Every Sunday morning Bud Redding and his wife climb into their pick-up after breakfast, and begin a long drive that will not bring them home again until after sundown. They may visit say of a number of towns in eastern Montana – Roundup, Forsyth, or Billings – not because they particularly enjoy traveling, or because they want to leave home on the one day a farmer and rancher can relax and loaf a little. The Reddings leave home every Sunday because the opening of the strip mine on the edge of their property by Westmoreland Resources brings the curious from miles around. Most of them are acquainted with the Reddings, and either feel obliged to visit, or compelled to discuss the progress of the huge dragline, and its effects on the Reddings. Sometimes they just ask directions, before driving up the fence line to gape at the cavernous hole lined with thick seams of black, sub-bituminous coal, and the towering boom of the dragline, that dwarfs the hills seem from the read. It in capable of moving seventy-five tons of rock in a single scoop, one scoop a minute – sore them 70,000 tons of “over-burden” in a single two-shift working day.

Bud Redding grew up in Sarpy Creek, after his father moved the fanny up from Indian, territory in northern sixty years ago. Most of the Reddings’ waking hours have been devoted to improving the old homestead, buying up extra property when the Depression and attendant drought drove out other, lose hardy sodbusters. The senior Reddings still live in the original log cabin, where they raised their own son, John, teaching him a rare combination of cattle and farming lore that has enabled all the Reddings – three generations now – to earn an adequate living on their place, and to enjoy some of the most uncluttered land and cleanest air in America.

Bud Redding grew up in Sarpy Creek, after his father moved the fanny up from Indian, territory in northern sixty years ago. Most of the Reddings’ waking hours have been devoted to improving the old homestead, buying up extra property when the Depression and attendant drought drove out other, lose hardy sodbusters. The senior Reddings still live in the original log cabin, where they raised their own son, John, teaching him a rare combination of cattle and farming lore that has enabled all the Reddings – three generations now – to earn an adequate living on their place, and to enjoy some of the most uncluttered land and cleanest air in America.

John Redding had his own house built down the road from his parents’, and today in largely responsible for raising the Redding cattle, and sowing the wheat. Although the land is arid – less than fifteen inches of rainfall annually – and the topsoil often no sore than a few inches thick, the Reddings are able to produce an much an fifty bushels of wheat an acre, without fertilization, simply by rotating the land between crops of grass and grain.

John often stays at home on Sundays, just to keep an eye on the place, now that strip mining has brought so much traffic to Sarpy Crook. He drives slowly over the dirt roads and fields in his International Harvester truck – his wife drives the Ford pick-up – and he never leaves home without his binoculars, and his nickel-plated .22 caliber revolver, which rides high on the dash where it is easily visible.

“The gun’s all shot out,” John Redding says dismissively. “It’s only good for killing snakes. And impressing strangers.”

Redding is broad and solid, even by Montana standards, accustomed to long hours in the seat of a tractor. He in not accustomed to people trespassing either on his land, or his sensibilities. He once fired a bullet between the feet of a stubborn surveyor for a coal company, who told Redding he bad the right to walk all over his land, 1 but then changed his mind. Redding and another friend brought down a helicopter that had been hired by land speculators to enable them to place markers in the hills to which they had been denied access by landowners. Redding showed the pilot over-head his rifle, motioned for his to land, and the pilot complied.

“But by the time the story got back to me,” Redding says, “that helicopter had fifty bullet holes in it.”

John and Bud Redding have become local symbols of endurance, or hard-headedness, depending upon the point of view. They have effectively resisted efforts by various coal companies and land speculators – including threats of condemnation – to obtain a portion of the much for stripping. The Reddings own the surface rights to their land, but the rights to the minerals under the land belong either to the federal government, or to the Crow Indiana on the neighboring reservation.

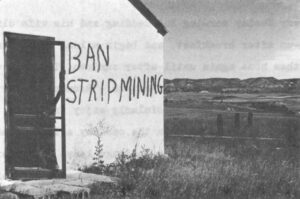

The methods of Westmoreland and other coal companies – misrepresentation of ranchers’ demands and outright harassment included – are by now ancient history in Sarpy Creek. The now concern for the Reddings is whether or not to finally sell out, after a battle of years, for the highest price ever offered in eastern Montana for surface leases. Such a move would not only be an admission of defeat, it would also dishearten other ranchero and landowners opposed to strip mini who believe that massive stripping can be prevented in the West.

“Things won’t change for us, no matter what kind of strip mining law is passed by Congress,” says John Redding, in reference to the House, and Senate bills still in conference, and specifically to the Mansfield that would prevent the mini of federal coal under privately owned land.

Westmoreland is already skirting the Reddings’ barbed wire fence with their mine. Two now draglines have been ordered for Sarpy Creek, these capable of moving ninety tons in a single scoop. The blasting of the over-burden – the minor’s term for everything that lies between him and the coal – has thrown showers of rock into the Reddings’ fields. The dynamiting jars the countryside at regular intervals throughout the day and night, and adds to the general uneasiness of people who live within a few miles of the new mine.

Westmoreland has suffered from the ill will created. Metal gates installed on roads leading into the mine were regularly stolen, until they were replaced with coils of barbed wire. Shortly after the dragline was completed, someone slipped into the compound at night, gained entrance to the dragline operating compartment by climbing down a huge cable, and dealt the instrument panel several thousand dollars worth of damage.

Now guards are posted at the gate loading into the mine, and on the dragline itself. They sit like tiny insects beneath the boom’s thrust, watching the sightseers and farmers stirring up dust on the road along the Reddings’ fence. The visitors stand in the beds of their pick-ups, hands on hips, squinting at the mountains of shale that have transformed the landscape beyond what they imagined possible.

Much of the coal being scooped out of Sarpy Creek belongs to Westmoreland’s other neighbors, the Crow Indians. The Crows want to renegotiate leases that they believe were sold too cheaply, and they sought advice at a meeting of the National Congress of American Indians hold in Billings in late August. Representatives of many of the ninety member tribes urged adoption of the Senate version of surface mining legislation, rather than the House version that would require consent of the surface owner before coal could be mined. Ninety per cost of the Crows’ coal lies under land owned by others.

The agreed upon royalty for Crow coal was 17 1/2 cents on every ton of coal mined, a figure they consider too low. They would like to develop their own coal, but can’t raise sufficient capital, or develop markets.

A visiting Navajo told the meeting that his tribe welcomed the coal companies years ago, but later regretted the burden mining placed on local schools, health care, grazing, roads, and the problems of drugs and alcoholism.

“’Somebody has to look out for the people, and prepare then for what will come,” he warned. “If the people aren’t prepared, they will face tragic problems. It’s fine to lease coal, but you have to realize that you have people to contend with, too. Your own people.”

The Indians’ resentment of Westmoreland adds another element of uneasiness to Sarpy Creek. In the nearby town of Hardin, members of the American Indian Movement gathered earlier this year, and it was rumored that they intended to occupy the dragline at Westmoreland’s mine to dramatize their demands, an action similar to that at Wounded Knee. The sheriff of Hardin closed all the bars, and began to deputize son for miles around to use against the possible up rising. One of the men the sheriff telephoned for help was John Redding.

“It’s a good thing I wasn’t hone when he called,” says Redding. “I could have told his a few things he wouldn’t want to boar about that mine.”

He points out that strip mining in Sarpy Creek has already taken many acres out of production that could have been supporting wheat or cattle.

“And by destroying the coal seams, they’re also destroying the natural course of water that travels for miles underground. Every time Westmoreland starts dynamiting, the water in our wells turns muddy. Once the underground waterways are destroyed, there’s no way to replace them.”

Coal-fired generators just over the Wolf Mountains are another concern. Evidence of the production of electricity beyond the mountains lies in the transmission lines strung between high metal stanchions that stalk across the Reddings’ land. The lines are fed by Montana Power Company’s now plant in Colstrip, fed by Western Energy coal stripped at the plant location. The Reddings sold the right of way to Montana Power for the original lines, and were later told that more lines would be built to accommodate the increased power production.

“We raised hell with then over those now limes,” John Redding says, with some satisfaction. “And it worked. You look at a map of their new development, and you can see those new transmission lines jog right around our property.”

He admits this in small satisfaction. Both he and his father feel that their land has already been transformed, even if it is not mined.

“We’ve been on this land for a long time. I like the idea of being able to b it over – intact – to my son when he’s old enough. Now I’m not sure the land will be worth anything.”

For the first time in the Reddings’ long fight with Westmoreland, they are considering selling their land. And ranchers and farmers all over eastern Montana are watching and waiting.

“I don’t know what will happen,” says Redding, with foreboding. “I feel like we’ve already lost.”

Sarpy Creek lies at the center of a proposed industrial complex that would supply electricity and liquid gas to other parts of the state, and to the Went Coast. According to a study by the National Academy of Sciences, the water supply in Montana is already “completely committed, perhaps over committed…. There is simply not enough water in Western states to permit the enormous congregations of coal-fired generating, gasification, and liquefaction plants envisioned in recent years by utilities and oil companion…. Any large scale commitment of water to on-the-spot consumption of coal would look such states an Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas into a coal based economy they hadn’t bargained for.”

Next month I will examine the effects of the coal-mining boom on the little settlement of Colstrip.

End Notes

1. The Homestead Act of 1914 retained rights to coal for the government.

Received in New York September 27, 1974

©1974 James Conaway

James Conaway, a freelance writer, in as Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Conaway and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.