Fairbanks, Alaska January 26, 1972

Alaskan Eskimos and Indians have just won the biggest land claims settlement in history – 40 million acres, $465 million in federal funds and $500 million in state mineral rights. Their holdings are to equal roughly two percent of all the land in the United States. If considered a single business entity, the Alaskan natives would qualify among the 10 largest corporations in the country.

Alaskan Eskimos and Indians have just won the biggest land claims settlement in history – 40 million acres, $465 million in federal funds and $500 million in state mineral rights. Their holdings are to equal roughly two percent of all the land in the United States. If considered a single business entity, the Alaskan natives would qualify among the 10 largest corporations in the country.

The stockholders, however, are traditionally impoverished people. Village family income averages less than one-quarter the family income of white Americans. Over 70 percent of the native population is dependent on subsistence hunting and fishing. And there’s still no cash on hand.

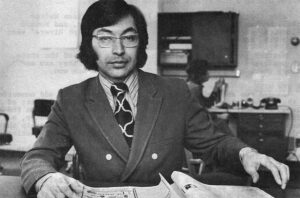

“I’ll tell you there’ll probably be no cash flow to anybody in the next two years,” Harry Carter, executive director of the Alaska Federation of Natives (AFN), explained over the telephone to an Eskimo stranded in Oregon. The call is typical of dozens his office receives each week. “I’ll try and see if anyone can help you … No, jobs are kind of scarce up here right now.”

“We’ve got lots of problems,” Carter admits. “But that’s nothing new. We understand deficit spending. We’re used to that. We’ve been doing it for five years.”

To finance the land claims suit, AFN borrowed $525,000 in direct loans from other Indian organizations and banks. This is covered in the claims settlement but that money won’t come in until completion of native enrollment, which is at least two years off.

Currently there is no funding available to explore incorporation of 13 regional organizations as required by Congress, or for much needed investment planning. Sen. Mike Gravel has suggested President Nixon’s contingency fund be tapped. Sen. Ted Stevens thinks the state might offer a loan. Government agencies like the Office of Economic Opportunity are being buttonholed and some regions are negotiating bank loans.

A Good Credit Risk

Despite empty pockets, the native credit rating has risen considerably since 1967 when their only collateral was aboriginal title and a fledgling coalition.

“Collectively, if we operate as a business we can’t fail,” Carter maintains. “Our resources in terms of Indian ownership are tremendous. Money talks!” Don Wright, AFN president, agrees.

“Many of our people don’t understand what the land claims settlement really is,” he said. “They don’t have the feeling of its economic impact on the whole state. They don’t have the feeling of their own political muscle.

“We’re on the threshold of a mass education era on exactly who they are now and that they have a land base and a money base and what strong clout they have. Give them five or six years and I think there won’t be a single native who doesn’t understand what it means to vote.

“The first thing after the people are informed they have true, equal standing, we have to educate the rest of the state to the same thing.”

The farsighted have already noticed. Even the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce, loudest spokesman for the white opposition, has reconsidered.

“Like good losers in the sandlot league, the Chamber of Commerce extended a conciliatory hand today to the Alaska Federation of Natives and invited the winners of the 87 year-old land claims hassle to draw on the talents of the business community, to work for the mutual benefit of all Alaska,” the Anchorage Times recently reported.

“‘Let’s give the natives the whole state. In three weeks we can take it away from them.’ That’s what they were saying in Anchorage,” recalls Donald Simasko, independent oil operator. “But they’re wrong. I’ve never seen a more competent lobby than the natives. I think the settlement was too high, but it’s done.”

Like most oil men, Simasko hopes the natives will prove easier to deal with in land leasing than the government.

“If they want to take the risk they might decide to form their own oil companies,” he speculated. “The wave of outside interest generated by Prudhoe Bay has fizzled to a froth on the beach. There have been so many delays, and now the governor is attempting to nationalize the pipeline. It’s frightening the oil industry away.”

“I think the settlement is one of the greatest things to happen, not only for the natives but for the state,” reasons A. F. Morel who heads the Native Affairs office of Alyeska Pipeline. “No one could do anything. No one knew who owned what. This is going to release land.”

Elmer Rasmuson, head of the National Bank of Alaska, stands by his land claims statement of 1968: The greatest undeveloped resource we have in Alaska today is our native population…

“The settlement needs to be generous, because we all know that it is the surplus over our subsistence that is saved and reinvested. Thus the native population becomes a strong contributory force to our economy which generates new business, broadens our tax base and creates additional investments.

“It can only be a plus factor,” he added recently. “By getting the land into private hands, there’s got to be advantages. The history of the natives is that they don’t just sit on land. They lease. They develop.”

But, he cautioned, the settlement will not touch off a boom. The state award is only a transfer of purchasing power. It will be 20 years before individual natives can sell their shares and the problem of developing rural areas will remain a tough one.

State Within a State

Another generally voiced concern is that settlement legislation establishes a socialistic state within a state, demanding too much skill from the natives as stockholders and citizens.

“In my judgement they can’t fail,” argues Don Wright. “It’s true capitalism because each individual is free to invest, but each is dependent on the other for development.”

AFN director Carter concedes the native people have not had the educational opportunities of the average citizen. Many do not speak English.

“But we’ve got lots of youngsters going to school now. Three hundred at University of Alaska, 125 at Alaska Methodist University. I guess in all we’ve got 500. That’s where the power is.”

“The ironic thing is that the bill calls for a 20 year period of inalienation (when stock cannot be sold),” Wright noted. “It gives every native enrolled a chance to become an adult. The more I look at that, the more I think it’s a good, fair shot.

Even without education, natives may show more business savvy than sceptics predict. Joe Smith, manager of the federally funded Community Economic Development Corp., is pleased with the native ventures his agency has sponsored.

“We have 30 enterprises and all are managed by natives. Ninety percent of these showed up in the black at the year’s end,” he reported. “We’re extremely proud of that. The small business failure rate nationally is 80 percent and with the added risks of operating in rural Alaska it should be 95 percent.

“The people in rural Alaska may lack technical expertise like business administrators and accountants, but they can buy these services.”

The thing that bothers Smith is that the natives may be forced to shell out their investment capital for projects traditionally financed by public funds. The legislation demands review of federal aid to natives within three years and termination could result.

“The current budget for federal health care of natives here runs between $23 million and $28 million,”Dr. Jules Cohen, chief of the Arctic Health Research Center at the University of Alaska, observed. “The settlement is not going to go far if it has to be used to cover that.”

Another problem to be faced is protection of subsistence hunting and fishing. This was not written into the claims bill but left to local government agencies.

Barry Jackson, AFN lawyer, believes the state has power to protect subsistence rights but that it is not required to do so under law.

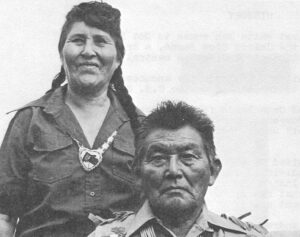

“We Inupiat Eskimos have never wanted money as such – we wanted land, because out of the land we could make our money,” protested Joe Upicksoun, president of the Arctic Slope Native Assn. (ASNA). “We would protect our subsistence living, and we would still have our heritage.

“This is a whiteman’s world. We are supposed to compete in that world. We are not against that. But how greedy can you be – that you start the race to western culture with so many tools – education, for example – and you want to gobble us up.”

ASNA lost more than any other natives by the settlement. It not only threatens their life style but takes away their claim to oil reserve land which might have helped finance their period of transition to a cash economy.

To recoup, the Inupiat have petitioned for borough status with power to tax the rich oil area. An independent auditing firm estimates it would take only a two mil tax to run the borough, leaving a sizable amount for the natives to reinvest.

There is heavy state opposition to this plan but Upicksoun and his people have researched well and Alaska’s constitution seems to be on the side of the Eskimos.

Survival of the Fittest

Now many observers predict a power struggle between the regions with survival of the fittest. Native leaders originally asked Congress to establish a statewide corporation but white opposition, fearing such a structure would wield too such power, successfully lobbied to break it into independent regions.

No provision was written into the bill for the Alaska Federation of Natives. The agency administers in excess of $3 million in grant programs plus a federal housing project that could run to $300 million, but the extent to which the regions will support it remains in doubt.

Recently the AFN board vetoed several of President Don Wright’s spending proposals including the purchase of a five seat plane, and appointed a 12 man regional task force to set new guidelines for the organization. Wright remains unperturbed and believes, with the majority of native leaders, that a coordinating agency will survive to form a strong regional union.

“After all, they said the Alaska Federation of Natives was impossible,” he recalls. “That the Indians, Aleuts and Eskimos could never work together. But our people just happened to be intelligent enough to recognize their opportunity and take advantage of it without individual self interest. Survival instinct, I guess you’d call it.”

Received in New York on January 31, 1972

©1972 Mrs. Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.