act of 1937, amended in 1962 to provide some development, “but not to build industrial parks or establish private, industrial or commercial enterprises” on the national Grasslands. Such a law would affect companies such as Arco, which claim to hold leases an over 5,000 acres In the Thunder Basin National Grasslands.

Under the now law, strip miners will almost certainly be made to demonstrate that mined land can be reclaimed – something that has never been demonstrated conclusively in Montana and neighboring states. Mine operators would be required to post a bond – the cost of a third party reclaiming the land and the bond might be held for a decade. Coal miners claim that bonded indebtedness in yet another prohibition to stripping in the west.

Federal regulation of strip mining will not preclude mining in the west, but it will prevent the bonanza foreseen by Interior and the industry. Rep. John Melcher, a key figure in the passage of H.R. 11500, opposes the prohibition on the mining of federal coal where the government does not also own the land. Melcher favors consent of the landowners involved, a provision the environmentalists and some ranchers feel would open the door to further land speculation.

Melcher’s home is in Forsyth, a town in eastern Montana due to receive many of the immediate benefits of expanded coal production in the area, already being mined by Montana Power and Peabody Coal Company. Forsyth is also due to receive some of the less desirable effects of production: pollution from steam generator plants now under construction at near-by Colstrip, an influx of people that could greatly alter the way of life. Melcher foresees “some” coal gasification, and coal production on a much more orderly basis than was originally proclaimed. He would like to see the creation of a reclamation fund to remain in the area where it in collected, to help pay for the impact of coal production on roads, schools, and hospitals.

The Udall bill contains a unique provision for the enforcement of reclamation standards. Funds will be provided by the federal government, but the states will be given the job of policing mine operators. Only if the states fail to enforce the land reclamation standards win the government step in. This provision has wide implications for other industries, and is likely to be cited in future bills regarding federal regulation of all kinds.

In the strip mining debate lurked the general issue of the right of any industry, in conjunction with a department of the federal government, to radically alter economic and social conditions in a large area of the country. This precipitated an elemental that largely vent unreported, and at times transcended the practical aspects of the argument. At one point an administrative aide who helped draft H.R. 11500 told a representative of the mining industry in private, “You’ve missed the whole point. We’re not interested so much in land reclamation. We want to write a new social contract for mining.”

The mining representative reacted heatedly, and with conviction: “I know Rousseau’s argument. And I also know Karl Marx’s.”

One aspect of the debate that tends to become obscured in the flood of statistics, accusations, and rhetoric, is the right of the individual. There remain in the west thousands of acres of land and coal owned by ranchers, Indians, and railroads, and much of the future of strip mining in the North Plains depends upon their decision.

Received in New York August 21, 1974

©1974 James Conaway

James Conaway, a freelance writer, In an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Conaway and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.