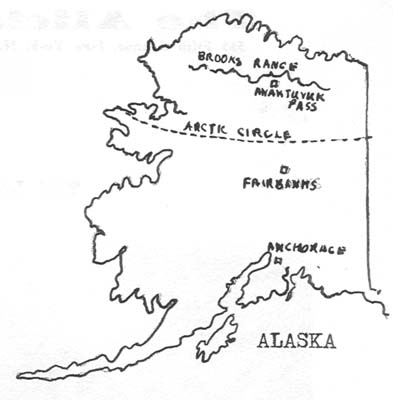

Anchorage, Alaska March 24, 1972

The people of Anaktuvuk Pass were the last of Alaska’s independent Eskimos. For centuries they followed the track of the migratory caribou through the Brooks Range far north of the Arctic Circle.

They were proud to call themselves “Inupiat” -The Real People. They lived wholly by hunting; subsisted in the earth’s fiercest cold in tents of caribou skins and splendid fur clothing designed by their forefathers.

At the end of the century whale hunters killed off the game, forcing the Eskimos to abandon the mountains and camp with coastal cousins. There they discovered the white man and the civilization he was introducing, but the Anaktuvuk people remained aloof. When the caribou herds grew strong enough in the late 30s, a small nucleus of families moved back into the mountains and more joined them as the game increased.

Long after other Eskimos had settled into the white man’s ways, the Anaktuvuk people enjoyed a free, nomadic life. To the east their Canadian counterparts grew dependent on the traders, dulled their hunting skills and starved by the hundreds. The Inupiat knew hard times, too, but their traditions sustained them.

Then, in 1961, they decided a school must be built. The influence of the white man had at last penetrated the mountains. There was no arguing. It was obvious that the next generation would need a white man’s education, but no one dreamed how high the cost would be.

The state of Alaska built Anaktuvuk a fine school and federal funds were provided to run it but there was a catch. The Inupiat had to give up their nomadic lifestyle in order for their youngsters to attend.

Children could not be excused from classes to follow the caribou herds and parents could not abandon their children. To live the Inupiat must hunt. To hunt they must travel, but the school held them fast.

Transition

February, 1972, I lived with the Inupiat in their now-permanent settlement at Anaktuvuk Pass. The population totaled 112 with 108 Eskimos, two white teachers, one white man married to a native and me, also white. I was accepted (although not without reservations) because I work for a native newspaper.

I rented an 11 by 13 foot plywood house that had previously been occupied by a family of five. It boasted caribou fur weather stripping, a cot, a table, a box, a stove and a kerosene lamp. With me I’d brought a sleeping bag, two changes of clothing, a mess kit and $58 worth of groceries which had cost an additional $30 to ship air freight. My Eskimo landlord loaned me a kettle in which to melt snow for my water supply.

The Eskimos call February “Sikinaasugruk”, the month of longer sunshine, but it is also the coldest, hungriest month of their year. This year is tougher than most. The wolves in the hunters’ traps are found eaten by other wolves and dogs sometimes wail in the night for want of food.

Over 90 percent of the village is on welfare. Itts taken for granted now that welfare comes with this season as surely as snow blows through the Pass. But food stamps are useless when the supply plane can’t land and the meat caches stand nearly empty.

Over 90 percent of the village is on welfare. Itts taken for granted now that welfare comes with this season as surely as snow blows through the Pass. But food stamps are useless when the supply plane can’t land and the meat caches stand nearly empty.

“It’s too bad we can’t eat the ravens,” joked Rachel Sikvayugak, who with her husband, is in charge of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) General Assistance Program. “We would have plenty of fresh meat if we ate ravens.”

Only unpalatable ravens remain. The game has long since learned to detour the village.

February was a hard month in the old days, too, but the people were free to follow the game. Rachel remembers because she was raised by nomadic parents.

“Then whole families camped for days at a time. But now, because of the school, it’s impossible and the youngsters don’t get much chance to learn to hunt and trap,” she said.

Heat is almost as much of a problem as food. The willow supply that once seemed ample fuel, gave out in the mid-60s and kerosene runs $74 to $64 for a 55 gallon drum that won’t last a month.

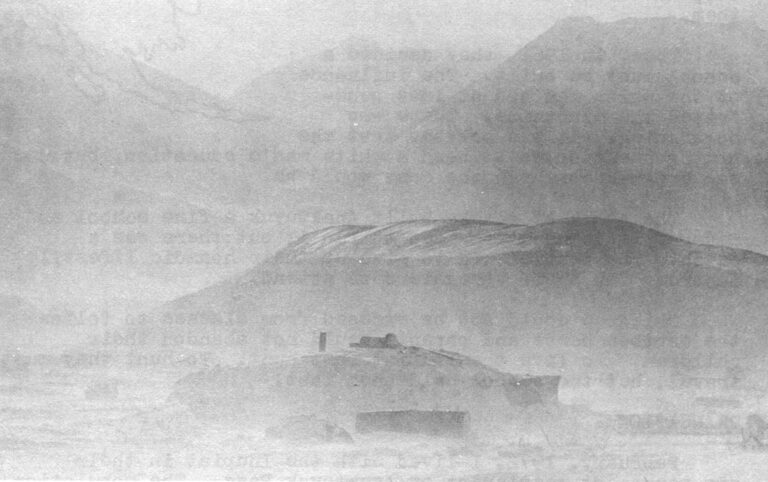

The winter wind blows strong. Last year it took the roof of the school. Sometimes the gusts were so fierce I awakened from frightened dreams to find my fire had been snuffed out and room temperature was below zero.

At -50º outside with a north wind my hut would never 0 heat above 40º. When it did warm up the foundation shifted on the permafrost and the stovepipe threatened to fall out. Once, while I was being visited by 15 youngsters, the oil burner back vented and blew up, nearly igniting the plywood and linoleum at its base and choking us with black smoke.

None of these things are unusual, the neighbors assured me. Even those lucky enough to own the less drafty sod houses, shared my stove problems.

Togetherness

I settled quickly into the village pattern of semi-communal living. Everyone visits someone all the time. Families are generous in sharing their children.

Almost every child in the village tried on my hat, used my hairbrush, counted my pencils and inquired in embarrassing detail into my marital status.

They were delighted to learn I was single for they have few marriageable women in the village. The young girls must go outside for high school and too many marry outside. Currently eight eligible bachelors are left with no one to court and they need wives to cook, scrape and tan the furs, sew their boots and parkas and tend their dogs.

“Drink plenty of strong tea and you’ll be married within the year,” Lela Ahgook, the postmistress, assured me, for it is too rough a country for a woman to live long alone. I needed someone to hunt for me, to fetch ice and fix my stove.

One day, completely exhausted and suffering from a bad cold (contracted, no doubt, from the chill of a single bed) I put a sign on my door reading, “I am asleep with a cold. Visitors are not welcome until I wake up.”

It didn’t work because a lot of people can’t read and they stopped in to ask what the trouble was.

One of the greatest disservices an Inupiat can do another, apparently, is let him get lonesome and being lonesome is synonymous with being alone.

“What’s privacy,”one of the youngsters asked one evening.

“Privacy is being able to lock your door and have nobody bother you,” an older girl explained.

“What if they look through the window?”

“Pull the curtains.”

He looked distressed. “We don’t have any curtains,” he said.

“Well, take off your pants and hang them up,” she advised.

Most of the homes are one room (it would be madness to try to heat more) with one very large bed and maybe cots for the older children. There is a growing concept of personal property but people still look out for one another more than most.

“Maybe that’s why all our stores fail,” one villager reasoned. “When people are hungry you can’t deny them food just because they have no money.”

Several families, who moved from Anaktuvuk to larger settlements, have returned because they miss the companionship of the village and believe it is a better place to raise children.

The Best of the Old Ways Prevail

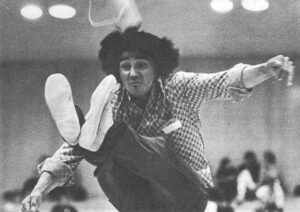

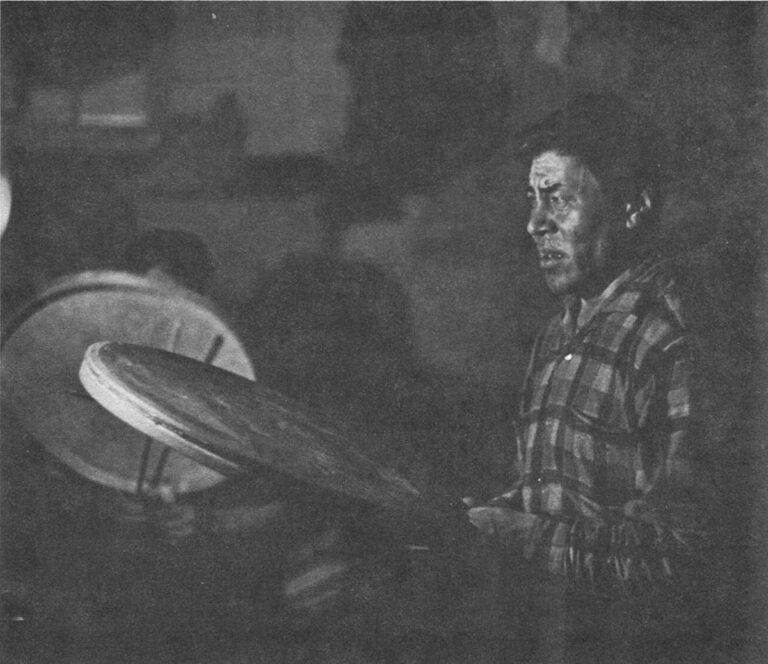

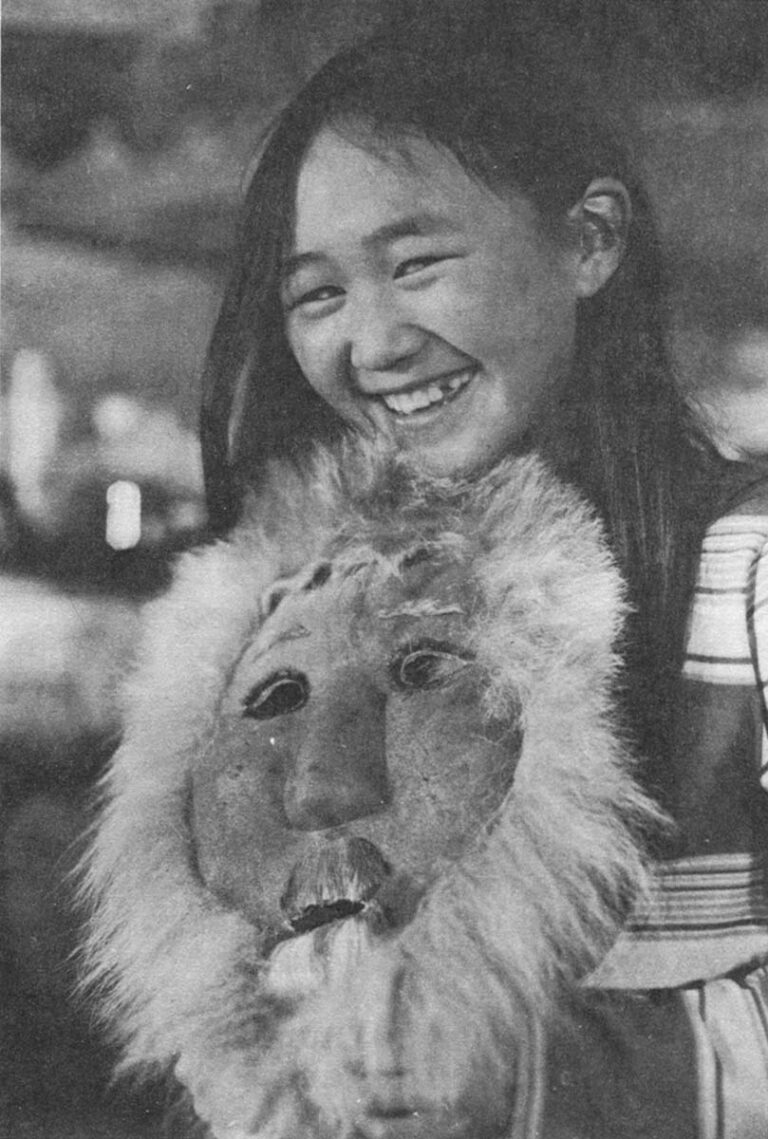

The Best of the Old Ways Prevail – The girls of Anaktuvuk still prefer long, fur lined parkas and babysit the easy way, which is traditional. Inupiat remember the old songs to the beat of skin drums.

Here there is a high premium on honesty and cleanliness. By cheerful, mutual consent there is no drinking and poker playing is outlawed. There’s a passion for social card games like “Snerts” and “Dirty 8” and the village council schedules a steady round of activities like church, bingo, Audie Murphy movies, pool, women’s club, more Audie Murphy movies…

Threatened Existence

But no amount of community planning can seem to overcome the problems that threaten the very existence of the village.

“Their fate doesn’t seem to be in their own hands,” observed one BIA official. “They have to call for help so often. They’re always in the news with airlifts of food, fuel, dog food…. One day the government is going to have to decide whether it is going to continue to subsidize Anaktuvuk or let it go.”

When the fire wood gave out in the mid-60s, the villagers considered relocating and decided – against the wishes of most government agencies supporting them – to stay in the Pass. The BIA gave them oil stoves with a three year supply of fuel which didn’t solve the problem but merely postponed confrontation.

Today the nearest timber for fuel and building is 40 miles away. Game is 60 miles off and the average family needs a caribou a week for food and fur clothing.

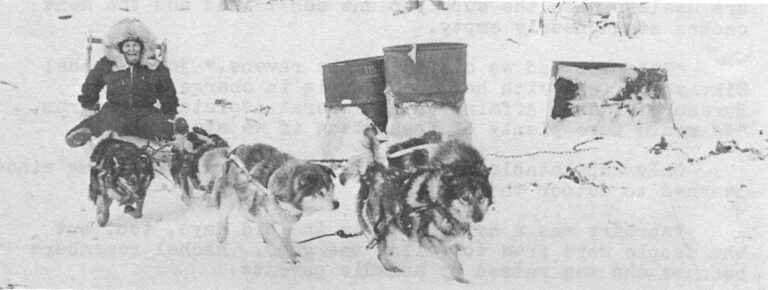

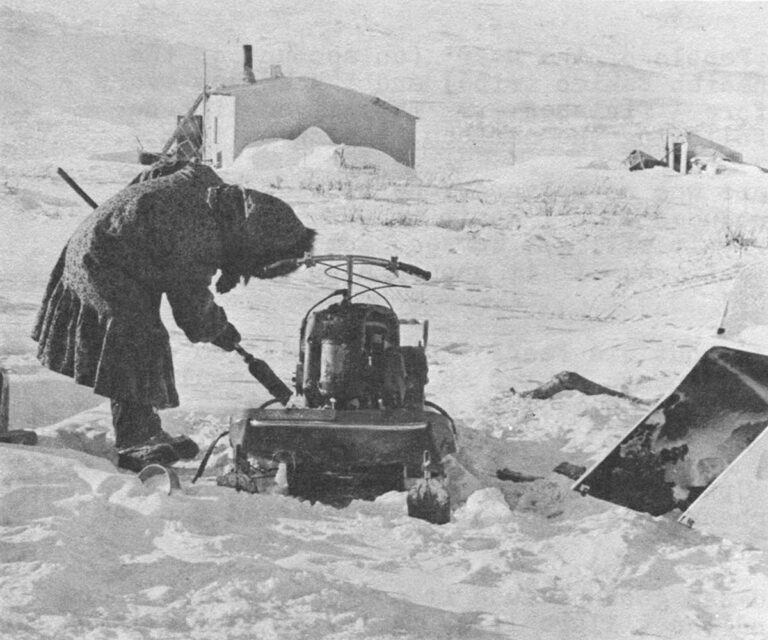

Snow machines have replaced all but three working dog teams which somewhat relieves the burden of hunting, but the machines require $8 worth of gas for a three hour run plus more money for oil and maintenance.

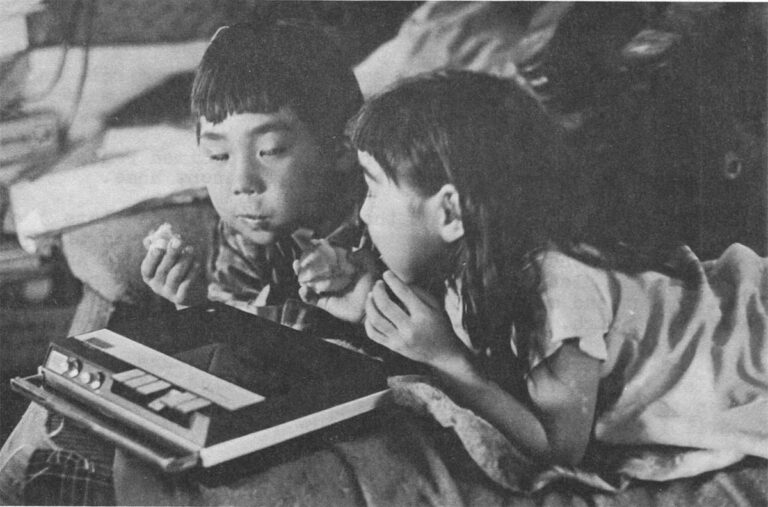

Money is also needed increasingly as people develop a taste for commercial clothing, Dr. Pepper and cassette recorders.

Jobs are few. Some men have successfully sought work in Fairbanks, the closest city, or even as far away as California and Illinois where the BIA offers on-the-job training, but the Eskimos miss the Arctic and usually return.

Those who remain in the village can sometimes make $1,500 to $3,000 a summer as fire fighters but there’s no counting on a dry year. Nor will these paychecks last the winter for the concept of saving is alien to these people.

Another source of income is a small but growing mask-making industry. The unique faces were originated for an Eskimo dance a few years ago by two Anaktuvuk hunters and are now sought after by tourists. However the masks are made from caribou hides and so the industry, like subsistence, depends on caribou migration which sometimes fails the village and may soon be threatened by oil development on the North Slope.

Anaktuvuk Mask Making First raw caribou hide must be scraped. Then it is shaped over wooden frames like those made by John Hugo (below). The hides are soaked in water and tea and emerge, after a little tailoring, looking human.

Roosevelt Paneak, in his mid-20s and the son of one of the first families to settle in Anaktuvuk, sums up the general feeling of his Inupiat generation.

“I am lucky to have lived before it began to change. We moved. Lived in dome shaped tents – caribou fur on the inside, canvas outside. There were six of us. It was a good life.

“I read ‘The People of the Deer’ (an account of the extinction of a Canadian Eskimo tribe) and I knew how every scene would end before I finished it. They lived like our grandfathers did, following the caribou, living on them…

“At first there was no welfare,” he recalled. “One of the traders introduced it. I don’t know what is going to happen but I worry it will get worse. Some people have grown to depend on welfare. If it should stop I don’t know what they’d do.”

He spoke also about his fears that the children were not learning to speak enough Eskimo and that they would not know how to hunt and trap as well as their fathers.

Louisa Morry, slightly younger, talked of alternatives. She had been in an Upward Bound program and later gone to high school in Fairbanks where she nearly qualified for the Olympic ski team.

“Upward Bound was good because it made me realize there was something beyond the village life. A lot of people think they can’t make it anywhere but in the village but there are a lot of good things in the city.”

As well as she knew them, though, she elected to come home and marry a local man. Now she teaches “Children’s Cache”, a modified headstart program for village preschoolers.

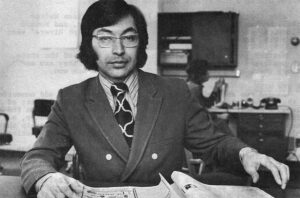

Jacob Ahgook,a personable, well-educated Inupiat in his early 20s, came home after a successful work stint in Chicago.

“I couldn’t stay away because hardship exists,” he explained. “Hardship for my relatives, my family.”

He was lucky enough to find a job as a federal weather observer for Anaktuvuk so he doesn’t hunt and trap as much as the average, but he does value the old traditions.

“We may think about bringing back the old ways. Not just here. If you go to Oklahoma you will see the girls in long skirts…the boys in Indian dress. We may bring it back here. An Eskimo dance on the holidays…Eskimo language taught in the school.”

Contrasts

Jacob was just elected to the village council where such 20th century topics as handling the native land claims settlement and formation of an Arctic Slope borough with the power to tax are discussed in unhurried Eskimo.

I watched with fascination one morning as Roosevelt Paneak shaved with a battery powered razor, followed up with “English Leather”, then donned his caribou fur parka to go hunting.

At women’s club my neighbors sewed traditional caribou fur footwear (yet to be surpassed for warmth by commercial boots) while they discussed the problems of melting enough snow to handwash diapers and the advantages of owning a wig.

Joe Mekiana told me he had to take a crash course in writing Eskimo before taking a job in Chicago so he could write home to his mother who reads no English.

With my rent money, my landlord, David Mekiana, ordered 12 frozen chicken TV dinners and some beef steaks sent by air freight. I picked them up for him because they arrived while he was on a three day camping trip (at 30ºbelow zero) to tend his trap lines.

He was experimenting with wolf bait he’d gotten through an Oregon mail order outfit while his cousin was using the traditional small game. Neither caught anything and the experiment remains unresolved.

So the Inupiat find a precarious balance between two worlds. A balance that depends, unfortunately, on the whims of caribou herds and welfare agencies. Like my stove, there’s no telling when it will blow up.

There is no timber, no game and the freight rate and cost of living are higher in Anaktuvak than almost anywhere else in the United States.

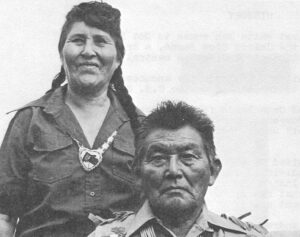

“Why, why do you live here?” I asked Simon Paneak who had been one of the first to build a permanent home.

Patiently he retraced their history. In the late 40s he had been helping a university professor study bird migration in the area and their airplane pilot found Anaktuvuk the easiest place to land supplies. Later traders encouraged settlement and a post office was established. It was the school, though, that held them.

“My family raised me up in the Brooks Range. Traveling all over,” the 71-year-old patriarch recalled. “I have never been to a school in all my life. Never learned English until I was 20. Taught myself a few words at a time by reading.

“When the school is set up we’ve got to stay where the school is. We like to have our kids learning something.”

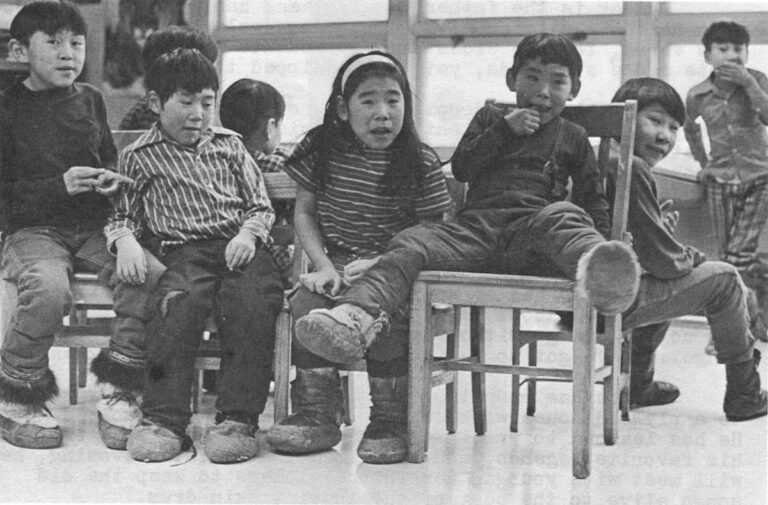

Anything New delights the Anaktuvuk youngsters. Above, Simon Paneak’s son, Harold, and granddaughter, Vickey, check out the writer’s cassette recorder which ia a newer model than Simon’s. Below, a game of musical chairs at a school party.

Paneak is the father of eight and has more grandchildren than he can easily count. He has done well by the school and vice versa, for his eldest are articulate and employable by white man’s standards, yet well equipped to live by subsistence.

Simon himself, despite a lack of formal education, is highly respected by scientists for his work in unlocking the secrets of animal and bird migration. He has long been employed by arctic research agencies and maintains a lively interest in outside work in his field.

Understandably, he reserves some nostalgia for the old life.

“We never had to worry about money, then. We traded. Nobody worried about money. A lot better, too. But right now no one can go without some money for the picture show, bingo…We’ve got to buy groceries and fuel oil is expensive.”

But he has made the transition from a caribou fur tent to a plywood house with seeming ease and considerable dignity. He has learned to write well enough to put down some of his favorite legends, and sometimes, in a winter evening, he will meet with younger men in the village to keep the old songs alive to the beat of the Inupiat skin drum.

I visited one night to listen to the music and was delighted to watch Paneak’s youngest son, Harold, age six, and his little daughter, Jenny, shyly practice the age-old dance motions in imitation of their elders. The next day they would go to Cyrus Mekiana’s and listen to his tapes of “Jesus Christ, Superstar” with the same enthusiam.

As for “why” the Inupiat settled in the Pass, I got only the vaguest answers. Maybe the airstrip…maybe it was a central meeting point. But often the answer was, “I can’t tell you.”

I wondered as they fought the cold and the children grew thinner for want of fresh meat; wondered until my last night in the Pass when the moon was as bright and full as an Inupiat face and the mountains stood close around me in the awesome beauty of its light.

Then, overwhelmed by the harsh grandeur, I stood alone on the hill by the school, not noticing the cold any more.

Who would believe that man could survive to enjoy this place? And what a feeling of strength to know you can survive it, conquer it, live with it, feast off it – or even endure it!

Received in New York on March 28, 1972

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award.winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.