“While our taxes have gone up, the quality of schooling that our kids are getting has gone down. Law enforcement has gone down. And the roads have gone plum to hell.”

That is a rancher’s evaluation of the effect of renewed strip mining, and the construction of an electrical generating complex at Colstrip, in eastern Montana. A resident of near-by Forsyth, the seat of Rosebud County, feels the effects of coal development in a different way:

That is a rancher’s evaluation of the effect of renewed strip mining, and the construction of an electrical generating complex at Colstrip, in eastern Montana. A resident of near-by Forsyth, the seat of Rosebud County, feels the effects of coal development in a different way:

“It’s really changing the social structure. I used to stop down and have a beer after work, but the bum are so rough now, I don’t. I’ve lived in Forsyth all my life, and it’s like it’s not my community anymore.”

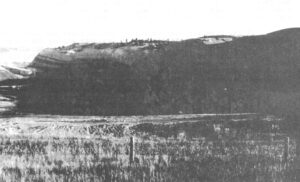

Rosebud County sits on top of one of the largest known deposits of low-sulphur coal, and the largest source of easily strippable coal in America. The little town of Colstrip has known boom times before, the name a tribute both to coal and to the method of extracting it that so changed the adjacent landscape. Some of the earliest strip mining anywhere was conducted here half a century ago, where a company settlement grow up on the and plain, and spoil banks soon came to over-shadow the natural sandstone formations that glow pink in the afternoon sun, and the sparse, rolling rangeland.

Today a subsidiary of the Montana Power Company, Western Energy, is once again engaged in full-scale stripping. Montana Power is constructing two coal-fired generating plants capable of producing 350 megawatts each, and proposes to build two-acre units after the present construction is completed. The new plants would be capable of producing 700 megawatts each, or a total of 2,100 megawatts for the entire complex. This is the equivalent of power produced by the infamous Four Corners generating complex in New Mexico, one of the world’s largest stationary sources of pollution.

Such a complex would require approximately 40,000 acre-feet of water per year (an acre foot of water is the amount required to cover an acre of land at a depth of one foot). This water would be taken from the Yellowstone River, the source of irrigation for the Yellowstone Basin. The Basin now uses more than three million acre feet a year to irrigate 600,000 acres of land, and needs even more water for land suitable for irrigation, if the water was available.

Montana Power claims that its complex at Colstrip will use a relatively small percentage of water available from the Yellowstone. Officials argue that the water should be put to use in Montana, rather than be “lost” to downstream states. Yet even now there isn’t enough water available for irrigation. Montana Power’s total appropriation at Forsyth is 180,000 acre feet – or approximately one-third of the flow of the Yellowstone’s lowest known level. This fact has many ranchers in the area worried about the availability of their own meager appropriations, once the complex is in full swing.

When I first visited Colstrip two years ago, the area retained the beauty and ingenuousness of an isolated agricultural community. Now the skyline is dominated by the first of Montana Power’s massive smoke stacks, and the second stack in half completed. Colstrip’s old spoil banks are no longer the most jarring irregularity in the sweeping, open country. The air is full of the dust of heavy trucks transporting supplies, and the amplified voice of the general foreman of the construction project that, literally carries for miles.

Big scapers scurry over the wide, black coal seams. Bulldozers grade new building sites and roads. Identical houses with prefabricated siding sit in rove like matchboxes, while hundreds of trailers line the open, graded flats stretching north and vest of the towering smoke stack. Montana Power is building its own company supermarket and surrounding shopping center, which will be highly profitable enterprises in themselves.

Development in Colstrip is so chaotic that no zoning board could possibly have foreseen all the complications that have arisen concerning schools, roads, hospital facilities, and taxes. But some problems could have been avoided, and some predictions made about the impact of coal development on a large scale were patently false.

According to Montana Power’s own prediction, Colstrip schools will have to accommodate more than 1,000 students during the 1974-1975 school year. That is an increase of about 500 per cent over the previous two years, since coal development was renewed. Last year, classes were held in every available space, including shower rooms. Courses such as physics and foreign languages had to be dropped, and classes were continually split up to handle ever-increasing enrollment. One student had a total of eight different teachers, and was moved from room to room, building to building. One of the best school systems in Montana declined dramatically.

During the lost two years, the taxes of ranchers in the Colstrip area have increased 42 per cent.

Coal industry spokesmen arguing for development in eastern Montana claimed that the boom would solve local tax problems. But in 1973 the increased valuation of cattle in Rosebud County exceeded the increased taxable valuation of coal development. The power complex projects presently constitute the largest industrial development in Montana, to exceed $180 million. Yet the complex has contributed only $1.6 million to county taxes. The taxable valuation in Rosebud County increased from approximately $20 million in 1973 to $26.5 million this year, with Colstrip’s development bearing only 26 per cent of that increase.

Another argument advanced by the coal industry was that development would provide jobs for everyone. Although employment has picked up in Rosebud County, most of the construction jobs at Colstrip have gone to outsiders, many of then from outside the state and this part of the West, who have little interest in the community itself.

The condition of roads in the Colstrip area provides another index of the effects of coal development. State highway 315, which carries traffic between Colstrip and the Interstate 94, thirty miles north at Forsyth, carried an average load of fifty cars, trucks or tractors a day an recently as five years ago. A year ago, the same highway carried more than one thousand vehicles a day, and the total reached two thousand vehicles one day this owner.

The law enforcement budget for the Colstrip area has quadrupled in the last two years.

Inadequate sewage facilities serve the company’s trailer parks. Available land along the highway that is not owned by ranchers has been leveled to accommodate more trailers.

“Not only are the older residents forced to accept a deterioration of roads, schools, law enforcement, recreational facilities, environment, and life style,” says Bill Gillin, who has lived near Colstrip, for years, “but they are also subjected to unbearable tax loads to provide social services for the employees of coal developers.”

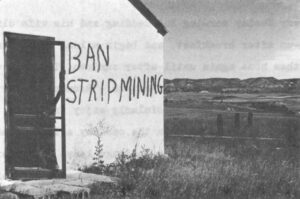

Reclamation, once the chief argument against coal development in this area, has been taken for granted by many state officials. Reclamation in this case means restoring the land to its approximate original contour, in a condition that will be able to sustain the same type and amount of plant cover that existed before strip mining occurred. Montana law requires mined land to be returned to productivity, and many assume that the existence of the law is sufficient protection against a sterile environment. But unfortunately, effective reclamation in an area with an average yearly rainfall of about fifteen inches remains unproven. Many ranchers doubt that any but the choicest acres bordering rivers and streams can be reclaimed.

| A ranch south of Colstrip, Montana |

Land at Colstrip is presently undergoing intensive cultivation by Western Energy, which is attempting to produce a showpiece to ease ranchers’ fears of a desolate moonscape to be left after the coal has been mined, and industry has moved away. This land appears to be more productive after three years than after five years. Most of the grass growing on the spoils was introduced, not self-starting, with heavy applications of fertilizer – about five hundred pounds per acre per year.

“That’s enough fertilizer to grow grass in the back of my pick-up,” says one rancher. The lament is a familiar one, and as old as reclamation efforts in the West.

The Montana State Agricultural Experimental Station has been conducting research at Colstrip since 1968. Its oldest cultivated plot has become the source of some concern. The introduced vegetation has deteriorated, in spite of the massive doses of fertilizer, and some species of grass have been lost. Weeds seem to be taking over. If it proves impossible to re-establish the native grasses of eastern Montana, then a useful agricultural resource will clearly have been diminished. Both cool and warm season grasses have survived the harsh climate and thin topsoil, providing valuable grazing, and their lose would seriously and permanently undermine the economic and social structure.

Ranchers and farmers for many miles around also fear the effects of air pollution on crops, grass, and cattle.

An even greater fear is that the construction of the additional power plants at Colstrip will set a precedent for other such complexes in eastern Montana. New power plants have already been proposed to provide electricity for the Pacific Northwest, and the Midwest. A million acres of federal coal in the West have been leaned by the Interior Department, one third of this coal in eastern Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota. Power companies other than Montana Power include the Puget Sound Power and Light Company, Portland General Electric Company, Washington Water Power Company, and the Pacific Power and Light Company. The joint effort to develop power in the area is called Colstrip Project Management, or CPM.

Transmission lines are another worry to local ranchers. Construction of the lines will require another influx of work crews and heavy machinery. Servicing the lines constitutes a major disruption of agricultural activities, some ranchers claim.

Saline seep is another problem of reclamation. Rainwater is absorbed by the mining spoils, dissolving the salts in the “over-burden.” High evaporation rates pull the salts and sodium back to the surface, where they hamper plant growth. Sodic water produced from the spoils can produce a saline bog near a minim site, because impermeable shale and clay layers carry the sodic water for some distance underground.

The ranchers are sensitive to charges that they selfishly guard their own interests, without due regard for the interests of the country as a whole. Many have made efforts to cut back on their own consumption of energy, and expect other Americans to do the same. Food, they argue, is more important than coal. Their area can produce cattle and grain indefinitely, while coal development would only last for two decades, and could rain the land forever.

“You’ve got to think of the people who will come along after us,” says a rancher living outside Forsyth. “We’ve got no right just to tear up the land for our own use. It belongs to everybody, including future generations.”

Coal developers and federal energy officials have relied heavily on the energy crisis to lend support to the notion that the coal should be mined quickly and massively. The country, they said, needs the coal – strip mining is for the general good. A representative of Westmoreland Resources, which mines coal not far from Colstrip, said to me in defense of his company’s policies, “Individuals have to give way to the general good. That’s what the free enterprise system is all about.”

It has recently come to light that Westmoreland conducted elaborate and secret negotiations with Japanese mining and shipping companies concerning its mine in eastern Montana. An agreement to export millions of tons of coal a year to Japan was abruptly cancelled by the Japanese when it became public knowledge that none 12,000 tons of “top ” coal were shipped to Japan from the Westmoreland mine in August.

Ranchers protested the test burn at a hearing of the Federal Energy Administration in Billings earlier this month. Bob Tully, chairman of the Northern Plains Resource Council — the grass-roots organization made up of ranchers and others opposed to strip mining in the West — summed up the general feeling of distrust.

“What more need be said to illustrate the complete lack of justification for a wide-open coal policy, supposedly to save the nation in its hour of energy need?”

Some ranchers do favor the, development of coal in eastern Montana. Most of them own a considerable amount of the coal under their own land, with the balance being owned either by the federal government, the Crow or Cheyenne Indiana, the state, or the Burlington Northern railroad.

Mark Nance, of Birney, south of Colstrip, owns sixteen million tons of coal under 320 acres, and he wants it mined because it means several million dollars that he can put back into his ranch. The land lies near enough to the river to allow heavy irrigation of the spoils. “I dream about this,” he said, with real enthusiasm. “I honestly think it can be done.”

Nance and other ranchers in favor of strip mining have a common fear of its consequences. They abhor the influx of people more than possible air and water pollution.

“Things are just going to be different,” said one. And he added, “I suppose you can got used to most anything. Even Colstrip.”

(Next we’ll pay a visit to the Coal and the Environment Conference in Louisville.)

Received in New York on October 30, 1974.

©1974 James Conaway

James Conaway, a freelance writer, is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Conaway and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.