Fairbanks, Alaska August 9, 1972

A crowd of 1,500 watches silently. The air is hot and tacky, heavy with the strain of concentration. Reggie Joule, a young Alaskan Eskimo from Kotzebue, studies the high kick target which dangles almost two feet above his head. Twice he has failed to kick it in a style acceptable to the judges. If he fails again he is sure the Eskimo Olympic title will go to a Canadian.

Watching quietly nearby is Mickey Gordon, a 27-year-old athlete from the raw tundra of Inuvik on the MacKenzie River Delta. Back in Canada he holds the high kick record. He has jumped against Joule before and won. But something has happened to the Alaskan in the five months since the competed at the Canadian Winter Games. His style is better. He has knocked off some awkward edges.

Joule springs with bullet-like speed, feet above his head, sends the target flying and makes a balanced landing. The judges shake their heads. His two feet did not hit the floor at the same instant and Joule is disqualified.

No emotion registers on the Canadian’s face. He unwinds and with seeming ease he duplicates Joule’s jump, landing evenly on both feet. (See photo, Page 1). The mark was set at 6 ft. 11 1/2 in. but the Olympic record for the two-foot high kick is 7 ft. Gordon confers with the judges and they move the target to 7 ft. 1/2 in.

His first try goes sour; the second, too. But on his third and last attempt he recaptures his grace, sends the target skittering and lands with perfect timing on a new Olympic record. The crowd comes to life, shouting approval in Eskimo, Indian and English, and for the first time Gordon treats them to his handsome smile and sinks into the arms of his jubilant teammates.

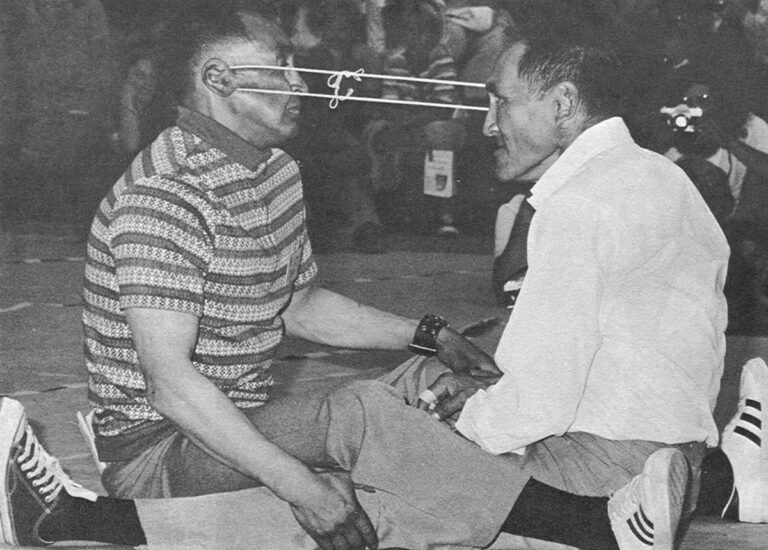

His rest is of short duration. The Inuvik men compete stubbornly in the tortuous ear pull contest but once again Gordon finds himself sole upholder of Canadian honor in the finals. He is matched against Joe Kaleak, 34, an unflinching Barrow Eskimo with all the expression of a stone.

They position, face to face, sitting stiff-legged on the gymnasium floor. Twice enroute to the finals Kaleak has broken the cotton string used in the pull. Now a double strand is looped from his left ear to Gordon’s right.

The judge signals. Both men tense and pull. Usually the event is scored in seconds but this, the final round, seems interminable. Pain overcomes Gordon’s stern control and shadows his face. Kaleak, unyielding, unrelenting, pulls steadily and the loop bites into Gordon’s flesh, cutting a bloody trail.

Gordon holds, keeps pulling until the loop in another instant will sever his ear. Then he slumps, bleeding profusely.

“I didn’t mean to do it. He just wouldn’t give up,” Kaleak says softly. It is the first time his eyes show any sign of pain.

“If you lose an ear you lose an ear,” reasons one of Gordon’s teammates. “In Inuvik we have a man who carried 20 pounds in an ear weight contest and went 22 laps. He didn’t want to give up either. We had to stop him or he’d have lost an ear.”

Gordon says nothing. A hundred years back a man would have preferred the loss of an ear over surrender. Today the path to honor is less clear.

Harsh as the Arctic

The Eskimo Olympic games are tests of pain, endurance and agility which have been handed down for centuries in Arctic villages. Some, like seal skinning and fish cutting contests, require practical skills for which competitors must have a good grasp of their native past. Others, like the ear pull, are as harsh as the Arctic environment that spawned them, demanding such high tolerance of pain they were once banned by missionaries because of their potential for crippling and maiming.

In the early 1960s, when missionaries and educators alike were pushing for acculturation, it appeared the native sports would be forgotten. This worried pioneering bush pilots of Wien Airways who’d seen the games in their hey-day and, in 1961, Wien organized the Eskimo Olympics.

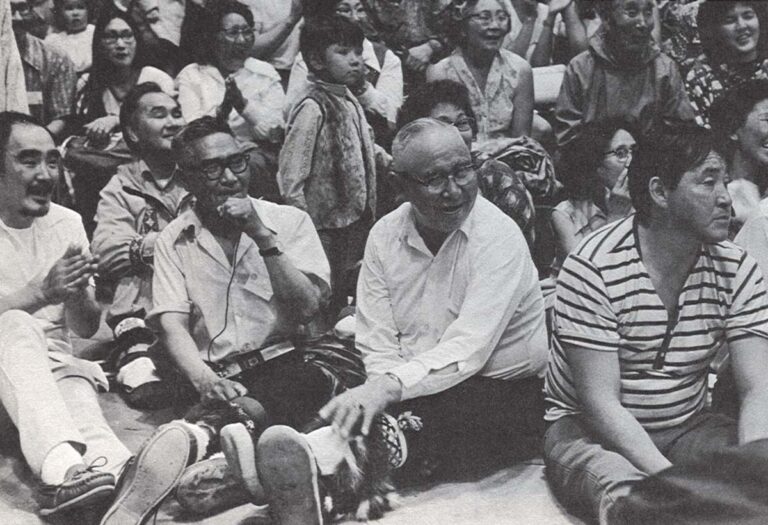

The first year only villagers from Barrow, Unalakleet, Tanana, Ft. Yukon and Noorvik participated, but enthusiasm ran high and a large crowd of spectators (tourists and residents of Fairbanks where the games were held) turned out to cheer them on. After that attendance snowballed and Indians began to appear enmasse to challenge the Eskimos who are traditionally their enemies.

In 1967 Canadian Eskimos from Inuvik attended, addIng a new dimension to the meet. Alaskan Eskimos – who had never met them but were related through obscure blood ties – were delighted to discover they shared much in common language, song and tradition. The mood of a good family reunion prevailed yet the Canadians brought with them a stiffer sense of competition than the Alaskans had known.

The Canadians have been groomed for the Arctic Winter Games staged every two years by their federal government. Their athletes train to compete; have a team, a coach and some expense money.

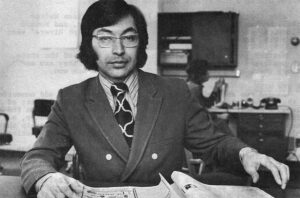

Alaskans, in contrast, have no organization at all. Sponsorship of the Olympics has drifted from the airlines to the Fairbanks Chamber of Commerce to (currently) the Tundra Times, a statewide Eskimo-Indian newspaper. There are no monetary prizes and participants are expected to pay their own transportation costs which can run over $300 from some remote areas of Alaska.

Board and room are furnished but the meet is staged in the very middle of Alaska’s short work season and often title defenders must choose between making an Olympic appearance or staying on a job (like fire fighting) which may be their only source of cash income for the year.

While the Canadians place high premium on training, practicing nightly a month before a major competition, Alaskan natives generally rely on natural ability and toughness gained battling their savage climate for a subsistence living.

“Training…that’s not our way,” maintains Gordon Killbear, one of Alaska’s fiercest contenders. “It’s just whoever is able to do it that’s it.”

Some Alaskan villages stage competitions during the Christmas season. Others hold them spasmodically. But there is no elimination process to send local champions to a state run-off, only individual initiative.

“One of the Alaskan competitors this season was so drunk the airline wouldn’t let him fly nine hours before he appeared in the games,” marvels an Olympics judge. “Yet he competed in one of the toughest events which he’d never tried before and came in third. Makes you wonder what would have happened if he’d been in training.”

In spite of Alaskans’ seeming casualness and haphazard appearance of contenders, they still take the Olympics seriously. Killbear, who shrugs off training as “not our way” is a good case in point.

Last year, competing for the first time, the 27-year-old Kotzebue man gave an outstanding performance in the knuckle hop. The game requires getting down on all fours and hopping on the knuckles in battering push-up fashion on a hardwood floor. Few men can stand the pain and the average distance covered by those who can is 20 feet.

Killbear gritted his teeth and hopped 61 feet breaking all records. For this year’s event he lost 20 pounds and covered a grinding 70 ft. 5 in. to beat his own record.

“It doesn’t pay to practice for that sport,” he grinned, brandishing a battered fist. Last year it took his hands two months to heal to the point where he could again compete.

But Killbear also won a new event called “Drop the Bomb,” which was introduced by the well-trained Inuvik delegation. The contest requires a man to stay absolutely rigid while four men carry him by his hands and feet. Muscle strain was so great that all contenders emerged trembling but Killbear held out a full lap beyond William Day, the Canadian runner-up.

About the only Alaskan to train seriously this year was Reggie Joule who attended the Canadian games with a small Alaskan delegation last winter.

Competing in the Olympics for his second season, he far outdistanced his past performance reaching 7 ft. 10 in. to win the one-foot high kick. The event was staged before the Canadians arrived (their plane was delayed) but there’s no question but what Joule could have given them a stiff fight as he did in the two-foot kick.

“I never knew I could do it but when I competed in the Winter Games, Inuvik coach, Ed Lennie, taught me the Canadian style of kicking,” he smiled. “I don’t think this is what he had in mind – my beating them – but it’s made a difference.”

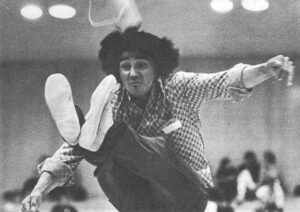

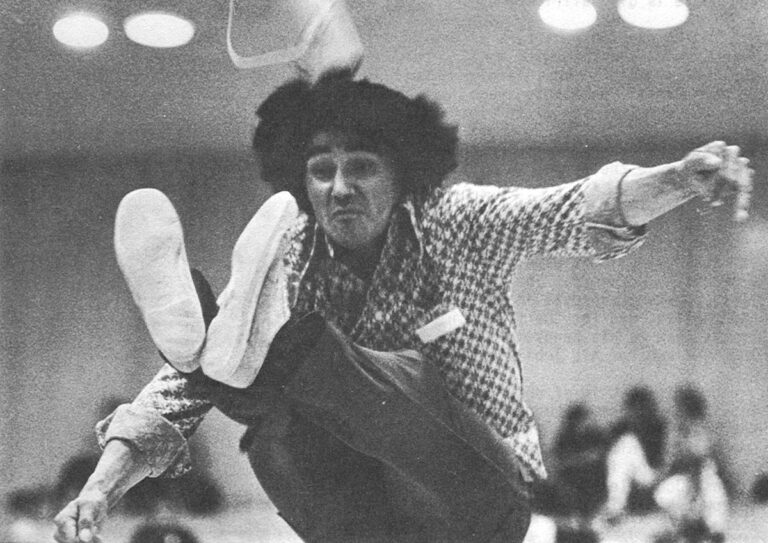

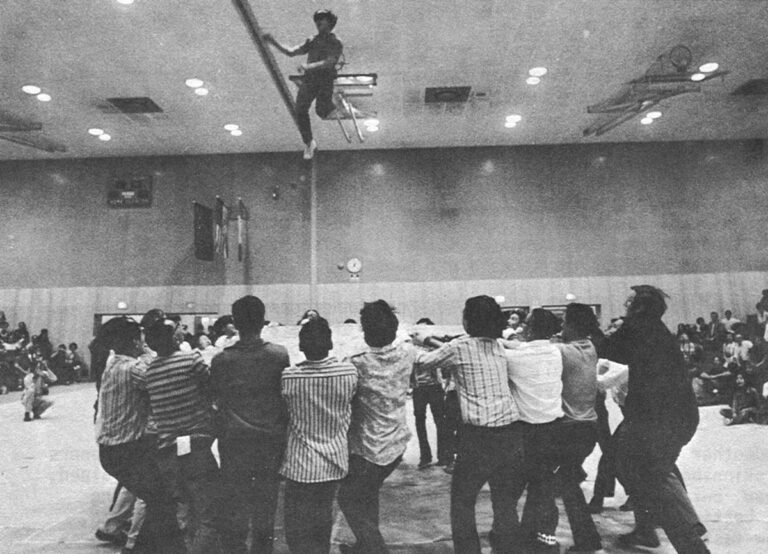

Joule also topped all comers in the men’s blanket toss, maneuvering with grace near the ceiling of the gymnasium on the toss of a walrus skin wielded by 20 sturdy men.

The blanket toss (Nalukatuk) originated in Eskimo whaling communities as part of the traditional celebration of the hunt. About the only chance most Eskimos get at it is during a whaling feast (staged once annually, at best) but Joule works as a guide for Alaska Airlines and practices often in the blanket toss the line sponsors as a tourist attraction. He also has a block hung behind his office so he can work on his kick in off hours.

Results of Joule’s practice have not gone unnoticed by other Alaskan athletes. The Bethel elementary school system now offers a gym course called “Eskimo Olympics” which will be taught this fall by Gordon Killbear and other Eskimo and Indian schools may follow suit. The essence of the Olympics, however, is preservation of the full native heritage, not simply perfection of a few athletic skills.

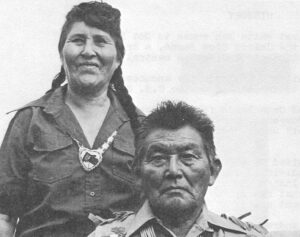

Grandmother Elizabeth Lampe of Barrow walked off with top Olympic honors in the seal skinning contest (1 min. 27 sec.) this season because she’d trained, not for a year, but a lifetime. Likewise Poldine Carlo won the fish cutting competition, beating out a younger, faster woman, because the judges decided, “It’s not how fast you do it but how good you do it.” After all, fish is for eating, not timing.

Elizabeth Lampe cleans her ulu after winning a seal skinning contest.

The fur parka design contest requires so much experience that only older women compete. Younger seamstresses content themselves sewing traditional costumes for the native baby contest but careful matching and stitching of furs are skills that take years to perfect.

The bulk of northern Olympic honors still go, not to professional athletes, but to Eskimos and Indians who follow the difficult dictates of their cultures.

In the Arctic it’s said that the older a man gets, the tougher he gets – careless to cold and pain because his body is hardened by the demands of this cruel land. The steely performance turned in by native contenders is impressive justification of this lifestyle and sometimes just watching can help bridge the generation gap for youngsters who still face major decisions on acculturation.

The “Now” Generation

Roy Harding Katairoak, 17, appears to be of the “now” generation. He’s at ease in Alaska’s major population centers, has hitched his way around Washington state and California. However, his mother’s people come from the isolated Eskimo country of Anaktuvuk Pass and Point Barrow and Katairoak has also tried to fit into their way of life.

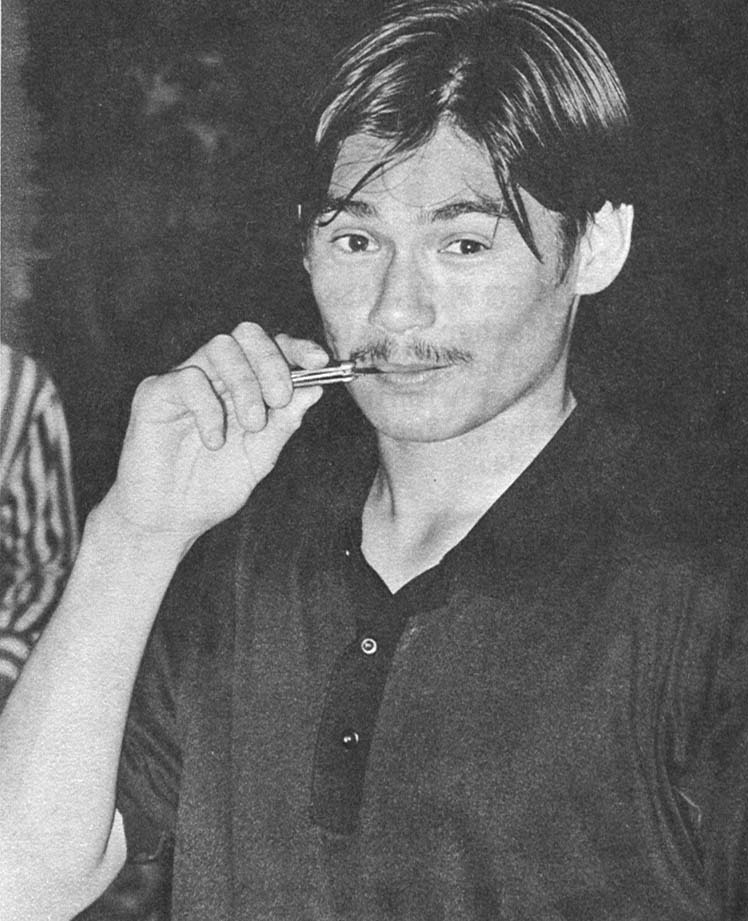

Roy Harding Katairoak – licks off his pocket knife after winning the muktuk eating championship.

It hasn’t been easy. He doesn’t speak Eskimo, although he understands it, and his northern cousins have been quick to make fun of this speech barrier and his city ways. It amuses them to see a boy his age – a man, actually – unschooled in the ways of the tundra and Katairoak sometimes finds it hard to cope.

Discouraged, he heads back to the city for a while. That’s where he was when this year’s Olympics came around and he decided to attend. He was at first a spectator but as the three day meet wore on, he itched to compete.

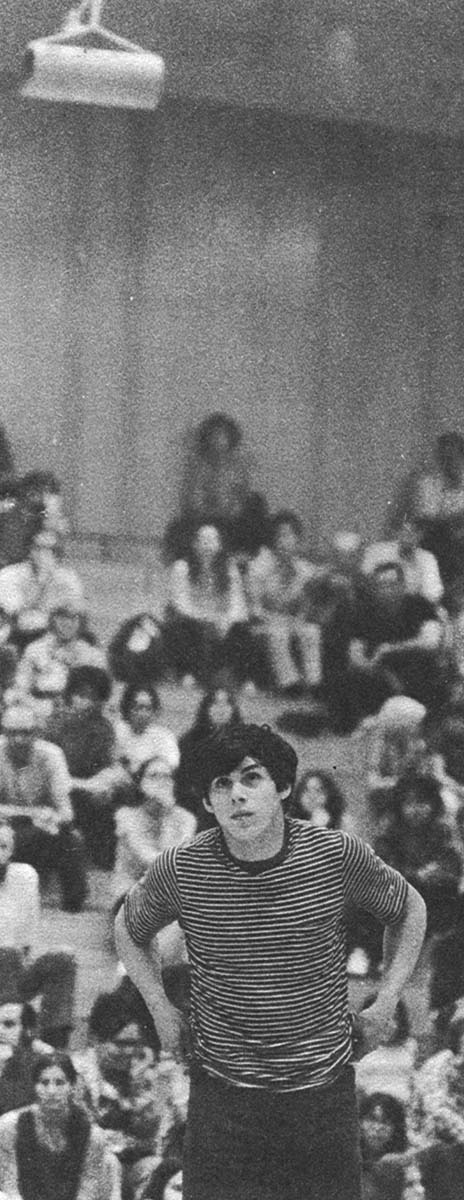

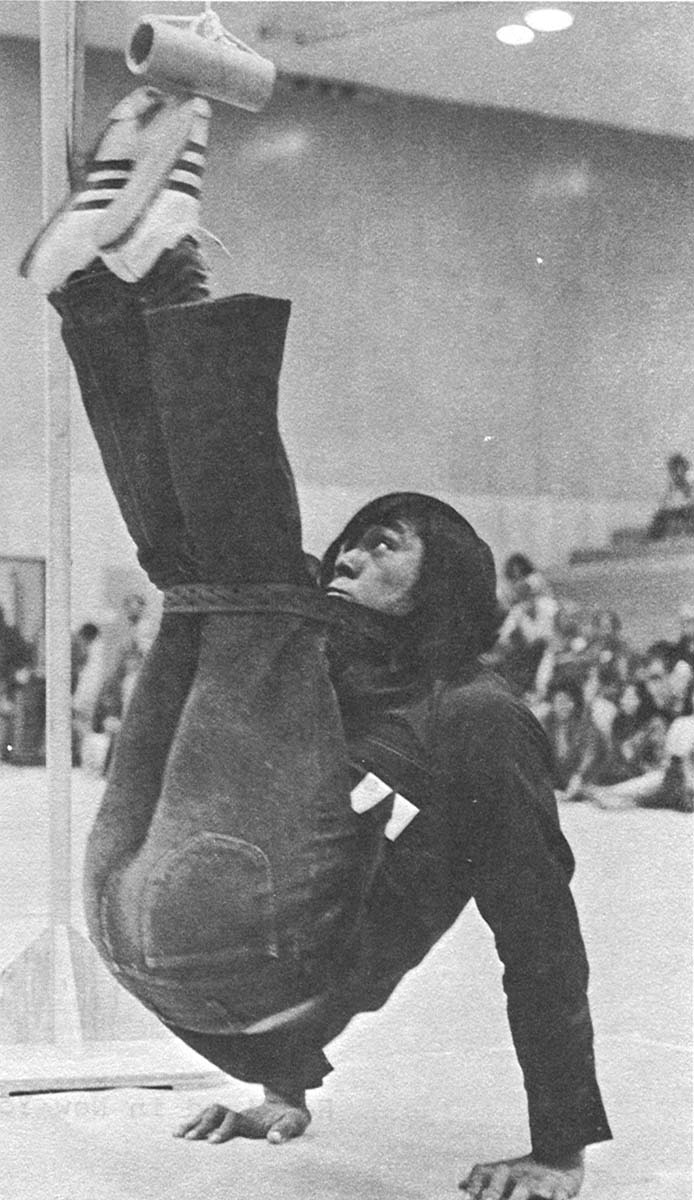

Cautiously, at first, he volunteered for some of the less spectacular games and, doing well, went on to compete in events that demand more courage and skill. In some, like the swing kick which is new to all Alaskans, he lasted until the final rounds and on the last night he triumphed by bolting down a piece of whale skin and blubber in 20 seconds to win the muktuk eating contest.

Buck Day wins the swing kick for Canada.

Katairoak did well enough to be considered a serious contender for next year’s games, but his performance meant more than simply a shot at a gold medal. He came away from this year’s Olympics more Eskimo than ever before – in his own estimation and in that of his people. He proved himself not a complacent member of a tame society but a man to match the stern criterion of the north…an Eskimo. And he’s proud to be one, which is what the Eskimo Olympics is all about.

Received in New York on August 14, 1972

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.