Galena, Alaska June 27, 1972

Today the Athabascan Indian village of Galena is the goingest, growingest village on the Yukon. Its residents enjoy a unique prosperity gained through plentiful fishing and hunting and high employment opportunity. The future looks brighter still, and it’s hard to believe that just a year ago Galena nearly came off the map.

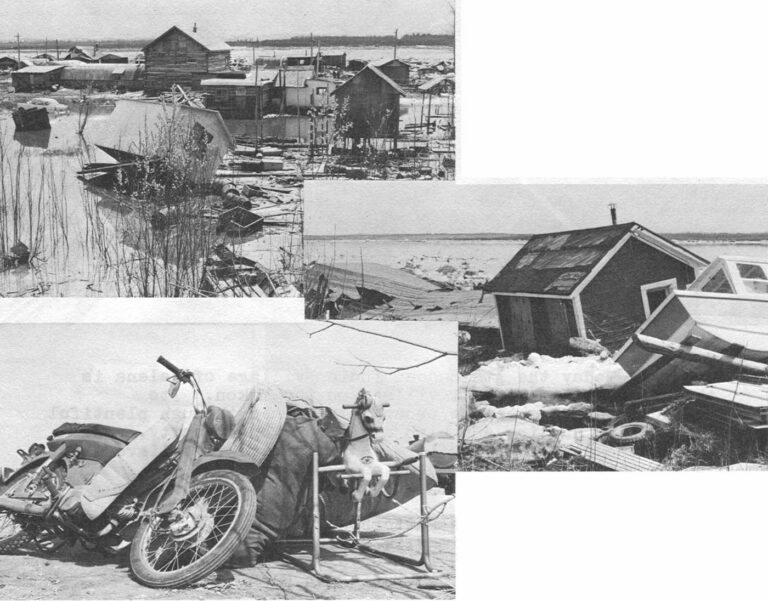

In the spring of 1971 the thawing Yukon River ran wild. Below Galena it jammed, backed up and rushed its banks, inundating the little settlement with 13 feet of water and smashing blocks of ice.

A neighboring Air Force Base sat low but dry behind a 136 foot dike that excludes the village. The commander, unsure of the holding power of his World War II vintage earth rampart, evacuated 266 servicemen and any villagers who wanted to go.

The majority of Indians declined. They knew from past experience that evacuation can be a one way trip. Someone usually turns up to rescue imperiled natives but sometimes evacuees without resources are left to find their own way home.

“Besides, we’ve lived on this river 1,000 years with no great loss of life from flooding,” reasoned Sidney Huntington, a veteran Yukon watcher. The natives along the river routinely prepare for flooding in the spring.

This was a sweeping, high water record, however, and in the early hours of May 22, Indians perched on the dilapidated dike witnessed a spectacular.

“Huge chunks pushed right into the village with absolutely nothing to stop them, knocking over log buildings, crushing houses…. We saw how formidable and powerful nature can be and how small man is by comparison.”

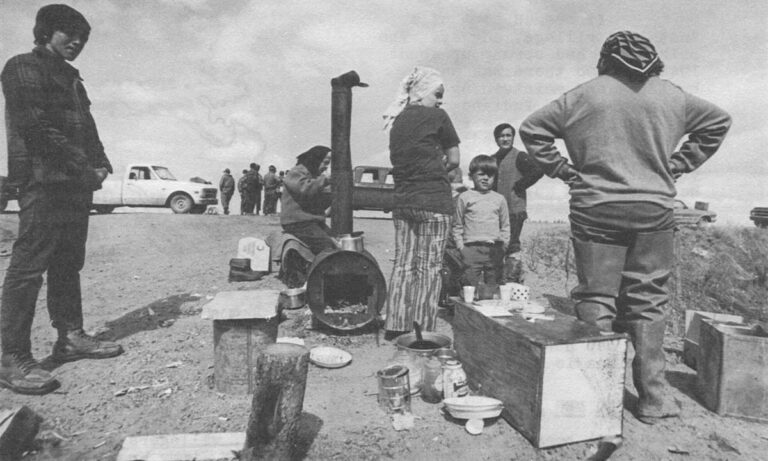

The skeleton crew left on base had been battling leaks in the dike but finally they found time to bring the Indians a hot lunch. Base staffers were also considerate about providing water and fuel but many villagers were hesitant to ask. They remained short of food, tents and blankets, and made do with no sanitary facilities until the water subsided. Then things got worse.

The village was, in the words of its civic leaders, “a devastating mess” and so were negotiations that followed on rehabilitation. Despite promises of aid from numerous government agencies, only the Small Business Administration had made good by mid-summer. The Alaska State Housing Authority, Bureau of Indian Affairs and Red Cross wallowed in red tape apparently deeper than the flood waters.

Three days later the refugees were still camped on the dike waiting for the water to recede. They were short of food because they’d cached their supplies below the new highwater mark and – although they’d been visited by the Governor, Secretary of the Air Force, the Red Cross and numerous tourists – no one had offered them so much as a cup of soup.

As a veteran Alaskan reporter, I’d covered many floods. In fact I lost my home in the deluge of 1967 which caused Fairbanks to be declared a disaster area. But the Galena mess was by far the worst I had seen and mentally I wrote the village off.

It seemed sort of a “nothing” village, anyway. The bulk of it had sprung up about 1942 because there was work building and maintaining the military base. Indians moved in from all along the river, built homes and raised families. But if you asked a Galena-born youngster where he was from held tell you Nulato or Huslia or Ruby or wherever his parents originated. Nobody was from Galena.

Something about the place struck me favorably, though. Maybe it was the spirit of the refugees I found camped on the dike. They weren’t asking any help and didn’t expect any. Anyway, this spring I went back to see how they were doing and discovered, to my astonishment, that Galena is booming.

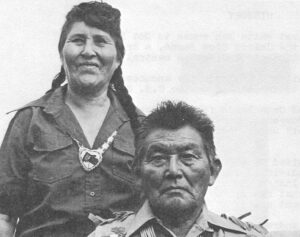

Two Strong Men and a Majority

To oversee rehabilitation of Galena, villagers gambled on two new residents. Heading the project was Jimmy Huntington, former world dog racing champion and author of a fast-selling biography, “Edge of Nowhere” (a Reader’s Digest book selection with half a dozen American and European printings). Huntington had transformed neighboring Huslia from a derelict fish camp to a model community and there was reason to hope he could do the same for Galena.

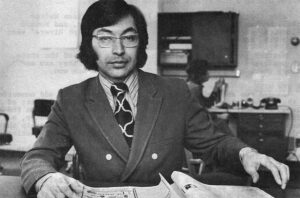

Working with him was John Sackett, also from Huslia, who had made Galena home just a year before. Sackett had been elected to the State House of Representatives at the age of 22 in 1967, served well in a seat on the powerful Finance Committee, then retired because he wanted to get back to his people. By the time the flood hit, he was deeply committed to the community.

Using a calm, no-nonsence approach, Huntington and Sackett raised $242,000 for flood rehabilitation through government agencies and the Red Cross and later returned $47,000 unused.

Villagers winterized their battered homes or replaced them with trailers, and then voted by a 98 percent majority to carve out a new building site on high, wooded ground about two miles from town. The Alaska State Housing Authority insisted they move 11 miles away to an Air Force dump site which was higher ground but villagers held out for Alexander Lake area which is within their original townsite and easy commuting distance for those who don’t wish to leave the old location.

Gravel beds are now being laid for a road system and 30 homes to be built through a federally-funded low income housing project. There are also projections for a $139,000 school, a $250,000 post office and considerable private building.

Assets

Galena has long been known as the “dirtiest, dumpiest, drinkingest town on the Yukon” but reassessment is in order.

The 1970 census reported 302 Galena residents. Today there are 400. Three-quarters of them are Athabascan. The gross annual income of the village is estimated at over $1 million. Only 25 residents are on welfare and five use food stamps.

The area is strategic – the site of the U.S. Air Force base closest to Russia and two smaller Air Force sites. Military men stationed there number about 500 and there appears to be no danger of troop pullout.

Because of the military installations, employment has always been higher in Galena than the average Indian village. Now construction of the new village and a quickening of the economy through federal settlement of the native land claims means many additional jobs.

The village has also been designated home office for a 120,000 mile region of the State Department of Health and Welfare, headquarters to service 20 villages through the Rural Alaska Community Action Program and a major hiring center for the Bureau of Land Management fire fighting program.

Because of the base airstrip, Galena has commercial jet service to major Alaskan cities and serves as a transportation hub for many smaller villages.

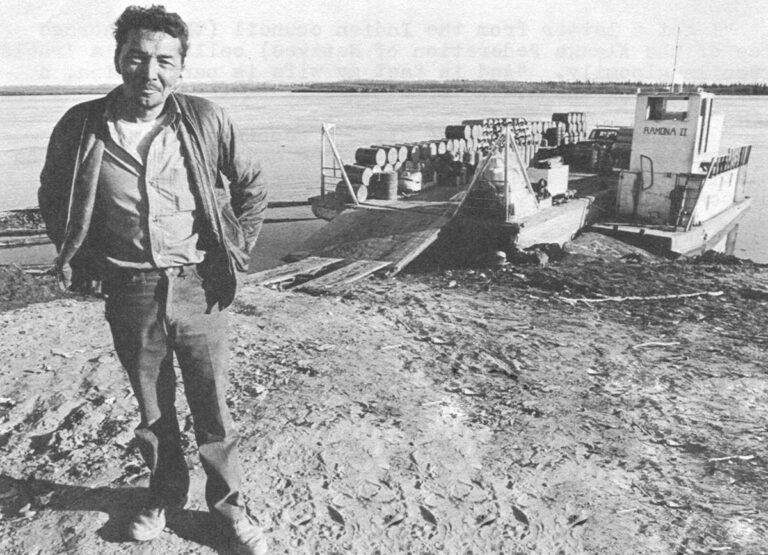

Air freight is 10 cents a pound as compared to 20 cents a pound in more remote areas of the state and the river offers competitive barge service. Freight can be shipped for as little as three and a half cents a pound from Fairbanks and five cents from Seattle.

The village boasts a good, privately owned electric company, long distance phone service and connection with five neighboring villages through a local telephone line.

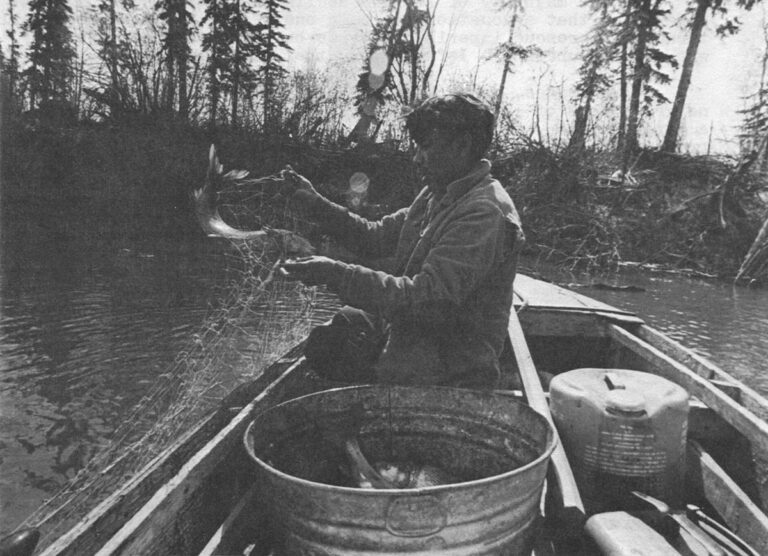

Residents can also take advantage of an excellent run of current movies at the base theater and can pick up base radio and television stations. Such conveniences make Galena far more sophisticated than most bush villages, yet its citizens still make good use of subsistence hunting and fishing.

The Indians Have It Better

“My father told me back in 1928 that the Indians have it better than anybody else,” recalls Sidney Huntington. “They have only to work hard three months of the year…. They can live all year on that.

“This is the richest, poor town in Alaska. Anyone who wants to work can work. You can live here on $10 a month for utilities and catch all you need to eat in moose and fish.”

Some Galena residents still live almost entirely off the land but Huntington isn’t one of them. He moved to the village in the ’50s to find work. Today he heads the base carpentry shop, runs a coffee shop and a moterbike dealership and supports his family of 12 quite handsomely.

He is an ardent believer in the American free enterprise system and scoffs at government handouts. Recently, working with his youngsters and a couple of friends, he raised a rugged, two story log house in nine days. (The smaller village community hall took about three months and 50 men to build.)

Sidney Huntington has elected to stay in Old Galena and is buying all the property he can along the waterfront. He predicts the new site, despite its gravel fill, will sink into the permafrost and that villagers will eventually move back to the river.

Jimmy Huntington, his brother, takes an opposite view. Now mayor of Galena, he plans to move to the new site and is working hard to see there will be no land sale there.

“It’s our intent in any way possible to stop the land grabs,” he said. “We’re suggesting leasing the land only. Not selling. That way we’ll have the income for a good many years and get on a solid footing. If the villagers can sell, soon one or two people will become landlords over the land.”

He hopes, he added, that Galena’s share of the federal native land claims settlement will be husbanded in a similar manner.

He is quick to note, however, that no one will be forced to move from the old site. The federal government has made it clear it will appropriate no funds for projects on the flood plain, but many residents have decided to stay there.

“We like to watch the old Yukon,” explained Edgar Noliner, one of Galena’s first settlers. “It scares a lot of people but we’re used to it.”

In preparation for this year’s flood he built four rafts and a little house on oil drums. The flood never materialized and he’ll be reshuffling his possessions all summer but Noliner thinks being able to keep an eye on the river is worth the trouble.

The other advantage is that property in the old village can be owned outright and is not subject to the whims of a government leaser. For this reason, the business community is hard at work rebuilding the waterfront and many private homes are going up there. The new buildings are of imaginative, flood resistant design with the core on the second floor.

Inadvertent Answer to the Problems of Transition

By creating two separate landholding systems – two villages within a village – Galena may inadvertently have stumbled on a fair solution to the problem of cultural transition.

While some native people are apt in dealing with the complexities of modern business and bureaucracy, a large percentage is not. Many, who enjoy the traditional life of subsistence hunting and fishing, wish to remain unfettered by the legalities of land ownership and regard the whole territory as their own.

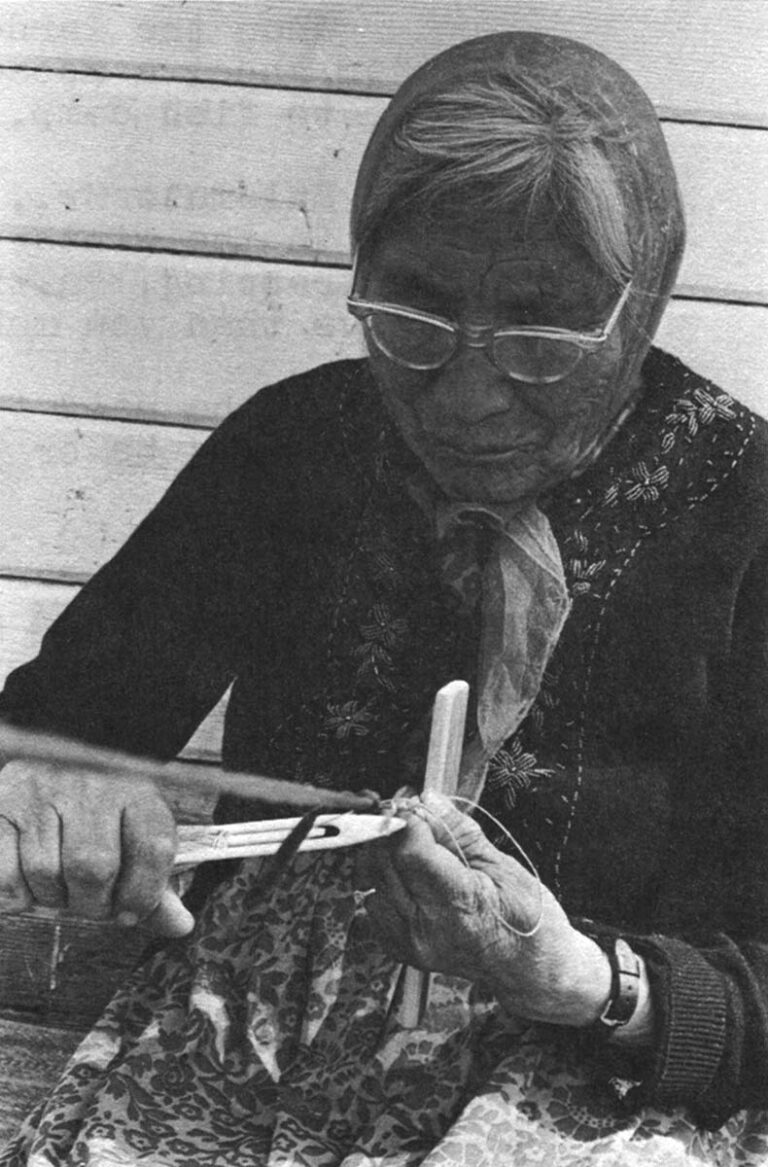

A surprising number of young Indians prefer the easy-going heritage of their elders who still speak Athabascan and knit their own fish nets to fit the width and depth of the particular river they’re fishing.

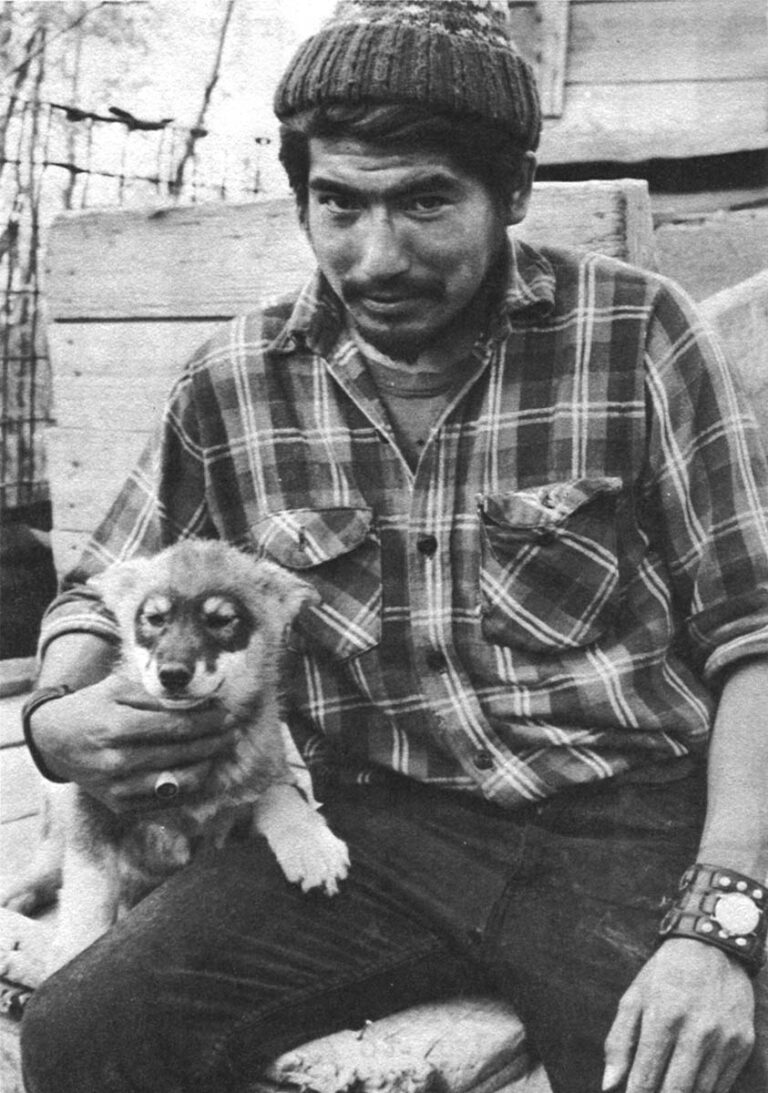

Carlson Malemute, 27, is a case in point. A veteran of Vietnam and on-the-job training (diesel engine maintenance) in Chicago, Malemute decided to come back to the Yukon.

“It’s so easy to live here,” he explained. “I can make it outside, but it’s so easy here. There”s a lot about the life I like.”

When the larder gets empty, Malemute or his brothers or father shoot a moose. In the summer the family moves 20 miles up river to fish camp.

Malemute Sr., a former dog racing champion, still raises dogs and in the winter he and his sons train them. They also do some trapping, “although it almost costs more to go out there these days than you make.”

If the need for cash arises, there are construction or fire fighting jobs or work in coastal canneries.

Malemute Sr. has legally staked out the family fish camp as his native allotment but Carlson, who was also entitled to 160 acres, filed no claim and does not regret it.

“I just don’t want to be a land owner. Don’t want to have anything to do with it.”

Many villagers are trying it both ways, leasing land in the new site and hanging on to their property in the old.

As a Galena resident and a member of a native corporation (formed under the land claims settlement) tradition-bound Athabascans will have a share in financial returns from village lands and a vote in controlling them.

An Education in Alcohol and Integration

Two additional facets of Galena living – long listed as liabilities – may turn out to be assets in coming to grips with the 20th Century.

The most heralded is Galena’s “drinking problem.” The solution in most Indian villages is prohibition but Galena offers a package store and “Hobo’s”, a very busy bar.

Frank Benson, Hobo’s owner, is proud of the fact that the village council wrote a letter on his behalf to the Alcohol Control Board when his liquor license was in jeopardy.

“If you live in any decent sized city in the United States, there’ll be bars and liquor stores,” maintains Sidney Huntington, a council member. “We might as well face reality. People are going to drink anyway. Always have.”

More subtle is the challenge of integration, or at least coexistence with a sizable white population. About a quarter of the village residents are white and, while there are occasional rifts, the attitude is basically, “live and let live” on both sides.

“Even if they hate you, they’d help you,” observes Gene Steffin, white owner of the local liquor store who’s lived on the river 20 years. “These are real good people and I stay here because I like them.”

There is occasional disgruntlement with the military which rotates its base commanders every 12 months. Col. Gerald Evans, who took command in March, has already had his share. Recently he had the unenviable job of curtailing base shopping privileges to base employees (both native and white) who live in the village.

“I got a letter from the Indian council (the Anchorage office of the Alaska Federation of Natives) calling me a ‘racist’,” he recalls gloomily. “And in fact my wife is part Indian, a Cherokee from Oklahoma.”

Evans made the ruling after a reprimand from his Inspector General who pointed out it was contrary to Air Force regulations and act of Congress for a base store to compete with local businesses.

“It’s hard to run a base in the Boonies,” he added. “The natives have always been dependent on the base which, of course, is just another headache for us.”

Villagers seem to bear Evans no particular ill will. They are becoming pretty realistic about “the system” and are trying – more than ever before – to go their own way.

Identity

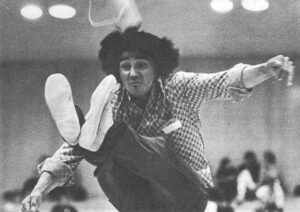

The most positive thing Galena has going for it, though, is a new sense of unity. It materialized after flood rehabilitation with the organization of the Galena Sports Association.

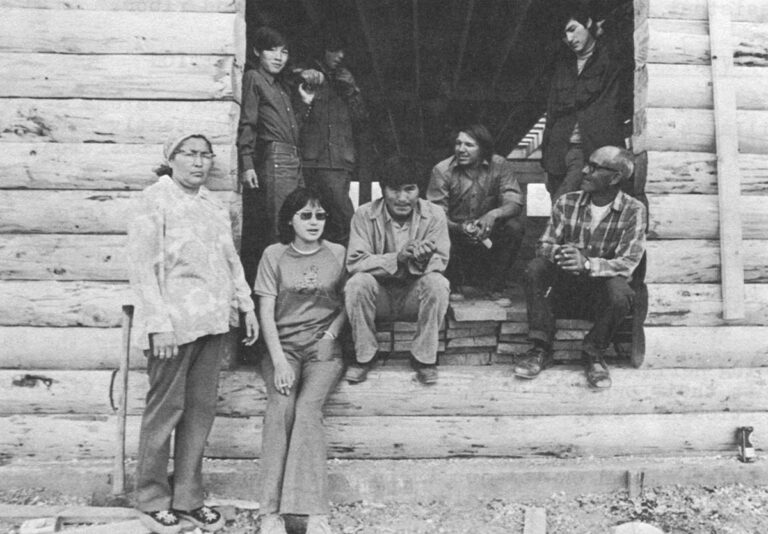

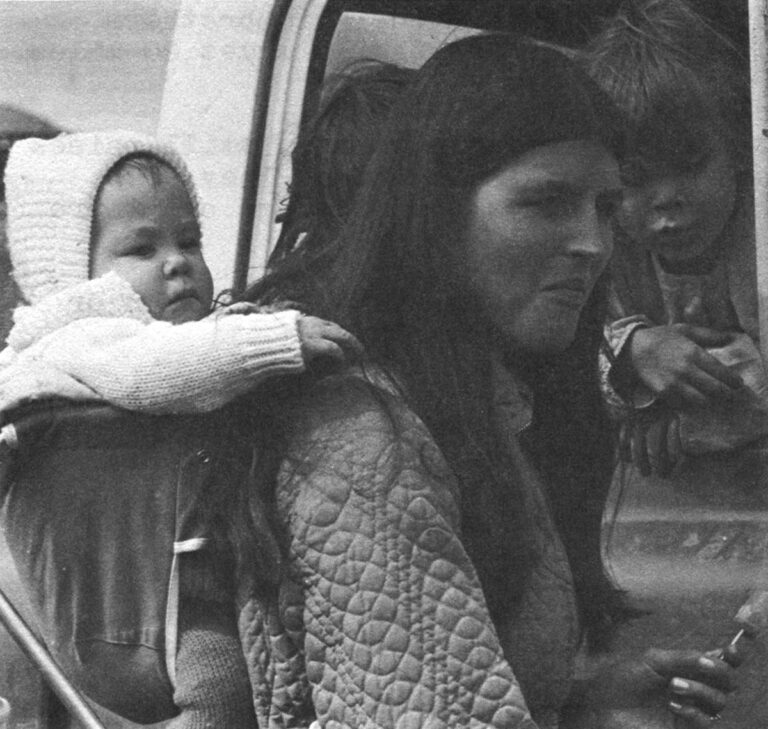

Galena Faces

Two years ago the village council undertook a sports promotion program to keep its youngsters occupied. It met with little success, but this year a group of enthusiastic villagers took over from the council and really got it rolling.

Membership now numbers over 200. They’ve rallied to support a strong bush softball league, basketball and a dog racing renaissance. Recently they raised $1,000 to make Galena turn-around point for Alaska’s classic “Yukon 800” motor boat race (which formerly stopped one village short of Galena.) Now they’re promoting the building of a village gymnasium and sports facility.

“I only wish the village council was so successful,” one of the village leaders observed. “Just ask any member of the Sports Association where he’s from and he’ll answer, ‘Galena.”‘

Received in New York on July 5, 1972.

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.