Point Hope, Alaska May 16, 1972

The Eskimo word for “whale”is a harsh whisper on the restless ice of the Chukchi Sea off Point Hope.

A light whale boat, umiak, fashioned from sealskin covered driftwood, slips into the gray water of a fog-shrouded lead.

Six men, moving as one, paddle soundlessly, cross-current; evading the sweep of jagged, fast-moving ice blocks.

Suddenly, squarely in their course, a bowhead surfaces. Its black hulk is three times the length of the boat but the Eskimos move without hesitation to attack with a hand thrust of an ancient harpoon fixed to a black powder charge.

They strike but the mammoth takes only a glancing blow, sounds and surfaces well beyond range.

The lead narrows. South wind pushes forward a crushing front of ice and the men retreat before it, dragging their umiak on a flat wooden sled.

We women of the crew watch from older, more stable ice. We have packed the food and cooking pots and are ready to break camp as we have many times. Packing, striking the tent, are habit, even to me, and I am new on the ice this season.

But my fear of the shifting floe is fresh and it is shared by the most experienced whalers. We follow an Eskimo tradition of more than 1,000 years and requirements are still primitive. We must stake our lives for our groceries.

Workable Adjustment

Point Hope is an Arctic village of 400 Eskimos who have made a remarkably workable adjustment to the 20th Century while retaining the full flavor of a rich heritage.

Theirs is probably one of the oldest continuously inhabited sites in America, set on a finger of land ideal for hunting.

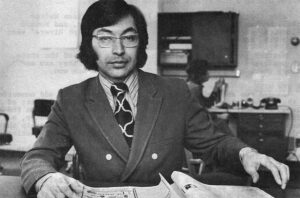

“It seemed as if nature had planned carefully at Point Hope and worked out a system of spacing the succession of animals to be hunted,” marvels Howard Rock, Eskimo editor of the Tundra Times, who was raised there. “Blessed with this bounty – whale, seal, polar bear and caribou – Point Hope is a successful and prosperous village.”

At one time its population was over 2,000, according to archaeologist John Bockstoce. About 900 A.D., Siberian Eskimos introduced the seal carcass float and the inhabitants, bankrolled by an increasing herd of caribou, began to develop techniques for hunting the abundance of whale that migrate annually past the point.

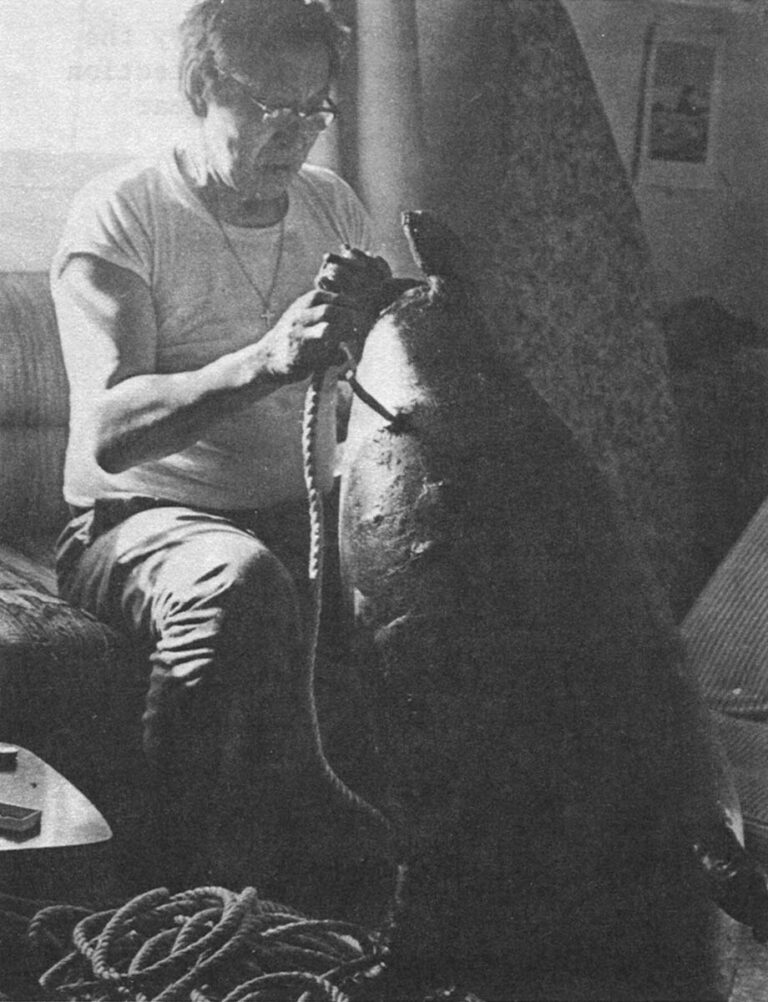

The Seal Poke Float – introduced by Siberians almost 1,000 years ago, remains in use today to keep harpooned whales from sinking. Here Laurie Kingik, a famous Point Hope hunter, readies whaling gear.v

The village flourished on this successful whaling industry with virtually no intrusion until 1886 when the first Yankee whaling station was established there.

Eskimo Chief Attungowruk imposed a demarcation line between Point Hope and Jabbertown, a colony of many races that grew around the American whaling camp. The line kept whites from whaling in Eskimo waters but didn’t stop a lively traffic in alcohol and women that grew up between the two settlements.

In 1889 Lieut. Commander C. H. Stockton of a U.S. revenue cutter found Point Hopers “in a most degraded state, physically, mentally and spiritually” as the result of contact with the white man.

“Each visit of a whaling ship was followed by riot and drunkenness; the women were carried off to serve the lusts of the sailors and officers,” Stockton reported to the mission division of the Episcopal Church. “Although under the flag of the United States, there was nothing but chaos and paganism.”

In response, the Episcopalians dispatched The Rev. Dr. John Driggs to the rescue. The Point Hope people, still very much in control of their boundaries, refused to let the missionary land in the village and suggested he camp a couple of miles up the beach until they decided whether to kill him or keep him.

Luckily, Dr, Driggs was an excellent physician who put medicine and education ahead of proselytizing. He managed to cure a member of the chief’s family after the local witch doctor had given up and soon enticed villagers to English classes by offering snacks.

Driggs ministered to the people of Point Hope until 1908 when the church wrote him off as “eccentric.” He had moved from a frame house (advocated by the church as a needed trapping of civilization) to a native sod house which was warmer, decreed that no young Eskimo man could attend school in good hunting weather (he offered make-up classes at night) and traveled widely by dog team with Eskimo hunters.

Missionaries who followed denounced Eskimo traditions, forbade dancing, the hunting of whales on Sunday and carving of effigies, but the natives gave only token attention. They developed respect for higher education and became fervent church goers, but they clung stubbornly to the best of their old culture.

In 1932 the church helped the community experiment in self government and in 1940 Point Hope incorporated.

During World War II, some Point Hope men got jobs in defense construction and, in the 50s, on the Distant Early Warning System. (In 1951 Point Hopers brought home $30,000 from a single defense contract and last year, according to a man who helped figure income tax there, at least 10 families reported incomes of $18,000.)

Because of their job experience many Point Hope workers are union members, which has enabled them to solve the problems of job hunting that stymies natives in other isolated areas.

And, although gains from outside employment pour into Point Hope, the Eskimos continue to maintain themselves by subsistence hunting. A good hunter is still the most respected of men and, besides, wild, native food is preferred to white man’s fare.

As a result, the skill of Point Hope’s young hunters is as polished as that of their fathers and forefathers at a like age. In addition, these young people are bilingual and fit easily into the white culture, while retraining great pride in being Eskimo.

Congress Could Destroy A Lifestyle

Currently Congress is considering legislation that could destroy the unique balance of cultures that Point Hope enjoys. The Sea Mammal Protection Act, which has already passed the U.S. House, would put a five to 15 year moratorium on hunting of sea mammals on which the village depends.

While the bill allows for subsistence hunting, it precludes the taking of endangered species and some scientists believe the bowhead whale, a mainstay of the village diet, should be included. Trading and interstate commerce in sea mammal products would not be allowed, either, which would be serious blow to the economy.

To discover the impact of this legislation, I have been living with Point Hope Eskimo family and serving as assistant cook and dishwasher on their whaling crew.

Suburbia Misplaced

The village looks like a modest suburbia misplaced on the tundra some 140 miles north of the Arctic Circle. All the homes, with the exception of one sod dwelling, are frame construction, and even the sod house is wired with electricity.

There is a large school with a stout arsenal of progressive teaching aids including film clips of “Sesame Street.” A modern cooperative store has just been built and there is a movie theater which shows a fairly good run of films.

There is no sewer or water system but plans are being made to move the village to an erosion free site and build a model city that would include plumbing. The Point Hope Council is far-sighted and progressive and has been unusually successful in securing government grants to meet the needs of the community.

Come whaling season, however, Point Hope reverts to its past.

The Hard Way To Catch A Whale

The first water opened April 12 and the village became tense with the excitement of getting out there.

One week earlier the women had sewed new skin covers of oogruk, the bearded seal, over the boat frames. Now the preacher arrived by snow machine to bless our craft. The crew knelt for a prayer in terse Eskimo and we were away with “Amen.” Two dog teams went first, followed by snow machines pulling our boat and grub box.

The ice is a harsh, ever changing world, bounded by towering pressure ridges of frozen blocks the size of deepfreezes. Our first lead was a narrow span of black water that spun off dark mists shot with sun.

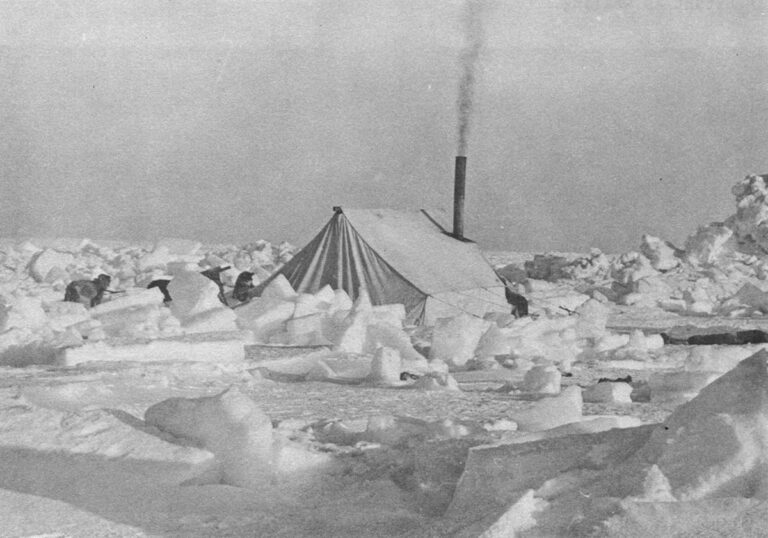

The men quickly anchored the guy ropes of our tent to hefty ice blocks. Three plywood planks were laid as flooring over the “Windex” blue of our frozen perch and a stove, fashioned from an oil drum, puffed smoke through a pipe bedded with a shield in the canvas roof.

Outside, a sharp wind tore from the northwest, adding sting to the sub-zero temperature. Inside, secure with a large dishpan of seal blubber chunks to feed the stove, we drank tea and waited for the wind to drop.

My captain, Bernard Nash, waited with apparent calm but he is tightly wound. This is his second year as a captain and he has yet to get his whale. He’s an excellent hunter and was harpoon man on the crew that killed Point Hope’s record whale, a 65 footer. But last year he left his crew part way through the season to take a construction job outside the village. This year’s hunt has been outfitted at a cost of nearly $700 from his income tax refund, unemployment checks and food stamps. It’s important that we score.

Our crew includes Gus Kowunna Sr., an ice expert of extraordinary toughness and excellent good humor; Sam Nash, the captain’s son who is bookish but a fine oarsman; and Earl Kingik, veteran of Vietnam who is the son of a famous hunter and a credit to the tradition.

Isaac Killigvuk, Norman Omnik and Morris Oviok have also thrown in their lot with Nash for a second year. They have all lived outside Alaska but returned home to hunt. They are young, savvy and have been trained to the ice from childhood.

A 20th Century touch is our own “live-in” archaeologist, John Bockstoce, who claims to be along just for the fun of it. I tend to believe him because this is his second year as a crew member. He’s a former Olympic rower and he really enjoys the life on the ice.

And there is our “boy”, Gussy Kowunna Jr., 13, who has the hardest lot. He fetches and carries, stays up all night to tend the stove, does all the dirty work. Yet, in reality, he is an apprentice whaler and will get a man-sized share of the kill. And he dares hope that next year he will take his place at a paddle.

His sister, Esther Kingik Bosta, wrote a note to his teacher that read simply, “Gussy is excused to go whaling.” He will be on the ice six weeks.

Esther is head cook; well traveled, educated and currently a city dweller. But she came home for whaling because she likes the excitement of the hunt and is sought after as a cook.

On both sides of us white tents are strung out along the lead. They are headquarters for 11 more crews, all of similar composition.

The Mark Of A Man

Among Point Hopers it’s the mark of a man to go without sleep for three days, and, even at the beginning of the season when the weather is savagely cold, the hunters shun the comfort of the tent to keep watch at the water’s edge.

When the whales come through en masse, the men will not stop to eat and may spend five straight hours at their paddles. They return to us crusted with frozen brine and send the boy to the tent to exchange frozen gloves for dry.

Whales can appear just about any time there’s open water. Sometimes they surface in a lead so small you wouldn’t expect a duck to land there. Sometimes they steam past in the dark and sometimes in a blanket of fog when floating ice is unpredictable and dangerous.

The bowheads can travel about 50 miles an hour, Kowunna estimates. A boat will go 12 miles an hour or maybe faster if the crew is good.

“When you see a whale you gotta work, work, work. Work like hell to catch him…. Work until you sweat,” he says.

You must strike from behind or directly in front, for a whale’s eyes are on the sides and if he sees you, he’ll move out. Our harpoon and darting guns with black powder bombs were patented in the 1800s and they are modest weapons. The crew needs the advantage of surprise.

Women’s lot is less exciting than the men’s, but we are an important support team. Cooking on the oil drum stove and a Coleman burner, we turn out endless meals of caribou stew, boiled polar bear, muktuk (edible skin of the whale which is delicious with mustard) and eider duck.

These meals are usually served only with pilot bread (a thick, bland cracker) and yeast doughnuts which we make by the gross in a dishpan, fashioning them with our fingers without the aid of a cutter.

I’m a little leery of the native foods but find I like most of them. Despite the fact I have eaten only three helpings of vegetables in a month (none of them fresh) I never felt healthier.

I’m clumsy. My doughnuts come out lopsided. But Ruth, the captain’s wife, and Esther are patient. Soon I’m skinning eider ducks.

It is also our job to cut blubber for the stove, babysit the dog teams and carry meals down to our men on watch. Often we walk five to 15 miles over rough ice. After a day like that we can sleep anywhere, and when the whales run thick, we sleep on the ice.

We were there for the first whale, watched the men go out and followed them with our eyes until they vanished on the horizon. For two hours we waited into darkness and finally, far off, we heard the echoing cheers of our crew and five others.

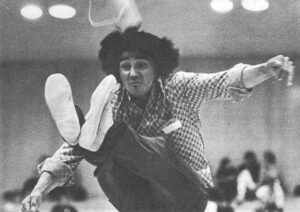

We cheered and yelled back; laughed and cried and hugged one another. The boys did a weird, happy combination of Eskimo and square dance, swinging each other around and singing.

The tension was gone at last. It was the first time in two weary weeks on the ice that the women had really laughed. We knew now we would eat.

It was not our whale but we had helped. We got a share. Then we went back to our watch.

The wind shifted, threatened to push our camp to Siberia. An automatic vacation – and I used the time in the village to interview the old-timers.

Even After All These Years

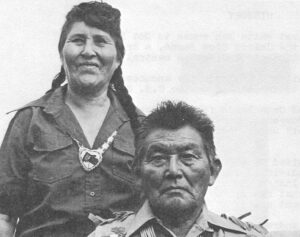

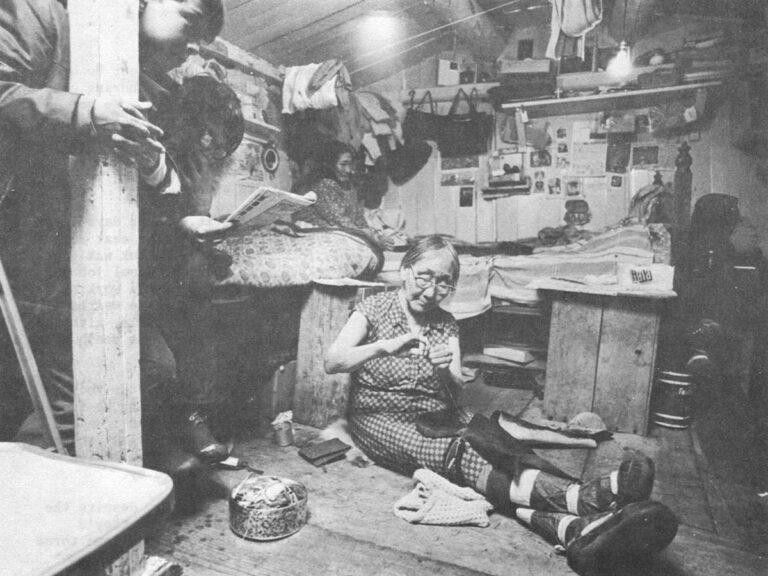

Nanny Ooyahtuonah, last resident of a sod house, can remember when women wore trading beads strung through the base of the nose and Dr. Driggs was still teaching.

Her long entry tunnel is shored up with mold greened whale ribs and filled with the flipper of a 57 foot whale killed by her son-in-law. She likes whale meat best, even after all these years, she tells me as she sits straight legged on the floor sewing waterproof boots from seal skin.

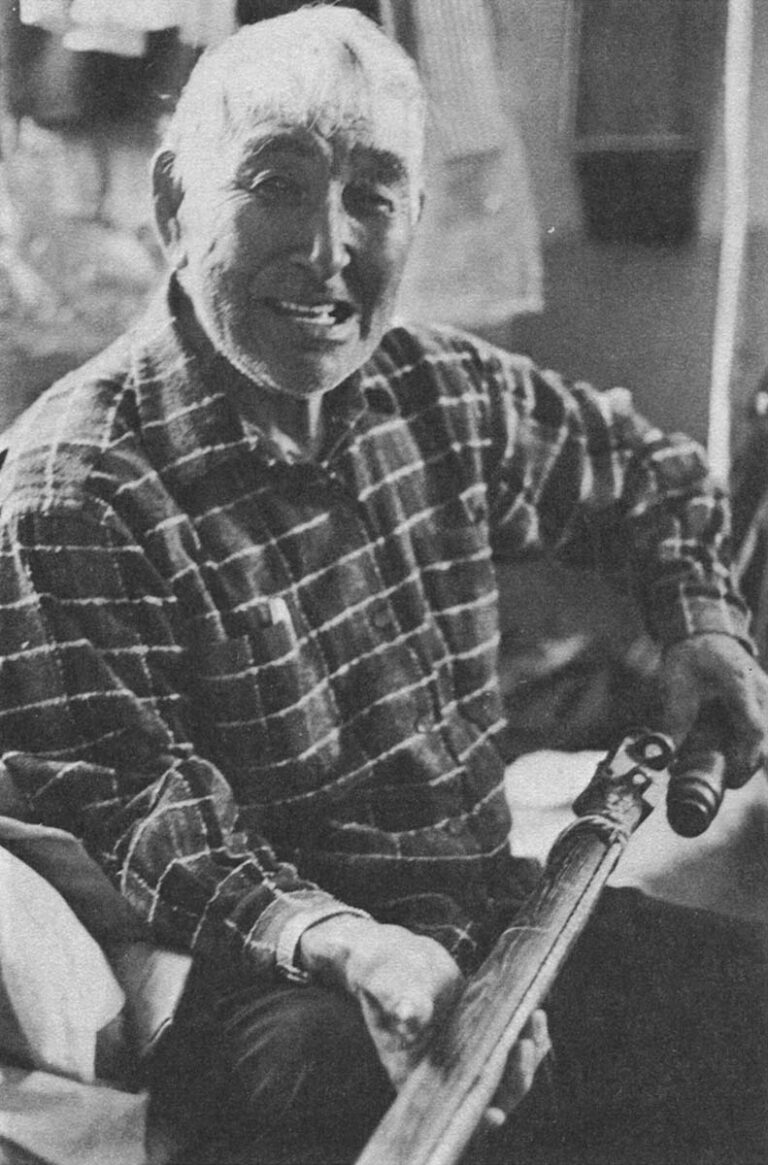

And there is Jimmy Killigivuk, 81, who still is captain of a whale boat although a stiff leg keeps him off the ice in bad weather. He’s hunting with some of the whaling gear he bought second hand back in 1909.

Jimmy tells of the time he and three teenage girls went out and harpooned a whale and it’s true. Just as Robert Tuckfield got one of his 23 whales almost single handed and Sammy’s grandfather nearly drowned in the whaling accident that killed Sam’s great-grandfather.

Jimmy Killigivuk – with one of his early darting guns. It is still in use.

The whole village is whale happy. The children practice throwing broomstick harpoons into snowbanks. Conversations are all on the catch and near misses. Visitors who come to the village on business give up and go visit the ice camps. We’re all back out there as soon as the south wind stops. There is little open water and it starts to freeze. Laboriously our men smash the ice away with their paddles but it defeats them, freezes thick enough in two days to support skilled walkers, and they move out cautiously to open water a mile beyond our tent.

One day we took food to them only to evacuate in mid-meal and watch our picnic site become open water. Two of our crew fell in, hauled themselves out, changed clothes and went back to hunt.

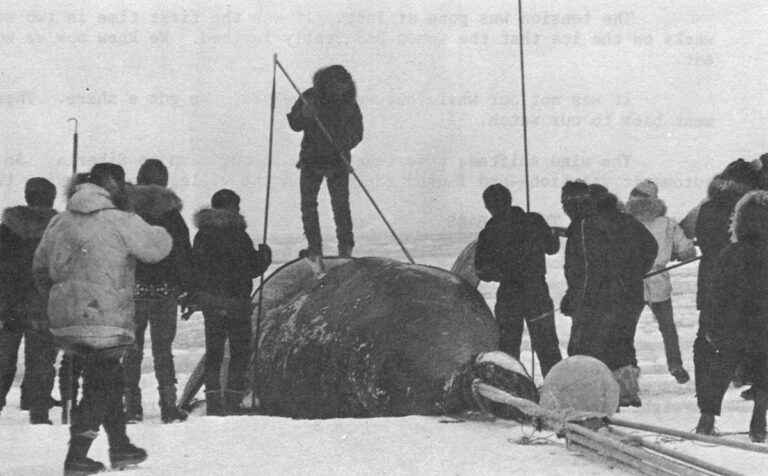

And we scored. A 38 foot bowhead shouldered in close to a neighboring crew who harpooned it from the ice. We got our harpoon in, too. Rope was fetched to secure the animal but it revived despite the fact it had taken six bombs, spouted blood all over Gus Kowunna Sr. who was standing on it and sounded to die alone.

We searched for it. Three days later it surfaced, a “stinker.” The meat was fit only for dogs but the muktuk was good and we helped with the long, foul job of butchering. With nearly 70 men working it took over 12 hours. A whale weighs a ton a foot and is hard to handle, although the Japanese factory-type ships can butcher a whale an hour.

The weather turned warm. We took breakfast to the men one morning to find our boat out. Ruth, Esther and I waited by the lead, enjoying the sun and excitement as 20 bowheads and dozens of kittenish little beluga whales cruised by.

Our men came home happy, despite the fact it was late afternoon and they’d fasted 14 hours. They’d helped land three whales – one a 57 footer.

But the South wind came in while we were butchering, pushed in tons of ice that buried the big whale before we got to it. The crews escaped with no time to spare.

We regrouped, waited out the weather and went back to find old landmarks missing and our leads frozen. We busied ourselves shooting eider ducks and now the water is open again and we hope our luck will be better.

How Much Is It Worth?

“How much is a whale worth to you in groceries?’ I asked the captain.

“Why, 30 to 60 tons,” he said. “And we will use every bit of it, too. Everything but the liver and lungs which will go to the dogs.”

“It is our tradition,” Morris Oviok said. “The tradition of our forefathers.” That’s why he came back from school in California to hunt.

“We’ve got a lot of boys down on the ice,” admitted Gussy’s teacher. “Sure they missa lot of classes, but really, I think they’re better off than the kids who don’t go and sit here thinking about it. A ‘boy’ learns a lot on the ice. It’s a real education.”

“Our very lives revolve around the migration cycle of oceanic mammals,” Davis Stone testified for the Point Hope council at a Congressional hearing on the Sea Mammal Protection Act, last week.

“There are virtually no jobs available in Point Hope. The 1970 Manpower survey showed 64 percent of our people have an average income under $3,000.

“The cost of living at Point Hope is double that of Seattle. Obviously it is virtually impossible to meet the cost of oil, rent, lights and food without any monetary supply. Any money that can be gained from our limited use of the sea mammal products is sorely needed.”

Although Point Hope is the second largest whaling community in Alaska, Stone said the native store purchased only 2,000 pounds of muktuk for resale last season. This averages $23.53 gain per person, less than the cost of a barrel of stove oil. He added that they utilize the whole animal except for the skull which they sink by tradition.

“We have always hunted only for our need. We have been wise enough not to overkill. Is it fair to destroy our cultural heritage and our lifestyle by stopping all utilization of these mammals?” he asked.

But it is summed up best, perhaps, by Thomas Robinson, the principal teacher at Point Hope.

“If you feel the need of being a Savior, this is not the place to come,” he began cryptically. “This village takes care of its own problems….

“I don’t know what a village does when it doesn’t have something as important as whaling.”

Received in New York on May 22, 1972.

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.